Sherman's March to the Sea, 1864

advertisement

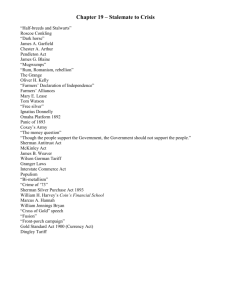

Sherman’s March to the Sea General Sherman's march through the state of Georgia from Atlanta to Savannah was one of the most devastating blows to the South in the American Civil War. Not only did he take control of Atlanta, a major railroad hub, and Savannah, a major sea port, but he laid the land between Atlanta and Savannah to waste, destroying all that was in his path. Before the March Prior to his famous march to the sea, General Sherman led 100,000 men into the southern city of Atlanta. He defeated Confederate General John Hood at the Battle of Atlanta on July 22, 1864. He had a lot more soldiers than General Hood who only had 51,000. General Sherman finally gained control of the city of Atlanta on September 2, 1864. The March to Savannah After establishing control of Atlanta, General Sherman decided to march to Savannah, Georgia and take control of the sea port there. He was well into enemy territory, however, and didn't have supply lines back to the north. This was considered a risky march. What he decided to do was live off the land. He would take from the farmers and livestock along the way to feed his army. Map of Sherman's March to Savannah - click for larger view General Sherman also decided that he could hurt the Confederacy even further by destroying cotton gins, lumber mills, and other industries that helped the Confederate economy. His army burned, looted, and destroyed much that was in their path during the march. This was a deep blow to the resolve of the Southern people. During the march, Sherman divided up his army in four different forces. This helped to spread out the destruction and give his troops more area to get food and supplies. It also helped to confuse the Confederate Army so they weren't sure exactly what city he was marching to. Taking Savannah When Sherman arrived in Savannah, the small Confederate force that was there fled and the mayor of Savannah surrendered with little fight. Sherman would write a letter to President Lincoln telling him he had captured Savannah as a Christmas gift to the president. Interesting Facts about Sherman's March to the Sea The tactic of destroying much in an army's path is called "scorched earth". The Union soldiers would heat up rail road ties and then bend them around tree trunks. They were nicknamed "Sherman's neckties". Sherman's decisive victories are thought to have assured Abraham Lincoln's reelection as president. The soldiers who went out to forage for food for the army were called "bummers". Sherman estimated that his army did $100m in damage and that's in 1864 dollars! From November 15 until December 21, 1864, Union General William T. Sherman led some 60,000 soldiers on a 285-mile march from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia. The purpose of this “March to the Sea” was to frighten Georgia’s civilian population into abandoning the Confederate cause. Sherman’s soldiers did not destroy any of the towns in their path, but they stole food and livestock and burned the houses and barns of people who tried to fight back. The Yankees were “not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people,” Sherman explained; as a result, they needed to “make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war.” The Fall of Atlanta General Sherman’s troops captured Atlanta on September 2, 1864. This was an important triumph, because Atlanta was a railroad hub and the industrial center of the Confederacy: It had munitions factories, foundries and warehouses that kept the Confederate army supplied with food, weapons and other goods. It stood between the Union Army and two of its most prized targets: the Gulf of Mexico to the west and Charleston to the East. It was also a symbol of Confederate pride and strength, and its fall made even the most loyal Southerners doubt that they could win the war. (“Since Atlanta,” South Carolinian Mary Boykin Chestnut wrote in her diary, “I have felt as if…we are going to be wiped off the earth.”) Did You Know? In theyears afterthe Civil War, fighting forces around the world have made use of Sherman’s “total war” strategy. March to the Sea After they lost Atlanta, the Confederate army headed west into Tennessee and Alabama, attacking Union supply lines as they went. Sherman was reluctant to set off on a wild goose chase across the South, however, and so he split his troops into two groups. Major General George Thomas took some 60,000 men to meet the Confederates in Nashville, while Sherman took the remaining 62,000 on an offensive march through Georgia to Savannah, “smashing things” (he wrote) “ to the sea.” “Make Georgia Howl” Sherman believed that the Confederacy derived its strength not from its fighting forces but from the material and moral support of sympathetic Southern whites. Factories, farms and railroads provided Confederate troops with the things they needed, he reasoned; and if he could destroy those things, the Confederate war effort would collapse. Meanwhile, his troops could undermine Southern morale by making life so unpleasant for Georgia’s civilians that they would demand an end to the war. To that end, Sherman’s troops marched south toward Savannah in two wings, about 30 miles apart. On November 22, 3,500 Confederate cavalry started a skirmish with the Union soldiers at Griswoldville, but that ended so badly–650 Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded, compared to 62 Yankee casualties–that Southern troops initiated no more battles. Instead, they fled South ahead of Sherman’s troops, wreaking their own havoc as they went: They wrecked bridges, chopped down trees and burned barns filled with provisions before the Union army could reach them. The Union soldiers were just as unsparing. They raided farms and plantations, stealing and slaughtering cows, chickens, turkeys, sheep and hogs and taking as much other food–especially bread and potatoes–as they could carry. (These groups of foraging soldiers were nicknamed “bummers,” and they burned whatever they could not carry.) The marauding Yankees needed the supplies, but they also wanted to teach Georgians a lesson: “it isn’t so sweet to secede,” one soldier wrote in a letter home, “as [they] thought it would be.” Sherman’s troops arrived in Savannah on December 21, 1864, about three weeks after they left Atlanta. The city was undefended when they got there. (The 10,000 Confederates who were supposed to be guarding it had already fled.) Sherman presented the city of Savannah and its 25,000 bales of cotton to President Lincoln as a Christmas gift.Early in 1865, Sherman and his men left Savannah and pillaged and burned their way through South Carolina to Charleston. In April, the Confederacy surrendered and the war was over. Total War Sherman’s “total war” in Georgia was brutal and destructive, but it did just what it was supposed to do: it hurt Southern morale, made it impossible for the Confederates to fight at full capacity and likely hastened the end of the war. “This Union and its Government must be sustained, at any and every cost,” explained one of Sherman’s subordinates. “To sustain it, we must war upon and destroy the organized rebel forces,–must cut off their supplies, destroy their communications…and produce among the people of Georgia a thorough conviction of the personal misery which attends war, and the utter helplessness and inability of their ‘rulers’ to protect them…If that terror and grief and even want shall help to paralyze their husbands and fathers who are fighting us…it is mercy in the end.” Sherman's March to the Sea Anne J. Bailey, Georgia College and State University, 09/05/2002 Last edited by NGE Staff on 12/01/2014 William T. Sherman General Sherman’s march to the Sea, the most destructive campaign against a civilian population during the Civil War (1861-65), began in Atlanta on November 15, 1864, and concluded in Savannah on December 21, 1864. Union general William T. Sherman abandoned his supply line and marched across Georgia to the Atlantic Ocean to prove to the Confederate population that its government could not protect the people from invaders. He practiced psychological warfare; he believed that by marching an army across the state he would demonstrate to the world that the Union had a power the Confederacy could not resist. "This may not be war," he said, "but rather statesmanship." Preparation After Sherman's forces captured Atlanta on September 2, 1864, Sherman spent several weeks making preparations for a change of base to the coast. He rejected the Union plan to move through Sherman's Commanders Alabama to Mobile, pointing out that after Rear Admiral David G. Farragut closed Mobile Bay in August 1864, the Alabama port no longer held any military significance. Rather, he decided to proceed southeast toward Savannah or Charleston. He carefully studied census records to determine which route could provide food for his men and forage for his animals. Although U.S. president Abraham Lincoln was skeptical and did not want Sherman to move into enemy territory before the presidential election in November, Sherman persuaded his friend Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant that the campaign was possible in winter. Through Grant's intervention Sherman finally gained permission, although he had to delay until after election day. Confederate Response After General John Bell Hood abandoned Atlanta, he moved the Confederate Army of Tennessee outside the city to recuperate from the previous campaign. In early October he began a raid toward Chattanooga, Tennessee, in an effort to draw Sherman back over ground the two sides had fought for since May. But instead of tempting Sherman to battle, Hood turned his army west and marched into Alabama, abandoning Georgia to Union forces. Apparently, Hood hoped that if he invaded Tennessee, Sherman would be forced to follow. Sherman, however, had anticipated this strategy and had sent Major General George H. Thomas to Nashville to deal with Hood. With Georgia cleared of the Confederate army, Sherman, facing only scattered cavalry, was free to move south The March Sherman divided his approximately 60,000 troops into two roughly equal wings. The right wing was under Oliver O. Howard. Peter J. Osterhaus commanded the Fifteenth Corps, and Francis P. Blair Jr. commanded the Seventeenth Corps. The left wing was commanded by Henry W. Slocum, with the Fourteenth Corps under Jefferson C. Davis and the Twentieth Corps under Alpheus S. Williams. Judson Kilpatrick led the cavalry. Sherman had about 2,500 supply wagons and 600 ambulances. Before the army left Atlanta, the general issued an order outlining the rules of the march, but soldiers often ignored the restrictions on foraging. The two wings advanced by separate routes, generally staying twenty miles to forty miles apart. The right wing headed for Macon, the left wing in the direction of Augusta, "Bummers" before the two commands turned and bypassed both cities. They now headed for the state capital at Milledgeville. Opposing Sherman's advance was Confederate cavalry, about 8,000 strong, under Major General Joseph Wheeler and various units of Georgia militia under Gustavus W. Smith. Although William J. Hardee had overall command in Georgia, with his headquarters at Savannah, neither he nor Governor Joseph E. Brown could do anything to stop Sherman's advance. Sherman's foragers quickly became known as "bummers" as they raided farms and plantations. On November 23 the state capital peacefully surrendered, and Sherman occupied the vacant governor's mansion and capitol building. Military Encounters There were a number of skirmishes between Wheeler's cavalry and Union troopers, but only two battles of any significance. The first came east of Macon at the factory town of Griswoldville on November 22, when Georgia militia faced Union infantry with disastrous results. The Confederates suffered 650 men killed or wounded in a one-sided battle that left about Fort McAllister 62 casualties on the Union side. The second battle occurred on the Ogeechee River twelve miles below Savannah. Union infantry under William B. Hazen assaulted and captured Fort McAllister on December 13, thus opening the back door to the port city. The most controversial event involved contrabands (escaped slaves) who followed the liberating armies. At Ebenezer Creek on December 9, Jefferson C. Davis removed the pontoon bridge before the slaves crossed. Frightened men, women, and children plunged into the deep water, and many drowned in an attempt to reach safety. After the march Davis was soundly criticized by the Northern press, but Sherman backed his commander by pointing out that Davis had done what was militarily necessary. Sherman at Savannah After Fort McAllister fell, Sherman made preparations for a siege of Savannah. Sherman's Headquarters in Savannah Confederate lieutenant general Hardee, realizing his small army could not hold out long and not wanting the city leveled by artillery as had happened at Atlanta, ordered his men to abandon the trenches and retreat to South Carolina. Sherman, who was not with the Union army when Mayor Richard Arnold surrendered Savannah (he had gone to Hilton Head, South Carolina, to make preparations for a siege and was on his way back to Georgia), telegraphed President Lincoln on December 22 that the city had fallen. He offered Savannah and its 25,000 bales of cotton to the president as a Christmas present. Consequences of the March Sherman's march frightened and appalled Southerners. It hurt morale, for civilians had believed the Confederacy could protect the home front. Sherman's March to the Sea Sherman had terrorized the countryside; his men had destroyed all sources of food and forage and had left behind a hungry and demoralized people. Although he did not level any towns, he did destroy buildings in places where there was resistance. His men had shown little sympathy for Millen, the site of Camp Lawton, where Union prisoners of war were held. Physical attacks on white civilians were few, although it is not known how slave women fared at the hands of the invaders. Often male slaves posted guards outside the cabins of their women. Confederate president Jefferson Davis had urged Georgians to undertake a scorched-earth policy of poisoning wells and burning fields, but civilians in the army's path had not done so. Sherman, however, burned or captured all the food stores that Georgians had saved for the winter months. As a result of the hardships on women and children, desertions increased in Robert E. Lee's army in Virginia. Sherman believed his campaign against civilians would shorten the war by breaking the Confederate will to fight, and he eventually received permission to carry this psychological warfare into South Carolina in early 1865. By marching through Georgia and South Carolina he became an archvillain in the South and a hero in the North. Sherman's March to the Sea, 1864 A Southerner's Perspective Atlanta fell to Sherman's Army in early September 1864. He devoted the next few weeks to chasing Confederate troops through northern Georgia in a vain attempt to lure them into a decisive fight. The Confederate's evasive tactics doomed Sherman's plan to achieve victory on the battlefield so he developed an alternative strategy: destroy the South by laying waste to its economic and transportation infrastructure. Sherman's "scorched earth" campaign began on November 15th when he cut the last telegraph wire that linked him to his superiors in the North. He left Atlanta in flames and pointed his army south. No word would be heard from him for the next five weeks. Unbeknownst to his enemy, Sherman's objective was the port of Savannah. His army of 65,000 cut a broad swath as it lumbered towards its destination. Plantations were burned, crops destroyed and stores of food pillaged. In the wake of his progress to the sea he left numerous "Sherman sentinels" (the "Sherman's Sentinels" chimneys of burnt out houses) and "Sherman neckties" Only the chimneys stand after (railroad rails that had been heated and wrapped around trees.). a visit by Sherman's Army Along the way, his army was joined by thousands of former slaves who brought up the rear of the march because they had no other place to go. Sherman's army reached Savannah on December 22. Two days later, Sherman telegraphed President Lincoln with the message "I beg to present to you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah..." It was the beginning of the end for the Confederacy. Sherman stayed in Savannah until the end of January and then continued his scorched earth campaign through the Carolinas. On April 26, Confederate troops under General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to Sherman in North Carolina; seventeen days after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. "Oh God, the time of trial has come!" Dolly Sumner Lunt was born in Maine in 1817. She moved to Georgia as a young woman to join her married sister. She became a school teacher in Covington, Ga. where she met and married Thomas Burge, a plantation owner. When her husband died in 1858, Dolly was left alone to manage the plantation and its slaves. Dolly kept a diary of her experiences and we join her story as Sherman's army approaches her home: November 19, 1864 Slept in my clothes last night, as I heard that the Yankees went to neighbor Montgomery's on Thursday night at one o'clock, searched his house, drank his wine, and took his money and valuables. As we were not disturbed, I walked after breakfast, with Sadai [the narrator's 9-yearold daughter], up to Mr. Joe Perry's, my nearest neighbor, where the Yankees were yesterday. Saw Mrs. Laura [Perry] in the road surrounded by her children, seeming to be looking for some one. She said she was looking for her husband, that old Mrs. Perry had just sent her word that the Yankees went to James Perry's the night before, plundered his house, and drove off all his stock, and that she must drive hers into the old fields. Before we were done talking, up came Joe and Jim Perry from their hiding-place. Jim was very much excited. Happening to turn and look behind, as we stood there, I saw some blue-coats coming down the hill. Jim immediately raised his gun, swearing he would kill them anyhow. 'No, don't!' said I, and ran home as fast as I could, with Sadai. I could hear them cry, 'Halt! Halt!' and their guns went off in quick succession. Oh God, the time of trial has come! A man passed on his way to Covington. I halloed to him, asking him if he did not know the Yankees were coming. 'No - are they?' 'Yes,' said I; 'they are not three hundred yards from here.' 'Sure enough,' said he. 'Well, I'll not go. I don't want them to get my horse.' And although within hearing of their guns, he would stop and look for them. Blissful ignorance! Not knowing, not hearing, he has not suffered the suspense, the fear, that I have for the past forty-eight hours. I walked to the gate. There they came filing up. I hastened back to my frightened servants and told them that they had better hide, and then went back to the gate to claim protection and a guard. But like demons they rush in! My yards are full. To my smoke-house, my dairy, pantry, kitchen, and cellar, like famished wolves they come, breaking locks and whatever is in their way. The thousand pounds of meat in my smoke-house is gone in a twinkling, my flour, my meat, my lard, butter, eggs, pickles of various kinds - both in vinegar and brine - wine, jars, and jugs are all gone. My eighteen fat turkeys, my hens, chickens, and fowls, my young pigs, are shot down in my yard and hunted as if they were rebels themselves. Utterly powerless I ran out and appealed to the guard. 'I cannot help you, Madam; it is orders.' ...Alas! little did I think while trying to save my house from plunder and fire that they were forcing my boys [slaves] from home at the point of the bayonet. One, Newton, jumped into bed in his cabin, and declared himself sick. Another crawled under the floor, - a lame boy he was, but they pulled him out, placed him on a horse, and drove him off. Mid, poor Mid! The last I saw of him, a man had him going around the garden, looking, as I thought, for my sheep, as he was my shepherd. Jack came crying to me, the big tears coursing down his cheeks, saying they were making him go. I said: 'Stay in my room.' But a man followed in, cursing him and threatening to shoot him if he did not go; so poor Jack had to yield. ...Sherman himself and a greater portion of his army passed my house that day. All day, as the sad moments rolled on, were they passing not only in front of my house, but from behind; they tore down my garden palings, made a road through my back-yard and lot field, driving their stock and riding through, tearing down my fences and desolating my home - wantonly doing it when there was no necessity for it. ...As night drew its sable curtains around us, the heavens from every point were lit up with flames from burning buildings. Dinnerless and supperless as we were, it was nothing in comparison with the fear of being driven out homeless to the dreary woods. Nothing to eat! I could give my guard no supper, so he left us. A family flees the approach of Sherman's Army My Heavenly Father alone saved me from the destructive fire. My carriage-house had in it eight bales of cotton, with my carriage, buggy, and harness. On top of the cotton were some carded cotton rolls, a hundred pounds or more. These were thrown out of the blanket in which they were, and a large twist of the rolls taken and set on fire, and thrown into the boat of my carriage, which was close up to the cotton bales. Thanks to my God, the cotton only burned over, and then went out. Shall I ever forget the deliverance? November 20, 1864. About ten o'clock they had all passed save one, who came in and wanted coffee made, which was done, and he, too, went on. A few minutes elapsed, and two couriers riding rapidly passed back. Then, presently, more soldiers came by, and this ended the passing of Sherman's army by my place, leaving me poorer by thirty thousand dollars than I was yesterday morning. And a much stronger Rebel!" Week 30 In mid-November, Sherman writes Ulysses S. Grant of his strategy for the Savannah Campaign…the March to the Sea. His plan is unheard of: abandon supply lines and nonessentials and survive off the land. Above all, Sherman vows to show inhabitants of the South that war and personal ruin are synonymous. He’ll see to it that his “scorched earth” policy has both economic and psychological impact. Week 31 It is mid-November, 1864. Before leaving Atlanta on the March to the Sea, the Union army destroys railroads, factories, anything in Atlanta’s business district that may be of service to the Confederacy. Soldiers ignore Sherman’s order that churches and houses be spared; officers make no attempt to stop them. Forty percent of Atlanta is destroyed as the Union army marches out beneath clouds of smoke. Week 32 In late November, the Yankee army moves through Georgia, ransacking property for supplies. Near Sandersville, 19-year-old Imogene Hoyle’s family hides jewelry, money, and clothes outside their home. Foraging parties seize food and livestock on the move; Sherman knows the army will famish if they linger in one place. With them, go thousands of slaves. Locals “fear the negroes” more than anything else. Week 33 It is the third week of Sherman’s March. General Beauregard and Confederate authorities urge the public to delay his advance. But for 36 days, the Union army marches onward with little resistance. The State Capitol in Milledgeville surrenders, and Sherman occupies the Governor’s mansion. Lincoln awaits news in Washington. Confederates don’t know where he is going. Sherman is on the loose in Georgia. Week 34 With the March to the Sea four weeks underway, thousands of refugee slaves in search of liberation follow the Union army. They are both boon and bane to Sherman’s cause: providing labor, but hindering movement. At Ebenezer Creek, the bridge is dismantled so none can follow. Countless refugees drown; survivors are shot by Confederate troops or remanded to their owners. The enslaved are not yet free. Week 35 It is mid-December, 1864. Union forces capture Fort McAllister, opening the Ogeechee River to its supply ships off the Georgia coast. Led by General Hardee, 15,000 Confederates guard Savannah. On the 17th, Sherman telegrams him, demanding to surrender. Hardee does not yield, though Savannah Mayor, Richard Arnold, does. Sherman wires President Lincoln, presenting Savannah as a Christmas gift. Week 36 It is the final week of 1864. Atlanta, the South’s industrial hub, is decimated, the damage totaling nearly $100 million in 1864 dollars. In forcing on the Confederacy “the hard hand of war,” Sherman proves the South cannot be protected; public confidence in the Confederate government collapses. Sherman’s final blow is to lead his army through South Carolina and beyond, the heartland of secession. Week 37 As Sherman’s war in Georgia concludes, the Confederate cause is defeated. Sherman has destroyed property, left thousands destitute, and is the most despised man in the South. But his methods prove true: he has crippled the Confederacy and shortened the war. Lincoln’s reelection and emancipation are won in tandem. The promise of freedom does not guarantee social justice. But there is hope in 1865.