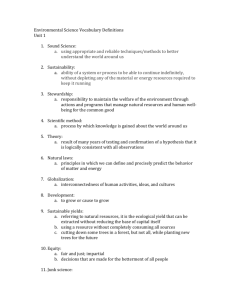

What is Science?-An Introduction to Ecology

advertisement

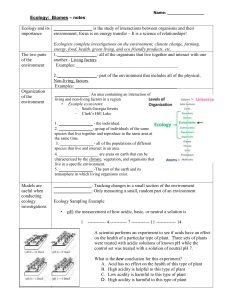

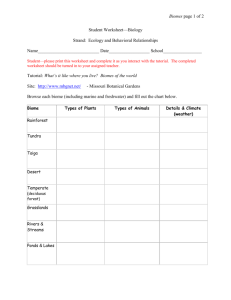

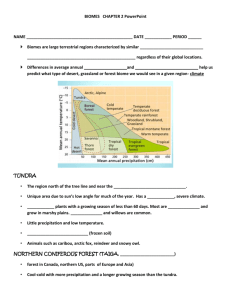

Introduction to Ecology Reading: Freeman, Chapter 50. Ecology is the scientific study of the distribution and abundance of organisms, and their interactions with the environment. The word “ecology” comes from the Greek words “oikos”, meaning house, and “logos”, to study. What do we mean by “scientific study”? There are hundreds of different sciences; each employs different techniques and has its own methods and standards of evidence. In one form or another, the “scientific study” of every subject uses the hypotheticodeductive approach. This approach is rather new historically, tracing its roots back to the European enlightenment of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Essentially, it goes something like this A scientist, or group of scientists, becomes interested in explaining one aspect of how the natural world works. (This comes easily for scientists, as well as most people, people are curious...) Both intentionally and unintentionally, scientists conduct observations. (Some observations may be commonsense or centuries old (i.e., the tides), others may require specialized experience (variation in scutellar hair number on different strains of Drosophila) A hypothesis is constructed based on all the pertinent observations. A hypothesis is a suggested explanation for a phenomena, based upon a conceptual “working model” of how a system works. Good hypotheses generate predictions that can be tested. In experimental sciences, experiments are set up to test the hypothesis. – In the historical sciences, additional evidence is gathered in the place of experiments (although not nearly as incisive, some areas do not easily lend themselves to experiments (i.e., stellar astronomy)). If the predictions of the hypothesis are not borne out, the hypothesis is falsified. Interestingly, a hypothesis cannot be proven true by an experiment, even when it correctly predicts the outcome. This is because an infinite number of hypotheses can usually be generated that predict the same outcome. The strongest hypotheses are usually accepted as true if multiple experiments fail to falsify them. These hypotheses, and their underlying models, form scientific paradigms which may last for centuries or longer. Scientific paradigms are explanations for how the world works, they inspire future research, but also limit its direction to certain avenues. Example-Zonosemata wing markings. Observation-Zonosemata flies have dark bands on their wings. They wave them up and down when disturbed. Based on the prevailing scientific paradigm in biology (Darwinism)-Erick Greene asked “How could the behavior evolve by natural selection?” 3 hypotheses Hypothesis 1-Wing patterns and displays evolved by sexual selection. (courtship displays such as this are common in flies) Hypothesis 2-Wing patterns and displays evolved to scare predators by “mimicking” a jumping spider. (mimicry is a common defense in the animal kingdom) Hypothesis 3-Displays evolved to deter predation by jumping spiders themselves. Experiment He created five experimental groups 1-Untreated controls 2-Zonosemata with own wings re-glued 3-Zonosemata with housefly wings 4-Houseflies with Zonosemata wings 5-Untreated houselfies He subjected flies from each treatment to starved jumping spiders and other predators, conducted 20 trials, measured number of times spider or other predator attacks v.s. retreats. Questions-Why group 2? Why not just 1 trial? Predictions Hypothesis 1-All flies should be attacked. Hypothesis 2-Jumping spiders should attack all groups. Other predators should attack groups 3-5, but leave 1 and 2 alone. Hypothesis 3-Other predators will attack all groups. Jumping spiders will avoid groups 1 and 2 but attack everything else. What does this data suggest? # of kills out of 20 trials Jumping spider Anole Group 1 4 19 Group 2 4 20 Group 3 20 19 Group 4 20 20 Group 5 20 19 Ecology has a long history as a historical science, and is becoming an experimental science. At the moment, ecology lacks a scientific paradigm because many of its underlying ideas have not been sufficiently tested or have crumbled under the weight of new experiments. This makes ecology an exciting field, because new discoveries can have an enormous impact Based Upon the Questions they Choose to Ask, Ecologists May Work at One or More of Several Different Levels of Organization: Individuals Populations Communities Ecosystems Individuals are single, discrete organisms. ...In some cases, it is easy to define an individual organism, i.e., mice and people. In other cases, the distinction between individuals is arbitrary or nonexistent. A stand of aspen trees looks like many individuals above the ground, but below ground they are all interconnected. A single fungus mycellium may occupy tens of square kilometers beneath the surface of a forest. For example, a scientist might ask a question about how a cave cricket finds its way in and out of the entrance of a cave every time it forages. This is called organismal ecology. Populations are groups of organisms of the same species living in the same place. Individuals of the same population interact with one another: most interaction among members of a given species occurs within a population They may compete for resources and mates, they may combine alleles via sexual reproduction. Examples of populations include: ...a herd of wildabeast ...all the bullhead catfish living in a midwestern lake …all of the tropicbirds nesting on a single oceanic island ….the E. coli population in a single person’s gut Population ecologists ask questions at this level. Very frequently, these questions concern abundance, density, population growth, and limits to growth. For instance, a population ecologist might study the extent to which the number of available nest sites affects the maximum number of tropicbirds an island can sustain. Communities are assemblages of populations of different species living in the same place Different species have different “functions” in a biological community. – For instance, some are decomposers, some are producers, etc. – Some species within the community may interact to a great extent, while interaction between other species may be virtually nonexistent. The extent to which biological communities are tightly knit systems, or opportunistic assemblages, is debated. A community ecologist might ask questions about the extent to which parasitic wasps control outbreaks of pine sawflies, and whether the presence of parasitoids is necessary for the presence of pine trees. www.hort.wisc.edu/.../insects/eps/eps.htm Ecosystems Ecosystems are interacting assemblages of living things living in a particular area, accounting also for the nonliving components, such as light, water, nutrients, soil, and seasonality, that are important to life. – Ecosystems are nested within other ecosystems. An ecosystems ecologist studying caves might ask questions about the role of bat guano entering the caves, and the extent to which nutrients and energy brought in by the bats from outside, via their guano, support the nonphotosynthetic ecosystem in the cave. What is a Species? The concept of a species is fundamental to biology, yet biologists disagree on exactly what constitutes a species. There are several different, working definitions of a “species” Different branches of biology use different working definitions because they have access to different information or because of fundamental differences in the biology of the organism in question. “Biological Species Concept” “A species is a group of actually or potentially interbreeding organisms that can mate and produce fertile offspring” –Ernst Mayer This definition is very interesting from an evolutionary perspective. It defines species as “real”, objective entities, defined by the limits of gene exchange Morphological Species Concept “Species are Groups of Organisms that Share Certain Morphological or Biochemical Traits” Some species do not reproduce sexually, some are known only from fossils. This definition is the working definition used by biologists that cannot, or should not, use the “Biological Species Concept” It is more subjective Phylogenetic Species Concept A species is a discrete lineage, propagated, ancestor to descendent through time, which is recognizably different from other such lineages and shares a distinct evolutionary history. It defines a species by its relationship to other species. Example of an ecological hypothesis test Robert Marquis and Chris Whelan studied the role of birds in limiting the density of herbivorous insects. They observed that deciduous forests harbor hundreds of species of herbivorous insects, yet only a small proportion of total leaf area is eaten every year. Many species of birds are insectivores, but spiders, parasitic wasps, and fungal infections also attack insects. Are birds an important factor in controlling herbivores? Experimental Treatment-Multiple trees (replication is important) are enclosed in cages to exclude birds but not insects. Control Treatments– ”Control trees” paired with the excluded trees control for environmental variation. – Incomplete cages-control for the presence of the cage. Data Collected– % of leaf area eaten – density of herbivorous insects Prediction-if birds are an important agent of insect control, both variables should be higher in exclusion cages Result Caged trees had 70% more insects than controls, and caged trees had an increased percentage of missing leaf area (35%) relative to control trees (22%) Conclusion-birds are an important potential agent of herbivore control. Other studies– One of the most important attributes of a good experiment is that its results be reproducible. – This is a problem in ecology, because conditions in “the field” vary from year to year and place to place-it is almost never possible to reproduce a field experiment exactly. – Exclusion experiments of this type have been done many times, with different results Ecological Time Scales Ecological processes may occur over time scales ranging from days to millennia. The ecological time scale is shorter than the evolutionary time scale, but there is some overlap-populations evolve over time, and this can affect the composition of communities and functioning of ecosystems. What we see today might reflect events that happened long ago by our standards. – Example-colonization of North American forests following glaciation-a continuing process Alpine populations of tundra communities persist at high elevations Chicago was under ice 15,000 years ago-“Lake Chicago” existed here thereafter, gradually growing as the glacier melted-it drained out the Mississippi. – As a result, The community of Great Lakes fish species resembles that of the Mississippi river, rather than the Atlantic ocean. Deciduous trees have replaced Pine and Juniper as warm conditions persisted– Different species have colonized at different rates. – A relict population of Pines is still present at Indiana Dunes national Lakeshore. Climate vs. Weather Weather is the particular set of abiotic conditions, such as rainfall, sunlight, temperature, and humidity, affecting a particular area at a particular time. Climate is the overall pattern of weather in that area. Weather changes daily, climate changes over decades, hundreds, or thousands of years Biomes are broad assemblages of plant and animal communities generally defined by the dominant vegetation. This is an old concept in ecology, first established by the terrestrial plant ecologists F.E. Clements and V.E. Shelford. Biomes paint a broad swath of an area based upon what the dominant vegetation looks like. A recent approach has been to be more specific by naming Ecoregions. Ecoregions are major ecosystems that result from predictable patterns of climate as influenced by latitude, global position, and climate. Terrestrial Biomes (some scientists count them differently) Tundra Taiga or Coniferous Forests Desert Chaparral Grasslands – Savannah Temperate Deciduous Forests Tropical Rain Forests – Tropical Dry Forests Terrestrial biomes have characteristic vegetation determined by the amount and timing of water, the amount of available sunlight, and by temperature. Vegetation provides a spatial structure to terrestrial biomes. Spatial structure creates microenvironments important to various different organisms Biomes differ greatly in their productivity and their biodiversity Major Physical Factors influencing terrestrial biomes Rainfall, and its timing Sunlight Disturbance warm wet areas favor rainforests Intermediate areas can be either grassland or forest, depending upon other factors Tundra receives very little precipitation, deserts range from hot to cold Tundra Tundra is characterized by the lack of trees, the dominant vegetation is lichens, annual grasses, and, in some places, very specially adapted shrubs and woody plants. Tundra occurs in polar climates and at high elevations, where the growing season is very short. Nearly all precipitation falls as snow. Plants and insects flourish during the short growing season. Taiga or Coniferous Forest Cone-bearing trees such as pine, spruce, and fir dominate. most are dominated by one or a few species This biome is very common, covering huge areas at high latitudes or high elevations The cool to warm summers are the growing season Plants are dormant during the winter, when temperatures drop far too low for photosynthesis. Often, much of the precipitation falls as snow. Snow melt releases a great deal of water into the communities that make up the taiga Desert Low rainfall, generally less than 30cm per year, characterizes a desert Many deserts are very hot (at least during the day), but some, such as the Great Basin and the Gobi Desert, are cold most of the year. The dry environment often causes a dramatic difference in temperature between day and night Grasses are usually found when water is available (they are dormant underground, or as seeds, when there is no water). Succulents, such as cacti and euphorbs, and shrubs with specialized water-saving adaptations, are present. Trees are uncommon or totally absent. Chaparral: Cool, rainy winters and dry summers Dense, spiny, evergreen shrubs dominate Seasonal fires Most of the plants are fire-adapted. Many species can only reproduce via periodic fires This biome has high biodiversity, with a great deal of endemism. Endemism is when species are found in one place only This biome is rather uncommon, being confined to relatively few locations with a Mediterranean climate, California, Costal South America, South Africa, the Mediterranean, and Western Australia Grasslands Grasses and forbs dominate. Fire and grazing prevent the establishment of shrubs and trees Moderate to low rainfall and a wide range of temperatures permit grasslands Seasonal drought, occasional fires, and grazing by herbivores prevent the establishment of trees as the dominant vegetation Grasslands are a widespread biome; examples include the Prairies of North America, the Steppes of Asia, the Pampas of Argentina, the Veldts of South Africa, and the Puszta of Hungary. Savannah Savannah is grassland mixed with scattered trees (sometimes it is considered its own biome.). Temperate Deciduous Forests Moderate rainfall and mild to warm summers with cool to cold winters. Occur at mid-latitudes, where moisture is sufficient to support the growth of large trees Winters are cold enough to prohibit photosynthesis, and most organisms go dormant or hibernate over the winter Dense stands of deciduous trees predominate Trees tend to have distinct vertical layers; including one or two strata of trees and an understory of shrubs Tropical Rain Forests The most productive biome on the planet, also harbors the most biodiversity. Most are located near the equator, where temperatures are warm and relatively constant year round Plants are broad-leafed evergreen trees, shrubs, woody vines, and epiphytes. epiphytes-plants that live on other plants, usually trees. Examples include orchids and mistletoe High rainfall-usually with a pronounced rainy season and dry season. Competition for light is intense. Pronounced stratification with several layers of trees. Tropical Dry Forests tend to occur in lowland areas, where the distinction between the wet season and the dry season can be very pronounced deciduous trees, thorny shrubs, and succulents are very common Though they are useful as a first sketch of what is in an area, biomes are a rough sketch. A grassland in South Dakota is very different from a grassland in South Africa. Ecoregions are more specific, accounting for soil, climate, climate, vegetation, and history. It is a heirachial scheme. Domain is the broadest – within domains are Divisions – within divisions are Provinces Aquatic communities are determined by the availability of sunlight and nutrients The term “biome” is not generally applied to aquatic environments, though the oceans have been broken into oceanic regions. Like terrestrial areas, aquatic environments include huge volumes of habitat defined by a few basic factors – The water column itself provides spatial structure. Within a given oceanic region, communities are stratified spatially. Open Ocean Pelagic Zone: Light penetrates the top few meters Except in areas of upwelling, nutrient concentrations are generally low, because the remains of dead organisms sink to the bottom of the ocean. All organisms are floating or free-swimming “nekton”. The major producers are photosynthetic algae. Abyssal Zone: Nutrients reach this zone by falling from above. Light is absent. This zone supports a wide variety of specially-adapted organisms Wetlands Wetlands are areas covered in water that support aquatic plants They range from periodically flooded regions, to soil that is saturated with water during the growing season, to permanently flooded areas Typical Wetlands Estuaries-occur at the mouths of rivers Swamps-flooded areas dominated by trees Marshes-flooded areas dominated by sedges and grasses Bogs and Fens-have distinctive vegetation because their soil is either very alkali (fens), or very acidic (bogs). For most, but not all groups of organisms, biodiversity increases from the poles to the tropics This is called a latitudinal gradient in species diversity Reason for this pattern is a mystery in ecology. Four hypotheses-none is sufficient to explain it alone. 1) greater productivity in tropics 2) history 3) complexity of habitats 4) less disturbance History affects what species live in an area as well. In the broadest sense, the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace broke the world into several “biogeographic realms”. Which species occur in each region are determined by historical and evolutionary factors.