Chapter 1: An Introduction to Corporate Finance

INTRODUCTION TO

CORPORATE FINANCE

SECOND EDITION

Lawrence Booth & W. Sean Cleary

Prepared by Ken Hartviksen & Jared Laneus

Chapter 7

Equity Valuation

7.1 Equity Securities

7.2 Preferred Share Valuation

7.3 Common Share Valuation: The Dividend Discount

Model (DDM)

7.4 Using Multiples to Value Shares

7.5 Additional Multiples or Relative Value Ratios

7.6 A Simple Application: Tim Hortons Inc.

Appendix 7A: A Short Primer on Bubbles

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

2

Learning Objectives

7.1 Identify the basic characteristics of equity securities

(i.e., preferred shares and common shares) and describe the general framework for valuing equity securities.

7.2 Explain how to value preferred shares.

7.3 Explain how to value common shares using the dividend discount model.

7.4 Explain how to value common shares using the priceearnings (P/E) ratio.

7.5 Explain how to value common shares using additional relative value ratios.

7.6 Apply the principles of fundamental valuation and relative valuation.

7.7 Explain how speculative price bubbles occur.

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

3

Equity Securities

• Equity securities represent ownership claims on businesses with residual claims to earnings after tax and to assets upon

dissolution, and the prospect for participation in the growth and profitability of the business

• Equity securities can be valued based on approaches using the present value of expected future dividends (dividend discount models) or relative valuation models

• Equity securities include preferred and common shares, and may pay dividends from after-tax earnings at the discretion of the board of directors

• Unlike bonds, which are most often finite in life, equities like corporations are assumed to have an infinite life so long as the underlying corporation is a going concern

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

4

Common Shares

•

According to the Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA) corporations must have at least one share class with the following rights:

• Rights to residual earnings after-tax and all legal obligations to other claimants have been satisfied

• Rights to residual assets upon dissolution or liquidation

• Rights to exert control over the corporation by voting to elect a board of directors, accept financial statements, appoint auditors and approve major issues such as takeover bids and corporate restructurings

•

Equities that have all three of these characteristics are usually called

common shares

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

5

Preferred Shares

• Preferred shares have priority over common shares and represent a different share class

• Characteristics of preferred shares:

• Pay a fixed, annual or quarterly dividend which is not legally enforceable by shareholder if not declared by the board of directors

• Have priority over the common share class to dividends and assets upon dissolution

• Have no voting rights, except if dividends are in arrears

• Have no maturity date

• Often have a cumulative feature, where dividends in arrears must be paid in full before common shareholders can receive a dividend

• Often called a fixed income investment because the regular annual dividend is fixed (or set) at the time the shares are originally issued and does not change after the shares are issued

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

6

Equity Security Valuation Using DCF

• The discount rate k, to be used when equities are valued using discount cash flow methods should reflect the current level of interest rates, based on the risk-free rate, plus a risk premium that represents the riskiness of the investment, as in Equation 7-1: k

RF

Risk Premium k

Real Return

Expected Inflation Rate

Risk Premium

Required

Return (%)

Required return on Equity

Security (M)

Risk Premium

RF

Risk of Equity

Security M

Real Return

Expected Inflation Rate

Risk

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

7

Preferred Share Valuation

• Straight preferred shares can be viewed as perpetuities because of the perpetual, constant dollar dividend they offer, as in Figure 7-1

• Equation 7-2 shows that the price of a preferred share is the annual divided amount divided by the investor’s required rate of return.

• Example: What is the price of a $100 par-value preferred share that pays a 7% dividend if the required return is 10%?

• The annual divided is the par value multiplied by the dividend rate:

$100 × 7% = $7

P ps

D p k p

$ 7 .

00

0 .

10

$ 70 .

00

• Like bonds, when the required return equals the dividend rate, the price will equal the par value

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

8

Preferred Share Valuation

• Equation 7-2 can be re-arranged into Equation 7-3 to determine the investor’s required rate of return

• For market-traded preferred shares, the stock price and annual dividend will be observable, but the investor’s required return is unknown

• Example: What is the implied required return on a $100 par-value preferred share that pays a 7% dividend if price is $57.25?

• The annual divided is the par value multiplied by the dividend rate:

$100 × 7% = $7 k p

D

P ps p

$ 7 .

00

$ 57 .

25

12 .

22 %

• Since the preferreds were trading for less than par ($57.25 < $100.00), it makes sense that the required return would exceed the dividend rate

(12.22% > 7.00%)

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

9

Common Share Valuation:

The Dividend Discount Model (DDM)

• All discounted cash flow models estimate the current economic value of any security as the sum of the discounted, or present, value of all promised future cash flows

• The current value is therefore a function of the timing, magnitude and riskiness of future cash flows

• In the case of common stock, the cash flows of a going-concern are expected to continue perpetually, and cash flow risk is taken into consideration through the investor’s required return (discount rate)

• The amount and timing of future dividends is uncertain because dividends, unlike interest payments, are not a fixed obligation of the firm. Instead, dividends are declared at the discretion of the board of directions. Although share prices can fall substantially if dividends are cut or eliminated, there is no guarantee or requirement for boards always to approve a dividend.

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

10

Common Share Valuation:

The Dividend Discount Model (DDM)

• In the dividend discount model (DDM) the intrinsic value of a share is equal to the sum of the present value of all future dividends, as in Equation 7-4:

P

0

1

D

1

k

C

( 1

D k

2

C

)

2

...

D n

( 1

P n k

C

) n where:

• P

0

= the estimated share price today

• D

1

• P n

= the expected dividend at the end of year 1

= the expected share price after n years

• k

C

= the required return on the common shares

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

11

Common Share Valuation:

The Dividend Discount Model (DDM)

• If, instead of holding the stock for n years we hold the stock forever, Equation 7-4 becomes Equation 7-5:

P

0

1

D

1

k

C

( 1

D

2 k

C

)

2

...

( 1

D

k

C

)

t

1

( 1

D t k

C

) t

• The dividend discount model is a type of fundamental analysis because the estimate of inherent worth the stock is based on its economic fundamentals

• Once you estimate inherent worth, you can compare your estimate with the actual market price of the stock to determine whether it is under, over or fairly priced by the market relative to your understanding of the stock’s fundamentals

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

12

Common Share Valuation:

The Constant Growth DDM

• Equations 7-6 and 7-7 shows how to value a share when dividends grow at a constant rate of growth g forever:

P

0

D

0

(

1

1

k

C g )

D

0

(

( 1

1

k

C g )

2

) 2

...

D

0

(

( 1

1

k

C g )

)

D

0

( 1

k

C

g g )

k

C

D

1

g

• Or, more simply:

P

0

1 k

D

C g

• This relationship holds when k

C

> g, otherwise the answer is negative and the answer is uninformative

• Only future estimated cash flows and estimated growth in these cash flows are relevant

• The relationship holds only when growth in dividends is expected to occur at the same constant rate indefinitely

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

13

Common Share Valuation:

The Constant Growth DDM

• We can re-arrange Equation 7-7 into Equation 7-8 to determine the investor’s required rate of return: k

C

D

1

g

Dividend Yield

Capital Gains Yield

P

0

• If the firm has no profitable growth opportunities (g = 0) and pays out all of its earnings as dividends (D = EPS), the DDM is (Equation 7-9):

P

0

EPS

1 k

C

• If the firm does have potential growth opportunities, Equation 7-10 states that the price is:

P

0

EPS

1

PVGO k

C

Value of No Growth Component

PV of Growth Opportunit ies

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

14

Common Share Valuation:

The Constant Growth DDM

• The constant growth dividend discount model predicts that stock prices will increase if :

• Dividends are increased

• The growth rate increases

P

0

1 k

D

C g

• The investor’s required return decreases

• The constant growth dividend discount model predicts that stock prices will decrease if:

• Dividends are decreased

• The growth rate decreases

• The investor’s required return increases

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

15

Common Share Valuation:

The Constant Growth DDM

• The sustainable growth rate can be used as the constant growth rate, and estimated as (Equation 7-11):

• g = b × ROE

• g = earnings retention ratio × return on common equity

• Equation 7-12 shows that, using a DuPont analysis, ROE can be decomposed as:

• ROE = net profit margin × turnover ratio × leverage ratio

• ROE = (net income / sales) × (sales / assets) × (assets / equity)

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

16

Common Share Valuation:

The Constant Growth DDM

• Therefore, managers can increase the firm’s value by increasing its sustainable growth rate

• And, managers can increase the firm’s sustainable growth rate by:

• Increasing the net profit margin

• Increasing turnover

• Adding leverage (as long as this doesn’t cause k

C to rise)

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

17

Common Share Valuation:

The Multiple Stage Growth DDM

• Many firms have earnings that grow at different, non-constant rates over time

• Figure 7-2 shows one example of a multiple-stage growth DDM, the two-stage DDM, where there is an immediate high-growth phase followed by a lower, more normal, long-term growth phase that continues in perpetuity

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

18

Common Share Valuation:

The Multiple Stage Growth DDM

• We can use Equation 7-13 to value multiple stage growth in dividends:

P

0

1

D

1

k

C

( 1

D

2 k

C

)

2

...

(

D t

1

k

C

P t

) t where : P t

k

C

D t

g

• Example: A company is expected to pay a $1 dividend at the end of this year, a $1.50 dividend at the end of year 2, and a $2 dividend at the end of year 3. Dividends will grow at a constant rate of 4% per year thereafter. Determine the market price of this company’s common shares if the required return is 11%.

P

0

1

D

1

k

C where : P

3

( 1

D

2 k

C

)

2 k

C

D

4

g

(

D

3

1

k

C

P

D

3

( 1

k

C

g g )

3

)

3

1

1

.

.

00

11

0 .

11

0 .

1

1

2 .

00 ( 1 .

04 )

.

04

.

50

11

2

2 .

00

1

$ 29 .

7143

29

.

11

3

.

7143

$ 25 .

31

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

19

Common Share Valuation:

DDM Limitations

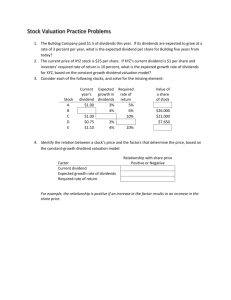

• The dividend discount model’s estimate of prices is highly sensitive to changes in forecast growth and the investor’s required rate of return

• The DDM is also unable to value firms that do not pay dividends

• Discounted free cash flow models can be used for firms that do no pay dividends; and, indeed, this is a more popular approach than the

DDM model (see Table 7-1, next slide)

• In fact, the DDM is best suited to firms that pay dividends based on a stable dividend payout history and which are likely to maintain that practice into the future because they are growing at a steady and sustainable rate

• Therefore, this model works well for large corporations in mature industries, such as banks and utility companies

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

20

Common Share Valuation:

Which Methods Are Used in Practice?

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

21

Using Multiples to Value Shares

• Relative valuation approaches estimate the value of common shares by comparing market prices of similar companies relative to some financial variables:

• Earnings or net income

• Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization

(EBITDA)

• Cash flow

• Book value

• Sales or revenue

• The hardest part of relative valuation is to find the best set or ratios for comparison and to use the most relevant, appropriate accounting data, making adjustments as necessary to account for both material economic differences and accounting policy differences between companies

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

22

The Price-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

• The price-earnings (P/E) ratio , or the earnings multiple, tells you how many times projected annual earnings per share the current share price is

• Equation 7-13:

P

0

Estimated

EPS

1

P

/

E

ratio

EPS

1

P

0

EPS

1

• Example: If you buy a company trading at 10 times projected earnings, it may take 10 years, assuming constant earnings, to recover your investment. Contrast this with a company trading at

100 times earnings, where it may take 100 years of comparable earnings to recover your investment. Note that these analyses ignore time value.

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

23

The Price-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

• Figure 7-3 shows the history of the P/E ratio of the S&P/TSX based on trailing multiples

• Volatility in aggregate P/E is driven by volatility of earnings:

• When earnings fall dramatically, as in a recession, P/E ratios can become large if earnings drop faster than stock prices

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

24

The Price-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

• Estimate EPS using historical earnings data, projected trends, and analyst estimates

• Estimate the justifiable P/E ratio using industry averages, a range of possible P/E values, or subjectively adjusted industry averages based on risk assessment

• Obtain corroborating estimates based on economic, industry, and company fundaments, and/or relate P/E to the fundamentals in the dividend discount model

• Equation 7-15 shows that the expected dividend payout ratio (D

1 the required rate of return (k

C

/ EPS

1

),

) and the expected dividend growth rate (g) affect the justified P/E ratio:

• All else being equal:

P

0

EPS

1

D k

1

C

/ EPS

1

g

• the higher the expected payout ratio, the higher the P/E

• the higher the expected growth rate, the higher the P/E

• the higher the required return, the lower the P/E

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

25

The Price-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

Limitations of P/E Ratios

• P/E ratios are uninformative when companies have negative (or very small) earnings

• Volatility in earnings causes volatility in P/Es throughout the business cycle

• Analysts normally smooth or normalize earnings estimates when forecasting to avoid these limitations, and use scenario analysis to develop a range of potential values for the stock

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

26

Additional Multiples or Relative Value Ratios

• Additional relative value ratios include:

• Market to book (M/B)

• Price to sales (P/S)

• Price to cash flow (P/CF)

• Market to EBIT (M/EBIT)

• Market to EBITDA (M/EBITDA)

• Note: EBIT = earnings before interest and taxes and EBITDA = earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization

• Use of comparative multiples is a popular approach to valuing stock

• Despite the apparent simplicity of generating the ratios, considerable effort goes into analyzing the comparability of accounting data, volatility and other issues affecting the usefulness of relative valuation

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

27

Market-to-Book (M/B) Ratio

• Market-to-book ratio (M/B) = Market price per share/Book value per share

• Multiply the justifiable M/B ratio by the firm’s book value per share to estimate intrinsic value per share

• The M/B ratio fell out of favour in the 1980s and 1990s because high rates of inflation distorted book values

• Advantages:

• Book values provide a relatively stable, intuitive measure of value relative to market values

• Eliminates the problems associated with P/E multiples because book values are rarely negatives and less volatile

• Disadvantages:

• Book values can be sensitive to differences in accounting standards

• Book values may be uninformative for companies with few fixed assets or lots of off balance sheet financing

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

28

Price-to-Sales (P/S) Ratio

• Price-to-sales ratio (P/S) = Price per share / Revenue per share

• Multiply the justifiable P/S ratio by the firm’s sales per share to estimate intrinsic value per share

• Advantages:

• Sales are relatively insensitive to accounting policy changes and are never negative

• Sales are not as volatile as earnings

• Sales provide useful information about corporate decisions such as product pricing

• Disadvantages:

• Sales do not provide any information about expenses and profit margins, which are key determinants of corporate performance

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

29

Price-to-Cash Flow (P/CF) Ratio

• Price-to-cash flow (P/CF) = Price per share / Cash flow per share

• Cash flow per share can be estimated as net income plus depreciation, amortization and deferred taxes

• Multiply the justifiable P/CF ratio by the firm’s cash flow per share to estimate intrinsic value per share

• Advantages:

• Reduces accounting concerns about earnings measurement

• Disadvantages:

• Can flow can be negative

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

30

EBIT and EBITDA Ratios

• Multiply the justifiable ratio times the firm’s forecast EBIT or

EBITDA per share to estimate intrinsic value

• Market value to EBIT or EBITDA ratios : Use the market value of both debt and equity since EBIT and EBITDA represent income available to satisfy the claims of both debt and equity holders

• Advantages:

• Using EBIT and EBITDA instead of net income reduces volatility caused by EPS

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

31

A Simple Application: Tim Hortons Inc.

Dividend Discount Models

• Suppose Tim Hortons’ discount rate is 6.3% (see Chapter 9 for how this is determined). 2009 analyst consensus EPS is $1.80 and the 2008 dividend payout ratio is 23.22%. If Tim Hortons’ dividends and earnings grow at 5% to infinity, then the price of the shares should be:

P

$ 1 .

80 ( 0 .

2322 )

0 .

063

0 .

05

$ 32 .

15

• If Tim Hortons’ return on equity is 24.96%, then the sustainable growth rate is: g = (1 – payout ratio) × ROE = (1 – 0.2322) × 0.2496 = 19.16%

• So, Tim Hortons’ could grow faster than 5%, at least in the short term.

• Suppose growth is 11% for four years after 2009, with 5% growth to infinity thereafter. This gives a share price of $39.94. (Try the calculation yourself for practice.)

• If Tim Hortons’ stock price were only $30, our calculations suggest the shares are undervalued.

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

32

A Simple Application: Tim Hortons Inc.

Relative Valuation Models

• If Tim Hortons’ discount rate is 6.3%, 2009 analyst consensus EPS is $1.80 , the 2008 dividend payout ratio is 23.22% and Tim Hortons’ dividends and earnings grow at 5% to infinity, we can use Equation 7-15 to value Tim

Hortons shares.

P

E

0 .

2322

0 .

063

0 .

05

17 .

86

P

17 .

86 E

17 .

86 ($ 1 .

80 )

$ 32 .

15

• Alternatively, we could use Tim Hortons’ historical averages, industry averages or averages of other comparable companies.

• Example: If Tim Hortons’ average P/E ratio is 23.52 between 2007 and 2008, and its 2008 EPS was $1.55, then its price would be $36.45

• Example: The average P/E for McDonald’s and Starbucks was 25.57. With

2008 EPS of $1.55, Tim Hortons’ price would then be $39.64.

• If Tim Hortons’ stock price was only $30, our calculations again suggest the shares are undervalued.

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

33

A Short Primer on Bubbles

• Bubbles are significant and generally unwarranted increases in asset prices that lead to unsustainably high price levels

• Notable bubbles through history:

• Dutch Tulip Bulb Bubble (1636)

• South Sea Bubble and Mississippi Bubble (1720)

• U.S. Stock Price Bubble (1927 to 1929)

• Japanese Real Estate and Stock Price Bubble (1985 to 1989)

• Internet Stock Bubble (1995 to 2000)

• U.S. Real Estate Bubble and Sub-Prime Crisis (2000s)

• In bubbles investors exhibit herd-like behaviour, overconfidence and fear of regret if they fail to participate in the bubble

• During bubbles investors also tend to believe that “old guidelines” for valuation and risk-management no longer matter. But, they do

matter, and bubbles are often followed by market corrections or crashes

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

34

Copyright

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd. All rights reserved. Reproduction or translation of this work beyond that permitted by Access Copyright (the Canadian copyright licensing agency) is unlawful. Requests for further information should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons

Canada, Ltd. The purchaser may make back-up copies for his or her own use only and not for distribution or resale. The author and the publisher assume no responsibility for errors, omissions, or damages caused by the use of these files or programs or from the use of the information contained herein.

Booth/Cleary Introduction to Corporate Finance, Second Edition

35