GAPNA Chapter Meeting Content Chronic

advertisement

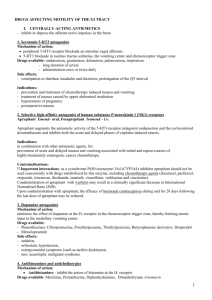

Practical Approaches Towards Improving Patient Outcomes for Chronic Constipation and Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation (IBS-C) Among Older Adults Educational Learning Objectives • Describe the elements of proper diagnosis and follow-up management of chronic constipation (CC) in older adults • Demonstrate awareness of the prevalence of irritable bowel syndromeconstipation (IBS-C) in older adults and the elements of differential diagnosis from CC • Discuss how management of CC and IBS-C varies based upon underlying etiologies and across the spectrum of older adults, from the active community dweller to the compromised long term care resident with multiple comorbidities • List common patient perceptions of constipation and describe how these may impact progress towards practitioners' clinical goals in CC and IBS-C • Identify patient education and counseling strategies that will allow advanced practice nurses (APN) to collaborate with patients and family members in the successful management of CC and IBS-C in older adults How Do We Define Constipation? • The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) definition of constipation: – Unsatisfactory defecation characterized by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both. Difficult stool passage includes straining, a sense of difficulty passing stool, incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stools, prolonged time to pass stool, or need for manual maneuvers to pass stool • The ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force also clarified what is meant by chronic: – Chronic constipation is defined as the presence of these symptoms for at least 3 months American College of Gastroenterology Chronic Constipation Task Force. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(S1):1-4. GI Symptoms Are Common in the Older Population • 35% to 40% of geriatric patients will have at least 1 GI symptom in any year – Constipation, fecal incontinence, diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, reflux disease, and swallowing disorders • Prevalence rates for constipation in the older adult population range from approximately 19% to 40% – Day Hospitals/Living at Home: 25–40% – Nursing Homes/Geriatric Hospitals: 60–80% • Irritable bowel syndrome presents in ~10% of the older population Hall KE, et al. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1305-1338. Ginsberg D, et al. Urol Nursing. 2007;27:191-200. Morley J. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23:823-832. Overlap Between Common Disorders Bloating Belching Constipation Chronic Constipation Dyspepsia IBS Discomfort GERD Heartburn Brandt L, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(S1):5-22. Abdominal Pain Regurgitation Abdominal Pain: Salient Feature Absent in Chronic Constipation (-) Abdominal Pain (+) Abdominal Pain Chronic constipation IBS with constipation Presence or absence of abdominal pain is the major differentiating feature Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(suppl 1):S5-S21. Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders 45 40 40 Population (%) 35 30 25 25-40 2-28 28 25 3-20 20 6-18 15 10 8 8 5 0 Chronic Dyspepsia Functional GERD Heartburn Constipation IBS Wong WM, Fass R. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7(4):273-278. Corazziari E. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18(4):613-631. Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):750-759. Brandt L, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(suppl11):S7-26. Hyper- Migraine Asthma Diabetes tension Wolf-Maier K, et al. JAMA. 2003;289:2363-2369. Lawrence EC. South Med J. 2004 Nov;97(11):1069-1077. CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:145-148. CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:833-837. Constipation Increases With Age and Is More Common in Women 10 25 Harari, et al Population: NHIS 1989 Criteria: self-report 20 8 6 4 2 Prevalence of Constipation (%) Prevalence of Constipation (%) 12 Study 1 N = 42,375 0 NHIS = National Health Interview Survey Higgins PDR, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750-759. Women 15 10 5 0 Age Group (years) Men Study 2 Study 3 Study 4 N = 5,430 Drossman N = 1,149 Pare N = 10,018 Stewart Sex Chronic Constipation Interferes with Daily Lives of the Aging Population Constipation No GI symptoms Mean MOS Score 100 80 60 40 20 0 Physical Role Functioning Functioning Social Functioning Mental Health Health Perception MOS = medical outcomes survey • Impact of chronic constipation on quality of life in Olmsted County, MN, residents aged ≥ 65 years • Lower score indicates worse quality of life Adapted from Talley NJ. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4(suppl 2):S3-S10. Bodily Pain Economic Impact of Constipation • 2.5 million office visits annually • 92,000 hospital admissions • 85% are given prescriptions for laxatives or cathartics • $400 million dollars spent in annually for prescription laxatives • $2253 average cost per long term care resident Economic Burden of Irritable Bowel Syndrome • IBS care: > $20 billion direct and indirect expenditures • Patients with IBS consume > 50% more health care costs than matched controls without IBS Tariq S. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:209-218. Ginsberg D, et al. Urol Nursing. 2007;27(3):191-201. ACG IBS Task Force. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:S1-S35. Normal Physiology of Defecation • • • • Increased abdominal pressure or propulsive colorectal contractions Relaxation of internal anal sphincter (autonomic) Relaxation of external anal sphincter (voluntary) Straightening of pelvic musculature (levator ani, puborectalis) At rest Lembo A, Camilleri M. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368. Muller-Lissner S. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:115-133. With straining Mediators of Gastrointestinal Function Motility Serotonin Acetylcholine Nitric oxide Substance P Vasoactive intestinal peptide Cholecystokinin Corticotropin releasing factor Visceral Sensitivity Serotonin Tachykinins Calcitonin gene-related peptide Neurokinin A Enkephalins Corticotropin releasing factor Secretion Serotonin Acetylcholine Kim DY, Camilleri M. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(10):2698-2709. Rome III Diagnostic Criteria* for Functional Constipation Chronic constipation must include 2 or more of the following: During at least 25% of defecations Straining Lumpy or hard stools Sensation of incomplete evacuation Sensation of anorectal obstruction/ blockage Manual maneuvers to facilitate defecations Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome <3 defecations per week *Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis Longstreth GF, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. Primary Causes of Chronic Constipation • Normal-transit constipation • Slow-transit constipation • Defecatory dysfunction • IBS with constipation Bosshard W, et al. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:911-930. Hadley S.K, et al. Journal of Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2501-2506. Primary Constipation • Normal-transit Constipation – Intestinal transit and stool frequency are within the normal range – Most frequent type of constipation Bosshard W, et al. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:911-930. Gallagher P, et al. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(10):807-821. Primary Constipation • Slow-transit Constipation – Characterized by prolonged intestinal transit time – Altered regulation of enteric nervous system – Decreased nitric oxide production – Impaired gastrocolic reflex – Alteration of neuropeptides (VIP, substance P) – Decreased number of interstitial cells of Cajal in the colon Lembo A, Camilleri M. N Eng J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368. Primary Constipation • Defecatory Dysfunction – More common in older women – childbirth trauma – Pelvic floor dyssynergia – Contributing factors include anal fissures, hemorrhoids, rectocele, rectal prolapse, posterior rectal herniation – Excessive perineal descent – Pathogenesis may be multifactorial – structural problem – Abnormal anorectal manometry and/or defecography [Role for biofeedback therapy] Bosshard W, et al. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:911-930. Hadley S.K, et al. Journal of Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2501-2506. Primary Constipation • Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) with Constipation – Alterations in brain-gut axis – Stress-related condition – Visceral hypersensitivity – Abnormal brain activation – Altered gastrointestinal motility – Role for neurotransmitters, hormones – Presence of non-GI symptoms Headache, back pain, fatigue, myalgia, dyspareunia, urinary symptoms, dizziness Videlock E, Chang L. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2007;36:665-685. Hadley SK, et al. Journal of Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2501-2506. Rome III Criteria for IBS-C Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort (an uncomfortable sensation not described as pain) at least 3 days per month in the last 3 months associated with 2 or more of the following: 1. Improvement with defecation 2. Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool 3. Onset associated with a change in form of stool Criteria must be fulfilled for the last 3 months, with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis In pathophysiology research and clinical trials, a pain/discomfort frequency of at least 2 days a week during screening for patient eligibility Longstreth G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. % Hard or Lumpy Stools Subtypes of IBS 100 75 50 IBS-C IBS-M 25 IBS-U 0 IBS-C: IBS with constipation IBS-U: Unsubtyped IBS IBS-M: IBS mixed IBS-D: IBS with diarrhea IBS-D 25 50 75 % Loose or Watery Stools Longstreth G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. 100 Combined Risk Factors for Constipation in the Elderly Population • • • • • • Reduced fiber intake Reduced liquid intake Reduced mobility associated with functional decline Decreased functional independence Pelvic floor dysfunction Chronic conditions – – – – Parkinson’s disease Dementia Diabetes mellitus Depression • Polypharmacy (both over the counter and prescription medications, such as NSAIDs, antacids, antihistamines, iron supplements, anticholinergics, opiates, Ca channel blockers, diuretics, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, antidepressants) Common Changes with Aging that Increase the Risk for Constipation • • • • • • • Decreased total body water Decreased colonic motility* Deterioration of nerve function Increased pelvic floor descent Decreased rectal compliance Decreased rectal sensation Age-related changes to the internal and external anal sphincter *Demonstrated in some, but not all studies Gallagher P, et al. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(10):807-821. Schiller L. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2001;30:497-515. Patient Care • Thorough patient history • Physical/abdominal/digital rectal exams • Evaluate symptoms in terms of diagnostic criteria – Chronic constipation/IBS-C • Assessment for red flags/alarm features – Need for additional testing • Treatment/Management plan Ask the Right Questions • • • • • • • • • • • Define the meaning of “constipation” How long have you experienced these symptoms? Frequency of bowel movements? Abdominal pain? Other symptoms? What is most distressing symptom? Manual maneuvers to assist with defecation? Any limitation of daily activities? Are you taking any medications? What treatment have you tried? What investigations have been done? Locke GR III, et al. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761-1778. 90 Common Patient Descriptions of Constipation 81 Percent of Patients 80 72 Physicians think: < 3 BM per week 70 60 54 50 39 40 37 36 28 30 20 10 0 Straining Hard or Incomplete lumpy emptying stools N = 1149 Pare P, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3130-3137. Stool Abdominal < 3 BM per cannot fullness or bloating week be passed Need to press on anus Stool Form Correlates With Intestinal Transit Time The Bristol Stool Form Scale Slow Transit Fast Transit Type 1 Separate hard lumps Type 2 Sausage-like but lumpy Type 3 Sausage-like but with cracks in the surface Type 4 Smooth and soft Type 5 Soft blobs with clear-cut edges Type 6 Fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool Type 7 Watery, no solid pieces O’Donnell LJD, et al. BMJ. 1990;300:439-440. Consider Secondary Causes Psychological Depression Eating disorders Drugs Surgical Abdominal/pelvic surgery Colonic/anorectal surgery Lifestyle Inadequate fiber/fluid Inactivity Constipation Metabolic/ Endocrine Hypercalcemia Hyperparathyroidism Diabetes mellitus Hypothyroidism Hypokalemia Uremia Addison’s Porphyria Opiates Antidepressants Anticholinergics Antipsychotics Antacids (Al, Ca) Ca channel blockers Iron supplements Gastrointestinal Neurological Parkinson’s Multiple sclerosis Autonomic neuropathy Aganglionosis (Hirschsprung’s, Chagas) Spinal lesions Cerebrovascular disease Candelli M, et al. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1050-1057. Locke GR, et al. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761-1766. Systemic Amyloidosis Scleroderma Polymyositis Pregnancy Colorectal: neoplasm, ischemia, volvulus, megacolon, diverticular disease Anorectal: prolapse, rectocele, stenosis, megarectum Digital Rectal Exam • Place patient in left lateral recumbent position • Visually inspect the perianal region – Fissures, hemorrhoids, masses, skin tags, or evidence of previous surgery, skin lesions • Stroke the perianal skin to elicit a reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter • Assess for paradoxical pelvic floor contraction (suggestive of pelvic floor descent) • Perform a digital assessment – Strictures, masses, a rectocele, and hemorrhoids – Examine stool for color and consistency – Check for occult blood Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:659-683. Locke GR III, et al. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761-1778. Any Alarm Symptoms? Are Diagnostic Tests Needed? • • • • • • • • Hematochezia Family history of colon cancer Family history of inflammatory bowel disease Anemia Positive fecal occult blood test “Unexplained” weight loss ≥ 10 pounds Severe, persistent constipation that is unresponsive to treatment New-onset constipation in an elderly patient Locke GR III, et al. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761-1778. Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(suppl 1):S5-S21. ACG Task Force Recommendations on Diagnostic Testing • ACG task force does not recommend diagnostic testing in patients without alarm signs or symptoms – BUT routine colon cancer screening recommended for all patients aged ≥ 50 years (African Americans aged ≥ 45 years) • Diagnostic studies are indicated in patients with alarm signs or symptoms • Thyroid function tests • Measurements of – Calcium – Electrolytes Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(suppl 1):S5-S21. Agrawal S, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:515-523. Diagnostic Tests That May Be Performed After a Referral Test Anorectal manometry Balloon expulsion Defecography Colonic transit study Colonoscopy Use Assesses the internal and external anal sphincters, pelvic floor, and associated nerves Screening test of choice for dyssynergic defecation Detects defecatory disorders Simple, office-based screening test Detects structural abnormalities of the rectum Operator dependent, poor reliability, not widely available Measures rate at which fecal mass moves through colon Provides a visual diagnosis while performing biopsies with detection and removal of polyps Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1605-1615. Lembo A, Camilleri M. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360-1368. Winawer S, et al. Gastroenterol. 2003;124:544-560. Differentiating Between Occasional and Chronic Constipation Occasional Constipation Chronic Constipation Infrequent Present for at least 3 months and may persist for years Occasional or short-term condition that may temporarily interrupt usual routine Long-term condition that may dominate personal and work life May be brought on by patient’s behavior, change in diet, lack of exercise, illness, or medication Not only related to patient’s behavior, change in diet, lack of exercise, or medication May be relieved by diet, exercise, and over-the-counter (OTC) medication May need medical attention and prescription medication Lifestyle Modifications Modification Targeted Mechanism Efficacy Increase fluid intake Increase stool volume by augmenting luminal fluid Limited; majority of fluid is absorbed before reaching the colon and is expelled via urine Increase exercise Improve motility by decreasing transit time through the GI tract Moderate; some evidence suggests this is beneficial; however, not sufficient to treat Increase dietary fiber Increase water and bulk stool volume Limited benefit compared with placebo Chung BD, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:29-32. Dukas L, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1790-1796. ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(suppl 1):S1-S4. Treating Constipation With Laxatives Laxative Bulking Agents Description Absorbs liquids in the intestines and swells to form a soft, bulky stool; the increase in fecal bulk is associated with accelerated luminal propulsion Draws water into the bowel from surrounding body tissues providing a soft stool mass and improved propulsion Osmotic Laxatives [saline, poorly absorbed mono- and disaccharides, polyethylene glycol] Stimulant Laxatives Cause rhythmic muscle contractions in the intestines, increase intestinal motility and secretions Lubricants Coats the bowel and the stool mass with a waterproof film; stool remains soft and its passage is made easier Stool Softeners Helps liquids mix into the stool and prevent dry, hard stool masses; has been said not to cause a bowel movement but instead allows the patient to have a bowel movement without straining Combinations Combinations containing more than 1 type of laxative; for example, a product may contain both a stool softener and a stimulant laxative Gallagher P, et al. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:807-821. Laxatives Laxative Type Bulk-forming Lubricating Stool Softeners Saline Stimulant Osmotic Generic Name Brand Name(s) Methylcellulose Citrucel® Polycarbophil FiberCon®, Fiber-Lax® Psyllium Metamucil®, Konsyl® Glycerin Glycerin suppository (generic) Mineral oil Mineral oil (generic) Magnesium hydroxide (milk of magnesia) and mineral oil Phillips’® M-O Docusate sodium Colace®, Dulcolax® Stool Softener, Phillips’ Liqui-Gels® Magnesium hydroxide (milk of magnesia) Ex-Lax® Milk of Magnesia Laxative/Antacid Phillips’® Chewable Tablets Phillips’® Milk of Magnesia Bisacodyl Ex-Lax Ultra, Dulcolax Bowel Prep Kit Sodium bicarbonate and potassium bitartrate Ceo-Two Evacuant® Sennosides Ex-Lax® Laxative Pills Castor oil Purge® Senna Senokot® Polyethylene glycol 3350 GlycoLax®, MiraLAX Lactulose Kristalose® Bulk Laxatives: Review of Efficacy Laxative Psyllium Studies • 5 RCTs: – 3 placebo controlled – 1 well designed Bran • 3 RCTs: – 1 placebo controlled – All poorly designed Evidence • 2 trials: greater stool frequency, better stool consistency, and greater ease of defecation Summary and Recommendation Psyllium appears to improve stool frequency and consistency • 1 trial: no improvement • Stool frequency was significantly greater with bran than placebo if placebo was given first, but not if bran was given first Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S5-S21. GRADE B Insufficient data to make a recommendation Stool Softeners and Stimulant Laxatives: Review of Efficacy Laxative Docusate Studies • 4 RCTs: – 2 placebo controlled – 3 well designed Stimulant laxatives • 4 RCTs: – None placebo controlled – Low-quality study design Evidence Summary and Recommendation • 1 trial: greater stool frequency Insufficient data to make recommendation • 1 trial: greater stool frequency and global symptom assessment Docusate may be inferior to psyllium in increasing stool frequency • 2 trials: no improvement (1 vs placebo, 1 vs psyllium) • In 3 studies, no difference Not possible to make a between stimulant laxative recommendation about and control in stool frequency efficacy or consistency • 1 trial: less efficacy compared with lactulose at increasing stool frequency RCT = randomized controlled trial Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S5-S21. Osmotic Laxatives: Review of Efficacy Laxative Lactulose Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Studies • 3 RCTs: Evidence • All trials favor lactulose – All placebo controlled • Significantly improved stool consistency – 2 well designed • Mean number of BM/day significantly greater vs placebo • Increased stool frequency and improvement in stool consistency vs. placebo • 5 placebocontrolled RCTs • 2 RCTs comparing PEG and lactulose • Stool frequency greater, straining less often, overall effectiveness higher vs. lactulose Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S5-S21. Summary and Recommendation Effective at improving stool frequency and stool consistency GRADE A Effective at improving stool frequency and stool consistency GRADE A PEG 3350 – 12-Month Study An Open-Label, Single Treatment Multi-Centre Study of 311 Patients (117 aged 65 and older) 100 completely relieved somewhat relieved unchanged Percentage of Patients 90 80 70 60 46 50 52 49 50 40 40 30 20 10 0 Visits 16 15 14 11 10 4 3 3 1 1 2 months N = 250 4 months N = 217 6 months N = 203 9 months N = 185 12 months N = 180 PEG 3350 was determined safe and effective for treating constipation in adult older patients for periods up to 12 months, with no signs of tachyphylaxis Di Palma J. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;25;703-708. Adverse Effects of Laxatives • Bulking agents – Bloating – Severe adverse events: esophageal and colonic obstruction, anaphylactic reactions • Osmotic laxatives – Possible electrolyte abnormalities, hypovolemia – Diarrhea (2% to 40% of PEG-treated patients) – Excessive stool frequency, nausea, abdominal bloating, cramping, flatulence • Stimulant laxatives – Abdominal discomfort, electrolyte imbalances, allergic reactions, hepatotoxicity Brandt LJ, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S5-S21. Dangers of Saline Laxatives in the Elderly • Oral sodium phosphate products [Visicol®, OsmoPrep®, Fleet* Phospho-soda] for bowel cleansing • Black box warning for Visicol®, OsmoPrep® • Acute phosphate nephropathy • Patients with identifiable risk factors – – – – – Age > 55 Baseline kidney disease Hypovolemic, reduced intravascular volume Bowel obstruction, active colitis Using medications that affect renal perfusion or function *Withdrawn from the market Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/OSP_solution/default.htm. Accessed April 2009. Are Patients Satisfied With Laxatives and Fiber? Dissatisfied Patients (%) 100 OTC laxatives (n = 146) Prescription laxatives (n = 42) 80 71 75 Fiber (n = 268) 80 79 66 67 60 60 50 50 52 50 44 40 20 0 Ineffective Relief of Constipation Ineffective Relief of Multiple Symptoms Lack of Predictability Johanson JF and Kralstein J. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599-608. Ineffective Relief of Bloating Lubiprostone: A Chloride Channel Activator • Gastrointestinal-targeted bicyclic functional fatty acid • Activates ClC-2 chloride channels – Movement of Cl-, Na+, H2O follow – Increased luminal fluid secretion – Shortened colonic transit time • Indicated for: – Treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation (24 µg BID) in the adult population including age > 65 years (FDA approval 2006) – Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (8 µg BID) in women ≥ 18 years (FDA approval 2008) Cuppoletti J, et al. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1173-C1183. Amitiza PI. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2008/021908s005lbl.pdf. Accessed April 2009. Lubiprostone: Stool Frequency in Patients Over 65 with Chronic Constipation Nonelderly lubiprostone 48 µg Elderly (≥ 65 years) lubiprostone 48 µg Nonelderly placebo Elderly placebo Change from Baseline in SBM Frequency 6 5 * * † * † * *P ≤ 0.03 †P < 0.0001 † 4 N = 57 (patients aged ≥ 65 years vs placebo) 3 2 1 0 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 SBM = spontaneous bowel movement Ueno R, et al. Annual Meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology; October 2006; Las Vegas, NV. Johanson J, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:170-177. Safety Profile of Lubiprostone • Well tolerated in 4 week and 6-12 month trials • Nausea, diarrhea, and headache • No clinically significant changes in serum electrolyte levels • Low likelihood of drug-drug interactions – Non-absorbed; works intraluminally and does not result in measurable blood levels Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2008/021908s005lbl.pdf. Accessed April 2009. Suggested Management Algorithm for Chronic Constipation Bleeding, anemia, weight loss, sudden change in stool caliber, abdominal pain Alarm Symptoms Directed testing Refer to a specialist as needed No Alarm Symptoms Lifestyle, OTC, stimulant laxative No Response + Response Trial of lactulose or PEG 3350 No response + Response Trial of lubiprostone No response + Response OTC = over-the-counter therapies (probiotics, herbal medications, stool softeners [docusate sodium], psyllium, methylcellulose, calcium polycarbophil, bisacodyl, senna) Continue regimen Treatment for IBS-C Treatment Recommendation Psyllium Moderately effective; single study reported improvement with calcium polycarbophil Wheat or corn bran No more effective than placebo in relief of global IBS symptoms; Not recommended for routine use Polyethylene glycol Shown to improve stool frequency, but not abdominal pain in 1 small study No publications of placebo-controlled, randomized studies of laxatives in IBS-C Antibiotics Short-term course of a non-absorbable antibiotic is more effective than placebo for global improvement of IBS and for bloating. No data to support long-term safety and effectiveness Probiotics In single organism studies, lactobacilli do not appear effective for patients with IBS; bifidobacteria and some probiotic combinations demonstrate some efficacy ACG IBS Task Force. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:S1-S35. Treatment for IBS-C Treatment Antispasmodics (hyoscine, cimetropium, pinaverium, peppermint oil Recommendation Certain antispasmodics may provide short-term relief of abdominal pain/discomfort Evidence for long-term efficacy is not available; safety and tolerability evidence is limited Lubiprostone 8 µg BID is more effective than placebo in relieving global IBS symptoms in women with IBS-C Tricyclic antidepressants Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms; Appear to reduce abdominal pain Limited data on safety and tolerability Tricyclic antidepressants may worsen constipation Psychotherapy Cognitive therapy, dynamic psychotherapy, hypnotherapy (not relaxation therapy) are more effective than usual care in relieving global symptoms of IBS ACG IBS Task Force. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:S1-S35. Lubiprostone for IBS-C Data From 2 Phase 3 Studies Placebo N = 385 Lubiprostone (8 µg BID) N = 769 Response Rate (%) 20 15 P = 0.001 Note the different dose! For chronic constipation lubiprostone: 24 µg BID 10 5 0 Combined intent to treat population Monthly responder for ≥ 2/3 months during treatment Drossman D, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341. Lubiprostone – Symptom Change IBS-C Mean Change from Baseline Baseline Score 2.08 0 2.19 2.19 2.76 2.33 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 * -1.0 -1.2 -1.4 * Abdominal Discomfort/Pain§ §Score: †Score: * Bloating§ * * Constipation Severity§ Stool Consistency† 0 (absent); 1 (mild); 2 (moderate); 3 (severe); 4 (very severe) 0 (very loose/watery); 1 (loose); 2 (normal); 3 (hard); 4 (very hard/little balls) Drossman D, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341. Straining§ Nonresponder Responder * P < 0.001 When to Change/Add Therapy for an Unresponsive Patient? • No studies have examined this question1 • Stepped Treatment Of Older adults on Laxatives (STOOL) trial was designed to investigate the efficacy of adding a second agent when the first constipation therapy failed2 – It closed early with only 19 enrolled participants • In general, the prescribing clinician may elect to combine therapy depending on the patient’s response and lingering symptoms; recommended more often for patients with severe symptoms • Combine agents with different mechanisms of action, such as lubiprostone with senna, or an antispasmodic with a laxative for IBS-C 1. Gartlehner G, et al. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bookres.fcgi/constip/pdfconstip.pdf. 2007. Accessed April, 2009. 2. Mihaylov S, et al. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12(13). Post-Stroke Patient Special Considerations • Recent studies have reported constipation in 55% of patients at the acute stage (4 weeks)1, and in 30% ≥ 3 months2 following stroke • Patient limitations – Positioning problems – Reduced peristalsis – Immobility Treatment Strategy* 1. Appropriate assessment of bowel function, frequency, consistency 2. Tailor a specific bowel management program to facilitate/initiate defecation 3. Careful documentation with a bowel diary 4. Glycerin suppositories, laxatives, motility agents to promote defecation *Treatment strategy based on clinical experience 1. 2. Su Y, et al. Stroke. 2009;40:1304-1309. Bracci F, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(29):3967-3972. Patient With Dementia Contributing Factors • • • • • • • • • • Immobility Dehydration Inadequate food intake Depression Cognitive deficits Cannot find the bathroom Inability to undress Cannot ask for help Cannot sense the urge to defecate Use of psychotropic drugs Treatment Strategy* 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Appropriate assessment of bowel function Establish a bowel routine, regular toileting program Suppositories, stool softeners, bulking agents Careful documentation (bowel diary, effectiveness of treatments, etc.) Involve family or health care team (in a nursing facility) Address nutritional/fluid needs *Treatment strategy based on clinical experience Patients Treated With Opiates Special Considerations • Opioids inhibit GI propulsive motility and secretion • GI effects of opioids are mediated primarily by µ-opioid receptors within the bowel • Constipation is a common and troubling side effect • Patients do not develop tolerance to the effects of opiates on the bowel Treatment Strategy* 1. Laxative therapy should be initiated proactively with start of opiate use 2. Magnesium hydroxide, senna, lactulose, bisacodyl, stool softener 3. A combination of a stimulant and stool softener is often required 4. Laxative doses may need to be increased along with increased doses of opioids 5. Titrate doses of laxatives according to response prior to changing to an alternative laxative 6. When laxative therapy is inadequate, consider methylnaltrexone *Treatment strategy based on clinical experience Tamayo A, Diaz-Zuluaga P. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:613-618. Shaiova L, et al. Palliat Supp Care. 2007;5:161-166. A Role for Peripheral µ-opioid Receptor Antagonists? • Methylnaltrexone – Novel, quaternary µ-opioid receptor antagonist – Does not antagonize the central (analgesic) effects of opioids or precipitate withdrawal – FDA approved for treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced illness, receiving palliative care, when laxative therapy has been inadequate – Subcutaneous injection; one dose (0.15 mg/kg) every other day as needed, no more than 1 dose in a 24 hr period – Abdominal pain and flatulence most common adverse events Foss JF. Am J Surg. 2001;182 (5ASuppl):19S-26S. Thomas J, et al. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:2332-2343. Relistor [package insert]. Available at: http://www.wyeth.com/content/showlabeling.asp?id=499. Accessed April 2009. Neurologic Disorders: Parkinson’s Disease Special Considerations • Constipation occurs in at least 2/3 of patients • Multifactorial: – Slow colonic function – Defecatory dysfunction – Enteric and central nervous system – Antiparkinsonian medications Anticholinergic agents Dopaminergic agents • Underlying illness is chronic and uncorrectable Treatment Strategy* 1. Adjust medications if possible 2. Initiate pharmacologic therapy – May need to use medications from several classes – Osmotic laxatives, Cl channel activators, stimulant laxatives *Treatment strategy based on clinical experience Stark ME. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:567-574. Chronic Constipation Secondary to Diabetes Special Considerations • Constipation occurs in 20% of patients with diabetes • Related to duration of diabetes > 10 years • Diabetic autonomic neuropathy • Gastrocolic reflex may be absent, delayed, blunted • Constipation may be severe and can lead to megacolon Treatment Strategy* 1. Optimize diabetes care 2. Stepwise pharmacologic therapy – Exclude slow transit – Bulking agents, osmotic laxatives, Cl channel activators, stimulant laxatives *Treatment strategy based on clinical experience Verne GN, et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27:861-874. Complications of Chronic Constipation • Fecal impaction1,2 – Identified in up to 40% of elderly adults hospitalized in United Kingdom • Intestinal volvulus/obstruction2 • Urinary and fecal incontinence2 • Stercoral ulceration/ischemia2 • Bowel perforation2 • Possible increased risk of colorectal cancer (controversial)3,4 1. 2. 3. 4. Read NW, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:61-70. De Lillo AR, Rose S. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:901-905. Roberts MC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:857. Dukas L, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:958-964. Fecal Impaction Recognition/Identification • Maintain high level of vigilance for institutionalized patients or patients in the hospital – Absence of bowel movement, absence of bowel sounds – Fecal soiling, fecal incontinence of liquid stool • Assessment – Digital rectal exam – Abdominal x-ray Treatment Strategy* 1. Prevention!! 2. Treat from below • Enema, suppository • Manual disimpaction with prior pain medication 3. Treat from above • Osmotic laxatives 4. Institution of preventative measures • Diet, laxatives, bowel regimen *Treatment strategy based on clinical experience Emerging Therapies Prucalopride – – – – Selective 5-HT4 agonist Does not interact with 5-HT3 or 5-HT1B receptors Increases colonic motility and transit Phase 3 studies have demonstrated efficacy of 2 or 4 mg prucalopride in patients with severe chronic constipation – Adverse events included headache, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea Linaclotide – Guanylate cyclase agonist – Induces intestinal fluid secretion – Pilot study showed improved spontaneous bowel movement frequency and improved symptoms in patients with chronic constipation – Also being studied in patients with IBS-C Camilleri M, et al. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344-2354. Quigley E, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:315-328. Tack J, et al. Gut. 2009;58:357-365. Johnston J, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:125-132. Myths and Misconceptions About Chronic Constipation Misconception Reality Diseases arise from autointoxication by retained • No evidence to support this theory stools Fluctuations in hormones contribute to constipation • Fluctuations in sex hormones during the menstrual cycle have minimal impact on constipation, but are associated with changes in other GI symptoms • Changes in hormones during pregnancy may play a role in slowing gut transit A diet poor in fiber causes constipation • A low fiber diet may be a contributory factor in a subgroup of patients with constipation • Some patients may be helped by an increase in dietary fiber, others with more severe constipation may get worse symptoms with increased dietary fiber intake Increasing fluid intake is a successful treatment for constipation • No evidence that constipation can be treated successfully by increasing fluid intake unless there is evidence of dehydration Muller-Lissner S, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:232-242. Heitkemper M, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):420-430. More Misconceptions About Chronic Constipation Misconception Reality Stimulant laxatives damage the enteric nervous system and increase the risk of cancer • Unlikely that stimulant laxatives at recommended doses are harmful to the colon • No data support the idea that stimulant laxatives are an independent risk factor for colorectal cancer Laxatives cause electrolyte disturbances • Laxatives can cause electrolyte disturbances, but appropriate drug and dose selection can minimize such effects Laxatives induce tolerance • Tolerance is uncommon in most laxative users, however tolerance to stimulant laxatives can occur in patients with severe constipation and slow colonic transit Laxatives are addictive • No potential for addiction to laxatives, but laxatives may be misused Muller-Lissner S, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:232-242. Patient and Caregiver Education • Provide reassurance • Engage patients/caregivers in a discussion of constipation • Discuss medicines that can contribute to chronic constipation • Discuss criteria for diagnosis, share a diagnostic algorithm • Utilize patient questionnaire/symptom log • Discuss treatment options, including – Common side effects – How long a treatment might take to work – Is it appropriate to request an alternative treatment? • Answer questions! • Emphasize the goals of treatment – Improve symptoms – Restore normal bowel function – Improve quality of life Summary • Chronic constipation is a common condition in the elderly • Quality of life in elderly patients is negatively affected by the symptoms of chronic constipation and IBS-C • Identify risk factors and secondary causes for constipation • Be vigilant for red flags or alarm symptoms; directed tested may be necessary • Main objective of treatment for chronic constipation is to improve patients’ symptoms, restore normal bowel function (≥ 3 bowel movements per week), improve quality of life Summary (cont) • Evidence-based therapeutic options for chronic constipation include psyllium, lactulose, polyethylene glycol, and lubiprostone • Psyllium, polyethylene glycol, antibiotics, probiotics, antispasmodics, antidepressants, lubiprostone and psychotherapy are treatments for IBS-C with varying degrees of efficacy • Long-term safety and efficacy data needed for therapeutic options for both chronic constipation and IBS-C, particularly in older (> 65) adults • Careful recognition, assessment, treatment, and monitoring can lead to more effective patient-specific interventions that can reduce the burden of chronic constipation or IBS-C