Chapter 8

advertisement

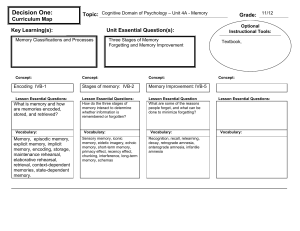

Chapter 8 Memory Slide 1 What is Memory? Often when we use the word “memory” we are referring to the conscious recollection of some past experience. e.g., What did you wear yesterday? However, in Psychology, we define memory much more generally. My definitions would go something like: Memory influences are any influence by which past experiences affect current performance. Given this more broad definition, there may be a large number of ways in which memory can influence us … for example: Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 2 Alphabetic Arithmetic Example • • • • • • • • Chapter 8 – Memory A+3=D C+2=F T+2=W A+3=D S+3=V C+2=F S+3=V T+2=W • • • • • • • • C+2=F S+3=V A+3=D T+2=W A+3=D C+2=F S+3=V T+2=W Slide 3 Rough Processing Model of Memory Stimulus Chapter 8 – Memory Sensory Memory aka, iconic or echoic memory Working Memory aka, short-term memory Long-Term Memory aka, memory Slide 4 Sensory Memory Often a “sensory trace” or the stimulus remains after the stimulus is gone. These traces are termed sensory memory, and they tend to be very short-lived. Sensory memory was most extensively studies by a cognitive psychologist named Sperling. Sperling’s studies focused on visual sensory memory which he termed iconic memory … here’s how they worked. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 5 Iconic Memory - Full Report Condition Nine items will briefly be presented in the box below, then they will disappear. How many can you remember? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 6 Iconic Memory - Full Report Condition Nine items will briefly be presented in the box below, then they will disappear. How many can you remember? Chapter 8 – Memory K L W D S P H J A Slide 7 Iconic Memory - Full Report Condition What was your subjective impression? Did you think you saw them all for a short while … then they faded away? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 8 Iconic Memory - Partial Report Condition This time, report only the row that is indicated by the arrow that comes up after the letters are gone. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 9 Iconic Memory - Partial Report Condition This time, report only the row that is indicated by the arrow that comes up after the letters are gone. Chapter 8 – Memory S J U B M Q A R P Slide 10 Iconic Memory - Partial Report Condition If we multiply your number recalled here by 3, we likely get a larger number than your full report number, right? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 11 Echoic Memory There is also an auditory version of sensory memory that is called echoic memory. You likely have noticed this form of memory in action. For example, the “what? effect”. As a further example, Steve will now do an auditory demonstration of echoic memory … his so called “5-3-5-7-2-stop” game. While iconic memory disappears in approximately 1 second, echoic memory seems to last about 4 seconds. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 12 Rough Processing Model of Memory Stimulus Chapter 8 – Memory Sensory Memory aka, iconic or echoic memory Working Memory aka, short-term memory Long-Term Memory aka, memory Slide 13 Short-Term or Working Memory Steve will now read out a set of numbers, try your best to remember them. That “process” you feel is something Cognitive Psychologists call working memory. As Steve will now demonstrate, this form of memory is fairly fragile and capacity limited. It seems to require a great deal of mental effort to keep things in working memory and, once the leave, they are gone. Sometimes we use this memory for short-term storage, though it also seems necessary for transferring info to long-term mem Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 14 The Relation Between Working Memory and Long-Term Memory The purpose of Working Memory is not to simply transfer information into long-term memory. In fact, some would argue that working memory is what we sometimes call “thinking” and long-term memory clearly enters into it. Try some of the following: > D+6=K, true or false? > 5 X 13 = ? > Imagine yourself sitting on a camel, how high could you reach? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 15 Primacy and Recency Effects Primacy Effect Probability of Recall If I gave you a long list of words to remember, then asked you to just recall all the words you remember, you would likely remember words at the beginning and end of the list best. 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 Recency Effect 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Serial Position The primacy effect is typically attributed to additional rehearsal of items earlier in the list - Long-term Memory. In contrast, the recency effect is typically attributed to either short-term memory readout or even echoic memory. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 16 How long do things stay in Working Memory? If a person is allowed to rehearse, information will stay in working memory for as long as it is rehearsed. In their experiment, rehearsal was prevented by making subjects count back from some number by threes while remembering letter trios (e.g., JDK, LPD) Chapter 8 – Memory Probability of Re call However, if not allowed to rehearse, Peterson & Peterson (1959) showed that information 1 decays from working memory fairly quickly. 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 3 6 9 12 15 Time (seconds) Slide 17 How are things lost from Working Memory So, this disappear quite quickly from working memory if they are not rehearsed … what makes them disappear? One possibility is that the items just decay over time. This second possibility seems most reasonable given the data to the right. Chapter 8 – Memory 100 Pe rce ntage Corre ctll A second possibility is that new items coming into working memory actually “push out” things currently in it. 80 1/Sec 60 4/Sec 40 20 0 1 3 5 7 9 11 Intervening Items Slide 18 The Capacity of Working Memory As we already discussed, working memory has a limited capacity. Specifically, the limit seems to be 7 plus or minus 2 chunks. What is a chunk? Time for another memory experiment! Hopefully the demo showed that we can greatly increase our ability to keep things in working memory by chunking the information. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 19 Rough Processing Model of Memory Stimulus Chapter 8 – Memory Sensory Memory aka, iconic or echoic memory Working Memory aka, short-term memory Long-Term Memory aka, memory Slide 20 Long-term Memory So, a simplistic view on what we’ve said so far is that things that are rehearsed enough end up being stored in long-term memory. Things that are not rehearsed are not. This transfer of items from working memory to longterm memory is called consolidation, and the theory of consolidation is primarily supported by concussion studies (e.g, the football example). However, this simplistic view is not sufficient. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 21 Depth of Processing - Shallow • • • • • • • • • Chapter 8 – Memory flame patch sonic bless fleet pears spade bliss forth • • • • • • • • • peels speed block freak pints spice blush frost pluck Slide 22 DOP - Shallow - Recall Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 23 Depth of Processing - Deep • • • • • • • • • Chapter 8 – Memory spoon bonds glass ports spray boots goose prize steam • • • • • • • • • brand grass quart stink bride green queen story brown Slide 24 DOP - Deep - Recall Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 25 Depth of Processing - Overview Clearly then, the way that you rehearse information effects the likelihood that the information will enter long-term memory. Elaborative rehearsal (i.e. deep) tends to produce superior memory on conceptual tasks like most memory tasks. Maintenance rehearsal (what we typically do when trying to remember a phone number for a little while) is not nearly as good at transfering info to long-term memory. Thus, let us re-visit our “attractive person gives you phone number when you do not have paper” example. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 26 Learning Without Rehearsal As the depth of processing section demonstrates, we can learn things via elaborative rehearsal … this type of process is sometimes referred to as an effortful process. However, we often remember things that we did not rehearse in an effortful manner. The formation of memories for things we did not perform effortful processing on is called automatic processing. The exact processes underlying automatic transfer to longterm memory are still largely unknown but its very existence challenges a simple consolidation view. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 27 Improving Your Memory via Mnemonics Given all these studies of memory, what have we learned about improving memory skills? Techniques used to improve memory are called mnemonic strategies and, as the name implies, typical involve some form of effortful processing. We’ll consider three techniques: (1) the method of loci, (2) the peg-word method, (3) creating a narrative, and (4) creating acronyms Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 28 The Method of Loci In a country far far away (Greece), at a time long long ago (sixth century BC), oratory skills were prized, and paper was rare (OK, it didn’t exist). Orators had to come up with ways to memorize long speeches. They devised the method of loci. This method simply involves forming an image of some route you are familiar with (say the drive to Scarbra), and then “placing” images of the concepts you want to remember along this route. Then, by retracing the route in your head and examining the images, you can reconstruct the concepts in order. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 29 The Peg-Word Method This method is similar to the method of loci except, instead of putting images along a route, you associate them (via imagery) with nouns that rhyme with the numbers. The typical ones: one: two: three: . 32: Chapter 8 – Memory bun + image representing concept 1 shoe + image representing concept 2 tree + image representing concept 3 dirty shoe + image representing concept 32 Slide 30 Other Techniques Another way of remembering a list of items is to create a story (or song) that links the concepts together in some ordered manner - this is called forming a narrative. Yet one more method is to form an acronym that represents the concepts you want to remember: Roy G. Biv The A.B.C.s of first aid. Begin With Review And Friend or Big Women Really Are Fun! Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 31 Memory, One Structure or More? Currently, one of the debates in memory concerns whether we have a single, or multiple long-term memory systems. Those who believe in multiple memory systems typically talk about things like the following: Episodic Memory - Our memory of very specific events in our lives … tends to contain rich detailed info. E.g. - What did you do last night? Semantic Memory - Our general world knowledge. E.g. - What city is the capitol of Manitoba? Procedural Memory - Our memory of how to do things. E.g. - How to ride a bike, or kill without thinking. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 32 Implicit vs. Explicit Memory/Tasks Another distinction that is often made is the distinction between implicit and explicit memory. Implicit memory tasks are ones that test memory without specifically directing subjects to think about the study items. In contrast, explicit memory tasks do direct the subject to try and use study items when completing the memory test. Implicit and explicit memory are the memory structures these tasks are thought to tap. An example if you please ... Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 33 Implicit/Explicit Example Graf & Mandler (1984) showed subjects lists of words and ask them either to perform “deep processing” (how much do you like the word) or “shallow processing” (how many letters does the word have) on them Chapter 8 – Memory 45 40 Precent Recalled The subjects were then shown stems corresponding to the items (e.g., spice --> spi__) and were given either implicit (complete with the first word that comes to mind) or explicit (complete with a study item) instructions. Explicit Implicit 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Deep Shallow Slide 34 The Biological Basis of Memory So how does this all relate to the brain? Most of what we know about the biological basis of memory comes from research in two areas: (1) Neuropsychological studies of human braindamaged patients. (2) Psychophysiological studies with animals Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 35 Neuropsychological Studies There are generally two types of memory impairments that can occur as a result of brain damage: Retrograde amnesia refers to the condition where patients cannot remember events that occurred prior to the head trauma. Most recent events are the most likely to be lost, and the amount of loss can be from minutes to years. Anterograde amnesia is a condition wherein patients can remember past events just fine, but they have an inability to form new long-term memories … some types at least. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 36 H.M. & Alcoholics One of the most influential cases of anterograde amnesia was the case of H.M., a patient who underwent bi-lateral removal of his hippocampus and amygdala to treat severe epilepsy. The good news is, his epilepsy was cured. The bad news is, he ended up with a very profound case of anterograde amnesia. This condition also is a common result of a form of alcoholism termed Korsokoff’s syndrome. Some alcoholics get all their nourishment from the liquor, causing vitamin deficiency. A lack of one vitamin in specific leads to profound anterograde amnesia. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 37 What is lost and what is not? Patients with anterograde amnesia do have memory for events that occurred prior to the trauma, so clearly they have an intact memory retrieval system. Thus, it seems their real problem is in storing new memories … but not all kinds of new memories, just episodic memories it seems. 60 Control 50 Amnesic 40 30 20 10 0 Explicit Implicit Thus, the hippocampus appears critical for the formation of episodic memories Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 38 Psychophysiological Studies Critters also appear to form episodic memories which help them to do things like remember locations where they have already searched for food. If their hippocampus is destroyed, they also appear to suffer from the loss of episodic memory. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 39 Summary of Long-Term Memory So Far So we know that there are a number of ways things can get into long-term memory, and various strategies can be used to facilitate this process. We also know that there at least seems to be different types of long-term memory and episodic memory seems to be the most fragile of these. Finally, we also know that the hippocampus appears critical for the formation of new long-term episodic memories, with destruction of the hippocampus leading to anterograde amnesia. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 40 Remembering Generally, psychologists believe that the actual process of retrieving information from memory is an automatic process. An automatic process is one that: (a) is carried out very quickly (b) is not under the control of consciousness (c) does not interfere with other ongoing processes Things are assumed to become automatic via a process of overlearning … the assumption being that if some process is performed over and over again, it will become automatic Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 41 Reading as an Automatic Process As an example of an automatic process, remember the Stroop experiment we did early in the year? RED GREEN BLUE GREEN GREEN RED RED BLUE BLUE BLUE GREEN RED RED GREEN BLUE BLUE RED GREEN BLUE GREEN GREEN RED RED BLUE BLUE BLUE GREEN RED RED GREEN BLUE BLUE Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 42 The Importance of Retrieval Cues If retrieval from memory is automatic, why does it sometimes seem so effortful to retrieve something from memory? For example, the tip of the tongue phenomenon Retrieval is automatic IF useful retrieval cues are present in the environment. The effortful part of retrieval is trying to come up with effective retrieval cues that will make retrieval happen. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 43 Tranfer-Appropriate Processing The most effective retrieval cues are those that, in some manner, re-create part of the original learning environment. The importance of recreating the learning environment was first shown in what may be the only (so far) psychology experiment with SCUBA divers. That is why when you lose something people will often suggest that you “retrace your steps” from some point in time when you had that thing. It is also related, but not identical, to the concept of statedependent learning. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 44 Decay from Long-Term Memory Often students feel like they study hard for an exam and, as soon as the exam is complete, the information they studied is gone! Is it? How long does information stay in memory, and how can we scientifically study memory decay? This issue was first addressed by Ebbinghaus (1895) and his results and techniques are still interesting. Ebbinghaus taught himself thirteen nonsense syllables (e.g., dax, wuj) and then tested his memory after various delays. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 45 Percent Recalled Ebbinghaus’ Results and Real World 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 15 20 25 30 Days since learning Ebbinghaus’ work suggests we retain some of the info for at least 30 days, even when it has no meaning. Similar “real world” studies suggest that we can retain information we learned over 40 years ago or more. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 46 Relearning: Gone but not Forgotten Ebbinghaus also showed that even when information feels like it has been lost from memory, it is still there. He demonstrated this using a relearning task in which he had to relearn a list he had already studied a long time ago. Even when he felt that the information had been completely lost from memory, it took him less time to relearn that information than it had the first time. So, even though you think you forget stuff after you write your exam, it is still there, and you will be able to get it back quickly if you should ever need to. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 47 Remembering: Part Fact, Part Fiction When we remember something, some of what we remember is fact, and some is a reconstruction that fits with our ideas of the world and our current context. How about an experiment? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 48 Remembering: Part Fact, Part Fiction When we remember something, some of what we remember is fact, and some is a reconstruction that fits with our ideas of the world and our current context. How warm was it yesterday? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 49 Remembering: Part Fact, Part Fiction When we remember something, some of what we remember is fact, and some is a reconstruction that fits with our ideas of the world and our current context. How cold was it yesterday? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 50 Remembering: Part Fact, Part Fiction What we seem to do is remember only certain details that we experienced, then, while remembering, we create a “story” that includes these details. The “story” we create is biased by a number of things including (a) the current context including the question that lead to recounting, (b) a desire to tell a coherent, sensical story, (c) our current mental state and beliefs. Moreover, the confidence we have in our memories seems largely unrelated to the accuracy of those memories, often we are most confident in the “memories” we created. Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 51 A Final Experiment (for now) SLEEP HAMMER CHAIR TETINUS STICHES Chapter 8 – Memory YARN PILLOW THIMBLE CACTUS DREAM PINK MATRESS SHOT SHEET NIGHT THREAD TIRED BLANKET CANDLE PIERCE Slide 52 A Final Experiment (for now) PINK? CANDLE? Chapter 8 – Memory NEEDLE? TICKET? ROSE? BED? WATCH? BOOK? Slide 53 A Final Experiment (for now) SLEEP HAMMER CHAIR TETINUS STICHES YARN PILLOW THIMBLE CACTUS DREAM PINK MATRESS SHOT SHEET NIGHT THREAD TIRED BLANKET CANDLE PIERCE PINK? CANDLE? NEEDLE? TICKET? ROSE? BED? WATCH? BOOK? Chapter 8 – Memory Slide 54