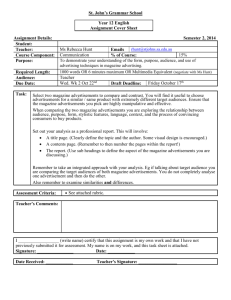

MY advertisement analysis

advertisement

Riley Stauffer Ad Analysis CMST 328 Dr. Pearson Do the Shoes Make the Woman? The use of sexualized images of women in advertisements to sell products and services to men has long been reported on and studied, but less attention has been given to how and why advertisers use these very same images to appeal to women. Advertisements for contemporary women’s footwear designers Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman, the first appearing in the March 2013 issue of InStyle Magazine and the latter appearing in the April 2013 issue of Elle Magazine, are two such examples. Sam Edelman’s 2013 digital and print advertising campaign was shot entirely in black and white and features supermodel Kate Upton lounging in a variety of positions, dressed in black and white lingerie, in what appears to be a retro-styled bedroom. Stuart Weitzman’s Spring 2013 advertisement campaign, also shot in black and white, features supermodel Kate Moss in various states of undress, most often in underpants and an unbuttoned white or black sweater, blazer, or men’s dress shirt, posing in an empty white room. By applying Charland’s theory of constitutive rhetoric, I will argue that these Stuart Weitzman and Sam Edelman advertisements constitute their audience, or readers of female fashion magazines, as “sex objects” and thereby perpetuate an ideology typical of patriarchal societies in which women are viewed as passive sex objects that occupy a position of subordination to their male counterparts. I will first begin with a detailed description of both ads, followed by an explanation of Maurice Charland’s theory of constitutive rhetoric, including what he identifies as the two ideological effects of constitutive rhetoric in advertisements - the constitution of audiences into a collective identity and an illusion of freedom – both of which ultimately support the culture’s dominant ideology. After fully explaining Charland’s theory, I will apply it to Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman’s advertisements to show how both ads constitute their female audiences as “sex objects” and create an illusion of freedom that links buying the advertised products with looking and being like the women featured in the advertisements. Finally, I will show how this cultivated collective identity and illusion of freedom contribute to the patriarchal ideology that views women as dependent, submissive, and powerless ornamental objects. One of the first advertisements of Sam Edelman’s 2013 campaign appeared in the March 2013 issue of InStyle Magazine. In this advertisement, supermodel Kate Upton lies on a chaise lounge chair with light polka-dot upholstery and a decorative white frame and legs. This retro style chaise lounge is not positioned directly in the center of the shot, but, rather, is closer to the left edge of the shot, and the bottom of the chair appears to be angled toward the camera, perhaps because the shoes being advertised are positioned in the bottom left corner of the frame. On the chair, Kate Upton faces away from the audience and is dressed in a short, skin-tight black slip with panels of sheer mesh on the side and a small keyhole at the center of her back. She also wears strappy, open-toe black heels with what appear to be silver studs or grommets on each strap. Upton, in a reclining position, positions her head tilted upwards, resting on the top of the chaise lounge, which exposes her neck, and folds her arms so one hand is resting underneath her cheek and the other is touching her forearm. Upton’s legs are bent at her knees and her feet haphazardly dangle off the side of the chaise closest to the audience. Because Upton is facing away from the audience, her image is only visible through tall mirrors that apparently hang on the back of three white wooden doors. Her cleavage is visible in her reflection. In the upper left hand corner of the shot, there appears to be the edge of a lampshade and the leg of a table visible. Aligned with the bottom right corner of the advertisement, “Sam Edelman” is scrawled in large, white cursive text. The second advertisement I have selected appeared in the April 2013 issue of Elle Magazine as part of Stuart Weitzman’s Spring 2013 advertisement campaign. In this black and white advertisement, supermodel Kate Moss sits in a white room on a hard, white box with “Stuart Weitzman” embossed on the bottom right side of the box in tall, thin capital letters. Although looking at the camera, Kate Moss is seated so she is angled away from the audience. Wearing what appears to be an unbuttoned silky black dress shirt and a white string bikini, Moss holds her hands behind her head, exposing an extremely thin, almost pre-pubescent midsection. Moss, with her legs crossed, keeps the bottom of her top leg from touching the top of her bottom, so while one foot is on the ground, the other sits above it, next to her shin. The shoes Moss wears, on the bottom of the image to the left of the brand’s name, are white, cross strap, peep-toe heels with what seems to be dark, round embellishments lining the straps. Before I can analyze the advertisements I have just described using Charland’s theory of constitutive rhetoric, I must explain the basis and important aspects of the theory. Maurice Charland developed his theory of constitutive rhetoric to describe ideological processes, based on theories by Kenneth Burke and Louis Althusser, in 1987. First and foremost, an ideology is a set of beliefs and values that a given culture perceives as “normal” and takes for granted as common sense, but which actually serves the interests of the ruling class in that society. Dr. Sarah R. Stein, an Associate Professor of Communication Media at North Carolina State University and a documentary film editor, explains in “The ‘1984 Macintosh Ad: Cinematic Icons and Constitutive Rhetoric in the Launch of a New Machine” (2002) that ideologies, or dominant beliefs of a culture, are perpetuated through advertisements. Charland identifies two ideological effects of the constitutive rhetoric of advertisements that aid in imparting dominant ideologies to audiences: first, the “constituting [of] a collective subject through narratives that foster an identification superseding divisive individual or class interests” and second, “the illusion of freedom and agency of the narrative’s protagonist” (Stein, 2002, p. 174). Constitutive rhetoric’s first ideological effect is constituting audiences, or bringing audiences into being. The constitutive rhetoric of advertisements tells a story that builds identification and positions the audiences to adopt a certain identity or lifestyle, therefore creating a collective identity. These ad narratives construct viewers as acquisitive agents motivated by lack. In Stein’s words (2002), “Advertising discourse constitutes viewers as deficient in some quality, attribute or value…a deficiency constructed as happily remedied through the consumption of material objects” (p. 174). Constitutive rhetoric also produces a second ideological effect, an illusion of freedom, meaning that the narrative the advertisement offers, gives the audience certain forms of agency, or the freedom to speak, act, and/or function however they choose. However, when subjects buy into the narrative the ad sells to them, they are not really invited to speak, act, and/or be in any truly alternative way. The agency of the audience is limited by the ideology, or the outcome of the narrative, because the available choices have already been chosen for the audience. In other words, Charland emphasizes that audience interpolated into a collective identity by the constitutive rhetoric of the narrative of any given ad is not actually encouraged to act freely, but is just encouraged to buy the product advertised. Advertisements hail their audience into an identity slot that conforms to, and thus preserves, the culture’s dominant ideology (Stein, 2002, p. 189). Now, one can begin to understand how the Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman’s ads construct the readers of InStyle and Elle as a collective audience of “sex objects” who are motivated to buy the brands’ shoes because of a perceived lacking. In “Varieties of Feminist Criticism” (2011), Dr. Barry Brummett, professor and author, articulates that advertisements “make women into objects” with relatively little agency, which functions as “the assertion of a kind of lack, for objects lack the power of action and initiation” (p. 182). In advertisements, women and men are given different forms of agency. Men are constructed as active subjects, while women are constructed as sedentary objects. In Codes of Gender: Identity and Performance in Pop Culture, founder and Executive Director of the Media Education Foundation Sut Jhally, cites sociologist Erving Goffman’s assertion that frequently women in advertisements are shown in “canting postures” to emphasize their lack of agency and power (2009). “Canting postures” put women in a defenseless posture and convey an acceptance of subordination. In Sam Edelman’s ad, Upton takes on many different canting postures: she is shown lying down or reclining, with her knees bent, and is engaging in “self-touching” by touching her cheek with one hand and her forearm with the other, all of which “convey a sense of the body as being a delicate and precious thing” and leave her vulnerable, unbalanced, and defenseless against possible threats. Finally, Upton also engages in the “most extreme form” of “canting” because her head is tilted up and her neck is exposed, similar to how dogs look up to people more powerful than them (Jhally, 2009). Similarly, in the Stuart Weitzman ad, Moss is photographed sitting down and tilted away from the camera in a position that “takes the body away from being upright and perpendicular” and “communicates submission and powerlessness” (Jhally, 2009). Moreover, Moss sits in a crossed leg position, which “is a submissive and powerless position, utterly dependent on the world being risk and danger free” (Jhally, 2009). Clearly, in both advertisements, the position of the models portray women as powerless, subordinate creatures lacking agency, thus making them equivalent to objects. Because objects are typically instruments that have a function, the contortion of the female body into positions conveying passivity and vulnerability is only one element of the canting posture. Women are also depicted as “sexually available” by positioning themselves in a way that offers themselves for use as a sexual instrument. Both Upton and Moss are dressed in revealing clothing, which puts their bodies on display. By lifting up her hands to give the viewer an unobstructed view of her near-nakedness, Moss seems to be a willing participant in her sexual objectification. Moreover, Upton’s position facing towards the mirror creates the assumption that she is primarily concerned with her physical appearance and emphasizes both her own and the audience’s focus on her body and physical attractiveness. In “Critical Approaches to Rhetoric” (2011), Dr. Timothy A. Borchers states that because “rhetoric can create standards against which people are measured”, advertisements affect what people purchase (p. 111). In ads, “the meaning of one thing is made equivalent to another, the visual signifier is substituted for the product’s signified” (Stein, 2009, p. 174). In other words, we buy not just the product, but the images that the advertisements sell us. Advertisements in fashion magazines that depict women as sex objects, such as the two I have chosen, make viewers feel inadequate, or lacking, when they compare themselves to the images, which encourages them to buy the product being advertised. This manipulation of audience leads to the second ideological effect of constitutive rhetoric: an illusion of freedom. Women believe that they are practicing freedom and agency when buying shoes from Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman because they are choosing to make themselves as sexy and desirable as the supermodels in the advertisements. However, by striving to look like the sexualized depictions of women in the ads, the audience is conforming to ideological patriarchal norms that position women as subordinate, powerless creatures. The agency of the audience is still limited by the patriarchal society in which they live. Through both the illusion of freedom given and the collective identity that constitutes the audience as “sex objects” inherently lacking agency and power, the Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman advertisements support an ideology typical of patriarchal societies that treats women as passive sex objects and equates femininity with submission, subordination, and a lower rank on the hierarchy of power. Ideologies are “generated by the system of artifacts that comprise a culture” (Borchers, 2011, p. 194). Media and advertising happens to be one of the most important artifacts. Within American culture, there already exists a hierarchy that positions masculinity above femininity because gender is culturally constructed, not biological. However, advertising takes this inequality and “concentrates it even more” by giving it even more “priority and emphasis – while at the same time ignoring other things” which creates more powerful meanings of and ideas about gender (Jhally, 2009). By depicting women in canting postures, advertisements use female bodies “to demonstrate the broader social idea that what the culture defines as feminine has a subordinate relationship to what the culture defines as masculine” (Jhally, 2009). Canting positions are so pervasive across our media landscape that the submissiveness, powerlessness, and dependency they convey seem to “define a core aspect of femininity” (Jhally, 2009). Moreover, because canting positions are sexualized, the notion that female sexuality is equated with submission and compliance is reinforced. The constitutive rhetoric of advertisements encourages viewers to adopt the hyper-sexualized feminine image they display, which forms a collective audience of “sex objects”. Because advertising plays such a large role in establishing our conscious understanding of the world around us, the gender inequality of patriarchal ideology is personified and embedded in the behaviors and thought processes of the audience. Finally, the constitutive rhetoric of the Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman ads produces an illusion of freedom that convinces female viewers that they are enacting their freedom and agency by buying Sam Edelman or Stuart Weitzman shoes. However, when consumers buy these products based on a desire to look and act like the sexually objectified women in these ads, they are actually performing stereotypical gender roles. Dr. Julia T. Wood, author of Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, & Culture (2011), explains: “The very qualities women are encouraged to develop (beauty, sexiness, passivity, and powerlessness) in order to meet cultural ideals of femininity contribute to objectifying and dehumanizing them” (p. 279). Instead of putting their freedom and agency into practice by buying the advertised products, the female audience is reinforcing the patriarchal conception of gender. Buying shoes by Sam Edelman and Stuart Weitzman after seeing their ads featuring Kate Moss and Kate Upton is not an empowering act, but an act that contributes to the ongoing subordination of women. To summarize, because advertisements “show or support performances of gender” and advise “audiences on how to ‘do’ different kinds of male or female roles”, advertisements work to create and perpetuate the gender inequality between men and women in the United States (Brummett, 2011, p. 180). Advertising is one of the many artifacts in American culture that serves to maintain and conserve the dominant patriarchal ideology. Additionally, due to technological advancement, we now live in a world where media and advertisements are almost impossible to escape. As a result, the images advertising bombards us with have developed a seeming normality in our everyday lives. Readers of female fashion magazines such as InStyle and Elle do not even think twice when they come across like the Stuart Weitzman and Sam Edelman ones I have analyzed. This audience is unconsciously interpolated into a collective identity of “sex objects” that motivates them to make purchases that perpetuate an ideology typical of patriarchal societies in which women are viewed as passive, sexualized objects that occupy a position of subordination to men. The pervasiveness of advertising in our lives today makes the congenital inequalities between genders of patriarchal ideology seem normal, natural, and even common sense.