Learner Autobiography - Emily Sirotkin's Portfolio

advertisement

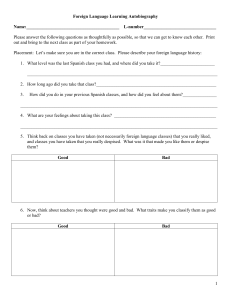

Sirotkin 1 Emily Sirotkin 12/17/10 TEAC 452R Learner Autobiography For as long as I can remember, my parents knew I would be a teacher. It started when I was three years old; I would line up my stuffed animals and teach them stories and songs before I went to bed. Then a couple years later, my younger sister became my new pupil. I enjoyed teaching her, especially because she learned more quickly and was a significant improvement to my inanimate toys. When I came home from school, one of my favorite games to play was imaginary school. I would always be the teacher and I would staple papers together for notebooks, collect some important books, and create worksheets for her to complete. Before she was in kindergarten, I was teaching her letters, numbers, basic math, and interesting information that I had learned at school. By the time I reached third grade and tried to teach long division, she finally demanded an end to my school. I remember she was angry and said, “I get so bored at school – you’ve already taught me everything!” Fortunately, by upper elementary school, I started to help out with the younger grades and was paired with a first grade student as his tutor, which was a more appreciated outlet for my teaching efforts. I think partly what drew my interest in teaching was my strong desire to help other people. I usually understood the classroom content relatively quickly, and I enjoyed explaining it to others. Through enjoying these informal teaching experiences, in high school I became a teacher in several different capacities. I became a tutor at an after school center for elementary school students, mentored a girl through Big Brothers Big Sisters, and tutored students struggling with Spanish at my high school. One elementary school contacted my Spanish teacher to find Sirotkin 2 help with their after school Spanish program. I loved being able to play games and communicate with the students in Spanish; the kids learned so quickly and enjoyed the activities, so their enthusiasm became contagious. The students were learning very quickly in an environment with a low affective filter. According to Krashen’s Input Hypothesis, language learning is best when the students can learn with a low affective filter, in an environment where they don’t have a paralyzing fear of making mistakes. In my practicum at Lincoln High this semester, I have found this principle to be true. The students learned very quickly when there was a low affective filter. At the beginning of the semester, the students were still getting to know each other, but as the semester progressed, we built a strong classroom community where the students felt comfortable communicating with each other. This low affective filter affected everything we did, because the students were already more excited and willing to participate in each learning activity. Despite these fun memories, throughout most of high school I had never really considered becoming a Spanish teacher, because it was a subject that didn’t naturally come as easily to me. I felt as though I learned really slowly compared to other students. Vocabulary lists never stuck in my memory. I couldn’t seem to pronounce anything correctly and presentations in Spanish made me extremely nervous. Grammar rules especially confused me because I could never remember the names of the different tenses. Now I realize that this is because our Spanish lessons were not taught in context. Krashen’s Input Hypothesis also discusses how learning should be acquired through real communication and should follow a natural order. The vocabulary we learned was isolated from a real world context, which made it much more difficult to learn. Grammar rules were taught through explicit instruction, which didn’t leave any room for higher-level thinking or implicit analysis. This was extremely evident in the Sirotkin 3 classroom this semester. During my first week of observation, the teacher handed out a vocabulary list and gave it to the students. The list was never revisited until the quiz on Friday. Most of the students came into class, realized there was a quiz, and tried to “memorize” the list as quickly as they could. Most of them did fine on the quiz, but they didn’t have any long-term retention of the words. Later in the semester, we used activities to teach the grammar. One time I had the students read articles about Christopher Columbus in small groups. Then each group prepared a list of the vocabulary words that they would need for the class debate. I compiled all of the words that they had chosen and we used them in class for the next few days to debate whether Christopher Columbus should be thought of as a hero or a villain. The students loved it! Every student was engaged and they all participated in the debate. The day of the quiz, they didn’t have to cram-study the vocabulary because they already knew how to use it in a real-world context. My passion for Spanish came from outside of the classroom where I had authentic input and I was able to practice using the target language. From my observations this semester, very few teachers use the target language very often in the classroom, especially in beginning-level classes. Even in some intermediate (Spanish 2 and 3) classrooms that I saw, the teacher greeted the students with “Hola” but used mostly English to give instructions. The students filled out worksheets, but talked in English. In this type of learning environment where the target language isn’t a means for authentic communication, it was easy to see the students’ disinterest and frustration with the language. Fortunately, the summer after my junior year of high school, I traveled to Dominican Republic with my youth group for two weeks. I was so excited when I got off the plane because I was suddenly surrounded by a new, exciting, and beautiful culture. I saw huge, colorful Sirotkin 4 advertisements – in Spanish; listened to upbeat music on the radio – in Spanish; overheard friendly conversations – in Spanish. Suddenly I realized that Spanish was not just part of my course requirements to get a high school diploma. When I saw the culture and real use of Spanish in an everyday context, I realized that the language was not simply rules or lists of words, but a way to communicate and connect with other people around the world. Instead I began to view Spanish as a beautiful language, a new avenue for communication, and as part of the Hispanic culture. In one observation, I did notice the extreme difference in the class atmosphere and student engagement. The teacher communicated completely in Spanish, and the students were aware of the expectation that only Spanish was spoken in the classroom. When I walked in, the students greeted me in L2 and asked me questions in Spanish. They were engaged the entire time in meaningful communicative activities. It was awesome and encouraging to see the difference in motivation and interest when the teacher pushed the students really communicate in Spanish. The summer before my senior year of high school, my church began to partner with a Hispanic church to offer free English lessons. We didn’t have any certified teachers, but three other adults and I went. Each of us received a binder full of textbook materials and lessons, and then we were left on our own to determine the class format the next three hours. I was the only one with any Spanish experience, and many of the students were adults who had come to America only a couple months, or even days, earlier. We tried to follow the curriculum, but by the third week the lesson was about zoo animals and farm animals. For adults who are concerned with basic necessities, getting a job, and helping their children, the topics didn’t seem relevant. The lessons that we were given were not meaningful or authentic for the audience of students. We decided to toss out the lessons and create our own based on topics the students chose – going Sirotkin 5 to the doctor, job applications, and grocery store basics. When the students were able to affect the classroom and bring their own questions, background knowledge, and experience, they were much more motivated to learn the material. Using real-life context made the information relevant to these adult learners. Although it was not the most organized classroom, I loved it. After that semester, I decided that I would love to teach Spanish and English as a Second Language. In my AP Spanish class, we had class discussions in Spanish. The topics in our textbook seemed outdated and unrelated, so my teacher, Señora DeWispelare, would assign television shows to watch before our class discussions. Sometimes we would watch Survivor: Amazon or Grey’s Anatomy; other times we would discuss the recent Husker football game or our favorite restaurants. We prepared ahead of time by writing down ideas to discuss and also looking up key vocabulary or phrases that we wanted to use in the discussion. I think that these words and phrases taught me more than most of my previous vocabulary lists, because I learned them in a relevant and meaningful context. Lots of times I would cram study time for the vocabulary list right before the quiz and then quickly forget the words by the next day or two. However, the words that I wanted to use in the discussion were important to me, so I had more motivation to learn them. Then, since we actually used the words several times throughout the discussion, I would be more likely to remember them later. Through meaningful interaction and output, the concepts and vocabulary were reinforced during class. After one outstanding classroom observation, I asked the teacher more about the types of activities that she plans in her classroom. She talked about the importance of having students communicate with ideas that they are interested in. One idea she mentioned is to have the students write down topics that they want to discuss. All of their ideas are put into a bowl and she draws one Sirotkin 6 idea at the beginning of the class period for them to talk about. Often the students write down songs, movies, and sports. The best part is that the students are already interested in the topic and want to communicate. By bringing the students’ own opinions and ideas into the classroom, the teacher created meaningful communication opportunities. As I mentioned before, learning Spanish was not an easy process for me. I think that the best way to learn a language is to become completely immersed in it. The two weeks I spent in the Dominican Republic taught me more than I had learned in my first three years of Spanish in the classroom. My Spanish II teacher, Señora Lenz, demanded that we only speak Spanish in her classroom, and she did the same. Even when we were learning difficult or confusing concepts, she taught us completely in Spanish. This increased our interest because we had to use context clues, gestures, and higher-level reasoning to figure out what others were saying. Sometimes she would have to explain it to us three or four times using different words each time. When I first started giving instructions completely in Spanish, the students looked very confused. The very first activity I explained was a five-minute writing prompt. The words were all very simple, but the students were used to getting directions in Spanish and English. The blank faces of the entire classroom stared at me. I explained the directions again and then started a timer. Two minutes into writing time, I realized that they still didn’t fully understand. I explained the directions one more time in Spanish and then reset the timer. By the third time, they realized that I wasn’t going to speak in English, and I could see them try a little harder to understand. The activity was short and it went alright, but in the future, students learned that the expectations were much higher and they paid attention much more closely when we gave instructions. Sirotkin 7 My experiences overseas in Spanish speaking countries have been amazing and very different than my formal classroom experience. I’ve taken two trips to Dominican Republic and I spent a summer in Mexico City. Instead of filling out worksheets or completing verb conjugations, I overheard conversations. I had to use gestures to communicate and talk around the vocabulary that I didn’t know. Suddenly it became much more important to try to speak Spanish, because it was all around me. I also remember taking a day trip to Haiti, where the national languages are French and Creole. This immersion was even more staggering because I didn’t know any of the words being spoken around me. Again, it was through gestures and nonverbal communication that I began to learn some basic words to communicate with the children at the orphanage. These are important tools that teachers can explain and use in the classroom to help students use learning strategies with language learning. A teacher that I observed had explained the concept of circumlocution and told her students to “habla alrededor” or “talk around” the concepts that they were trying to say. For part of the class period, she wouldn’t let her students use dictionaries to communicate. This was difficult for some students, but they learned that they could use their prior knowledge to really communicate! I think that in a formal classroom setting, I often rely on finding the “right answers” and trying to complete the blanks on the worksheet. Also, there are several aids, such as dictionaries, posters, and answer keys that make classroom learning much different. In a complete immersion experience, often there are no external aids to rely on. For me, another major difference is the urgency of learning the language. In high school, I knew that the bell would ring at the end of the period and then I was free to go into the hallway and speak English with my friends, go home and write my papers in English, and interact with English-speakers in the community. Being Sirotkin 8 overseas, there really aren’t any other options than trying to figure out how to best communicate with the skills that you have, which makes the input more meaningful. In a study abroad experience, I think that my language strategies are different than in the classroom. One important difference for me is risk-taking. When I had no other option than speaking in Spanish, I was willing to take more risks because I wanted to be able to communicate. I had to use circumlocution, gestures, or other strategies to communicate. Several students in my Spanish IB classroom relied on dictionaries to look up every word before they would say an answer aloud or write it down on their paper. Sometimes that was great because the students were learning new words that they really wanted to use. However, sometimes we forced the students to try to communicate without using the dictionary and to use their current knowledge. Often I would say to them (in Spanish), “Pretend that we are in Mexico and you want to tell me the answer. What would you say, since you don’t have a dictionary? How would you tell me?” They were almost always successful at communicating their point, and they began to realize that they could use strategies like circumlocution to communicate. I saw this increase their motivation to really learn Spanish because they saw that there was a meaningful result, not just a passing grade on their quiz or test. Through my experiences learning a foreign language myself, as well as my observations while helping students who are learning English as a second language, I have developed some beliefs about language learning and teaching. I believe that every student should be treated fairly and equally, but this does not mean that everyone learns the same way. I want to use a variety of teaching methods in order to reach students with different learning styles. For example, using multiple intelligences in the classroom can be an important way to help students learn information in a way that is best for them. I want to give multiple opportunities for students to Sirotkin 9 learn the information in a variety of activities. For visual students, it may be helpful to have pictures and maps to go along with the material. For kinesthetic learners, it may be more helpful to actually do actions for the words, such as with the TPR method. For logical-mathematical learners, I could provide an outline or clear structure. I think that it is really important as a teacher to keep the variety of student backgrounds and intelligences in mind. This semester I did a couple of lessons on multiple intelligences. I started by giving my students a multiple intelligences inventory. There was a wide variety of learners in the classroom and I realized that they didn’t know how to apply this to their own Spanish learning. Since we were starting our travel unit, we decided to introduce important words using different intelligences. First I divided them into mixed groups to do a review activity of airport vocabulary. Next we split into similar learning styles to learn new vocabulary. Knowing the importance of learning vocabulary in context, I created meaningful activities to incorporate higher-level thinking. For example, the verbal-linguistic group could write a story, newspaper headlines, or debate incorporating several new vocabulary words. The logicalmathematical group could make a time-line of a vacation, write analogies, or create a word map. The visual-spatial group drew the words, created symbols to remember concepts, or created a graphic organizer to visualize the words. The kinesthetic learners created motions, did charades, or acted out a drama with the words. The students really enjoyed these activities because they could work from their own strengths and they had a variety of ways to learn creatively. When I asked the students, many of them had never tried to study using any of these ideas and in the past they had only done rote memorization of the vocabulary. I explained that research says that they will learn better when they use Spanish in context (instead of a vocabulary list) they were much more interested in the activities. Sirotkin 10 After doing these activities, the students were very well-prepared to use the vocabulary for the rest of the unit’s activities. Teachers not only present information, but they are in the classroom to facilitate learning, which can take a variety of forms. This means that teachers will need to initiate classroom discussion, small group projects, and individual activities. Teacher-facilitated learning is important, because the classroom should be learner-centered. The goal is for the students to learn the information rather than just have the teacher tell them. Students will only remember 10% of what they read and 20% of what they hear; however, they will remember 90% of what they actually do. This means that teachers are extremely important in the classroom to guide and facilitate learning so that students can discover language and use it in real communication. I definitely used this principle during my practicum. I rarely lectured because I had observed other classrooms where students had disengaged – either actively doing other homework and/or talking with their friends, or simply zoned out and not paying attention to class. Instead, I had a wonderful practicum experience. I saw that when the students were seeking to find answers or working together to create a project, they were very engaged. George is one student who I noticed from the very first week of observing my practicum teacher. He never spoke during class and didn’t appear to be paying attention during class. Another student, Diana, is a heritage Spanish speaker, yet I noticed that she is extremely shy and rarely spoke up as well. I wanted to find a way for all of the students to have a chance to learn during class, and we discovered that using pair work was one of the best ways. In pair work, every person is needed. Another important factor is that I never just gave the students an assignment and then graded papers or sat at my desk. It was really important to continually circulate through the room in order to monitor progress, Sirotkin 11 answer questions, resolve any confusion, and show the students that I care about their progress. I believe that language should not be taught separately from the rich history and society that contribute to the larger culture behind the language. Spanish language came alive for me when I began to see it in real life, hear it spoken by real people, and have real conversations in Spanish. Although study abroad experience cannot be exactly replicated in the classroom, I think that students can still gain an appreciation of culture and history through authentic culture lessons, bringing in realia, use of multimedia, and engaging, interactive lessons. Some activities that Kathryn and I created and implemented this semester in practicum included a travel vacation to Barcelona. The students used a budget sheet to plan their week-long vacation, filled with activities that they found online in Barcelona. The students really enjoyed it, and they mentioned at the end of the semester that it was one of their favorite lessons. They were able to use real culture, real pricing, real plane tickets, and simulate their own winter break destination vacation. Spoken and written language cannot be separated from the cultural heritage that accompanies the people who use it. I want to continue to gain an appreciation for Spanish culture and allow my students to explore Spanish culture as well. It is very important for students to realize that there is more to Spanish culture than fiestas and siestas. Rather, there is both macro-culture, which involves music, art, literature, and history, as well as micro-culture, which involves everyday life. Many high school students don’t have an awareness of the variety of cultural practices and customs, but the Spanish language can provide a unique opportunity to learn about Spanish culture. Another activity that we used this semester was the song “Jueves” by La Oreja de Van Gogh. The song talks about a guy and a girl who notice each other on the train each day. But this fateful song ends with the terrorist attacks in Spain Sirotkin 12 that happened March 11 when trains were bombed and nearly 200 people died. The students learned more about Spanish culture and history, as well as enjoying a famous song and musical group. I think that this was a wonderful activity and it is something that I definitely want to use in the future. When we watched the music video, the students were mesmerized as they watched real video footage unfold while we listened to the song. These activities were awesome for learning about culture in a fun and meaningful way. I think that teachers also need to be interested and passionate about the subject area. Teachers are role models and set the pace for the classroom. If the teacher is involved and engaged in the topic, then their students will be more curious and interested as well. If teachers set the pace with a positive attitude and a good learning environment, the affective filter will be lower which will increase students’ overall learning. The most effective teacher I had was Mr. Heys for my AP United States History class. Mr. Heys is brilliant, both as a teacher and as a history buff. He has a passion for history and gets excited about the information that he teaches. That passion is matched only when he sees history come alive for his students. We never knew what to expect going into class; every day was new and different. His passion increased our own motivation and lowered the affective filter because we were excited to enter an open learning environment without the pressure of performing for grades. I tried to implement this in my classroom each day. When we presented activities to the class, I never heard any complaints but I really would always try to be interested and excited in what we were doing in class every day. If I thought that I would be bored with an activity, then I wouldn’t use it. When I looked at the textbook activities and reading selections, I was not interested at all. Instead I would use current events articles or bring in songs and activities that I found interesting. When I could be passionate about the activity, then I was ready to present it to Sirotkin 13 the class. I asked teachers for their best teaching advice. One teacher who had been teaching Spanish for several years told me that his advice is to keep the activities new and exciting – don’t just do the same thing every day, semester, or year. I think that his advice is really important because when the teacher is excited for the lesson, the students are much more likely to be interested as well. Even if it was another day of lecture, Mr. Heys never just talked to us for the entire hour and a half. He always had a list on the board with what we would learn that day, but it wasn’t a traditional list. Instead he would draw pictures or symbols to illustrate the main points that we would learn. Often we would come into class puzzled by the pictures and then ponder how it would link to the textbook reading. This increased our interest because we wouldn’t know what to expect, but he left ambiguity to pique our interest. Often I used visual symbols instead of words for the daily schedule. For example, a drawing with music notes meant that we would analyze song lyrics, or a picture frame meant that we would do a gallery walk. The students would usually ask me what it meant or what we would be doing that day, and I could tell that they were more excited because they knew something interesting was planned. Other times I would end the day with something exciting for them to look forward to the next morning. One day I told them that the next day would be a writing day, and the students all groaned. The next time we were going to have a writing day, instead I told them (in Spanish) to bring their imagination the next day because we were going to be extra creative. They asked what we would be doing and seemed excited. I gave them creative writing options where they could write a dialogue of a cooking show, speech for a famous athlete, or narrating a sports event. We avoided the groans and sighs, and the students were engaged and wrote very creative stories. Sirotkin 14 Mr. Heys was always be extremely prepared, and often incorporated visuals into the lesson, including movies, photos, word webs, and drawings. Having visuals along with the lecture provided dual coding, which helped us to process the information more deeply and remember it better long-term. I saw that dual coding benefitted the students. For the first story that we read, the students did a jigsaw activity to analyze just one part of the story. They drew storyboard pictures for their section and then shared them with their home group. This helped students to retell and really understand what happened in the story. Overall, I have had an outstanding experience with my practicum this semester. I loved the students and I thought it was really fun that I could try out new lesson plans every day. If something didn’t work, I could analyze why and then change it for the next day. I hope to continue to implement these important teacher beliefs and learning theories in my future classes. And I’m excited to continue to learn and grow from my student teaching classes!