chapter 5 - UniMAP Portal

advertisement

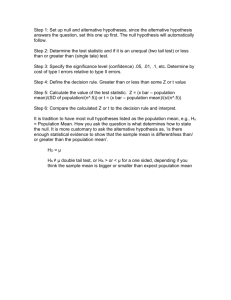

1 5.1 DATA SUMMARY AND DISPLAY Statistics ??? Meaning : Numerical facts Field or discipline of study Collection of methods for planning experiments, obtaining data and organizing, analyzing, interpreting and drawing the conclusions or making a decision. 2 BASIC TERMS IN STATISTICS Population - Entire collection of individuals which are characteristic being studied. Sample - Subset of population. Population Sample 3 Census - Survey includes every member of population. Sample survey - Collecting information from a portion of population (techniques) Element - Specific subject or object about which information collected. Variable - Characteristics which make different values. 4 Observation - Value of variable for an element. Data Set - A collection of observation on one or more variables. Table 1: Student’s Score for Business Statistic Element Name Score Mohd Amirul bin Hamdi 90 Hashimah 78 Variable Observation/ Measurement 5 TYPES OF VARIABLES Variable Quantitative Discrete (e.g, number of houses, cars accidents Qualitative Continuous (e.g., length, age, height, weight, time) e.g., gender, marital status 6 QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE VARIABLE 1) Quantitative variable A variable that can be measured numerically. Data collected on a quantitative variable are called quantitative data. There are two types of quantitative variables:i. Discrete Variable A variable whose values are countable, can assume only certain values with no intermediate values. ii. Continuous Variable A variable that can assume any numerical value over a certain interval or intervals. 2) Qualitative variable A variable that cannot assume a numerical value but can be classified into two or more nonnumeric categories. Data collected on such a variable are called qualitative data. 7 STATISTICS DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS Using tables, graphs & summary measures INFERENTIAL STATISTICS Using sample result in making decision or predict about a population. Also called inductive reasoning or inductive statistics. 8 Descriptive Statistics Consists of methods for organizing, displaying and describing data by using tables, graphs and summary measures. In general divided by two categories :- Data presentation (display) - Statistics 9 Inferential Statistics Consists of methods that use sample results to help make decisions or predictions about a population. Area statistics which are deal with decision making procedures. Example :- In order to find the salary of a college graduate, we may select 2000 recent college graduates, find the starting salaries and make decision based on the information. 10 DATA PRESENTATION A data with a lot of observations usually looks non informative - We cannot get much information with the raw data We have to summarize or organize in such a way so that we can get some information about the data. 11 DATA PRESENTATION OF QUALITATIVE DATA Tabular presentation for qualitative data is usually in the form of frequency table Frequency table- table represent the number of times the observation occurs in data A graphic display can reveal at a glance the main characteristics of a data set. Three types of graphs used to display qualitative data:- bar graph - pie chart - line chart 12 Example 5.1 Table 5.1 shows that the data of 50 UNIMAP students with their data and background. Code used : • For gender: 1 is male and 2 is female • For ethnic group: 1 is Malay, 2 is Chinese, 3 is Indian and 4 is others • Not much information can be obtained from the data 1 in the raw form. It has to be summarized so that we can get more informations. 13 If data from table 5.1 summarized into gender and ethnic group, then the frequency tables can get as below : Observation Frequency Male 28 Female 22 Total 50 Table 5.2: Frequency Table for the Gender Observation Frequency Malay 33 Chinese 9 Indian 6 Others 2 Total 50 Table 5.3: Frequency Table for the Ethnic Group 14 Bar Chart Bar chart is used to display the frequency distribution in the graphical form. It consists of two orthogonal axes and one of the axes represent the observations while the other one represents the frequency of the observations. The frequency of the observations is represented by a bar. *Bar chart is for data from Table 5.3. Figure 1: Bar Chart of the Ethnic Group 15 2.1.2 Pie Chart Pie Chart is used to display the frequency distribution. It displays the ratio of the observations. It is a circle consists of a few sectors. The sectors represent the observations while the area of the sectors represent the proportion of the frequencies of that observations. *Pie chart is for data from Table 5.2. Figure 2: The Pie Chart for the Gender 16 2.1.3 Line Chart Line chart is used to display the trend of observations. It consists of two orthoganal axes and one of the axes represent the observations while the other one represents the frequency of the observations. The frequency of the observations are joint by lines. Example : Table 2.4 below shows the number of sandpipers recorded between January 1989 till December 1989. Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec 10 7 5 10 39 7 260 316 142 11 4 9 Table 2.4 : The number of sandpipers Figure 3: The line Chart for the numbers of common Sandpipers 17 DATA PRESENTATION OF QUANTITATIVE DATA Tabular presentation of quantitative data is usually in the form of frequency distribution Frequency distribution – table that represents the frequency of the observation that fall inside some spesific classes (intervals). The are a few graph available for graphical presentation of the quantitative data. The most popular are: - Histogram - Frequency polygon - Ogive 18 FREQUENCY DISTRIBUTION When summarizing large quantities of raw data, it is often useful to distribute the data into classes. In determining the classes, there is no spesific rules but statistician suggest the number of classes are between 5 to 20 Sturges’s Rule Number of classes , c=1+3.3 log n Where n is the numbers of observations in the data set. Class width: Largest value-smallest value Number of classes Range i c i 19 Example 5.2 CGPA (Class) 2.50 - 2.75 2.75 - 3.00 3.00 - 3.25 3.25 - 3.50 3.50 - 3.75 3.75 - 4.00 Total Frequency 2 10 15 13 7 3 50 Table 5.5: The Fequency Distribution of the Students’ CGPA 20 Cumulative Frequency Distributions A cumulative frequency distribution gives the total number of values that fall below the upper boundary of each class. In cumulative frequency distribution table, each class has the same lower limit but a different upper limit. Table5.7 : Class Limit, Class Boundaries, Class Width , Cumulative Frequency Weekly Earnings (dollars) (Class Limit) Number of Employees, f Class Boundaries Class Width Cumulative Frequency 801-1000 9 800.5 – 1000.5 200 9 1001-1200 22 1000.5 – 1200.5 200 9 + 22 = 31 1201-1400 39 1200.5 – 1400.5 200 31 + 39 = 70 1401-1600 15 1400.5 – 1600.5 200 70 + 15 = 85 1601-1800 9 1600.5 – 1800.5 200 85 + 9 = 94 1801-2000 6 1800.5 – 2000.5 200 94 + 6 = 100 21 Histogram The histogram looks like the bar chart except that the horizontal axis represent the data which is quantitative in nature. There is no gap between the bars. 22 Frequency Polygon The frequency polygon looks like the line chart except that the horizontal axis represent the class mark of the data which is quantitative in nature. 23 Ogive Ogive is a line graph with the horizontal axis represent the upper limit of the class interval while the vertical axis represent the cummulative frequencies. 24 DATA SUMMARY What is statistic? Statistis is a number that describe the sample such as sample mean which describe the sample average. Type of statistic i. Measure of central tendency ii. Measure of dispersion 25 MEASURE OF CENTRAL TENDENCY There are 3 popular central tendency measures, mean, median & mode. 1) Mean The mean of a sample is the sum of the measurements divided by the number of measurements in the set. Mean is denoted by ( ) Mean = Sum of all values / Number of values Mean can be obtained as below :- - For raw data, mean is defined by, _ x x1 x2 ....... xn x , for n 1,2,..., n or x n n _ 26 For tabular/group data, mean is defined by: n x i 1 n f i xi i 1 or fi fx f Where f = class frequency; x = class mark (mid point) 27 Example The mean sample for students CGPA (raw) is x x n 160.98 3.22 50 28 Example : The mean sample for Table 5.8 Frequency, f Class Mark (Midpoint), x 2.50 - 2.75 2 2.625 5.250 2.75 - 3.00 10 2.875 28.750 CGPA (Class) fx n x 3.00 - 3.25 15 3.125 46.875 3.25 - 3.50 13 3.375 43.875 3.50 - 3.75 7 3.625 25.375 3.75 - 4.00 3 3.875 11.625 Total 50 f i xi i 1 n f 161 .75 3.235 50 i i 1 161.750 Table 5.8 29 2) Median Median is the middle value of a set of observations arranged in order of magnitude and normally is devoted by ~ x i) The median for ungrouped data. - The median depends on the number of observations in the data, . - If n is odd, then the median is the( ordered n observations. n 1 ) 2 th observation of the - If n is even, then the median is the arithmetic mean of the n n th observation and the ( 1) th observation. 2 2 30 ii) The median of grouped data / frequency of distribution. The median of frequency distribution is defined by: f F j 1 x L c 2 fj ~ where, • L = the lower class boundary of the median class; • c = the size of the median class interval; • Fj 1= the sum of frequencies of all classes lower than the median class • fj = the frequency of the median class. 31 Example for ungrouped data :The median of this data 4, 6, 3, 1, 2, 5, 7, 3 is 3.5. Proof :- Rearrange the data in order of magnitude becomes 1,2,3,3,4,5,6,7. As n=8 (even), the median is the mean of the 4th and 5th observations that is 3.5. 32 Example for grouped data :Find median for frequency distribution below Cum. CGPA (Class) Frequency, f frequency 2.50 - 2.75 2 2 2.75 - 3.00 10 12 3.00 - 3.25 15 27 f F j 1 x L c 2 fj ~ 25 12 Median , x 3.00 0.25 3.217 15 ~ 3.25 - 3.50 13 40 3.50 - 3.75 7 47 3.75 - 4.00 3 50 Total 50 33 3) Mode • The mode of a set of observations is the observation with the highest frequency and is usually denoted by ( ). Sometimes x mode can also be used to describe the qualitative data. i) Mode of ungrouped data :- Defined as the value which occurs most frequent. - The mode has the advantage in that it is easy to calculate and eliminates the effect of extreme values. - However, the mode may not exist and even if it does exit, it may not be unique. 34 *Note: If a set of data has 2 measurements with higher frequency, therefore the measurements are assumed as data mode and known as bimodal data. If a set of data has more than 2 measurements with higher frequency so the data can be assumed as no mode. ii) The mode for grouped data/frequency distribution data. - When data has been grouped in classes and a frequency curve is drawn to fit the data, the mode is the value of corresponding to the maximum point on the curve. 35 ii) The mode for grouped data/ frequency distribution data 1 x L c 1 2 where L = the lower class boundary of the modal class; c = the size of the modal class interval; 1 = the difference between the modal class frequency and the class before it; and 2 = the difference between the modal class frequency and the class after it. *Note: - The class which has the highest frequency is called the modal class. 36 Example for ungrouped data : The mode for the observations 4,6,3,1,2,5,7,3 is 3. Example for grouped data based on table : CGPA (Class) Modal Class Frequency 2.50 - 2.75 2 2.75 - 3.00 10 3.00 - 3.25 15 3.25 - 3.50 13 3.50 - 3.75 7 3.75 - 4.00 3 Total 50 1 x L c 3.179 1 2 1 5 x L c 3 . 00 0 . 25 ( ) 3.179 52 1 2 37 Measure of Dispersion The measure of dispersion/spread is the degree to which a set of data tends to spread around the average value. It shows whether data will set is focused around the mean or scattered. The common measures of dispersion are: 1) range 2) variance 3) standard deviation The standard deviation actually is the square root of the variance. The sample variance is denoted by s2 and the sample standard deviation is denoted by s. 38 39 Variance i) Variance for ungrouped data The variance of a sample (also known as mean square) for the raw (ungrouped) data is denoted by s2 and defined by: 2 ( x x ) S2 n 1 ii) Variance for grouped data The variance for the frequency distribution is defined by: fx fx n 2 S2 2 f ( x x ) fx 1 2 n 1 40 Example for ungrouped data : given income for 5 workers are : RM 1000, RM 2500, RM 2000, RM 4000, RM 3500. Find variance of this data. Solution: 1000 2500 2000 4000 3500 5 2600 Mean, x Variance, S 2 ( x x) 2 n 1 1000 2600 2500 2600 2000 2600 4000 2600 3500 2600 2 2 2 2 2 5 1 5700, 000 4 142500 41 Example for grouped data : The variance for frequency distribution in Table is: Class boundaries Frequency, f Class Mark, x 2.50 - 2.75 2.75 - 3.00 3.00 - 3.25 3.25 - 3.50 3.50 - 3.75 3.75 - 4.00 2 10 15 13 7 3 2.625 2.875 3.125 3.375 3.625 3.875 Total 50 S2 fx 2 f x n 1 n 2 fx fx2 5.250 28.750 46.875 43.875 25.375 11.625 13.781 82.656 146.484 148.078 91.984 45.047 161.750 528.031 (161.75) 2 528.031 50 0.0973 49 42 ESTIMATION Introduction The field of statistical inference consist of those methods used to make decisions or to draw conclusions about a population. These methods utilize the information contained in a sample from the population in drawing conclusions 43 ESTIMATOR VS ESTIMATE Estimator • In statistics, the method used Estimate • The value that obtained from a sample I have a sample of 5 numbers and I take the average. The estimator is taking the average of the sample. The estimator of the mean. Let say, the average = 4 the estimate. 44 CONFIDENCE INTERVAL ESTIMATES Definition : An Interval Estimate In interval estimation, an interval is constructed around the point estimate and it is stated that this interval is likely to contain the corresponding population parameter. Definition : Confidence Level and Confidence Interval Each interval is constructed with regard to a given confidence level and is called a confidence interval. The confidence level associated with a confidence interval states how much confidence we have that this interval contains the true population parameter. The confidence level is denoted by 45 CONFIDENCE INTERVAL ESTIMATES FOR POPULATION MEAN The (1 - a )100% Confidence Interval of Population Mean, m (i) x ± za s 2 n if s is known and normally distributed population æ s s ö ÷ or çç x - za < m < x + za ÷ 2 2 n nø è s if s is unknown, n large (n ³ 30) 2 n æ s s ö ÷ or çç x - za < m < x + za ÷ 2 2 n n è ø (ii) x ± za 46 s (iii) x ± tn - 1,a if s is unknown, normally distributed population 2 n and small sample size ( n < 30) æ s s ö ÷÷ or çç x - tn - 1,a < m < x + tn - 1,a 2 2 n nø è 47 EXAMPLE If a random sample of size n = 20 from a normal population with the variance s 2 = 225 has the mean x = 64.3, construct a 95% confidence interval for the population mean, m. 48 SOLUTION It is known that, n = 20, m = x = 64.3 and s = 15 For 95% CI, 95% = 100(1 – a )% 1 –a = 0.95 a = 0.05 a = 0.025 2 za = z0.025 = 1.96 2 49 æs ö ÷ Hence, 95% CI = x ± za çç ÷ n ø 2 è æ 15 ö ÷ = 64.3 ± 1.96 çç ÷ è 20 ø = 64.3 ± 6.57 = [57.73, 70.87] @ 57.73 < m < 70.87 Thus, we are 95% confident that the mean of random variable is between 57.73 and 70.87 50 Example : A publishing company has just published a new textbook. Before the company decides the price at which to sell this textbook, it wants to know the average price of all such textbooks in the market. The research department at the company took a sample of 36 comparable textbooks and collected the information on their prices. This information produced a mean price RM 70.50 for this sample. It is known that the standard deviation of the prices of all such textbooks is RM4.50. Construct a 90% confidence interval for the mean price of all such college textbooks. 51 solution It is known that, n = 36, m = x = RM70.50 and s = RM 4.50 For 90% CI, 90% = 100(1 – a )% 1 –a = 0.90 a = 0.1 a = 0.05 2 za = z0.05 = 1.65 2 52 æs ö ÷ Hence, 90% CI = x ± za çç ÷ n ø 2 è æ4.50 ö ÷ = 70.50 ± 1.65 çç ÷ 36 è ø = 70.50 ± 1.24 = [ RM 69.26, RM 71.74] Thus, we are 90% confident that the mean price of all such college textbooks is between RM69.26 and RM71.74 53 EXAMPLE Consider a survey on male students height in a certain IPTA: a random sample of 100 male students are taken. The height of the male students is normally distributed with mean 178.2 cm and variance 17.75 cm2. i) Construct a 95% CI for the mean of male students height ii) If mean of the female students height is 170.2 cm height, at 98% CI, verify whether if this can proof that the male are taller than the female students. 54 SOLUTION It is known that n 100 x 178.2 2 17.75 For 95 % CI 95% 1 100% 1 0.95 0.95 0.025 2 z z0.05 1.96 2 55 Hence 95% CI; x z n 2 17.75 178.2 1.96 100 178.2 0.83 177.37,179.03 56 ii) It is known that x 178.2 and 2 17.75 For 98 % CI 98% 1 100% 1 0.98 0.02 thus 2 0.01 z 2.33 2 Hence, 98% CI x z n 2 17.75 178.2 2.33 100 178.2 0.98 177.22,179.18 We can see that mean of female students does not lies in the interval 177.22,179.18 hence this indicate that the male students are taller than female students. 57 CONFIDENCE INTERVAL ESTIMATES FOR POPULATION PROPORTION The (1 - a )100% Confidence Interval for p for Large Samples (n ³ 30) pˆ ± za 2 pˆ (1 - pˆ ) n or pˆ - za 2 pˆ (1 - pˆ ) < p < pˆ + za 2 n pˆ (1 - pˆ ) n 58 Example According to the analysis of Women Magazine in June 2005, “Stress has become a common part of everyday life among working women in Malaysia. The demands of work, family and home place an increasing burden on average Malaysian women”. According to this poll, 40% of working women included in the survey indicated that they had a little amount of time to relax. The poll was based on a randomly selected of 1502 working women aged 30 and above. Construct a 95% confidence interval for the corresponding population proportion. 59 Solution Let p be the proportion of all working women age 30 and above, who have a limited amount of time to relax, and let pˆ be the corresponding sample proportion. From the given information, n = 1502 , pˆ = 0.40, qˆ = 1 - pˆ = 1 – 0.40 = 0.60 æ pq ö ˆˆ÷ ç Hence, 95% CI = pˆ ± za ç n ÷ 2 è ø æ 0.40(0.60) ö ÷ = 0.40 ± 1.96 çç 1502 ÷ è ø = 0.40 ± 0.02478 = [0.375, 0.425] or 37.5% to 42.5% Thus, we can state with 95% confidence that the proportion of all working women aged 30 and above who have a limited amount of time to relax is between 37.5% and 42.5%. 60 EXERCISE 61 HYPOTHESIS TESTS Hypothesis and Test Procedures A statistical test of hypothesis consist of : 1. The Null hypothesis, H 0 2. The Alternative hypothesis, H1 3. The test statistic and its p-value 4. The rejection region 5. The conclusion 62 Definition Hypothesis testing can be used to determine whether a statement about the value of a population parameter should or should not be rejected. Null hypothesis, H0 : A null hypothesis is a claim (or statement) about a population parameter that is assumed to be true. (the null hypothesis is either rejected or fails to be rejected.) Alternative hypothesis, H1 : An alternative hypothesis is a claim about a population parameter that will be true if the null hypothesis is false. 63 Test Statistic is a function of the sample data on which the decision is to be based. p-value is the probability calculated using the test statistic. The smaller the p-value, the more contradictory is the data to H 0 . DEVELOPING NULL AND ALTERNATIVE HYPOTHESIS It is not always obvious how the null and alternative hypothesis should be formulated. When formulating the null and alternative hypothesis, the nature or purpose of the test must also be taken into account. We will examine: 1) The claim or assertion leading to the test. 2) The null hypothesis to be evaluated. 3) The alternative hypothesis. 4) Whether the test will be two-tail or one-tail. 5) A visual representation of the test itself. In some cases it is easier to identify the alternative hypothesis first. In other cases the null is easier. 9.1.1 Alternative Hypothesis as a Research Hypothesis • Many applications of hypothesis testing involve an attempt to gather evidence in support of a research hypothesis. • In such cases, it is often best to begin with the alternative hypothesis and make it the conclusion that the researcher hopes to support. • The conclusion that the research hypothesis is true is made if the sample data provide sufficient evidence to show that the null hypothesis can be rejected. Example 9.1: A new drug is developed with the goal of lowering blood pressure more than the existing drug. • • Alternative Hypothesis: The new drug lowers blood pressure more than the existing drug. Null Hypothesis: The new drug does not lower blood pressure more than the existing drug. 9.1.2 Null Hypothesis as an Assumption to be Challenged • We might begin with a belief or assumption that a statement about the value of a population parameter is true. • We then using a hypothesis test to challenge the assumption and determine if there is statistical evidence to conclude that the assumption is incorrect. • In these situations, it is helpful to develop the null hypothesis first. Example 9.2 : The label on a soft drink bottle states that it contains at least 67.6 fluid ounces. • • Null Hypothesis: The label is correct. µ > 67.6 ounces. Alternative Hypothesis: The label is incorrect. µ < 67.6 ounces. Example 9.3: Average tire life is 35000 miles. • Null Hypothesis: µ = 35000 miles • Alternative Hypothesis: µ ≠ 35000 miles 9.1 DEVELOPING NULL AND ALTERNATIVE HYPOTHESIS It is not always obvious how the null and alternative hypothesis should be formulated. When formulating the null and alternative hypothesis, the nature or purpose of the test must also be taken into account. We will examine: 1) The claim or assertion leading to the test. 2) The null hypothesis to be evaluated. 3) The alternative hypothesis. 4) Whether the test will be two-tail or one-tail. 5) A visual representation of the test itself. In some cases it is easier to identify the alternative hypothesis first. In other cases the null is easier. 9.1.1 Alternative Hypothesis as a Research Hypothesis • Many applications of hypothesis testing involve an attempt to gather evidence in support of a research hypothesis. • In such cases, it is often best to begin with the alternative hypothesis and make it the conclusion that the researcher hopes to support. • The conclusion that the research hypothesis is true is made if the sample data provide sufficient evidence to show that the null hypothesis can be rejected. Example 9.1: A new drug is developed with the goal of lowering blood pressure more than the existing drug. • • Alternative Hypothesis: The new drug lowers blood pressure more than the existing drug. Null Hypothesis: The new drug does not lower blood pressure more than the existing drug. 9.1.2 Null Hypothesis as an Assumption to be Challenged • We might begin with a belief or assumption that a statement about the value of a population parameter is true. • We then using a hypothesis test to challenge the assumption and determine if there is statistical evidence to conclude that the assumption is incorrect. • In these situations, it is helpful to develop the null hypothesis first. Example 9.2 : The label on a soft drink bottle states that it contains at least 67.6 fluid ounces. • • Null Hypothesis: The label is correct. µ > 67.6 ounces. Alternative Hypothesis: The label is incorrect. µ < 67.6 ounces. Example 9.3: Average tire life is 35000 miles. • Null Hypothesis: µ = 35000 miles • Alternative Hypothesis: µ ≠ 35000 miles How to decide whether to reject or accept H 0 ? The entire set of values that the test statistic may assume is divided into two regions. One set, consisting of values that support the H1 and lead to reject H 0 , is called the rejection region. The other, consisting of values that support the H 0 is called the acceptance region. H0 always gets “=“. Tails of a Test Sign in H 0 Sign in H1 Rejection Region Two-Tailed Test = ¹ In both tail Left-Tailed Right-Tailed Test Test = or ³ = or £ < > In the left tail In the right tail 77 Population Mean, , ( known and unknown ) Null Hypothesis : H 0 : m = m0 Test Statistic : x- m Z= s n • any population, is known and n is large or • normal population, is known and n is small Z = x -s m • any population, is unknown and n is large n t = x -s m n v =n- 1 • normal population, is unknown and n is small 78 Alternative hypothesis Rejection Region H1 : m¹ m0 Z < - za 2 or Z > za 2 H1 : m > m0 Z > za H1 : m < m0 Z< - za 79 Definition: p-value The p-value is the smallest significance level at which the null hypothesis is rejected. Using the p - value approach, we reject the null hypothesis, H 0 if p - value < a for one - tailed test p - value a < for two - tailed test 2 2 and we do not reject the null hypothesis, H 0 if p - value ³ a for one - tailed test p - value a ³ for two - tailed test 2 2 80 Example The average monthly earnings for women in managerial and professional positions is RM 2400. Do men in the same positions have average monthly earnings that are higher than those for women ? A random sample of n = 40 men in managerial and professional positions showed x = RM 3600 and s = RM 400. Test the appropriate hypothesis using a = 0.01 81 Solution 1.The hypothesis to be tested are, H 0 : m £ 2400 H1 : m > 2400 2.We use normal distribution n > 30 3. Rejection Region : Z > za ; za = z0.01 = 2.33 4. Test Statistic Z= x - m 3600 - 2400 = = 18.97 s 400 n 40 Since 18.97 > 2.33, falls in the rejection region, we reject H 0 and conclude that average monthly earnings for men in managerial and professional positions are significantly higher than those for women. 82 POPULATION PROPORTION, P Null Hypothesis : Test Statistic : H 0 : p = p0 pˆ - p0 Z= p0 q0 n Alternative hypothesis Rejection Region H1 : p ¹ Z < - za p0 2 or Z > za H1 : p > p0 Z > za H1 : p < p0 Z< - za 2 83 Example When working properly, a machine that is used to make chips for calculators does not produce more than 4% defective chips. Whenever the machine produces more than 4% defective chips it needs an adjustment. To check if the machine is working properly, the quality control department at the company often takes sample of chips and inspects them to determine if the chips are good or defective. One such random sample of 200 chips taken recently from the production line contained 14 defective chips. Test at the 5% significance level whether or not the machine needs an adjustment. 84 Solution The hypothesis to be tested are , H 0 : p £ 0.04 H1 : p > 0.04 Test statistic is pˆ - p0 0.07 - 0.04 Z= = = 2.17 p0 q0 0.04(0.96) 200 n Rejection Region : Z > za ; za = z0.05 = 1.65 Since 2.17 > 1.65, falls in the rejection region, we can reject H 0 and conclude that the machine needs an adjustment. 85 REGRESSION AND CORRELATION Regression – is a statistical procedure for establishing the relationship between 2 or more variables. This is done by fitting a linear equation to the observed data. The regression line is then used by the researcher to see the trend and make prediction of values for the data. There are 2 types of relationship: Simple ( 2 variables) Multiple (more than 2 variables) THE SIMPLE LINEAR REGRESSION MODEL is an equation that describes a dependent variable (Y) in terms of an independent variable (X) plus random error Y = b 0 + b1 X + e where, 0 1 = intercept of the line with the Y-axis = random error = slope of the line Random error, is the difference of data point from the deterministic value. This regression line is estimated from the data collected by fitting a straight line to the data set and getting the equation of the straight line, Ù Ù Ù Y = b 0+ b1 X LEAST SQUARES METHOD • The least squares method is commonly used to determine values for 0 and 1 that ensure a best fit for the estimated regression line to the sample data points • The straight line fitted to the data set is the line: Ù Ù Ù y = b 0+ b1 x y is the estimated or predicted value of y for a given value of x. In other words, the predicted value of the dependent variable y for a given independent variable x can simply be obtain by substituting the given value of x. We can find the least squares estimators 0 and formula Ù b1 = Ù 1 by using the Sxy Sxx Ù b 0 = y - b1 x where 1 n x xi n i 1 1 n y yi n i 1 æ n öæ n ö çå xi ÷çå yi ÷ n S xy = å xi yi - è i =1 øè i =1 ø n i =1 æ n ö2 çå xi ÷ n 2 S xx = å xi - è i =1 ø n i =1 n S yy = å i =1 æ n ö2 çå yi ÷ 2 yi - è i =1 ø n 89 EXAMPLE Suppose we take a sample of seven household from a low moderate income neighborhood and collect information on their income and food expenditures for the past month. The information obtained (in hundreds of Ringgit Malaysia) is given below Income Food expenditures 35 9 49 15 21 7 39 11 15 5 28 8 25 9 Find the least squares regression line of food expenditure (Y) on income (X) 90 SOLUTION Income Food Expenditure x 35 49 21 39 15 28 25 y 9 15 7 11 5 8 9 xy 315 735 147 429 75 224 225 x2 1225 2401 441 1521 225 784 625 y2 81 225 49 121 25 64 81 ∑ x = 212 ∑ y = 64 ∑ xy = 2150 ∑ x2 = 7222 ∑ y2 = 646 Compute x, y, x and y 91 x 212 x y 64 x 212 =30.2857 n 7 compute xy and xy 2150 x x 2 y y 64 9.1429 n 7 2 7222 compute S xy and S xx n n xi yi n 212 64 211.7143 S xy xi yi i 1 i 1 2150 n 7 i 1 2 n 2 xi n 212 S xx xi 2 i 1 7222 801.4286 n 7 i 1 compute 0 and 1 1 S xy S xx 211.7143 0.2642 801.4286 0 y 1 x 9.1429 0.2642 30.2587 1.1414 Thus our regression model is y 1.1414 0.2642x 92 CORRELATION (R) Correlation measures the strength of a linear relationship between the two variables. Also known as Pearson’s product moment coefficient of correlation. The symbol for the sample coefficient of correlation is r Formula : r = S xy S xx .S yy Properties of r : - 1£ r £ 1 Values of r close to 1 implies there is a strong positive linear relationship between x and y. Values of r close to -1 implies there is a strong negative linear relationship between x and y. Values of r close to O implies little or no linear relationship between x and y. EXAMPLE Refer example before. Calculate the value of r and interpret its meaning. Solution From example before we know that S xy 211.7143 and S xx 801.4286 compute 2 n 2 yi n 64 S yy yi 2 i 1 646 60.8571 n 7 i 1 S xy 211.7143 r 0.9587 S xx S yy 801.4286 60.8571 Since the r value close to 1, implies that there is strong positive linear relationship between income (x) and food expenditure (y). 95