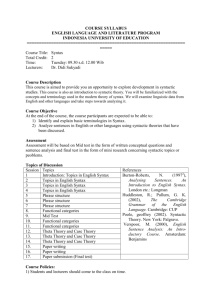

PowerPoint - Wayne State University

advertisement

WSU Humanities Center, 9/17/13 Ljiljana Progovac progovac@wayne.edu Acknowledgements For travel support, I am grateful for the WSU Distinguished Faculty Award and the Humanities Center Grant for Innovative Projects. For many good comments and discussions, my sincere thanks go to Martha Ratliff, Eugenia Casielles, John L. Locke, Paweł Rutkowski, David Gil, Jasmina Milićević, Draga Zec, Relja Vulanović, Tecumseh Fitch, Ana Progovac, Natasha Kondrashova, Steven Franks, Fritz Newmeyer, Andrea Moro, Noa Ofen, Ray Jackendoff, Željko Bošković, Ellen Barton, Kate Paesani, Pat Siple, Walter Edwards, Dan Seeley, Stephanie Harves, Igor Yanovich, Dan Everett, Andrew Nevins, Juan Uriagereka, Rafaella Zanuttini, Stephanie Harves, Richard Kayne, Brady Clark, Jim Hurford, Robert Henderson, Geoff Nathan, Margaret Winters, Daniel Ross, Pat Schneider-Zioga, as well as many (other) audiences at SLS (2006), MLS (2006, 2007), GURT (2007), ILA in New York (2007), the Max Planck Workshop on Complexity in Leipzig, Germany (2007), the ISU Conference on Recursion (2007), FASL (2007, 2008, 2012), AATSEEL (2007), the DGfS Workshop on Language Universals in Bamberg, Germany (2008), EvoLang, Barcelona (2008), BALE in York, England (2008), Novi Sad, Serbia (2008), Torún, Poland (2009), EvoLang, Utrecht, Netherlands (2010), University of Virginia, Charlottesville (2012), University of Washington, Seattle (2012), University of Western Ontario (2012), Duke Institute for Brain Sciences (2013). All errors are mine. 2 How did syntax evolve? Could it be via one single, minor mutation? Berwick (1998) “There is no possibility of an ‘intermediate’ syntax between a non-combinatorial one and full natural language—one either has Merge in all its generative glory, or one has no combinatorial syntax at all ...” Berwick and Chomsky (2011) “the simplest assumption, hence the one we adopt…, is that the generative procedure emerged suddenly as the result of a minor mutation. Language is something like a snowflake, assuming its particular form by virtue of laws of nature… Optimally, recursion can be reduced to Merge… There is no room in this picture for any precursors to language—say a language-like system with only short sentences. The same holds for language acquisition, despite appearances…” see also Bickerton’s (1998) “catastrophic evolution” 3 Gradualist stance Pinker and Bloom (1990): natural selection of complex systems Jackendoff (e.g. 1999, 2002): “living fossils” Progovac (e.g. 2008; 2009a,b): using the theory of syntax (Minimalism) to reconstruct stages of proto-grammar; reinforcing internal reconstruction with “living fossils” found in various modern languages (see also Heine and Kuteva (2007) for reconstruction based on the theory of grammaticalization) corroborating evidence and testing grounds: language acquisition (spoken and signed), aphasia, language disorders, genetics, neuroscience 4 Living fossils Jackendoff (2002): not only are previous stages present in the brain, but also ‘their “fossils” are present in the grammar of modern language itself Progovac (2008, 2009a,b): not only is fossil syntax still in use in certain modern language constructions, but this fossil syntax is built into the very foundation of more complex structures, providing evidence for evolutionary tinkering with the language design 5 Gradualist approach is feasible Pinker and Bloom (1990) assume the Baldwin Effect, the process whereby environmentally-induced responses set up selection pressures for such responses to become innate, triggering conventional Darwinian evolution. Tiny selective advantages are sufficient for evolutionary change: a variant that produces on average 1% more offspring than its alternative allele would increase in frequency from 0.1% to 99.9% of the population in just over 4,000 generations. This would still leave plenty of time for language to have evolved: 3.5-5 million years, if early Australopithecines were the first talkers, or, as an absolute minimum, several hundred thousand years, in the unlikely event that early Homo Sapiens was the first. Fixations of different genes can go in parallel. Sexual selection can significantly speed up the process. 6 In search for grammars producing short (and flat) sentences A host of constructions across languages point to such grammars So-called “small clauses” are used abundantly in adult languages (theoretically recognized concept) Children language acquisition proceeds through a two-word (arguably small clause) stage Verb-noun and other compounds (two-word molds) Intransitive absolutive-like structures (only one argument; no subject-object distinction) Unaccusatives (only one argument; subject-object distinction blurred) Middles (straddling the boundary btw. intransitivity and transitivity; passive and active; subjecthood and objecthood) Paratactic attachment of small clauses is binary (slides 22-24) Merge (of Minimalism) is binary: can only combine two elements at a time 7 Two-word intransitive stage Proposal: a two-word paratactic intransitive stage predated more complex syntax A two-word stage cannot accommodate both subjects and objects (with verbs); it must have been intransitive and absolutive-like, in the sense that no subject-object distinction was syntactically encoded Kegl et al. (1999), the earliest (pidgin) stages of Nicaraguan Sign Language do not use transitive NP V NP constructions, such as *WOMAN PUSH MAN. Instead, they use two paratactically combined (intransitive) clauses, an NP V — NP V sequence: (i) WOMAN PUSH — MAN REACT. (ii) WOMAN PUSH — MAN FALL. The only argument here is absolutive-like in the sense above 8 Homesign – absolutive-like? Goldin-Meadow (2005) The syntax of Homesign languages also seems absolutive-like: both patients/themes and intransitive agents tend to precede verbs, once again, neutralizing the distinction between subjects and objects There is typically only one argument per verb Both American and Chinese deaf children are more likely to produce the sign for the eaten than for the eater (real agents/subjects typically suppressed); this is also the case with fossils compounds, nominals, etc. 9 Ergative/absolutive patterns In some ergative languages (e.g. Tongan, Austronesian language), the subject of the intransitive clause is not distinguishable from the object, both appearing in the socalled absolutive case (Tchekhoff 1979, 409): (i) ‘oku kai ‘ae iká. PRES eat the fish ‘The fish eats.’ Or: ‘The fish is eaten.’ The subject of a transitive verb carries ergative marking (next slide), but the other two roles are collapsed into one, absolutive role Some analyze ergative arguments as optional adjuncts (e.g. Nash 1006; Alexiadou 2001) 10 Ergative added to absolutive base This intransitive absolutive layer provides foundation upon which one can add an ergative agent (one type of transition to transitivity): (i) Oku ui ‘a Mele (Tchekhoff 1973, 283) PRES call Mary ‘Mary calls.’ Or: ‘Mary is called.’ (ii) Oku ui ‘e Sione‘ a Mele PRES call by-John Mary ‘John calls Mary.’ Similar ergative-like patterns found in nominals (noun phrases) across (non-ergative) languages (e.g. Alexiadou 2001) (iii) John’s portrayal (by the media/of the media) was unfair (iv) John’s painting/portrait (by the artist) (v) John’s observation took 2 hours. (optional by-phrase likened to the ergative case, e.g. Comrie 1978) 11 Proposal: Absolutives as precursors to transitivity Specific proposal: Intransitive absolutive-like grammars predated transitivity in language evolution Such grammars involved a predicate and only one argument (two-word grammar) There was no distinction between subjects and objects Such absolutive-like patterns are available in various guises in all modern-day languages (fossils) They also serve as foundation for constructing more complex (transitive) structures 12 Compound fossils: Today’s morphology is yesterday’s syntax (Givón) Verb-Noun compounds are absolutive-like fossils: they fit into a two-slot syntactic frame (Progovac 2012) scare-crow, kill-joy, pick-pocket, cry-baby, cut-purse, busybody, spoil-sport, turn-coat, rattle-snake, hunch-back, dare-devil, wag-tail, tattle-tale, saw-bones, cut-throat, Burn-house, Love-joy, Pinch-penny (miser), sink-hole Typically, the noun is object-like, but can also be subjectlike, as in the underlined compounds No differentiation between subjects and objects; as with Homesign, preference for expressing the eaten, rather than the eater (Slide 9); see also nominals (Slide 11) 13 VN compounds across languages and times The same holds for Serbian and other languages ispi-čutura (drink.up-flask—drunkard), guli-koža (peel-skin—who rips you off), cepi-dlaka (split-hair— who splits hairs), muti-voda (muddy-water—troublemaker), jebi-vetar (screw-wind—charlatan), vrti-guz (spin-butt—fidget); tuži-baba (whine-old.woman; tattletale); pali-drvce (ignite-stick, matches) These compounds are now fossils in most languages, but they used to be productive and numbered in the thousands, e.g. in the medieval times 14 Compounding the Insult These VN compounds specialize for derogatory reference when referring to humans They provide evidence of ritual insult, and are thus of potential sexual selection significance (Progovac and Locke 2009) You can create many stunning insults with two-word grammars, not possible by using single words; also, you can create abstract vocabulary out of concrete concepts The vast majority of these compounds have not been preserved in dictionaries or grammar books, due to their “unquotable coarseness” 15 Syntactic reconstruction: Unraveling the syntactic layering Minimalism (e.g. Chomsky 1995): to derive a transitive sentence (i), the internal (object-like) argument starts in the VP (or Small Clause (SC)) (ii a), and the external argument (e.g. agent) in the outer vP shell (iib): (i) Maria will roll the ball. (ii) a.[SC/VP roll the ball] → b.[vP Maria [SC/VP roll the ball]] → Then Tense Phrase (TP) projects on top, and attracts the highest argument to become its subject (iic) c.[TP: Maria will [vP Maria [SC/VP roll the ball]]] 16 Every sentence starts as a small clause Modern syntactic theory (e.g. Minimalism and predecessors) analyzes every clause/sentence as initially a small clause (SC) (e.g. Stowell 1981, 1983; Burzio 1981; Kitagawa 1986; Koopman & Sportiche 1991; Chomsky 1995, and subsequent work) This is one of the most stable postulates of syntactic theory The TP layer is superimposed upon the layer of SC, as if the building of the modern sentence retraces its evolutionary steps 17 Syntax without vP: Unaccusatives (and absolutives) But it is possible to have syntax without a vP layer; according to e.g. Chomsky (1995) and Kratzer (2000), unaccusatives do not have a vP layer, i.e. transitivity layer: (i) The ball will roll/fall. (ii) a.[SC/VP roll/fall the ball]] b.[TP: The ball will [SC/VP roll/fall the ball]] Unaccusatives analyzed as Merging their “subject” in the object position (e.g. Burzio 1981; Perlmutter 1978) The highest argument moves to TP to become “subject” Notice how the SC/VP (absolutive layer) serves as foundation for transitive vP shells (Slide 16) 18 But you can remove the TP layer, too: Bare small clauses With unaccusative small clauses in Serbian, only one layer of structure is there, the [SC/VP] layer (e.g. Progovac 2008); the “subject” stays put, as there is no TP: (i) [SC/VP Pala vlada.] fall. PART government ‘The government collapsed.’ (“PART” stands for a participle form of the verb) Contrast full TPs: “Vlada je pala.” (same meaning as above) (ii) a. Small clause: [SC/VP pala vlada] b. [TP je [SC pala vlada]] c. TP [TP vlada [T’ je [SC pala vlada]]] Notice: SC/VP provides a foundation for building TP Both clause types are in productive use in Serbian 19 Gradual progression Gradual progression through 3 rough syntactic stages towards increased syntactic complexity: from one single layer of structure in TP-less, vP-less small clauses (absolutive-like stage) (Slide 19) to 2 layers of structure in TP unaccusatives (Slide 18) to 3 layers of structure with TP transitives (Slide 16) Each new layer brings a clear and concrete advantage, which could have been targeted by natural/sexual selection (see below) There are even intermediate steps leading from intransitives to vP transitives, so-called “middles” (slides 29-33) 20 Reconstruction based on syntax Proposed internal reconstruction is based on the theory of syntax (Minimalism, e.g. Chomsky 1995): A structure X is considered to be (evolutionary) primary relative to a structure Y if X can be composed independently of Y, but Y can only be built upon the foundation of X While small clauses/VPs can be composed without the vP or TP layers, vPs and TPs need to be built upon the foundation of a small clause/VP this hierarchy of functional projections (e.g. Abney 1987) is a theoretical construct, with good empirical foundation 21 Converging with Heine and Kuteva (2007) This reconstruction, based on the theory of syntax, converges with that of Heine and Kuteva (2007), which is based on grammaticalization processes Grammaticalization almost always creates a functional category out of a lexical category, and almost never the other way around Conclusion: functional categories emerged gradually at a later stage of language evolution There could have existed a stage with only nouns and verbs (enabling two-word grammars) 22 Are “living fossils” really that much simpler? Living fossils of the simplest proto-syntax are rigid, non-moving, non-recursive structures: Cannot embed (no recursion): (i) a. *Ja mislim [(da) pala vlada]. I think (that) fell government b. Contrast full TP: Ja mislim [da je pala vlada]. The same holds for the comparable fossils in English: (ii) Problem solved. *I think that [problem solved.] *I consider [problem solved.] You can be cognitively fully capable of recursion, but if your syntax lacks the appropriate functional categories and structures, you cannot express it. 23 Merge is not all you need No Move either: (i) a. *Kada pala vlada? when fell government b. Contrast: Kada je pala vlada? (ii) a. *When/*How problem solved? b. When/How was the problem solved? Move and Recursion are not an automatic consequence of Merge (as claimed in e.g. Fitch, Hauser & Chomsky 2005); instead, one also needs functional categories and layered/hierarchical syntax 24 More English fossils (i) a. Case closed. Crisis averted. Point taken. Mission accomplished. Lesson learned. b. Me first! Family first! Everybody out! Small clause flat grammars allow only paratactic/ symmetric clause unions (ii) Nothing ventured, nothing gained. Easy come, easy go. Monkey see, monkey do. Come one, come all. No money, no come. (e.g. pidgin languages) 25 Similar fossils across languages Twi (spoken in Ghana); Kingsley Okai (p.c.) (i) Wo dua, wo twa you sow you reap (ii) Wo hwehwea, wo hu you seek you find Serbian (iii) Preko preče, naokolo bliže. ‘Across shorter, around closer.’ (iv) Koliko para, toliko i muzike. how-much money, that-much music 26 More binary data Latin: (1) a. Bene diagnoscitur, bene curatur well diagnosed, well cured b. Cito maturum, cito putridum early ripe, early rotten Even deep wisdoms can be expressed, and often are, with the simplest of grammars True living fossils: Such binary combinations are productive in some languages, e.g. Hmong (Martha Ratliff, p.c.) (2) a. ua noj ua haus make eat make drink 'to earn a living’ b. kav teb kav chaw rule land rule place 'to rule a county' Unaccusative small clauses in Serbian are also living fossils 27 Only binary unions But notice that these paratactic (symmetric/non- hierarchical) unions are almost always binary (twoslot grammars) (i) No shoes, no shirt, no service (exception) (ii) ??Nothing ventured, nothing gained, nothing lost. Our brains are at a loss as to how to process e.g. (ii) Binary Merge in syntax may have its roots in this processing limitation: Merge can only combine 2 elements at a time 28 Evidence for an absolutive-like intransitive stage Recall: Absolutive-like fossils found in all languages, including nominative-accusative (e.g. compounds; nominals); provide common ground for all language types Crosslinguistic variation reflects different paths taken from there (ergative-absolutive vs. nominative-accusative types) Nicaraguan Sign Language and Homesign Further evidence: Middles: transitional structures, straddling the boundary between intransitivity and transitivity Language acquisition Potential testing grounds: neuroimaging 29 The “middle” ground According to e.g. Kemmer (1994, 181), “the reflexive and the middle [are] … semantic categories intermediate in transitivity between one-participant and two-participant events.” There is an amazing array of such ambivalent, transitional structures across various languages, blurring the distinctions between subjects and objects, passives and actives, transitivity and intransitivity Exactly what one expects under a gradualist approach to the evolution of syntax; puzzling otherwise 30 Unbearable vagueness of meaning Middle se in e.g. Serbian exhibits astounding vagueness, reflexivity being only one of the available interpretations: (i) Deca se tuku. children hit SE ‘The children are hitting each other/themselves.’ ‘The children are hitting somebody else.’ ‘One hits/spanks children.’ (ii) Marko se udara! Marko SE hits ‘Marko is hitting me.’ [most salient discourse participant] ‘Marko is hitting somebody.’ ‘Marko is hitting himself.’ 31 Se in Spanish Comparable vagueness also found with se constructions in Spanish (Arce-Arenales, Axelrod, and Fox 1994, 5): (i) Juan se mató. Juan SE killed ‘Juan got killed.’ ‘Juan killed himself.’ See also English passive-like structure: (ii) The children got dressed. This vagueness is reminiscent of absolutives in Tongan (slide 9) 32 Se as a proto-transitive marker This is essentially the vague absolutive-like pattern, to which se is added, analyzed here as a proto-transitive marker (Progovac, to appear) Se just indicates that there is one more participant involved in the event, but the rest is left to context Se also occurs with dative subjects in Serbian, another fossil with a hint of ergativity In syntax, se has been analyzed as an expletive (meaningless) pronoun in the object position (e.g. Franks 1995; Progovac 2005). 33 Many other hints of ergativity in nominative-accusative languages DuBois (1987) has noted that the kind of pattern in which the eaten is expressed more readily than the eater, is common in the languages of the world: (i) a. John grew tomatoes. b. John grew. (ii) a. John shook Bill. b. John shook. Fluidity of the concept “subject” 34 Interim summary Method: internal reconstruction of syntax based on the theory of syntax (Minimalism), coupled with the search for fossils The initial stage of syntax -- protosyntax: Two-word grammars (e.g. predicate + one argument) Intransitive and absolutive-like No distinction between subjects and objects No syntactic layering (no vP or TP); flat structure No move or recursion A host of fossils in modern languages still show (at least some) of these properties: VN compounds, absolutives, unaccusatives; nominals, dative subjects 35 Summary cont. Supporting evidence: “Living fossils” used alongside more complex constructions Fossils are built into the very foundation of complex structures; e.g. an intransitive small clause (VP) is built into transitive vP shells, as well as into TPs This kind of tinkering is expected under a gradualist approach to the evolution of syntax, but is puzzling otherwise Corroborating evidence and testing grounds: language acquisition (spoken and signed), aphasia, language disorders, language representation in the brain 36 Analogy with the development of the heart My analysis of small clauses intergrading into full sentences/TPs resembles the development of the human heart (Garrett Mitchener, p.c.) The embryo initially has only a simple, primitive precursor to the heart, consisting only of two simple tubes, which merge, but even such primitive heart can perform the necessary rudimentary function The precursor gradually bulges and expands into a complex heart in the course of fetal development 37 Are reversals and losses possible? Dawkins: body hair can recede and reappear a number of times in the history of a species Some recent genetic studies reveal that reversals and losses are possible even in the evolution of multi-cellularity, a major transition in the history of life. Schirrmeister, Antonelli, and Bagheri (2011) report that the majority of extant cyanobacteria, one of the oldest phyla still alive, including many single-celled species, descend from multi-cellular ancestors, and that reversals to unicellularity occurred at least five times. Languages can also sometimes “undress” (McWhorter 2011) 38 Child syntax – absolutive-like? Two-word stage in L-1 acquisition (e.g. Bloom 1970) Children are claimed to “delete” arguments in their speech Zheng and Goldin-Meadow (2002): such “deletions” follow an ergative/absolutive pattern Children omit transitive subjects and produce intransitive subjects and objects (absolutive-like grammar); see Homesign and compounds (slides 9, 13) Zheng and Goldin-Meadow (2002): the ergative/ absolutive pattern is more robust; characterizes the speech of both hearing children and deaf children 39 Can syntax be adaptive? Only if you can decompose it into appropriate stages E.g. the capability to create 2-word insults (compounds) increases fitness (Progovac & Locke 2009); sexual selection vP introduces transitivity and with it more precision/less vagueness; can grammatically distinguish subjects from objects TP: break away from the prison of the here-and-now, and from the prison of pragmatics in general Displacement only possible with complex/hierarchical grammars Nested recursion (e.g. embedding one viewpoint within another) only possible with complex/hierarchical grammars (e.g. “John believes that Peter knows that Mary left town.” vs. “John believes that. Peter knows that. Mary left town.”) 40 Displacement and vP-less grammars Displacement (also recursion) is one of the design features of human language (Hocket 1960) One word (pre-syntactic) stage: (i) Apple. Eat. John. Two-word (absolutive-like) stage: (ii) Apple eat. John go. Hierarchical TP/vP stage: (iii) John will eat the apple. (iv) The apple will eat John. Only elaborated grammars allow the depiction of nonpresent, strange, or non-existent situations, because they can escape the prison of context (imagination, innovation) 41 Displacement and TP-less grammars TP-less small clauses typically rooted in the here and now: (i) Problem solved (*three years ago). (ii) Me first (*three years ago). Full TPs can escape into the past, the future, or the counterfactual (try expressing these with 2-word grammars): (iii) The problem was solved three years ago. (iv) The problem will be solved tomorrow. (v) The problem would have been solved if it wasn’t for a computer glitch. 42 Agrammatism Kolk (2006): with Dutch and German agrammatic speakers, preventive adaptation results in a bias to use simpler syntactic constructions, including root small clauses and root infinitives Whereas control speakers produced 10% non-finite clauses, aphasics produced about 60% In children, the overuse of non-finite clauses decreased with age: from 83% in the 2-year-olds, to 60% in the 2.5-year-olds, to 40% in the 3-year-olds A PET study by Indefrey et al. (2001) shows that nonfinite clauses require less grammatical work 43 Specific Language Disorder Specific Language Disorder is characterized, among other symptoms, by the delay or deficit in the use of auxiliary verbs, tense and agreement (TP elements), as well as of other functional categories A mutation on FOXP2 gene responsible for the disorder (Lai et al. 2001); mutation underwent selection Some recent experiments suggest that the specifically human FOXP2 mutations are responsible for growing longer neurites (axons and dendrites) in the brain, establishing better connectivity among neurons (Sonja Vernes, Max Planck Institute, LSA Institute Workshop Lecture, New Insights from Genetics, June 29, 2013). This was established by copying human mutations into the FOXP2 of mice. 44 Synergy While syntactic theory can help identify protostructures, and distinguish them from more complex structures, neuroscience can test if these distinctions are correlated with a different degree and distribution of brain activation, and genetics can, among other possibilities, shed light on the role of some specific genes in making such connections in the brain possible. 45 Correlations and subtractions Converging evidence in the literature showing that increased syntactic complexity corresponds to increased neural activity in certain specific areas of the brain (see e.g. Caplan 2001; Indefrey et al. 2001; Just et al. 1996). Pallier et al. (2011) found a positive correlation between the levels of hierarchical structure and the degree of activation; used 12 word strings, varying whether these 12 words were a single sentence, two or more shorter sentences, or just random strings. Brennan et al. (2012): a naturalistic 12-minute story-telling experiment. Each word in the story was analyzed for its level of hierarchical embedding, and the degree of embedding was found to correlate with the amount of activation in the anterior temporal lobes, as well as in the left posterior temporal lobe, left IFG, and medial prefrontal cortex. 46 Some predictions for proto-grammars (joint work with Noa Ofen, WSU Gerontology/Pediatrics) While the processing of TPs and transitives with vP shells is expected to show more clear lateralization in the left hemisphere, with more extensive activation of the Broca’s areas, the processing of proto structures, root small clauses and absolutive-type constructions, as well as middles, is expected to show less lateralization, and less involvement of the Broca’s areas, but more reliance on both hemispheres, as well as, possibly, more reliance on the subcortical structures of the brain (e.g. Lieberman 2000) 47 Fossils are often formulaic (i) Noting ventured, nothing gained. Easy come, easy go. (ii) Problem solved. Case closed. Point taken. Mission accomplished. (iii) Pala karta. ‘Card laid, card played.’ (Serbian) (iv) (v) fell.PART card Prošo voz. ‘The opportunity has passed.’ gone.PART train Preko preče, naokolo bliže. ‘Across shorter, around closer.’ Code (2005: 317): stereotypical/formulaic uses of language might represent fossilized clues to its evolutionary origins they involve more ancient processing patterns, including more involvement of the basal ganglia, thalamus, limbic structures, and the right hemisphere (also van Lancker & Cummings 1999; Bradshaw 2001) 48 Conclusion There is ample room for a language system with only short and flat (intransitive, absolutive-like) sentences; such (fossil) structures still live in various guises in all human languages This approach combines a reconstruction method based on syntactic theory with identification of syntactic fossils Fossil structures are shown to be built into the very foundation of more complex structures, thus explaining many properties of the language design itself, as well as language variation This approach is compatible with natural/sexual selection: each new layer of structure brings concrete and tangible incremental advantages, at least some of which could have been targeted by selection (e.g. two-word insults; less vagueness; displacement; transitivity; the expression of tense; nested recursion) This approach can mediate among the fields of syntax, neuroscience, and genetics; evolutionary considerations provide the point of contact 49 Thank you! 50