Managers in the familiar_20130326

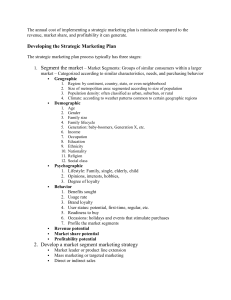

advertisement