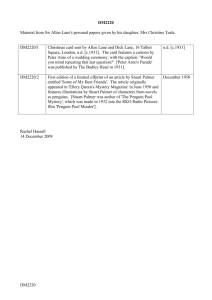

Extended Citations - James Ashley Morrison

advertisement