Neutrality Acts

Neutrality Acts – From Salem Press History

Attempting to prevent U.S. involvement in a foreign war, Congress passed four neutrality laws that limited the ability of the United States to provide assistance to countries that were at war with

Germany and Japan.

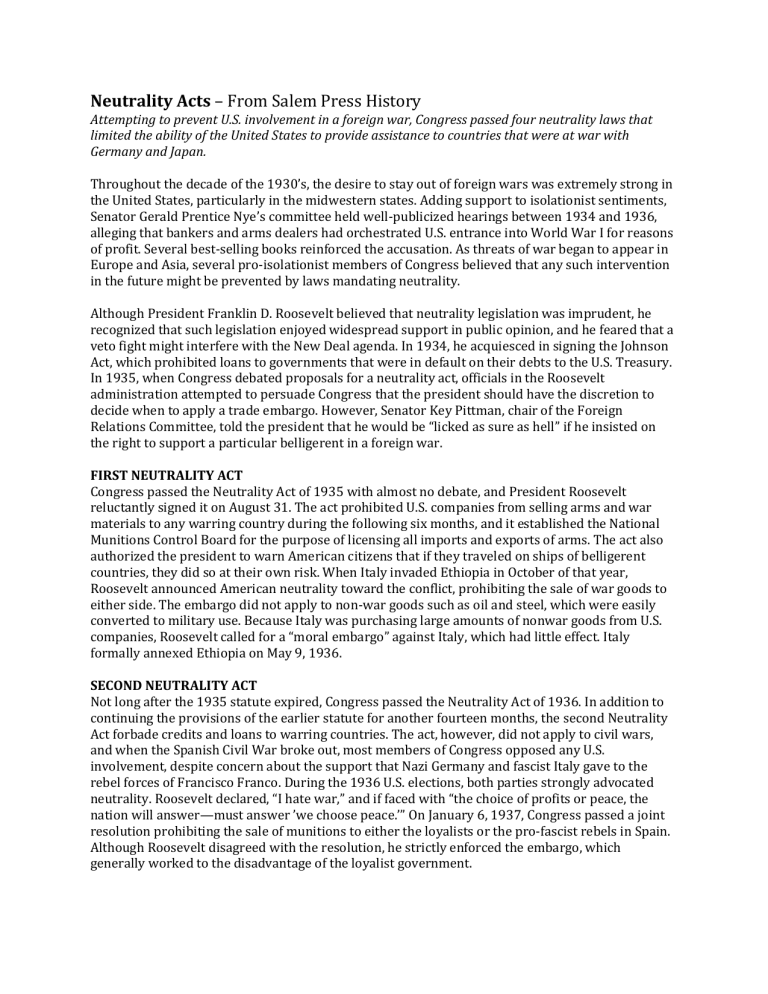

Throughout the decade of the 1930’s, the desire to stay out of foreign wars was extremely strong in the United States, particularly in the midwestern states. Adding support to isolationist sentiments,

Senator Gerald Prentice Nye’s committee held well-publicized hearings between 1934 and 1936, alleging that bankers and arms dealers had orchestrated U.S. entrance into World War I for reasons of profit. Several best-selling books reinforced the accusation. As threats of war began to appear in

Europe and Asia, several pro-isolationist members of Congress believed that any such intervention in the future might be prevented by laws mandating neutrality.

Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that neutrality legislation was imprudent, he recognized that such legislation enjoyed widespread support in public opinion, and he feared that a veto fight might interfere with the New Deal agenda. In 1934, he acquiesced in signing the Johnson

Act, which prohibited loans to governments that were in default on their debts to the U.S. Treasury.

In 1935, when Congress debated proposals for a neutrality act, officials in the Roosevelt administration attempted to persuade Congress that the president should have the discretion to decide when to apply a trade embargo. However, Senator Key Pittman, chair of the Foreign

Relations Committee, told the president that he would be “licked as sure as hell” if he insisted on the right to support a particular belligerent in a foreign war.

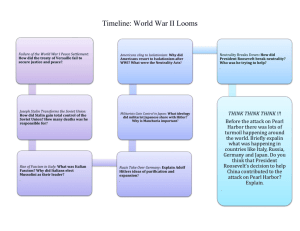

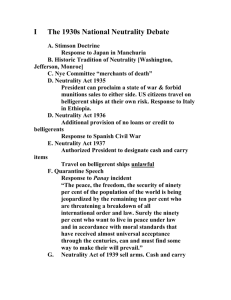

FIRST NEUTRALITY ACT

Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1935 with almost no debate, and President Roosevelt reluctantly signed it on August 31. The act prohibited U.S. companies from selling arms and war materials to any warring country during the following six months, and it established the National

Munitions Control Board for the purpose of licensing all imports and exports of arms. The act also authorized the president to warn American citizens that if they traveled on ships of belligerent countries, they did so at their own risk. When Italy invaded Ethiopia in October of that year,

Roosevelt announced American neutrality toward the conflict, prohibiting the sale of war goods to either side. The embargo did not apply to non-war goods such as oil and steel, which were easily converted to military use. Because Italy was purchasing large amounts of nonwar goods from U.S. companies, Roosevelt called for a “moral embargo” against Italy, which had little effect. Italy formally annexed Ethiopia on May 9, 1936.

SECOND NEUTRALITY ACT

Not long after the 1935 statute expired, Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1936. In addition to continuing the provisions of the earlier statute for another fourteen months, the second Neutrality

Act forbade credits and loans to warring countries. The act, however, did not apply to civil wars, and when the Spanish Civil War broke out, most members of Congress opposed any U.S. involvement, despite concern about the support that Nazi Germany and fascist Italy gave to the rebel forces of Francisco Franco. During the 1936 U.S. elections, both parties strongly advocated neutrality. Roosevelt declared, “I hate war,” and if faced with “the choice of profits or peace, the nation will answer—must answer ’we choose peace.’” On January 6, 1937, Congress passed a joint resolution prohibiting the sale of munitions to either the loyalists or the pro-fascist rebels in Spain.

Although Roosevelt disagreed with the resolution, he strictly enforced the embargo, which generally worked to the disadvantage of the loyalist government.

THIRD NEUTRALITY ACT

The Neutrality Act of 1937, enacted on May 1, required belligerent countries to pay cash for all nonwar materials and to transport them in their own ships. The act continued the ban on war materials and prohibited Americans from traveling on ships of belligerents. One provision authorized the president to decide when nations were at war and which materials were classified as war materials. In public opinion polls more than 68 percent of respondents said that they approved of the act and wanted it to be strictly enforced. In July, when Japanese troops invaded the

Chinese mainland, Roosevelt wanted to help China and initially declined to designate the conflict as a war. Nevertheless, on September 14, he forbade the transportation of materials to either China or

Japan in government vessels, and he notified private companies that any shipments would be at their own risk. On October 5, he called for an international quarantine on “bandit nations” guilty of aggression. Faced with overwhelming opposition, however, he quickly backed away from the suggestion. During the Munich crisis of 1938, he encouraged compromise with Hitler and made clear to Great Britain and France that the United States would not provide assistance in the event of war.

FOURTH NEUTRALITY ACT

On September 21, 1939, three weeks after Nazi Germany invaded Poland, Roosevelt called Congress into special session and requested that the cash-and-carry provision of the last neutrality act be amended to allow for the exports of war materials to belligerent countries. Although neutral in appearance, the proposal was clearly designed to help Britain and France, because the British Royal

Navy prevented German ships from reaching American ports. Despite the fierce opposition of isolationists, Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1939, which included Roosevelt’s recommendation. Without the arms and supplies purchased under the act, the British would have almost certainly not been able continue their struggle. On December 21, 1940, the German government denounced U.S. assistance to Britain as “moral aggression.”

IMPACT

Most modern historians are critical of the first three of the Neutrality Acts because they provided no distinctions among aggressive countries and victims. By insisting on no assistance to any belligerent country, the isolationists responsible for the acts refused to make a choice in favor of the lesser of two evils. The Neutrality Act of 1939, with its cash-and-carry provisions, constituted a major departure from a policy of strict neutrality, and it meant that a future war with Nazi Germany was likely, but perhaps not inevitable.

Responding to Roosevelt’s state of the union address that included an appeal for Congress to repeal the cash-and-carry requirements in the 1939 act, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act, which allowed the president to transfer, sell, or lease war goods to any country that he considered vital to the defense of the United States. Within a few months, the Lend-Lease Act resulted in an undeclared naval war with Germany. On November 13, four days after a German submarine sank the U.S. destroyer Reuben James, Congress repealed all significant restrictions still remaining in the

Neutrality Acts, allowing merchant vessels to arm themselves and to carry cargoes to belligerent ports.