File

advertisement

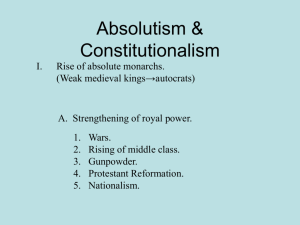

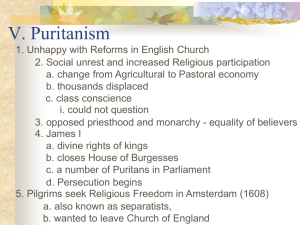

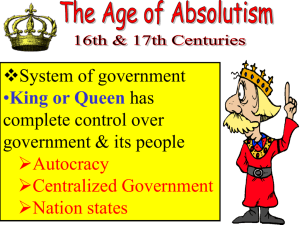

AGE OF ABSOLUTISM Part 6 – Constitutionalism in Britain Constitutionalism: While the question of sovereignty was resolved in France, Prussia, and Russia with the emergence of an absolutist government; England (and Holland also) developed constitutional states. Constitutionalism is the limitation of government by law. It implies a balance between the authority and power of the government and the rights and liberties of the individual. That balance is often quite delicate. A constitution, whether written or unwritten (the English constitution is unwritten) gets its authority from the acknowledgement that the government must respect it; in other words, the state must govern according to the law. People regard the law and the constitution in such a state as the protector of their rights, liberties, and property. Modern Constitutional governments may either be republics or monarchies. If a republic, power resides in the electorate and is exercised by the electorate’s representatives. A classic example is the government of the United States. In a constitutional monarchy, a king or queen serves as the head of state, and may possess some residual political power, but the ultimate sovereign power again rests with the electorate. A classic example is the parliamentary government of Great Britain. It is important to note that a constitutional government is not the same as a democratic government, although it may possess democratic qualities. In a complete democracy, all the people have the right to participate, either directly or indirectly in the government of the state. Such a government is often tied up with the idea of the franchise (right to vote). Full democracy was only achieved recently, when women were given the right to vote. The Decline of Royal Absolutism in England: Elizabeth I had enjoyed extraordinary success as Queen of England, because she was a shrewd political master. She carefully managed finances, selected ministers wisely, and cleverly manipulated Parliament without losing her sense of royal dignity. She remained devoted to hard work. During her later years, she refused to discuss the succession. Upon her death in 1603, James Stuart, James VI of Scotland, the son of her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots, became James I of England. That same year, Parliament passed the Act of Union which combined England and Scotland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. James was well educated, learned, and had thirty five years experience as King of Scotland. However, he did not possess Elizabeth’s love of the majesty of the throne, or the dignity which surrounded it. In a society hostile to all things Scottish, his Scottish accent won him no friends. James was intelligent and well read, but also lazy, frivolous, and slovenly. He seemed to take great joy in throwing jelly at his courtiers. He was once described as the "wisest fool in Christendom." When dealing with the public at large, he displayed all the tact and finesse of a drunken Indian on a surf board. Immediately after his coronation, when he was urged to wave to the throng who had gathered to cheer their new king, he complained that he was tired, and threatened to drop his breeches, “so they can cheer my arse. .In stark contrast to Elizabeth, James was an exceptionally poor judge of character. He was devoted to the idea of Divine Right of Kings, and expressed his ideas in an essay entitled "The Trew Law of Free Monarchy," in which he argued that a monarch has a God given right to his authority, and is responsible only to God. Rebellion was the worst of political crimes. If a King ordered something evil, his subjects should respond with passive disobedience, but should be prepared to accept the penalty for disobedience. In a speech delivered in 1609, he also once lectured the House of Commons that "there are no privileges and immunities which can stand against a divinely appointed King." He called "the state of monarchie…the supremest thing on earth: for Kings are not only God’s Lieutenants upon earth, and sit upon throne, but even by God himselfe they are called Gods." He described Parliament as nothing but "cries, shouts and confusion." Needless to say, his relationship with Parliament went downhill fast. James’ remarks were a serious political mistake. Although he had correctly stated the Stuart concept of Absolutism; by doing so he had taken a stand directly in conflict with long standing concepts of English liberty, including the idea that one’s property could not be taken without due process of law. Parliament, specifically the House of Commons, closely guarded the national purse at a time when James and the later Stuart Kings badly needed revenue. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that Elizabeth had left him with a substantial debt. The English monarchy to which James ascended was not that of Henry VIII. The dissolution of the monasteries and sale of church lands had made many people rich. Agricultural techniques such as the use of fertilizer, had increased crop yields, and the old system of manorial common land evolved into enclosures and sheep runs. Many people invested in commercial ventures, including the cloth industry. A number of partnerships and joint stock companies engaged in foreign enterprises, such as The Virginia Company, the Plymouth Company, and The Royal African Company. (Jamestown, Virginia, founded in 1607, was named for James, as was the James River.) Commercial capitalism had made a number of Englishmen quite wealthy. This had produced a better educated and more articulate House of Commons. Many members had some knowledge of legal matters which they used to argue against the King. Prudent financial management could have reduced the debt which James inherited. However, he considered any money which came into his hands as a windfall which he could spend on lavish displays and extravagances. James’ reputation was not helped by his public flaunting of a number of his male lovers. Unlike France, there was no social stigma to paying taxes. The members of the House of Commons had no qualms about taxing themselves, provided they had some say in how those taxes were spent, and the governmental policy which those taxes paid for. James and his Stuart successors, however, considered this an inexcusable effront.to the royal prerogative. At every Parliament between 1803 and 1640, bitter disputes between the King and the Commons erupted. Religious differences exacerbated an already difficult situation. An increasing number of Protestants were not happy with the established Church of England. Many believed that the church retained too many elements of "popery," and wished to "purify" it of any Catholic elements. (Among the practices to which they objected were church vestments and ceremonials, the position of the altar in the church, and the giving and wearing of wedding rings.) They were soon denominated by the derogatory term, "Puritan," which soon became their commonly accepted name. They were also attracted by the Calvinist concept of hard work, sobriety, thrift, postponement of pleasure, (the so-called Protestant work ethic) as well as the tendency to link sin and poverty with weakness and moral corruption. The term "Puritan" was meant as a term of abuse. The Puritans called themselves "the Godly," they believed that they represented the true Church of England. The English Puritans were much surer of that which they were against than what they were for. They were strong believers in the Calvinist concept of predestination, and the individual’s understanding of the Bible. They opposed the role of bishops, played down the significance of the sacraments, and supported a simpler form of worship. They were intently hostile to church ceremony and ritual, stained glass windows, and altar rails, James was Calvinist, but hardly Puritan. When the Puritans wanted to abolish Bishops in the Church of England, James replied, "No bishop, no king." His meaning was that the Anglican bishops were the chief supporters of the King; however the Puritans considered it a challenge. In the last year of his reign, James became more and more dependent upon his young, handsome favorite, George Villiers, the duke of Buckingham. Buckingham was new to court policies, and convinced the king to sell titles of nobility, (a la the French) public offices, and other privileges to the highest bidder. Parliament during this time gradually transformed itself from a debating society with little power to an institution which saw itself as the guardian of the rights and privileges of the people. An example of this new attitude was the Impeachment of Sir Francis Bacon, a philosopher and man of science, and the king’s friend. The principle at stake was the accountability of the Kings ministers to Parliament. Parliament increasing exerted its authority over matters of state. Queen Elizabeth had denied that Parliament had the right to discuss matters of foreign policy unless invited by the crown to do so; however Parliament insisted on that right. When James favored peace with Spain, Parliament favored war, since Spain was Catholic. When James arranged for the marriage of his son Charles to the daughter of Philip IV of Spain, Parliament objected, arguing that this would constitute a pro-Spanish foreign policy, and that it had a right to discuss marriages which constituted affairs of state. James replied that Parliament could not discuss matters of foreign policy y and stating that the privileges of Parliament were not "your ancient and undoubted birthright and inheritance;" rather they were "derived from the grace and permission of our ancestors and us." As luck would have it, the marriage fell through. In 1613 when Charles, accompanied by the Duke of Buckingham (his father’s "favorite," Philip would not let him even lay eyes on his daughter. James then arranged Charles’ marriage to Henretta Maria of France, a devout Catholic, as had been Philip’s daughter. The terms of the marriage included a promise by James that he would one day allow English Catholics (about 3 per cent of the population) to practice their religion freely. This act was seen by many as another step by James to move the country back to Catholicism. James was succeeded by his son, Charles I, who was also Calvinist, but gave the impression of being sympathetic to Roman Catholicism. Charles was indecisive and shy, and plagued with stammering speech. Even more than had his father James, he rejected the idea that his appointments to public office should represent a variety of views and political opinions. During Charles’ reign, the religious debate intensified. Charles deeply believed in the rituals of the Church, and was favorable to a form of Protestantism known asArminianism. Arminian theology rejected predestination; rather they believed that salvation was obtained by free will. They accepted the use of rituals in church services, and emphasized the authority and ceremonial role of Bishops. They also supported the authority of the King over the Church of England and thereby seemed to support the idea of absolute rule. All the tenets they supported were anathema to the Puritans. The Puritans considered this "popery," elements of Catholicism. They associated Catholicism with the St. Bartholomew Day’s massacre, the Spanish Inquisition, and Alba’s Council of Blood. In 1633, Charles named William Laud (1573-1645) as Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud was pious and hardworking, but stubborn. Laud was an Arminian who espoused Church ritual, which made the Puritans view him with suspicion, as they believed he was secretly working to make Roman Catholicism the official religion of England.. In fact, Laud warned Charles that the religious extremes of Catholicism and Puritanism posed threats to the Anglican Church, and "unless your Majesty look to it, she will be ground to powder." Laud, who insisted on uniformity of worship, enforced Church doctrine through a "Court of High Commission." He attempted to impose two new elements on the church in Scotland: A new prayer book modeled after the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, and imposition of bishoprics on the Scottish church. Laud’s efforts caused a revolt in Scotland, and Charles was forced to recall Parliament for financial aid in fighting the war. Parliament and Charles I Clash: Charles made every attempt to raise money without convening Parliament. In 1625, he decreed a forced loan on landowners, which were to be paid within three months, a period of time which made it almost impossible to comply. When a number of gentlemen, including five prominent knights, refused to honor his demand, Charles had them imprisoned. Desperate for money, Charles convened three Parliaments within four years, but dismissed each when they refused to levy taxes unless he met their demand for fiscal reform. They also insisted that Charles appoint ministers whom Parliament could trust, and commenced impeachment proceedings against the Duke of Buckingham, his father’s favorite. The impeachment was never completed as Buckingham was assassinated in 1628 by a naval officer who was unhappy at not being paid. Charles again asked Parliament for funds, to which it responded with the Petition of Right, which Charles was forced to accept in exchange for Parliament’s assent to a tax. The Petition stated that the King would not impose "loans" without Parliament’s consent, and that no "gentleman" who refused payment would be arrested without a show of just cause. The Petition of Right was a significant development in English constitutional rights. Charles was angered by the Petition, and ordered Parliament dissolved. The Speaker of the House was responsible for notifying the king of the Acts of Parliament, but members of the chamber physically held him in his chair so he could not leave. They then declared that anyone who attempted to collect funds not approved by Parliament or who sponsored "innovation of religion" would be considered "a capital enemy to the kingdom and commonwealth." Parliament disbanded after the above action, and Charles ruled alone for eleven years. Rather than recall Parliament to raise money, he tried innovative ways, including fining those who did not appear for his coronation and levying taxes for "ship money" (money collected from port areas to pay the costs of the royal navy) on inland areas. The levy was challenged in court but the judges, who had been bought off, ruled in Charles’ favor. Unlike his French counterparts or his father, Charles did not sell titles of nobility, a surprising policy in light of his desperate attempts to raise funds. Charles’ policies and Laud’s interference in the Scottish church resulted in a revolt in Scotland. Desperate for money, Charles demanded a large sum of money from the city of London. London agreed, but on condition that Charles convene Parliament, and prove his good faith by allowing Parliament to set for a sufficient period of time. In April, 1640, Charles summoned Parliament for the first time in eleven years; but when Parliament refused to allocate money until the King considered a list of grievances, he ordered it dissolved after less than two months. Those who supported Parliament in its dispute with the King became known as supporters of "Country," while those who supported the throne were identified with "Court." The failure of the two sides to come to terms led to the English Civil War. Both sides were stubborn and unyielding. Parliament was led by a Puritan, John Pym, 1584-1643) who was zealous to the point of paranoia. He was obsessed with a "popish plot" to restore Catholicism to England At the same time, Laud expanded the power of church courts to try persons accused of offenses against the Church of England—a policy which to many smacked of the Spanish Inquisition. The English Civil War: Charles was forced to call a new Parliament within a few months. This new Parliament, called the "long Parliament," sat twenty years. It passed the Triennial Act which required the King to summon Parliament every three years, impeached Archbishop Laud, and abolished the Court of High Commission. Charles was fearful of a Scottish invasion and accepted the terms. Even so, there was no peace between King and Parliament. Radical members of Parliament pushed increasingly severe measures which the King would hardly accept, and Charles attempted to renege on the concessions he had already made. In the meantime, a revolt broke out in Ireland where peasants (overwhelmingly Catholic) killed a number of Protestant landlords. The situation was dire. In November,1641, Parliament narrowly passed the Grand Remonstrance, which decried "a malignant and pernicious design of subverting the fundamental laws and principals" of English law, and called for a number of reforms. Shortly thereafter, the high sheriff of London called upon "gentlemen" and their tenants to take arms on the king’s behalf "for the securing of our own lives and estates which are now ready to be surprised by a heady multitude." Charles, emboldened by bad advice from members of his court, led several armed soldiers against Parliament in January, 1642, but Pym and other Parliamentary leaders, forewarned, fled before he arrived. Charles became fearful of his own safety, as the general populace of London increasingly supported Parliament, and moved his family to friendlier territory in the north. The Civil War was on. Parliament’s soldiers were known as "roundheads" because of the short bowl-shaped haircuts they wore. The king’s supporters fancied themselves as fighting the good fight for God and king, and thus were called "Cavaliers." There were few actual battles, the war was more a war of words, with over 2,000 pamphlets published, an average of six per day. Still, life for many villagers was disrupted: ten percent of the English population was forced to leave home during the war. In June, 1645, the King's forces were defeated, and Charles surrendered to the Scots, but the Scots left him in the custody of Parliament. In November, 1647, Charles escaped and fled to the Isle of Wight. While there, he attempted to secure cooperation with the Scots, but failed, and was "more a prisoner than ever, and could not goe to pisse without a guarde nor to Goffe" [to play Golf]. Parliament, under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell, passed a motion that no further addresses would be made to the King. Charles’ days were apparently already numbered. A "Rump Parliament" consisting of about a fifth of the legitimate members, appointed a High Court to try Charles on charges of high treason. Charles refused to defend himself, and was found guilty. On January 30, 1649, he was beheaded, the first monarch to be executed by his own subjects. Charles' execution gave rise to a nursery rhyme still popular today: Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall. Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. All the King's Horses, and all the King's Men Couldn't put Humpty together again. Part 7 – More Constitutionalism in Britain The Interregnum: When Charles I was executed on January 30, 1649, the Rump Parliament abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords and a Commonwealth, or republican form of government was proclaimed. That government theoretically consisted of the surviving members of Parliament and a council of state which exercised the executive power. In reality, the government was transformed into a military dictatorship: The army that defeated Charles controlled the government and the army was controlled by Oliver Cromwell. (1599-1658). Cromwell was born to a family commonly described as a member of the gentry. He had gone through an intense religious experience (possibly as the result of a severe illness) which convinced him that he was a member of the elect, He had risen to fame during the Civil War by infusing Puritan ideals into the Parliamentary army which became known as the New Model Army. Although it was properly called a Protectorate, and Cromwell the Lord Protector, it was in essence a military dictatorship. For historical purposes, the period is called the Interregnum, meaning "between the Kings." The Rump Parliament had prepared a constitution known as the Instrument of Government (1653), which provided for triennial Parliaments, a Council of State, and the office of Lord Protector, held by Cromwell. The Instrument also provided that only Parliament would have the authority to raise taxes. Disputes frequently erupted when Parliament sat for four years, refusing do dissolve itself. Cromwell, determined to bring about a "godly reformation," tore up the Constitution after which he instituted quasi-martial law. He had picked 140 men to serve in a new Parliament, which became known as the "Bare-Bones" Parliament, presumably after one of its members, a leather merchant called "Praise-God Barbon." He kept the standing army in force, and six months later the Barebones Parliament was dissolved and the country divided into twelve military districts, each governed by a major general, who acted through justices of the peace. The Instrument of Government provided for toleration of all Christian religions except Catholicism, an idea which Cromwell supported, but which most Englishmen did not. He also welcomed Jews to immigrate because of their skills. Most Jews had left England 400 years earlier. Yet Cromwell’s Puritan ideals never left him. He never lost his rough edge, and was stubbornly idealistic; easily convincing himself that he was right and therefore should not compromise. He imposed taxes without Parliamentary approval, and dissolved Parliament when it disagreed with him. He insisted that people should lead "godly" lives, and accordingly ordered theaters closed, forbade sports, and censored the press. When a rebellion broke out in Ireland in 1649, Cromwell put it down with merciless savagery. The result of his treatment of the Irish was a deep seated hatred by Irishmen of England and all things English, a sentiment that still exists. The Puritan republic was every bit as oppressive as the monarchy of the Stuarts. He was so unpopular that he began wearing armor under his clothes and took circuitous routes throughout London to foil any assassins who might be stalking him. Cromwell’s regulation of the English economy was typically absolutist. He enforced the Navigation Act of 1651 which required that English goods be transported on English ships. This was a great boost for the British merchant marine and caused a short war with the Dutch. In 1657, a newly elected Parliament produced a new constitution and offered Cromwell the throne. He refused, perhaps because he believed God had spoken to him against the monarchy; but did accept the terms of the "Humble Petition and Advice" by introducing a second house of Parliament, designated the House of Lords, and by the terms of which he could name his own successor. Cromwell demonstrated his gratitude by dissolving the Parliament. He died one year later and was followed by his son, Richard Cromwell. The younger Cromwell was not the man his father was, and served only a short time. At the time of Cromwell’s death a hurricane like storm wreaked havoc on the English countryside. Those who opposed Cromwell said that the storm’s cyclone was the devil, come to claim the soul of the usurper. The Restoration: The military government collapsed in 1658 when Cromwell died. The English people were fed up with military rule, and wanted a restoration of the common law and social stability. They were ready to restore the monarchy, and would not soon re-experiment with a republic. The heir presumptive, Charles, son of Charles I, was living in exile in Holland. However, his return was only accomplished by military force when General George Monck, a former royalist officer with troops still loyal to him marched on London and dissolved Parliament. Charles issued a conciliatory proclamation, and Parliament invited him to assume the throne. He was crowned Charles II on April 23, 1661, eleven years after the execution of his father. Charles II exhibited considerable charm, energy, courage, and a lively sense of humor. He was loyal to those who had been loyal to him during the Interregnum, with the notable exception of his Queen, to whom he was anything but faithful. The colonies of Pennsylvania, Maryland, North and South Carolina were founded when Charles gave generous land grants to those who had supported him. For that reason, these colonies were known as Restoration Colonies. At the time the monarchy was restored, both houses of Parliament were restored also, together with the established Anglican Church, the courts of law, and a system of local government administered through justices of the peace. However the religious issue of the status of Catholics and Puritans and the political issue of the Constitutional position of the King with relation to Parliament remained unresolved. On religious matters, Charles was largely indifferent, although Parliament was not. The Test Act of 1673 stated that those who refused to accept the Eucharist of the Church of England could not vote, hold public office, preach, teach, attend university or even assemble for meetings. Those considered "nonconformists" had to take an oath that they would not try to alter the established order of the church and state in England. However the Act proved largely unenforceable. When William Penn, a Quaker, and a number of his Friends (no pun intended) held a meeting, they were arrested, but a jury refused to convict them. In political matters, Charles was determined "not to set out in his travels again." He planned to get alone with Parliament at any cost. He appointed a council which constituted his major advisors but who were also members of Parliament. These men acted as a liaison between the King and Parliament. These five men became known as the Cabal, after the first letters of their last names: Clifford, Arlington, Buckingham, Ashley-Cooper, and Lauderdale). The Cabal was an ancestor to the present Cabinet system. It gave rise to the concept of royal ministers who answered to the Commons. One of the King’s advisors, Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftsbury, was one of the eight Lord Proprietors who received a royal grant for a colony which they named Carolus, Latin for Charles. The Ashley and Cooper rivers in Charleston, S.C. are named for him. Charles and Parliament had a tacit understanding that he would summon frequent Parliaments and Parliament would grant him sufficient income. Parliament did not keep its end of the deal, and Charles entered into a secret agreement with Louis XIV of France which provided for Louis to give Charles 200,000 pounds annually in exchange for which Charles would relax restrictions on English Catholics, support France in its war with the Dutch, and convert to Catholicism himself. When the deal became public, a tremendous amount of anti-Catholic sentiment arose. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that Charles had no legitimate heir (although he had several bastard children). Next in line upon his death was his brother James, the duke of York, who had publicly acknowledged that he was a Catholic. One Titus Oates actually claimed there was a Jesuit plot to assassinate the King, slaughter all English Protestants and proclaim James King. Oates had made up the entire tale, and Charles knew it, but did not speak up because of his own secret promise to Louis XIV to restore Catholicism in England. Hatred of French absolutism (and Louis XIV in particular) and fear of a permanent Catholic dynasty caused hysteria. The Commons passed an exclusion bill which precluded any Roman Catholic from ascending the throne; however Charles dissolved Parliament quickly, and the bill never became law. The Glorious Revolution of 1688: In the early 1670’s, two factions emerged in Parliament: Members who supported the full prerogatives of the monarchy were known asTories, those who were critical of the King’s policies and who espoused parliamentary supremacy and religious toleration were known as Whigs. In 1679, a number of Whigs tried to make Charles’ illegitimate son the lawful heir. In 1681, Charles attempted to rule without Parliament, as had his father. Several Whigs were charged with plotting to assassinate the King and his brother, and were executed. On his deathbed in 1685, Charles proclaimed himself a Catholic. Charles was in fact succeeded by his brother in 1665 who became James II. In Scotland and western England, a small insurrection developed in favor of Charles’ illegitimate son. The rebellion was crushed, and the pretender was executed. James was as devout in his Catholicism as he was naïve. He showed his true colors almost immediately; and the antiCatholic fears of the multitudes were suddenly and painfully realized. In violation of the Test Act, he appointed Catholics to positions in the army, universities, and local government, and dismissed advisors who were non-Catholic. When a court case was brought to test the validity of his actions, the judges ruled in the King’s favor. He had suspended the law at will, and appeared to reviving the absolutist policies of his father and grandfather. He also issued a declaration of Indulgence, granting religious freedom to all; on its face a noble gesture, but one which did not endear him to Anglicans. Seven bishops of the Church of England petitioned the king that they not be forced to read the declaration of indulgence, as they considered it an illegal act. They were imprisoned in the Tower of London, but acquitted amid great public enthusiasm. The situation reached a boiling point when James second wife became pregnant. James rather rashly predicted the child would be a boy, and a Catholic heir to the throne. The Queen gave birth to a male in June, 1688. The timing of the birth, James’ prediction, and the fact that the only witnesses were Catholic led to rumors that the child was really a surrogate baby. Regardless, the child was next in line to the throne, and a Catholic dynasty appeared inevitable. An influential group of Englishmen, both Tories and Whigs, offered the throne to James’ Protestant daughter by a previous marriage, Mary, and her Dutch husband, William Prince of Orange. William’s supporters flooded England with propaganda in favor of his ascension. William landed with an army, and James took the hint. Popular uprisings appeared all over England, and James supporters defected wholesale. James was in a state of emotional and physical collapse. He with his wife and infant son fled to France, where they lived the remainder of their days. Parliament declared the throne vacant by abdication, and William and Mary were crowned King William III and Mary II. This event became known as the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It forever destroyed the idea of divine rule by an English monarch. A fortuitous event helped William’s cause. When he embarked with 15,000 men, a wind blew his ships to the southwestern coast of England while the same wind kept James’ fleet in port. The fortunate wind was called a "Protestant Wind." By accepting the throne at the invitation of Parliament, William and Mary implicitly recognized the supremacy of Parliament. The revolution established the principal that sovereignty and ultimate power I the state was divided between the monarch and Parliament, and that the King ruled only with the consent of the governed. The College of William and Mary in Virginia, a prestigious institution with a history department second to none was named for William III and Mary II. Parliament quickly passed the English Bill of Rights, the cornerstone of the modern British constitution. Law was to made in Parliament and could not be suspended by the crown. Parliament had to be called at least every three years, and elections to and debates in Parliament were to be free, in the sense that the Crown would not interfere, a principal largely disregarded in the eighteenth century under the Kings George. To ensure an independent Judiciary, the Bill of Rights provided that Judges would hold office "during good behavior." There was to be no standing army in peacetime, and "the subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defense suitable to their conditions and as allowed by Law." (In other words, Catholics could not keep and bear arms—the Protestant majority feared a Catholic rebellion.) Freedom of worship was guaranteed, but importantly, the act provided that the English monarch must be a Protestant. The English philosopher John Locke, personal secretary and physician to Anthony Ashley Cooper, the Earl of Shaftsbury, provided the most profound defense of the Glorious Revolution in his Second Treatise on Civil Government. His First Treatise had discussed the inadvisability of absolute monarchy. In the second Treatise, Locke argued that civil governments were created by the people to protect their life, liberty and property. Every government was charged with protecting the "natural rights" of the people, meaning those rights held by all men because they have the ability to reason. Any government that failed to do so or usurped power to which it was not entitled was tyranny. In the event of a tyrannical ruler, the people have the right to rebel against that government. Locke’s ideas were borrowed from ancient Greek and Roman ideals of government that is that there are natural, or "universal" rights equally held by all people in all societies. These ideas became a powerful influence on Enlightenment thought, and were especially popular in colonial America. By implication, they were also influential in the French Revolution. The Glorious Revolution was NOT a democratic revolution; it placed sovereignty in Parliament, and Parliament only represented the upper classes. The vast majority of English people still had no say in government. However, it did establish a constitutional monarchy, and ushered in a period of aristocratic government which lasted until 1914. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the cabinet system of government developed. The term derived from the small private room in which English rulers consulted with their chief ministers. Under that system, the chief ministers must have seats in the commons and the support of a majority of its members. Over time, the responsibility of the crown in decision making gradually declined. One particular minister, Sir Robert Walpole, who sat on the cabinet from 1721 to 1742, enjoyed the respect of the crown and the Commons. He came to be called the King’s first or "Prime" Minister.