AbSciCon (2006)

advertisement

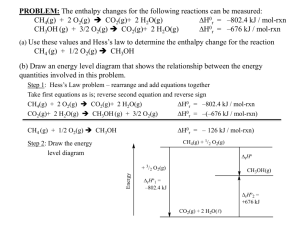

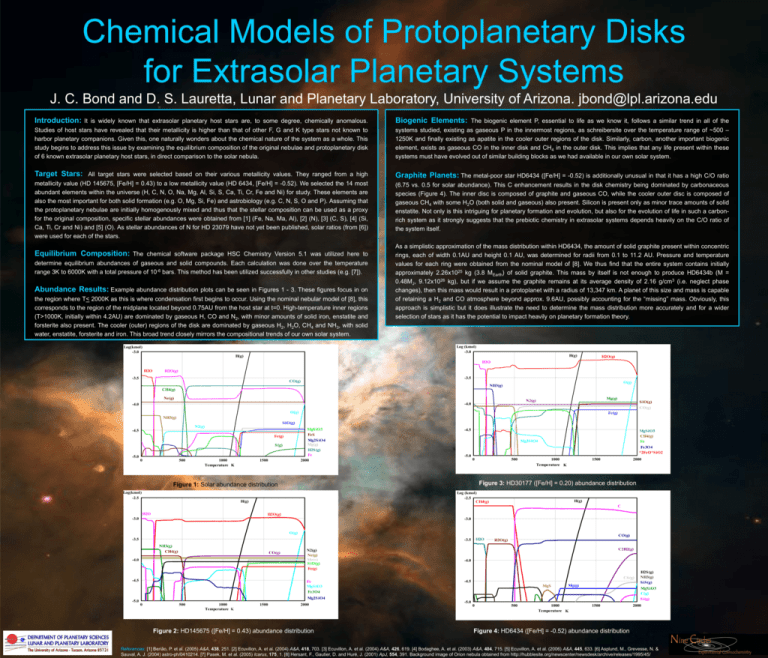

Chemical Models of Protoplanetary Disks for Extrasolar Planetary Systems J. C. Bond and D. S. Lauretta, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona. jbond@lpl.arizona.edu Introduction: It is widely known that extrasolar planetary host stars are, to some degree, chemically anomalous. Biogenic Elements: The biogenic element P, essential to life as we know it, follows a similar trend in all of the Studies of host stars have revealed that their metallicity is higher than that of other F, G and K type stars not known to harbor planetary companions. Given this, one naturally wonders about the chemical nature of the system as a whole. This study begins to address this issue by examining the equilibrium composition of the original nebulae and protoplanetary disk of 6 known extrasolar planetary host stars, in direct comparison to the solar nebula. systems studied, existing as gaseous P in the innermost regions, as schreibersite over the temperature range of ~500 – 1250K and finally existing as apatite in the cooler outer regions of the disk. Similarly, carbon, another important biogenic element, exists as gaseous CO in the inner disk and CH4 in the outer disk. This implies that any life present within these systems must have evolved out of similar building blocks as we had available in our own solar system. Target Stars: All target stars were selected based on their various metallicity values. They ranged from a high Graphite Planets: The metal-poor star HD6434 ([Fe/H] = -0.52) is additionally unusual in that it has a high C/O ratio metallicity value (HD 145675, [Fe/H] = 0.43) to a low metallicity value (HD 6434, [Fe/H] = -0.52). We selected the 14 most abundant elements within the universe (H, C, N, O, Na, Mg, Al, Si, S, Ca, Ti, Cr, Fe and Ni) for study. These elements are also the most important for both solid formation (e.g. O, Mg, Si, Fe) and astrobiology (e.g. C, N, S, O and P). Assuming that the protoplanetary nebulae are initially homogenously mixed and thus that the stellar composition can be used as a proxy for the original composition, specific stellar abundances were obtained from [1] (Fe, Na, Ma, Al), [2] (N), [3] (C, S), [4] (Si, Ca, Ti, Cr and Ni) and [5] (O). As stellar abundances of N for HD 23079 have not yet been published, solar ratios (from [6]) were used for each of the stars. (6.75 vs. 0.5 for solar abundance). This C enhancement results in the disk chemistry being dominated by carbonaceous species (Figure 4). The inner disc is composed of graphite and gaseous CO, while the cooler outer disc is composed of gaseous CH4 with some H2O (both solid and gaseous) also present. Silicon is present only as minor trace amounts of solid enstatite. Not only is this intriguing for planetary formation and evolution, but also for the evolution of life in such a carbonrich system as it strongly suggests that the prebiotic chemistry in extrasolar systems depends heavily on the C/O ratio of the system itself. Equilibrium Composition: The chemical software package HSC Chemistry Version 5.1 was utilized here to determine equilibrium abundances of gaseous and solid compounds. Each calculation was done over the temperature range 3K to 6000K with a total pressure of 10-6 bars. This method has been utilized successfully in other studies (e.g. [7]). Abundance Results: Example abundance distribution plots can be seen in Figures 1 - 3. These figures focus in on the region where T< 2000K as this is where condensation first begins to occur. Using the nominal nebular model of [8], this corresponds to the region of the midplane located beyond 0.75AU from the host star at t=0. High-temperature inner regions (T>1000K, initially within 4.2AU) are dominated by gaseous H, CO and N2, with minor amounts of solid iron, enstatite and forsterite also present. The cooler (outer) regions of the disk are dominated by gaseous H2, H2O, CH4 and NH3, with solid water, enstatite, forsterite and iron. This broad trend closely mirrors the compositional trends of our own solar system. As a simplistic approximation of the mass distribution within HD6434, the amount of solid graphite present within concentric rings, each of width 0.1AU and height 0.1 AU, was determined for radii from 0.1 to 11.2 AU. Pressure and temperature values for each ring were obtained from the nominal model of [8]. We thus find that the entire system contains initially approximately 2.26x1025 kg (3.8 MEarth) of solid graphite. This mass by itself is not enough to produce HD6434b (M = 0.48MJ, 9.12x1026 kg), but if we assume the graphite remains at its average density of 2.16 g/cm3 (i.e. neglect phase changes), then this mass would result in a protoplanet with a radius of 13,347 km. A planet of this size and mass is capable of retaining a H2 and CO atmosphere beyond approx. 9.6AU, possibly accounting for the “missing” mass. Obviously, this approach is simplistic but it does illustrate the need to determine the mass distribution more accurately and for a wider selection of stars as it has the potential to impact heavily on planetary formation theory. Log (kmol) -3.0 Log(kmol) -3.0 H(g) H(g) H2O(g) H2O H2O H2O(g) -3.5 -3.5 CO(g) O(g) NH3(g) CH4(g) Ne(g) -4.0 -4.0 Mg(g) N2(g) S iO(g) CO(g) O(g) Fe(g) NH3(g) S iO(g) N2(g) MgS iO3 FeS Mg2S iO4 Mg(g) H2S (g) Fe 2000 -4.5 Fe(g) S (g) -5.0 0 500 1000 Temperature K 1500 -4.5 MgS iO3 CH4(g) Fe Mg2S iO4 Fe3O4 *2FeO*S iO2 -5.0 0 500 1000 Temperature K 1500 2000 Figure 3: HD30177 ([Fe/H] = 0.20) abundance distribution Figure 1: Solar abundance distribution Log(kmol) -2.5 Log (kmol) -2.5 CH4(g) H(g) H(g) C H2O H2O(g) -3.0 -3.0 O(g) CO(g) -3.5 H2O -3.5 NH3(g) CH4(g) CO(g) -4.0 N2(g) Ne(g) Mg(g) S iO(g) Fe(g) H2O(g) C2H2(g) -4.0 CS (g) -4.5 Fe MgS iO3 Fe3O4 -4.5 MgS Mg(g) MgS iO3 C(g) S i(g) Mg2S iO4 -5.0 0 500 1000 Temperature K 1500 2000 Figure 2: HD145675 ([Fe/H] = 0.43) abundance distribution -5.0 0 500 1000 Temperature K H2S (g) NH3(g) S iS (g) 1500 2000 Figure 4: HD6434 ([Fe/H] = -0.52) abundance distribution References: [1] Berião, P. et al. (2005) A&A, 438, 251. [2] Ecuvillon, A. et al. (2004) A&A, 418, 703. [3] Ecuvillon, A. et al. (2004) A&A, 426, 619. [4] Bodaghee, A. et al. (2003) A&A, 404, 715. [5] Ecuvillon, A. et al. (2006) A&A, 445, 633. [6] Asplund, M., Grevesse, N. & Sauval, A. J. (2004) astro-ph/0410214. [7] Pasek, M. et al. (2005) Icarus, 175, 1. [8] Hersant, F., Gautier, D. and Huré, J. (2001) ApJ, 554, 391. Background image of Orion nebula obtained from http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/newsdesk/archive/releases/1995/45/