Chapter 17

Futures

Markets and

Risk

Management

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2010 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Futures and Forwards

• Forward - an agreement calling for a future

delivery of an asset at an agreed-upon price

• Futures - similar to forward but has standardized

terms and is traded on an exchange.

• Key difference in futures

– Futures have secondary trading (liquidity)

– Marked to market

– Standardized contract terms such as delivery dates,

price units, contract size

– Clearinghouse guarantees performance

17-2

Key Terms for Futures Contracts

• The Futures price: agreed-upon price paid at maturity

• Long position: Agrees to purchase the underlying asset

at the stated futures price at contract maturity

• Short position: Agrees to deliver the underlying asset at

the stated futures price at contract maturity

• Profits on long and short positions at maturity

– Long = Futures price at maturity minus original futures price

– Short = Original futures price minus futures price at maturity

– At contract maturity T: FT= ST F = Futures price, S = spot price

17-3

Figure 17.2 Profits to Buyers and Sellers

of Futures and Options Contracts

Why does the payoff for the call option differ from the long futures position?

17-4

Types of Contracts

• Agricultural commodities

• Metals and minerals (including energy

contracts)

• Financial futures

– Interest rate futures

– Stock index futures

– Foreign currencies

17-5

Table 17.1 Sample of Futures Contracts

17-6

17.2 Mechanics of Trading

in Futures Markets

17-7

The Clearinghouse and Open

Interest

• Clearinghouse - acts as a party to all buyers and sellers.

– A futures participant is obligated to make or take delivery at

contract maturity

• Closing out positions

– Reversing the trade

– Take or make delivery

– Most trades are reversed and do not involve actual delivery

• Open Interest

– The number of contracts opened that have not been offset with a

reversing trade: measure of future liquidity

17-8

Figure 17.3 Trading With and Without

a Clearinghouse

The clearinghouse eliminates counterparty default risk; this

allows anonymous trading since no credit evaluation is needed.

Without this feature you would not have liquid markets.

17-9

Marking to Market and the Margin

Account

• Initial Margin: funds that must be deposited in a margin

account to provide capital to absorb losses

• Marking to Market: each day the profits or losses are

realized and reflected in the margin account.

• Maintenance or variance margin: an established value

below which a trader’s margin may not fall.

17-10

Margin Arrangements

• Margin call occurs when the maintenance

margin is reached, broker will ask for

additional margin funds or close out the

position.

17-11

Marking to Market Example

• On Monday morning you sell one T-bond futures contract at 97-27 (97

27/32% of the $100,000 face value). Futures contract price is thus

_________.

$97,843.75

• The initial margin requirement is $2,700 and the maintenance margin

requirement is $2,000.

Day

Settle

$ Value

Price Change

$97,843.75

Open

Margin

Account

Total %HPR

(cum.)

Spot HPR

(cum.)

$2700

Mon.

97-13

$97,406.25

-$437.50

$3137.50

16.2%

0.45%

Tues.

98-00

$98,000.00

$593.75

$2543.75

-5.8%

-0.16%

Wed.

100-00

$100,000.00

$2000.00

$543.75

-79.9%

-2.2%

Margin

Call

+$2156.25

$2700.00

Leverage multiplier ≈ 36

17-12

Why delivery on futures is not an issue:

$110,000

• You go long on T-Bond futures at Futures0 = ___________

$108,000

• Suppose that at contract expiration, SpotT-Bonds = ________

• With daily marking to market, you have already given seller

$108,000

________,

so if you take delivery you only owe __________

$2,000

• With no delivery made

$2,000

– the seller of the T-Bonds could sell his bonds spot for __________

$108,000 from the daily

– and the seller has ALREADY gained __________

marking to market.

$110,000

– Net proceeds to seller ___________

17-13

More on futures contracts

• Convergence of Price: As maturity approaches

the spot and futures price converge

• Delivery: Specifications of when and where

delivery takes place and what can be delivered

• Cash Settlement: Some contracts are settled in

cash rather than delivering the underlying assets

17-14

Trading Strategies

• Speculation

– Go short if you believe price will fall

– Go long if you believe price will rise

• Hedging

– Long hedge: An endowment fund will purchase stock

in 3 months. The manager buys futures now to

protect against a rise in price.

– Short hedge: A hedge fund has invested in long term

bonds and is worried that interest rates may increase.

Could sell futures to protect against a fall in price.

17-15

Figure 17.4 Hedging Revenues Using Futures,

Example 17.5 (Futures Price = $39.48)

17-16

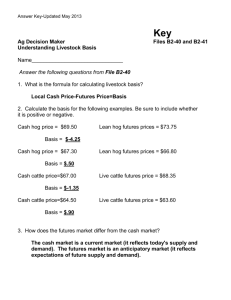

Basis and Basis Risk

• Basis - the difference between the futures

price and the spot price

– A hedger exchanges spot price risk for basis

risk.

– Basis is more stable than the spot price

– At contract maturity the basis declines to zero.

• Basis Risk - the variability in the basis that

will affect hedging performance

17-17

17.4 The Determination of

Futures Prices

17-18

Futures Pricing

• Spot-futures parity theorem

– Purchase the commodity now and store it to

T,

– Simultaneously take a short position in

futures,

– The ‘all in cost’ of purchasing the commodity

and storing it (including the cost of funds)

must equal the futures price to prevent

arbitrage.

17-19

The no arbitrage condition

Action

1. Borrow So

2. Buy spot for So

Initial Cash

Flow

S0

-S0

Cash Flow at T

-S0(1+rf)T

ST

3. Sell futures

short

0

F0 - ST

Total

0

F0 - S0(1+rf)T

Since the strategy cost 0 initially, the cash flow at T must also equal 0.

Thus:

F0 - S0(1 + rf)T = 0

F0 = S0 (1 + rf)T

The futures price differs from the spot price by the cost of carry.

Can the cost of carry be negative?

17-20

Figure 17.6 Gold Futures Prices

17-21

17.5 Financial Futures

17-22

Stock Index Futures

• Available on both domestic and

international stocks

• Several advantages over direct stock

purchase

– lower transaction costs

– easier to implement timing or allocation

strategies

17-23

Table 17.2 Stock Index Futures

17-24

Table 17.3 Correlations Among

Major US Stock Market Indexes

17-25

Creating Synthetic Stock

Positions

• Synthetic stock purchase

– Purchase of stock index futures instead of actual shares of stock

• Allows frequent trading at low cost, especially useful for foreign

investments

• Classic market timing strategy involves switching

between Treasury bills and stocks based on market

conditions.

– It is cheaper to buy Treasury bills and then shift stock market

exposure by buying and selling stock index futures.

17-26

Index Arbitrage

• Exploiting mispricing between underlying stocks

and the futures index contract

• Futures Price too high:

– Short the futures and buy the underlying stocks

• Futures price too low:

– Long the futures and short sell the underlying stocks

17-27

Index Arbitrage

• Difficult to do in practice

– Transactions costs are often too large,

– Trades must be done simultaneously

• SuperDot system assists in rapid trade execution

• ETFs available on indices

17-28

Additional Financial Futures

Contracts

• Foreign Currency

– Forward contracts

• Currency markets are the largest markets in the

world,

• Forward contracts are available from large banks,

• Used extensively by firms to hedge foreign

currency transactions.

– Futures contracts are available for major

currencies at the CME, the LIFFE and others.

• March, June, September and December delivery

contracts are available.

17-29

Figure 17.7 Spot and Forward Currency Rates

17-30

Additional Financial Futures

Contracts

• Interest Rate Futures

– Major contracts include contracts on Eurodollars,

Treasury Bills, Treasury notes and Treasury bonds.

– Contracts on some foreign interest rates are also

available.

– A short position in these contracts will benefit if

interest rates increase and may be used to hedge a

bond portfolio.

– A long position benefits if interest rates fall. A bank

that has short term loans funded by longer term debt

could hedge its funding risk with a long position.

17-31

Additional Financial Futures

Contracts

• Interest Rate Futures

– Hedging with futures will often require a cross

hedge.

• A cross hedge is hedging a spot position with a

futures contract that has a different underlying

asset.

– For example, hedge a corporate bond the firm owns by

selling Treasury bond futures.

17-32

Swaps

• Large component of derivatives market

– Interest Rate Swaps

• One party agrees to pay the counterparty a fixed

rate of interest in exchange for paying a variable

rate of interest or vice versa,

• No principal is exchanged.

17-33

Figure 17.8 Interest Rate Swap

Company A wants variable

Company B wants fixed

rate financing to match

rate financing. They will pay

their variable rate investments.

7.05%

They will pay LIBOR + 5 basis

points

Swap dealer agrees to

both deals, manages net risk

17-34

Swaps

• Currency Swaps

– Two parties agree to swap principal and

interest payments at a fixed exchange rate

• Firm may borrow money in whatever currency has

lowest interest rate and then swap payments into

the currency they prefer.

– In 2007 there were $272 trillion notional

principal in interest rate swaps outstanding

and about $12.3 trillion principal in currency

swaps. (Source, BIS)

17-35