Utopias in American History By: Jyotsna Sreenivasan Introduction

advertisement

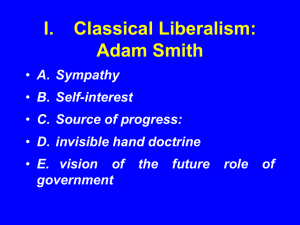

Utopias in American History By: Jyotsna Sreenivasan Introduction What Is a Utopian Community? Utopia is a word coined by Thomas More, a 16th-century English writer, from two Greek words. It literally means “nowhere.” More imagined and wrote about an ideal country where citizens lived in harmony and prosperity. He called his ideal country “Utopia.” Today, a “utopian community” refers to a group of people trying to live according to their highest values. Utopian communities are communities in which unrelated people live together by choice and that are designed to foster values that the members think are important, such as spirituality, cooperation, economic equality, or a simple lifestyle. These communities are formed to offer what are seen as better alternatives, a better way of life, than what can be found in the larger society. These kinds of communities are also called communes, collective settlements, or intentional communities. Members of utopian communities generally share resources and labor. In other words, the members of the community live together, work together, and share their money, food, and other belongings, to a greater or lesser degree. Some communities go as far as sharing things like child care, with the entire community involved in caring for the children. In other communities, families have their own houses and their own belongings, but they may share strict spiritual beliefs, rules about living, and some work and property. All societies—including the one you live in now—are designed with some values and foster some values. But utopian communities are very aware of how their values differ from those of the larger world. They are proactive in promoting their own values and trying to create structures that foster them. The Beginnings of Utopian Communal Life Communal living may have begun with human evolution. Historian Donald Pitzer points out that early humans banded into kinship groups and tribes. These cooperative groups helped individual members to survive and thrive (1997, 3). As human society developed, so too did the urge for some groups to withdraw from the mainstream of society and create their own idealistic, utopian communities. The earliest utopian communes that scholars are aware of may have been self-sufficient Taoist communes in China in the fifth century BCE. In the Western world, the earliest utopian communities that we have evidence of are the Jewish Essenes, who attempted to create their own communities in the face of the imposition of Greek values upon their culture. About 4,000 Essenes lived communally in Palestine (now Israel) from 150 BCE to 68 CE. The early Christians also lived communally, according to the New Testament Book of Acts (Zablocki 1980, 25–26). Throughout most of history, the vast majority of utopian communities had a religious or spiritual basis. In fact, some of the most widespread and enduring types of utopian communities are monasteries and nunneries, where men and women live separately and carry out religious duties. We will not discuss these in this book, but will concentrate on communities that include women, men, and children. Why Study Utopias in American History? You might ask, Why study communal utopias in America? After all, America is the land of individualism, of personal freedom. The “American Dream” is the idea that any individual, with hard work and determination, can achieve success and prosperity. Communal sharing has nothing to do with American values—does it? Yet the freedom experienced by those who live in the United States has also led in a different direction. A 1998 article in the Washington Post about a modern socialist commune, Twin Oaks, is entitled “The Other American Dream.” And in many ways starting a utopian community is in fact an alternative American dream. Utopian communities among the Europeans in the New World began soon after the Pilgrims arrived. Starting in the 17th century, persecuted religious sects fled Europe for North America, and some of them set themselves up communally in the land that would become the United States. The first communal society in the New World is believed to have been the Valley of the Swans, an extraordinary group founded in Delaware in 1663, which espoused freedom of thought and religion, and separation of church and state. Unfortunately this fledgling community was destroyed by the English in 1664. An Israeli scholar who has studied American communes, Yaacov Oved, points out that “since 1735 there has been a continuous and unbroken existence of communes in the United States. There is no equivalent in any of the other countries of the modern world” (1988, 3). Oved gives several reasons for this phenomenon, including the availability of land (albeit land taken from the American Indians) and a tradition of liberty and religious tolerance. Paul Boyer suggests that “American society, with its comparative lack of hierarchy, freedom from the weight of tradition, and openness to social innovation, has historically provided a particularly congenial environment in which communal experimentation could flourish” (1997, xi). A number of religious groups, persecuted for their beliefs in Europe, fled to the New World and later the United States in order to live in peace, and some of them formed communal societies. Such groups include the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness, the Amish, the Shakers, the Harmony Society, the Zoar Society, the Amana Colonies, and Bishop Hill. In addition to religious tolerance, the U.S. political system was inspiring to others. According to Oved, the United States itself was designed to “set an example of a perfect society.... The United States, being independent of the old system, would carry the message of a social experiment for all of humanity. It would be the place where those social and political ideals, which European thinkers had cogitated but which could not be carried out there, might materialize” (1988, 5). Robert Owen (founder of New Harmony), Etienne Cabet (founder of the Icarian movement), Thomas Hughes (founder of Rugby), and other European social reformers looked to the United States as a place where their ideal society might take root and flourish. According to Arthur Bestor, “of all the freedoms for which America stood, none was more significant for history than the freedom to experiment with new practices and new institutions” (1950, 1). Bestor sees communal living as one of four ways of reforming society. The other three are the individual thinker who influences others; revolution; and gradualistic reform movements targeting certain conditions (such as alcoholism or poverty). “Communitarianism does not correspond to any of these [other three]. It is collectivistic not individualistic, it is resolutely opposed to revolution, and it is impatient with gradualism” (1950, 3–4). Another reason to study utopian communities, besides their significance in American history, is that such communities can give us insights into new ways of solving problems. According to sociologist Rosabeth Moss Kanter: Social science has rarely had “laboratories” of the scale and scope of utopian communities. Contemporary social systems, from schools to families to businesses, are founded on many assumptions about human needs and the requirements of social life, which communities challenge. Confronting the “givens” of American life with data from communal orders poses interesting questions. For example, can commitment and collective feeling replace individual, material rewards as a source of motivation? Is the nuclear family in its present, isolated form a necessary ingredient in emotional satisfaction? Could productive work be reorganized, perhaps in terms of rotating shared jobs rather than individual careers? . . . As America’s problems grow, so does the need for conceiving new ways of being and doing, and hence for a return of the utopian imagination (1972, viii). Overview of Utopian Communities in America Over the history of the United States, there have been a number of “peaks” of commune building—times when more communal societies started. The first of these peaks occurred in the late 1700s (when the Shakers were newly active). The first part of the 1800s saw several waves of Christian and socialist community building, including the Christian communal societies of Harmony, Zoar, Bishop Hill, and Oneida; the socialist communities New Harmony, the Icarian movement, and the Fourierist phalanxes; and the antislavery communities. Toward the end of the 1800s, the Christian Hutterites arrived in the United States, and have since grown into one of the largest utopian communal movements in the country. The end of the 1800s was also an active period for communities based on socialism and other new economic and political theories: the socialist Kaweah Cooperative Commonwealth began, as well as Fairhope, based on the single-tax theory, and Home, an anarchist community. The Theosophical Point Loma also started at this time. The years of the Great Depression, the 1930s, saw a flurry of cooperative and communal activity sponsored by the U.S. government: the New Deal communities, which involved about 50,000 people. Also starting at this time was the Catholic Worker Movement, an anarchist and socialist movement to help the needy. The Peace Mission Movement experienced incredible growth during the Great Depression. During the late 1960s and 1970s, the hippie-inspired communes took off, including communities based on Eastern religions and the “Jesus Freak” communities (Zablocki 1980, 31–32). The latest major American utopian communal movement, the cohousing movement, which began in 1991 in the United States, had grown to over 2,000 households as of 2007 and is poised for even greater growth. Kanter divides utopian communities into three categories: those with a desire to live according to spiritual values; those that hoped to reform society through political or economic means; and those that wanted to promote personal growth by connecting people on a deeper level. Kanter suggests that these three categories correspond in a general way with three historical periods of American communities. Spiritual communities predominated until 1845; communities based on socialism, anarchism, or other political or economic ideals flourished from 1820 to 1930 or so; and communities that promoted personal growth became important after World War II, and especially in the 1960s. However, she points out that communities can belong to more than one category. For example, Oneida was a Christian community, yet was also interested in socialism and personal growth (1972, 8–9). Some utopian communities of the past have left a lasting impression, even after the community itself has folded. The Moravian movement founded the towns of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The Shakers pioneered a unique, simple style of furniture that is still in high demand today. They are also credited with inventing many tools still in use; for example, the flat broom, clothespin, and circular saw. The members of the many short-lived Fourierist communities were involved with starting the cooperative movement in the United States, as were members of the Jewish agricultural communities. Out of the Oneida community grew one of the world’s largest manufacturers of silverware. A business started by Amana members has become one of the world’s largest manufacturers of refrigerators. Synanon pioneered a self-help approach to treating drug addicts. There are many utopian or intentional communities around the world today. The Fellowship for Intentional Community estimates that there are several thousand such communities, including the more than 900 listed in its 2007 Communities Directory. Many of these communities are small or in the formative stages. In this book, we examine only a small number of the many utopian communities that have formed and dissolved over the history of the United States. This book concentrates on communities that are (or have been) exceptionally large, long-lived, influential, or unique. I have tried to cover the important communities in the history of the United States through the early years of the 21st century, but I know I may have overlooked communities that others might consider important. Why Form a Utopian Community? Some communities were formed in order to separate their members from the outside world, which was seen as sinful. These communities did not want to influence or interact with the outside world—they simply wanted to be left alone to live their own separate lifestyle. Often, these communities had to flee persecution in Europe. The Amana Colonies, the Amish, the Harmony Society, the Hutterites, the Zoar Society, the Bruderhof, and the Love Family are examples of such separatist communities. Other religious communities, while believing the outside world to be sinful, interacted extensively with outsiders. They wanted to influence outsiders to join with them and be “saved.” Such communities included the Davidian and Branch Davidian movements and the House of David movement. The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (Hare Krishnas) also believed the outside world to be sinful, yet actively sought converts in the outside world: they believed that chanting the Hare Krishna mantra (prayer) would lead to spiritual awakening, peace, and unity. Some communities—particularly socialist communities—were formed in order to influence and transform the outside world into adopting the lifestyle and values of the communal experiment. These communities hoped that their shining example would influence others to form similar communities. New Harmony, the first secular, socialist community in the United States, founded in 1825, was meant to be a model for a plan to be adopted all over the industrialized world. The Icarians, a socialist community of French immigrants founded in 1848, hoped to set up a huge community with as many as a million people, which would be the envy of the rest of the world. The Llano colonies, socialist communities founded in 1914, thought they had a solution to the widespread poverty of the Great Depression. In 1933, the Llano leader worked with a Texas senator to introduce national legislation that would have replicated the Llano colony around the country as a way to solve unemployment. Some nonsocialist communities also hoped to transform the outside world. The founder of the Brotherhood of the New Life (1861–1900), Thomas Lake Harris, wrote that he and his followers believed their community to be “a germ of the Kingdom of Heaven, dropped from upper space and implanted in the bosom of the earthly humanity—in fine, the seed of a new order; the initial point for a loftier and sweeter evolution of man” (Hinds 1961, 143). The Fairhope community, founded in 1894, hoped that its example of single-tax economics would convince the rest of the country to adopt the single tax. The leader of Point Loma, a Theosophical community founded in 1897, hoped to set up a series of “Raja Yoga” schools around the world, modeled on the one at Point Loma. The Ananda Colonies, founded in 1968, hope to “usher in a new spiritual renaissance” around the world, according to their Web site. Although no single community movement succeeded in transforming the outside world to the extent that they envisioned, together they offer a real alternative to mainstream American society, based as it is on private ownership, nuclear families, and materialism. The communities showed Americans (who were often intensely curious about communal experiments) that there were other ways of living a happy, productive life. Why Live in a Utopian Community? Why do people choose to leave their familiar ways of life and join with other people to follow unfamiliar rules and live in a way that might be considered unusual? People join for practical as well as idealistic reasons. During times of economic hardship, people might join a communal society if they believe that it will help them provide for their families, or provide a way out of an intolerable living situation. People also join a community because they want to live with others who share their religious beliefs, or their beliefs in other values such as economic equality. They might join because they want to become part of a small, close-knit community, or to live with a friend or family member who is already part of that community (Zablocki 1980, 105). The Shakers, a Christian sect that split from the Quakers, are one of the most famous of the American utopian communities. Thousands of people joined the Shakers from the time they landed in the American colonies in 1774 through the early 1900s, when they became largely defunct. One estimate suggests that at least 20,000 people lived part of their lives as a Shaker (Brewer 1997, 37). Why were people attracted to this religion that required them to give up marriage, childbearing, and personal property? William Kephart suggests that some of the reasons may have been practical. In the 18th and 19th centuries, divorce was illegal or, at best, difficult to obtain. A woman or man in an unhappy marriage could join the Shakers and be separated from her or his spouse, since the women and men lived separately (1978). Another practical reason for joining may have been economic. A person who was having trouble making enough money—such as a widow with young children—could join the Shakers and receive adequate food, clothing, and child care in exchange for working within the community. During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was no life insurance and jobs for women were limited. However, not everyone who joined the Shakers came from an unhappy marriage, or was having trouble making ends meet. Many people were truly attracted to the Shaker religion—the combination of order and simplicity in daily life and the frenzied dancing and singing on Sundays. Some people believed that Mother Ann (the Shakers’ first leader) was indeed the female incarnation of Christ (Kephart 1978 164– 166). In times of economic trouble, there is great advantage to pooling resources and living communally. The Zoar Society, a Christian sect that fled Germany, originally adopted communal living, because, upon arriving in the United States, it realized that some of its members were too old or sick to farm their own private land. A member of the Zoar Society describes the benefits of communal living: The advantages are many and great. All distinctions of rich and poor are abolished. The members have no care except for their own spiritual culture. Communism provides for the sick, the weak, the unfortunate, all alike, which makes their life comparatively easy and pleasant. In case of great loss by fire or flood or other cause, the burden that would be ruinous to one is easily borne by the many. Charity and genuine love to one another, which are the foundations of true Christianity, can be more readily cultivated and practiced in Communism than in common, isolated society. Finally, a Community is the best place in which to get rid of selfishness, willfulness, and bad habits and vices generally; for we are subject to the constant surveillance and reproof of others, which, rightly taken, will go far toward preparing us for the large Community above (Hinds 1961, 38). In addition to the economic benefits, the Zoar member quoted above emphasized the spiritual benefits of communal living: that charity and love for one another can be better fostered in a communal setting. Indeed, the spiritual aspect of communal living was often of primary importance. A number of Christian communities adopted communal living because they believed in following the example of the early Christian church as described in the New Testament Book of Acts of the Apostles. After the death of Jesus, the early Christians shared all their wealth and resources with each other, and no one was to own any private property. American communities influenced by the Book of Acts include Bishop Hill, Bohemia Manor, The Family/Children of God, The Farm, Harmony Society, the House of David movement, Jesus People USA, the Shakers, and the Zoar Society. Even if a community did not take its inspiration from the Book of Acts, the members might still choose communal living for spiritual reasons. The Moravians, who began settling in the United States in 1741, were a branch of an Eastern European Protestant sect. They discovered that members of a similar age and life situation encouraged each others’ spiritual growth, so in some of their communities, they organized their living arrangements into “choirs”—single women lived communally with other single women, single men lived with other single men, and married people lived in their own choirs. The Hutterites, a Christian Anabaptist sect (those who believe in adult baptism), fled Germany for the United States in 1874. For them, communal living is intimately tied to their spiritual beliefs. They believe that in order to return to God (from whom we were separated because of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace), one should live communally, share income and property, and remain separate from the rest of the world. Hutterites believe that the individual “self” must be broken, and that every person should work and live for the sake of the entire community. The Catholic Worker Movement, a socialist and anarchist spiritual movement founded in 1933 to serve the poor and needy, believes that its communal homes are a way “to live in accordance with the justice and charity of Jesus Christ,” according to its Web site. During the 1960s and 1970s, when the hippie youth movement led to the formation of perhaps a thousand utopian communities, young people joined such communities because of distrust with mainstream society and of the belief in the idea that by creating a new kind of society, they could create a new kind of human: one who is unselfish and free (Kephart 1978, 284–287). Why Do Some Utopian Communities Endure while Many Others Fail after a Few Years? There have been perhaps thousands of utopian communities formed throughout the history of the United States. Most were very small and/or very short-lived. Are there certain qualities or practices that help some communities to survive longer than a few years? In order to answer this question, Kanter compared 30 19th-century American communities: nine that lasted at least 33 years and 21 that lasted 15 years or less. The successful communities included the Shakers, the Harmony Society, Amana, Zoar, the Keil communities, Oneida, and Jerusalem. The unsuccessful communities included Brook Farm and other Fourierist phalanxes, Bishop Hill, and New Harmony and other Owenite communities (1972). Kanter concluded that the successful communities included more “commitment mechanisms” than the unsuccessful ones. In other words, the successful communities included more ways to cause members to be fully committed to the community. These commitment mechanisms allowed the communities to survive challenges such as poverty, illness, fire, persecution, and natural disasters. Without many commitment mechanisms, the unsuccessful communities tended to disband in the face of challenges (1972). Kanter identifies six commitment mechanisms that communities use. “Sacrifice” means that members must give up something in order to join. Members might commit to giving up alcohol, tobacco, rich foods, meat, fashionable dress, luxurious living arrangements, or sexual relations. Although one might expect that sacrifices would discourage people from remaining in a community, Kanter says the opposite occurs. “Once members have agreed to make the ‘sacrifices,’ their motivation to remain participants increases” (1972, 76). “Investment” is the idea that members must contribute property and/or labor to the community, and they may not be reimbursed for these when they leave. “Renunciation” involves giving up relationships outside of the community, and also weakening exclusive relationships within the community (such as couple or family relationships), so that members are connected strongly to the group as a whole, and not to individuals within or outside the community. “Communion,” the feeling of connectedness and belonging within the whole group, is fostered when members share work, meals, property, meetings, and celebrations. “Mortification” occurs when communities have practices to help members change their behavior to fit with the ideals of the community. For example, some communities used regular confession or public punishment of people who deviated from community rules. They might honor certain spiritually advanced people with leadership positions. “Transcendence,” the feeling of being part of something meaningful and awe-inspiring, can be fostered with a group ideology or philosophy that explains important aspects of humanity and the world and a leader who is seen as having spiritual or magical powers (1972, 75–125). These commitment mechanisms helped members to be more committed to the group as a whole, and to its survival, than to themselves or their biological families. How This Book Is Organized This book is organized to allow you to easily compare and contrast the utopian communities. For each community, information about when the community began and ended, the religious or other belief system, how the community earns money, how the leaders are chosen, how children are cared for and educated, and so forth are included. Separate entries are included on the philosophies and ideologies that influenced the formation of communal utopias, such as anarchism and socialism. Historic events of importance to communal utopias have separate entries as well, including the Industrial Revolution and the Great Depression. The book also covers topics of general concern, such as child rearing, education, leadership, the status of women, and pacifism. These topics will help you understand how different communities throughout history have dealt with these important issues. The chronology that follows this introduction will help you to put the various communal movements in perspective with other events in American history. You will notice that, while each community believes that it is doing things in order to live the best possible life, each has different views as to what that life should be like, and how to achieve it. References Bestor, Arthur Eugene. Backwoods Utopias: The Sectarian and Owenite Phases of Communitarian Socialism in America: 1663–1829. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950. Boyer, Paul. “Foreword,” in America’s Communal Utopias, edited by Donald Pitzer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997, ix–xiii. Brewer, Priscilla. “The Shakers of Mother Ann Lee,” in America’s Communal Utopias, edited by Donald Pitzer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997, 37–56. Hinds, William Alfred. American Communities. New York: Corinth Books, 1961. Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. Commitment and Community: Communes and Utopias in Sociological Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972. Kephart, William. Extraordinary Groups: The Sociology of Unconventional Life-Styles. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1978. Oved, Yaacov. Two Hundred Years of American Communes. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1988. Pitzer, Donald. “Introduction,” in America’s Communal Utopias, edited by Donald Pitzer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997, 3–13. Zablocki, Benjamin. Alienation and Charisma: A Study of Contemporary American Communes. New York: The Free Press, 1980. MLA Sreenivasan, Jyotsna. "Introduction." Utopias in American History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008. ABC-CLIO eBook Collection. Web. 14 May 2012.