Balance is with strengthening muscles that are

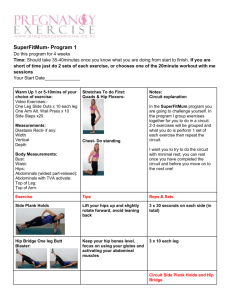

advertisement

Strengthening from the core down & weakness of muscles relative to the rest of the

body

What is important to understand is that none of these exercises are intended to isolate a

particular muscle since this is extremely rare in nature. Instead, a set of muscles are engaged

to do the drill.

Leisman, et al (1995) have provided the first electrophysiologically based definition of what

AK practitioners observe as conditionally facilitated and inhibited muscle responses to manual

muscle testing procedures: The “ability or inability of a muscle to lengthen but also generate

enough force to overcome resistance is what is qualified by the examiner and termed “Strong”

or “Weak.”

A weak muscle - meaning underdeveloped - may have perfect neurological feedback and

therefore only needs to be strengthened with conventional exercises. However, if a muscle

is inhibited, it means that the muscle does not have a proper neurological connection.

Therefore, it cannot be strengthened through conventional forms of exercises until

the muscle has been activated or jumpstarted. This is why we call an inhibited muscle

neurologically weak. When a muscle is inhibited, it means that the connection between the

brain and the muscle - via the central nervous system - is impaired. Isometric exercises are

designed to "jumpstart" or stimulate the relationship between the muscle and the brain. It's

like tightening the battery cables on your car. The goal is to utilize all of the electrical

impulses being transmitted to the muscle. By "tightening the cable" or "jumpstarting" the

muscle, the end result is increased contractile capabilities of the muscle. If your muscle is

neurologically weak, then strength training will only reinforce the imbalance. It is entirely

possible for someone to have inhibited muscles for many years.

What is considered as weakness

Weakness in a muscle that is not yet strong enough to carry a certain amount of force. It is

only weak relative to the amount of work it is being given. Muscles are injured because the

force on them is greater than their inherent strength, so they start to tear

or

weakness as relatively weak or underused, compared to other muscles (often due to poor

technique in training and habitual movement patterns that create strength imbalances)

or

weakness in not receiving the proper neurological input (not enough/none at all).

etc.

A Word On Testing Muscles

Note also that it is possible to pass all these tests with flying colors and still have substantial

imbalances. The tests will identify EXTREME weaknesses or imbalances, but often

imbalances are relative. Thus, you may appear to have decent glute activation, ab strength,

and hip flexor length when tested on an isolated test, but you may find that one more more

aren't quite as strong as the others.

Source: http://www.higher-faster-sports.com/noglutes.html

Runner’s World: “If an exercise requires several muscles to perform the movement, the

majority of the work will be done by the strongest of those muscles.”

Attaining good form by strengthening all relevant muscles (and equally) and

preventing injury.

When not exercising…

- Work on breathing from the belly, NOT the chest

- Move around with your weight backwards

- Move around using your hamstrings more.

3.1 Stage one

All the below involve supporting weight on one leg, just as it is during the running stride.

They should be undertaken without shoes on and obviously be repeated for both legs!

Gluteus- bum

When you stand on one leg, your opposite gluteus muscle works to prevent your hip

dropping. If your hip drops this may force rotation of the leg, thus the hip, knee and toe are

not in line. Therefore, the first exercise is to strengthen the gluts standing against the wall:

Stand with your feet parallel to the wall ten inches apart, with the foot closest to the wall

almost touching it. Lift the knee of the leg closest to the wall so the thigh is horizontal, then

bend the outer leg slightly and press the inner thigh onto the wall still holding it horizontal.

Hold this position, focusing on pressing the knee against the wall into the wall.

This should be practised until the position can be held for 5mins.

Lower Leg

The next set of exercises focuses on strengthening the lower leg muscles which stabilise the

leg through the stride. All exercises should be undertaken with hip, knee and toe in line

vertically.

Balance on one foot, then:

1.

With foot flat on floor, bend and straighten leg at the knee maintaining balance.

2.

Balancing on ball of foot, bend and straighten leg at the knee maintaining balance.

3.

With leg bent at the knee, raise foot from flat onto balls of feet and back again.

4.

Hop up and down as high as you can, land on the balls of your feet and aim to land on

the same spot, maintaining balance. For all the above try to reach 3x15-20 with 60 sec rest.

Focus on the ones you find difficult if you’ve mastered the easy ones.

5.

With leg bent at the knee, rotate hips from furthest left position to furthest right ~160

degrees and back, whilst keeping knee and toes aligned in the initial direction. Practice until

you can maintain your balance and then try balancing on the balls of your feet.

The above exercise aims to strengthen and coordinate muscle groups, so that rotation of the

hips about a vertical axis is independent from swinging of leg.

From the site:

http://www.cuhh.org.uk/linksandresources/RunningSpecificStrengtheningExercises.pdf

How do you determine which muscles are weak?

Testing the muscle strength

As always with muscle testing, it can be difficult to be completely objective in the clinic without

lab equipment. But it is quite easy to gain valuable information to complement your dynamic

assessment.

My approach is threefold. Let’s imagine we are testing the right gluteus medius. First, I ask

the athlete to perform the ‘clam’ exercise. In left side-lying, both hips are flexed to 30 degrees

with knees bent and hips and feet stacked in line. The athlete has to open their knees while

keeping heels together, and most importantly, holding the pelvis completely still. I palpate the

gluteus medius for activation. If the pelvis moves despite education on positioning, it means

the athlete is unable to isolate the muscle and is trying to recruit ‘cheating’ muscles such as

TFL.

The second test is side-lying hip abduction, performed in the same position, but with the right

leg straight and in slight hip extension (i.e. just behind the line of the trunk). The athlete must

abduct the leg without hitching the right side of the pelvis (hip hitching would mean they were

concentrically recruiting quadratus lumborum and obliques), without falling into anterior pelvic

tilt and without letting the pelvis tip back. You can further test the strength of the muscle by

getting the athlete to resist your attempts to push the abducted leg downwards. Check for any

compensatory or cheating recruitment. To assess muscular endurance, ask the athlete to

hold the abducted leg steady for 30 secs.

Lastly I ask the athlete to perform a single- leg squat while I observe control at the foot, knee

and pelvis. This also gives me an idea of the stability of the whole lower- limb-to-pelvis chain.

All this should be compared to the uninjured side.

A Perspective on Strengthening Runners

> Anterior leg muscles

(To prevent shin splints)

> Quadriceps

(To prevent runner's knee)

> Hips and groin

(To prevent iliotibial band syndrome)

> Abdominal

(To prevent lower back pain)

> Lower back

(To prevent lower back pain)

“Obviously a stronger muscle is more difficult to injure”.

Joseph Coyne points the most important muscles to strengthen for running to be the

hamstrings as hip flexors, the hamstrings as hip extensors, the quads, the 3 lower extremity

accessory muscles he focuses on (the triceps surae, the tibialis anterior and the flexor

hallucis longus (FHL)), and the core (part of the trunk musculature).

EMG: There are actually studies that show squats replicate the EMG activity of high paced

running the closest out of any exercise. This includes single leg exercises, which I found

quite surprising. EMG measures the type, frequency and strength of muscular contractions

during exercise so squatting and running are actually very similar movements for our body.

Remember when strengthening: Speed is not your friend. You'll get the best results by using

slow, methodical movements instead of rapid, quick bursts of movement.

Chest out, always. Core tight.

Strengthening the QUADS for runners (also, the inside and outside of quads)

The Wall Sit (make sure burn is felt in the quads, glutes, hamstring)

- Stand with your back against a wall, placing your feet about two feet out in front of

you. Feet should be hip-distance apart.

- Bending your knees, slide your back down the wall until your knees are at 90 degree

angles. Your knee joints should be over your ankle joints, so you may need to inch

your feet further from the wall to create proper alignment. Your thighs should remain

parallel.

- Hold for 30 to 60 seconds, and then stand up. Repeat for a total of three reps.

Leg extension machine

Traditional Squat (make sure burn is felt in the quads, hamstring and glutes as primary,

and calves as secondary)

- Warm up with 5 minutes of cardio before you start!

- Stand with feet hip distance apart with your toes, knees and hips all in a straight line.

- Pull your belly button towards your spine and contract your abdominal muscles.

- Slowly lower your body, as though you are sitting in a chair.

- Breathe continuously and keep your neck in line with your spine.

- If you can, go down until your butt is in line with your knees (knees at 90 degree

angle). If you can't go down that low, go as low as you can.

- Take a moment and look down make sure your knees are BEHIND your toes.

- Engage your glutes to keep your knees for caving in.

- Keeping the weight in your heels, slowly push your body back to starting position.

- As you come back up, straighten the legs a little bit (instead of just rising up), then

once you feel that your pelvis can begin to tuck, you drive the hips forward with your

glutes.

- Pull your lower leg before you unsquat, to set the activation of the glutes.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FNHFuv-yBko&feature=related (Functional Patterns)

-

At the top of the movement, do NOT lock your knees. Keep a slight bend in them.

Engage your core to align your back. You need to develop awareness on whether

your lower back is slumping or arching.

-

-

Exercising with a curve in the back, especially under load, is heavily frowned upon in

weight training circles. You keep the back straight (in physiotherapy, ”straight” means

in one line, it does not imply vertical) in deadlifts and squats and don’t get into the

habit of having the spine curved.

Repeat the movement 10 to 15 times, performing 1 to 3 sets. For each repetition,

count to 3 on the way up and on the way down to ensure you're not going too fast.

Rest 30 to 60 seconds in between sets.

Stretch your quadriceps and hamstrings after each set or after your final set,

spending at least 10 to 15 seconds on each stretch.

Jump Squats (Plyo)

- Squat parallel then explode up, jumping at the end of the movement.

- Straight legs as you jump.

- Land with a slight bend in the knees.

- Lower yourself into the squat in a controlled manner.

A tip that hasn't been mentioned is curling your toes slightly when squatting. This will force

you to sit back into the squat, and not allow your knees to jut out past your toes.

Lunges (make sure burn is felt in the quads, glutes, hamstring), also known as the split

squat

A long lunge emphasizes the glutes and hamstrings whereas a short lunge emphasizes the

quadriceps. (Learn single leg balance since forward lunges balance on front leg, whilst

reverse lunges are already standing on the front leg)

- Big step forward. Little step means knees over toes and a weird back knee. The step

should be big enough to bring your back leg on full tippy-toes. Alternately, you

can step one foot forward and one foot back to get into position.

- Come into a kneeling lunge (with your back knee on the floor) and try to make a

straight line all the way from your shoulder down to your knee to determine the

appropriate length of your stance.

- Feet are hip-distance apart rather than lined up one in front of the

other (and not too far apart either).

- Make sure your torso doesn’t twist (make it visible) so that the knee

doesn’t track inward and your body twist unnaturally.

- Back leg is on full tippy-toes, note how a partial tippy-toe twists your torso. Fully tiptoeing keeps your torso straight ahead of you.

- Keep the front knee directly above your ankle.

- Shins vertical.

- Even though the front knee should not go past the toes, it should also not go behind

the ankle.

- Keep the weight of the front leg on the heel of the foot. Think of having your centre of

gravity in your front heel. Push off your front heel. Do not use your back leg to push

off.

- As you go up and down, the back foot should not rock back and forth.

- The burn must be felt on both legs, the back quad vertical to the ground.

- Engage the right muscles (glutes and abs) by contracting them consciously

(contract your abdomen in and up). Think of engaging your glutes to keep the knee

lined up over the ankle.

- Keep the abdomen engaged (but still breathe!) to keep your upper body straight.

- Feet stay about hip-width apart so that the hip, knee and ankle all stay aligned (make

your upper leg visible) as you go down.

- Make sure your torso isn’t twisted as you do the lunge (make your torso visible), so

the knee does not track inwards.

- Breathing: Inhale through the nose when you lunge down and exhale through the

mouth as you come back up.

Common mistakes:

- Leaning forward or to one side instead of keeping the upper body straight. Unlike

squats, your upper body stays vertical.

- Using momentum to lift your body, thus not completing the entire lunge

- Putting too much stress on the knee by letting it overlap past the toes

-

Looking down, causing a cramp in the neck

Letting the knees touch the ground instead of just coming close to it

Letting the quads and hamstrings do all the work, whilst not getting the glutes

involved

Correct

Incorrect

An order to strengthening muscles

[Making your quadriceps overactive (overtraining them)] causes your thighs to activate first

before your hips do in many movement patterns, such as squats and deadlifts, says physical

therapist Gray Cook, author of "Movement." Hyperactivity in your thighs inhibits your ability to

squat deep and strains your hip joints, knees and lower back. Cook suggests you strengthen

your buttocks and stabilizers deep in your abdominal muscles before you strengthen your

quadriceps.

Even runners with already strong legs tend to slightly favor one leg, and this can lead to a

disparity that can weaken performance and set you up for injury. The solution, says Plaatjes,

is to work each leg separately. When you do exercises like a squat using both legs, your

stronger side helps your weaker side, reinforcing the discrepancy. Performing single-leg

exercises forces the muscles to work on their own, and over time, the imbalances will even

out.

“For the lunge - reach out farther on your lunge step and your hamstrings will be worked

more than your quadriceps.”

Strengthening the GLUTES for runners

If muscles are weak, they should be activated first (before strengthening them).

Glute activation exercises (since the 3 gluteals each have different functions, they all need

different exercises to activate them, e.g. bridges for glute max, clam for glute med)

- The hip flexor/psoas stretch (Use this slow, static hip flexor stretch to help inhibit the hip

flexors, particularly the powerful psoas muscle, while you get your glutes firing)

- The Bridge (first and generally easiest way to get your glutes firing)

- The quadruped (on hands and knees) hip extension (hands directly under shoulders, lifted

thigh 90° bend and parallel to the ground, contract your abs to stabilize the spine, and place

hand on the lifted glute to make sure it contracts).

The Bridge (core and glutes)

Lie on your back with curved lower spine, feet flat on the floor and knees bent at 90º. Hands

by your side or beyond your head. In a wave, close the space off with a neutral spine,

contract your buttocks and lift your hips until knees, hips and chest are in line. Remember,

it’s not about how high you can bring your hips off the ground; it’s about how much control

you can get with your gluteus maximus alone. Try to relax your ribcage. Concentrate on not

using your hamstrings or lower back to assist this lifting action. If your hamstrings are

burning, it may be because your feet are too close to you or you’re putting too much

pressure on your toes, so move your feet further away and set your weight on your heels.

The goal is to have minimal to no hamstring activation during this movement. Make your

glutes do all the work. You may need to place your hand on your hamstrings to make sure

they stay soft. Now relax and repeat, let the lower back sway, neutralize the spine etc….

When lifting up, don’t knock your knees outwards or inwards. Complete 10 repetitions.

Focus intensely on squeezing your butt without arching your back – this is critical. You must

teach your body the difference between using your glutes and using your lower back

muscles.

Keep it honest: Make sure your glutes are squeezed at the top of the movement; do not let

your spine sag.

Make it harder: Straighten one leg up to the sky. Perform on a single leg. The straight leg is

vertical at the top of the movement. Keep the straightened leg straight and try to activate just

the glute on your grounded leg (much harder!)

Once you’ve fixed the wiring between your brain and your butt you can move on to more

advanced, functional exercises that integrate glute activation with activation of other running

muscles.

Side-lying leg lifts

Lie on your right side. Lift your left leg up to hip height. Imagine your leg weighs 100 pounds

and that you have to use your bum muscles to lift the leg up. Repeat 10 times and switch

sides.

- Forearm under head for support.

- Shoulders, pelvis and trunk stay vertical to the ground.

- Legs straight and together.

- Knees locked.

- Feet in flexed position.

- Lift leg to star position using your glutes. Hold for 10 seconds. Do not let your lifted

leg drift left or right.

- Slowly lower leg down, but do not let the leg rest on the other leg. Repeat.

Trainer’s Tip: Make sure you stretch your hip flexors, because if they are tight they can

inhibit your bum muscles from working (firing).

Hip Hike

This exercise involves recruiting the gluteals to maintain a level pelvic tilt.

Stand on one leg, bending the free-leg knee slightly so it does not drag on the floor. Stand up

with good posture, head looking forward into a mirror. Tilt the pelvis so the free side drops

down. Your stance-leg knee should not have moved nor should your head or back. Then,

focus on only the top and outside of your gluteals to pull the pelvis back until the free side is

level or even slightly higher. Slowly continue this hitching motion up and down. Complete 3

sets of 10 building up to 20 reps each side.

Single-leg Squat (is to 90º, pistol is to full depth), conf. Squatting above parallel qualifies

as shallow whilst squatting below it qualifies as deep.

- Activate your abs, pelvis stays level all the way down, the hip, knee and ankle all stay

lined up as you go down (the knee should not drag inwards).

- Focus on using the lower medial glutes (at the very lower rear of the buttocks)

- Dr. Brian Abelson, what he calls in clinical exercise today, a non-activation of the

glutes. Often in similar exercises, the knee will start tracking off to the side, instead of

straight up and down. Usually this is because the glutes are not firing correctly, so

they can’t stabilize the lower extremity.

- A great tip is to put a bit more body weight on the outside couple of bones of the foot

as you go down. This will help to keep the knee straight and aligned with the second

toe as you move up and down on it.

- Progress by at first keeping the other leg on the ground with minimal weight on it.

- 12 on each side, and 3 sets

Common mistakes

- Hip strays too far out and is not in line with the knee and ankle.

-

Knee buckles too far in (past the big toe) use your glutes to pull the knee into

alignment and keep your knee tracking in the direction of the toes

The rule of specificity

Remember that the strength, endurance, power and flexibility gained in an exercise is only transferable to exercises

that use similar loads, ranges of movement, joint angle, body position and speed of movement. This is a universally

accepted rule that no coach, trainer or physical therapist can argue with.

In simple terms it says that the strength gained in a particular exercise is only relevant to other exercises that look

and feel similar to the original exercise. For example the strength gained in doing a bench press will make you better

at push ups but wont improve your ability to throw a cricket ball, or the strength gained in doing small range squats

will help skiing but wont help you to kick a ball further.

If the body positions, loads, speed of movement and range of movement aren’t similar then the body wont transfer

the gains from one exercise to the next.

When you think about it, it makes sense, someone who is good at tennis is often good at squash but may be

hopeless at bowling a cricket ball. Someone who is good at surfing will pick up snow boarding easier than someone

who has strong legs from doing squats in the gym.

So let’s compare the two positions:

Clam/ Side lying leg lifts

Body Position..............Lying on your side

Load........................Weight of one leg

Initial Movement........Lifting leg up- contacting muscle

Speed of Movement.....Slow and controlled

Range of Movement.....from slightly lower then hip to approx 45 degrees or more

Stimulation.............Consciously driven by exerciser

Running or Walking

Body Position..............Standing on one leg

Load........................Weight of body minus the weight of the stance leg

Initial Movement........Pelvis dropping down – stretching the muscle

Speed of Movement.......Fast – less than ½ a second

Range of Movement.......From pelvis tilted 5-15 degrees up to 5-15 degrees down

Stimulation...............Unconsciously driven by reaction to gravity

Conc: Do exercises that are similar to the action of running

X) Shows that burn on untargeted muscles is NOT desired in exercises:

Dr. Kirk Iodice: “It's normal to have some burn in other muscles of the leg. However, you

should feel it primarily in the glutes. If burn in the legs is on par with the glutes, try…”

The extent of burn in muscles during an exercise is an indication of the distribution of

workload. If the burn is being felt more in untargeted muscles, then this is a good

indication that you’re not doing the exercise correctly.

We see tons of injuries to the hamstrings and lower back, but rarely encounter any sort of

injury to the glutes. The fact of the matter is that most athletes are tight in the hamstrings,

lower back and hip flexors. This collection of problems is related to a lack of strength and

motor control in the gluteal muscles. When the hip flexors (antagonists to the gluteus

maximus) are overactive, the gluteus maximus becomes weak via a mechanism known as

reciprocal inhibition. Furthermore, when our butt muscles aren’t up to the task, the

hamstrings and erector spinae muscles are forced to work overtime to compensate in the

process of synergistic dominance. This cycle often results in injury, or at the very least, suboptimal levels of performance.

Relative Glute Weakness – Quad domination (and more generally, muscles dominating

other muscles)

This

occurs

when

the

function

of

the

glutes

is

overshadowed

by

the disproportionate strength of other muscle groups, built up due to habitual movement

patterns and poor technique in training which creates strength imbalances.

Often, even in athletes who display a relatively neutral pelvic posture, the effectiveness of

their glute function is compromised due to the fact that other muscle groups (usually quads)

are, in relative terms, significantly stronger and more developed. This leads to the adoption

of movement patterns and habits which place increased emphasis on the stronger muscle

groups such as the quads, rather than allowing the glutes to contribute properly within the

motion.

This is very common in triathletes who spend a lot of time on the bike. No matter how well

your bike is set up for you, it’s always going to be a “Quad Dominant” exercise, building

strength in your thighs rather than helping your glutes also develop equally. If left unaddressed in terms of adding exercises to target the glutes, this kind of strength imbalance

can cause injury problems over time as the body learns not to use the glutes as it tries to

favour the stronger quads.

A classic example of a movement pattern that is usually influenced by strength imbalances

is the squat. Many athletes who are “Quad Dominant” in terms of strength will squat in such

a way that places excess emphasis on their quads, placing a lot of strain on the knees. This

can be observed by the knees shifting forwards over the toes and the heels beginning to lift

off the ground at the bottom of the squat.

http://www.kinetic-revolution.com/glute-inhibition-or-glute-weakness/

Strengthening the CORE for runners

The “core” isn’t just the abs. 27 muscles make up the core, the main groups are abs,

multifidus, glutes, pelvic floor muscles, erector spinæ (esp. the spinalis thoracis section) and

diaphragm.

The first few times you practice engaging your core and relaxing your legs while running,

you’ll most likely experience soreness in your abdominals the next day. This is a good sign!

By relaxing your legs, you decrease the build-up of lactic acid in those muscles, which means

little to no recovery time and you can start off every run with fresh legs.

The core is divided into two component systems:

(1) Deep stabilization system (deep muscles used more fort stabilizing the pelvis and

spine)

(2) Superficial movement system (superficial used more for moving the pelvis and spine)

Feet Three Inches Off the Floor

- Supine, feet on the floor

- Lift feet up off the floor (one at a time)

- Back no movement

Superman

- What it hits: transverse abdominals (deep abs) and the erector spinae (lower

back)

- Start facedown on the floor, with your arms and legs extended out front. Raise your

head, your left arm, and right leg about five inches off the floor. Hold for three counts,

then lower. Repeat with your right arm and left leg. Do up to 10 reps on each side.

- Keep it honest: Don't raise your shoulders too much. Keep your head straight.

- Make it harder: Lift both arms and legs at the same time.

- Squeeze your glutes in as you hold the position at the top of the movement.

- Finish with a stretch on the knees, butt close to the feet, feet plantarflexed, whole

body in one line and sloping to the ground, and arms stretched to the floor.

The Plank (IIIIIIII) strengthens the core and glutes individually

-

Keep your entire body (shoulders, back, hips and ankles in a straight line), and keep

your abs tight and pulled in.

Make it harder by rotating side-to-side (to work the obliques) or lifting one leg off the

ground (or alternate arm and leg).

For the lifted leg, slowly raise your left leg until it lines up with your back. Keep your

butt down. You don’t need to lift your legs super high. Hold this position for 4

seconds, then lower the left leg, and repeat for 4 seconds with the right leg. Repeat

both sequences three to five times.

The Bridge (IIIII) works the core too

[Progressive, 90 to 45 -> 90 to parallel] Supine/Lying Leg Raises (IIII) lying -> hanging,

lift = raise

- Lie face-up on the floor.

- Legs together, knees in a locked position and feet dorsiflexed.

- Hands on chest or behind your head. Or palms down under your glutes to take

pressure off your tailbone (and release a lot of strain on your lower back)

- Lift your chin up to keep your lower back on the floor.

- Keep your shoulders on the floor at all times to keep your chest open and not tight.

- Do not let your lower back peel off the floor. Do NOT let your lower back arch up.

(IIIIII)

- Lift your legs as far as they can go (vertical at best), keeping them straight.

- Hold for 10 seconds.

- Keep your feet flexed to engage your glutes into stabilizing your hold.

- Bring your legs down only as far as your lower back stays on the ground. If you bring

your feet parallel to the ground, and your lower back is off the ground, then you are

not doing the exercise correctly and you are not ready to bring them down that far.

(Your core is not strong enough to hold the leg by itself)

- Lower your chin and repeat, starting with lifting your chin.

- "Make sure your lower back doesn't arch off the bench” Shelby Young, ACSM

certified Athletic Performance Specialist; Hampshire Hills Sports and Fitness Club;

Milford, NH

- Practitioners exercise caution to keep the lower back in contact with the floor and

place hands to sides or under lower back for support. If the back stays flat on floor

and abdominals are tight, this keeps the abs engaged. Otherwise it would just be a

hip flexor movement.

- Bad for your back if you are not strong enough to be doing it. Any exercise where

your full leg is cantilevered out has the potential of straining your back if you cannot

properly position your pelvis. Really work on your hollow position. Hollow rocks, Nups, V-ups etc. On this exercise if you can not keep your lower back on the floor with

your hips tucked under you need to strengthen your abs more before really working

them hard.

Easy way to self-check back position during leg raises:

1) Lay down on your back with your legs in the traditional 'sit-up' position (feet planted and

knees bent).

2) Take your index finger of one hand and slide it under the small of your back.

3) Try to eliminate any space between your back and the mat by 'crushing' your finger.

Remember this feeling.

4) Now start on your back, but with your legs straight up (toes pointing to the ceiling) or as

close as you can get. Find the small of your back with your finger. Crush it.

5) Lower your legs slowly. If you can't crush your finger, you've gone past your effective

strength range. Don't be surprised if you don't make it very far. Back up and work the range

you can hold correctly (holds are great for this) until you get stronger. Work to being able to

go 'all the way'.

Once you have an idea of where your strength range is, you don't have to keep using the

finger - you will know when you reach your limit.

NOTE: DO NOT put your hand under your butt/back like you see people do all the time. This

takes the majority of the work away from the abdominals and will do nothing to help you learn

the movement. Most people you see in gyms perform leg lifts terribly wrong. Don't do what

they do!!!

Metronome (obliques)

- What it hits: obliques

- Lie face-up on the floor with your knees bent and raised over your hips, with your

ankles parallel to the ground, your feet lifted, and your arms extended outward.

Rotate your legs to the left side, bringing your knees as close to the floor as possible

without touching. Return to the center, then move your knees to the right side. Do

10 to 12 reps on each side.

- Keep it honest: Make sure not to swing your hips or use momentum; start the

movement from your core and continue to move slowly from side to side.

- Make it harder: Keep your legs straight.

Side Bends (number one for obliques)

- Bending your side to pull a weight up the side of your leg.

Ab exercises ranked by EMG activity: http://suppversity.blogspot.com.au/2011/07/suppversity-emgseries-rectus-abdominis.html

Be aware

Just like many trainees fail to actually flex their abs and thus train their psoas major instead of

their abs in hanging leg raises, a similar shift away from the m. rectus abdominis and towards

psoas occurs in all ab exercises where your legs are held in a fixed position, the most

dreaded example being the classic sit-up, from which generations of trainees developed a

hollow back (hyperlordosis).

kegel for pelvic floor muscles

Strengthening the HAMSTRINGS for runners

Eccentric Leg Slide

- Paper plate under heels.

- Start in the bridge position (body, hips and knees aligned)

- Biceps and elbow on the floor.

- Slowly lower your legs into lying position.

- Do not let your hips sag below the line, keep them up.

- The athlete must hold a glute contraction in order to keep the back from slumping.

- Heels sliding along the floor.

- At the end of the movement (when the sliding leg is at full extension), come back into

the bridge position. Your butt never touches the floor.

- A wrapped up towel or a board to make sliding a bit easier (esp. coming back up)

- Make it harder: Do on single-leg.

Standing Superman

- Use a wall as balance. Stand on one leg and extend your opposite leg out behind

you. Keep this leg straight and lift it off the ground.

- Arms reaching out.

- Both legs are straight.

- Bend at your hips until your arms, torso and lifted leg are all horizontal.

- Finish the movement with the lifted leg in high knee position. All repeated in

continuous motion to apply burn to the hamstrings.

- The leg stays lifted throughout the exercise.

- Aim for 15 to 20 of these leg lifts and switch sides. Repeat for 3 sets.

Hamstring Push-up

- Feet elevated on a Swiss ball or a chair that is up against a wall

- Knees bent at about a 90º angle.

- Move into bridge position, dip close to the floor, then back into bridge position.

High Bench Step-Up

-

Stand in an upright position; body, hips and knees aligned.

Use the second step. Chair brings thigh above the hips, which isn’t good for the knee.

One leg at 90º angle, shin vertical (foot on the bench entirely)

Straight back

Pull your knee closer to your body or pull your body closer to your knee to activate

your hammies.

Pull your standing leg closer to the step (but not too close) to activate your muscles

more.

Rear leg on tippy-toe to remind yourself not to push off with that leg.

Push your body down on your hamstring and press down on your heel.

To help balance, pump your arms like in the running motion.

Squeeze your glutes as you come up.

Kick your butt with your heel on the way up. Holds straight alignment.

End with your lifted leg in high knee position (w/ tucked in thigh).

Single Leg Push-off (Plyo)

- Keep the front leg straight as you jump off the leg.

- Rear leg in high knee position.

- Gain as much height as possible.

- Land mid-foot.

Plate Drag

- Take socks off (makes it too slippery), shoes or barefoot

- Heavy weight (11, 15 or 20 kilograms) on floor (not any slippery surfaces).

- Experiment with increasing friction under the weight.

- Legs fully extended, heel on plate.

- While keeping your body stable, slide the plate towards you by contracting the

hamstring muscles of the working leg. The opposite leg stays extended.

- Furthermore, since it doesn't have an eccentric (negative) portion, this exercise will

lead to little micro-trauma and thus little, if any, soreness. For that last reason it's a

favorite of several track athletes since running on sore hams is brutal and dangerous.

“Natural”/Floor Glute Ham Raise (GHRs)

- ‘Natural’ because the GHR machine is very expensive and unnecessary.

- You can lock calf, ankle or heel under a heavy object/railing (barbell, bed, etc).

Board, 8 paper stacks and 2 heavy books.

- If you lock your calf or ankle, protect them with towels wrapped around the area or

around the railing.

- If you lock your heel, the heel must be dorsiflexed, NOT plantarflexed, and bear in

mind that heel is not as fixed as calf/ankle.

- Ankle-knee joint is parallel to the ground.

- Must place a pad or layers of towels (pillows bounce, clothes are unlevel) under your

knees to protect them.

- Stick towels to the metal railing to reduce stress on the calf/ankle.

- Arms should move like in a push-up, hands directly below shoulders.

- Never break (bend) at the hips, not even on the way up.

- Tuck your chin in.

- Before initiating the movement, think about actively squeezing the glutes and getting

the core tight. You want to get the pelvis as close to neutral as possible, and

minimize any excessive arching of the lower back.

- Keep your hips and abs tight as you go down.

Common Mistakes

- Back hyper-extends to substitute for a lack of glute and ham strength. If glutes and

hams cannot pull your body up, then your back will try to perform the work.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWcj7WcLFSI

“I do my glute ham raises on the floor, stick my feet under a rail and away I go. Hurts like hell if my knee cap moves

though.”

“Yeah, that's the exact reason why I won't ever do them like that, you need to have your knee elevated.”

For basic eccentric hamstring exercises

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QXAgNofkgkY

On the ineffectiveness of the hamstring machine:

“Because a leg hamstring machine curl will only build the hamstring right under the knee and nowhere in your

buttocks or throughout your thigh, the machine hamstring curls are indeed a waste of time”

Quad dominance

4:3, 60-80%, 75%,

Exercise physiologists recommend a strength ratio between quadriceps and hamstrings to be

around 3:2. That is, your quadriceps should be about 1 1/2 times stronger than your

hamstrings. In other words, develop your hamstrings but don’t overdo it.

All hamstring exercises will benefit runners but recent research shows that eccentric hamstring exercises such as the

eccentric leg slide are best at helping to prevent quad dominance from occurring.

"Eccentric exercises strengthen the connective tissue too, instead of just the muscle."

“If you want to protect your hamstrings, you have to get your glutes to contribute because, what’s going on here is

that most hamstring strains come from the hamstrings working when the glutes quit. If your glutes were involved and

doing the job that they were supposed to do, your hamstrings would only be doing the job that they’re supposed to

do, instead of trying to do the job of both muscles. So we want to be able to fire the glutes at all times.”

Twice a week for individuals with no hamstring trouble and 3+ times a week for those with (as part of maintaining a

particular level of fitness and injury prevention).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnBc_jp5QC8

http://www.projectswole.com/weight-training/the-top-5-best-hamstring-exercises/

drag

including

the

plate

Strengthening the HIP MUSCULATURE for runners

Takeaway is that if the hip abductors (the muscles that move the lower leg sideways away

from the body) and the hip flexors (muscles that move the lower leg in toward the body) are

weak, the knee doesn't track as well as it should. Hip adductors move the lower leg

sideways towards the midline of the body.

There are four groups of hip muscles: the gluteal group, the adductor group, the iliopsoas

group (standing for the iliacus + psoas), and the lateral rotator group. While it is important to

note that many of the hip muscles are responsible for more than one type of movement in

the hip, the psoas (major) is the primary hip flexor, assisted by the iliacus, the gluteus

maximus is the main hip extensor, the adductor group is the main hip adductor, the gluteus

medius and minimus are the main hip abductors and medial rotators (of the thigh), and the

lateral rotator group and gluteus maximus are the main lateral rotators.

The hamstrings are the second most important hip extensor, after the gluteus maximus. The

rectus femoris (of the quadricep) is the third most important hip flexor, after the psoas and

the iliacus.

Roles in the hip musculature

Movement

Lateral

rotation

Medial

rotation

Extension

Flexion

Abduction

Adduction

Muscles (In order of

importance)

• Sartorius • Gluteus maximus

• Quadratus femoris

• Obturator internus

• Gluteus

medius and minimus

• Iliopsoas

(with psoas major)

• Obturator externus

• All

functional adductors

except gracilis* and pectineus

• Piriformis

• Gluteus medius and

minimus (anterior fibers)

• Tensor fascia latae*

• Adductor

magnus

(long medial fibers)

• Pectineus (with leg abducted)

• Gluteus maximus

• Gluteus medius and

minimus (dorsal fibers)

• Adductor

magnus

• Piriformis

• Semimembranosus*

• Semitendinousus*

• Biceps

femoris*

(long head)

• Iliopsoas

(with psoas major)

• Tensor fascia latae*

• Pectineus

• Adductor longus

•

Adductor brevis

• Gracilis*

• Rectus femoris*

• Sartorius*

• Gluteus medius

• Tensor fascia latae*

• Gluteus maximus

(fibers to fascia lata)

•

Gluteus minimus

• Piriformis

• Obturator internus

• Adductor magnus

(with adductor minimus)

• Adductor longus

• Adductor brevis

•

Gluteus maximus (fibers

to gluteal tuberosity)

• Gracilis

• Pectineus

• Quadratus

femoris

• Obturator externus

Hip flexors. Located in the front of the thigh. Muscles in the hip that act to move your thigh

closer to your body. “The psoas and the iliacus are the only hip flexors capable of bringing

the hip above 90 degrees”. Besides hip flexion, hip flexors also affect the tilt of the pelvis

where tight flexors tend to cause anterior pelvic tilt and weak flexors cause posterior tilt. The

tensor fascia latae (TFL) is a synergist in hip flexion that often tends to be tight in individuals

with tightness in the other hip flexors.

“Note on Terminology: ‘Hip Flexors’ versus ‘Muscles that flex the hip’

Although there are several additional muscles that “flex the hip” (sartorius, adductor complex,

anterior fibers of gluteus minimus), when human movement professionals use the term “hip

flexors” they are generally referring to the “Big 3″:

- Psoas (Iliopsoas)

- TFL

- Rectus Femoris

These muscles play the largest role in hip flexion and of the muscles that flex the hip are most

prone to adaptive shortening and over-activity.”

Weak hip muscles allow the legs to angle inward or outward instead of keeping each stride in

line.

Straight back in a chair, not slumping or hyper-extending (overarching the back).

Use your hands and lift the leg up to as far as the hip can bend, then hold for 10 seconds,

then slowly lower the leg. For more resistance, press your arms down on the top of your thigh

as you hold the flexed leg.

Two groups of hip flexors; (in the standing position) the iliopsoas is operative when we flex

our hip above 90º and during movement of the lower spine. The second group brings the hip

from 0º (standing position) to 90º.

We do not want to flatten or change the contouring of the lumbar spine. We want to maintain

the natural inward curvature.

Hip flexor lunge stretch -> high knee position (plyo)

- Start in the hip flexor lunge stretch.

- Stretch hip flexor out then fire, bringing the knee up as high as possible.

Scissor/flutter kicks

- All forms of leg raises, squats

One leg bent on high bench at 90º. Repeat quick pulses above 90º, until fatigued.

Find the best exercise/s for the hip muscles

One of the best websites giving a list of strengthening exercises for a lot of muscles

http://www.exrx.net/Lists/Directory.html

High knees, working only the top part of the thigh, pulling the knee up, not too far outwards.

Video Powerpoint

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LVIkfuhexqc

Why you shouldn’t be doing certain exercises if your abs are not strong. (putting too much

stress on hip flexors usually causes anterior tilt and lower back pain)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATC9d-iYeAw

High-knee run (as a warm-up? when other exercises are just as similar in action…)

Leg raises (and hanging knee raise as harder version)

“If you have an exercise band, you have a workout partner”.

Hip extensors. The primary hip extensors are the gluteus maximus and the three hamstring

muscles (long head of biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus). This can

confuse people because the gluteus maximus is often lengthened and inhibited due to

shortening of the hip flexors, while the hamstrings are often shortened and tight [because

they have taken over the work of the gluteus maximus – synergistic dominance].

It’s often easier to think in movements rather than muscle groups. If one extensor muscle

group is weak (such as the gluteus maximus), the others (such as the hamstrings and erector

spinae) will be forced to compensate.

Hip abduction is working the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus in an abducted

movement. So, train hip extensors, flexors and adductors in the movements of extension,

flexion and adduction. Remember not to simply strengthen them, but strengthen them in the

movement required to keep the knee tracking correctly.

“Poor hip abductors can cause overpronation”. This shows that you need to train even

the small muscles in activation and isometrics.

“The three hip abductors are the TFL, gluteus minimus, and gluteus medius. More often than

not, you'll find people with a tight TFL and dormant gluteus medius and minimus on both

sides. One of our goals in this series is to work to correct this unfortunate trend.”

If you examined a large number of strength athletes, you'd probably notice two issues that are

the most prevalent:

1) Tight/overactive hip flexors, ITB, biceps femoris, adductors and piriformis.

2) Weakened/inhibited hip extensors (specifically the gluteus maximus), gluteus medius

and minimus, and possibly medial hamstrings.

To address both of these issues, you need a routine that not only lengthens and inhibits the

tight/overactive muscles, but also recruits and "fires up" the under-active muscles. Don’t focus

too much on working Muscle X or Y; focus more on the movements and the muscles will take

care of themselves.

Stand up, lift your leg to the side, keeping the leg straight and muscles flexed, and slowly

lower the leg back down (standing hip abduction)

The same thing, but lying down, called side-lying hip abduction.

Strengthening the ‘KNEE’ joint for runners

The assumption that “the problem originated right where it manifests: at the knee” is very

flawed. As you can see, the muscle that becomes injured is rarely the problem, but usually

the victim. The painful area is often not the area at fault. Pain will be felt where the body

breaks down due to too much stress. It is important therefore to recognize and address the

causative factors and not just focus solely on relieving pain at its location. Yes, the quads

control the movement of the patella (kneecap). They are the primary extensor of the knee.

Yes, the hammies flex and rotate the knee. They protect the collateral and cruciate

ligaments as the knee rotates. Yes, the popliteus (a muscle behind the knee joint itself)

helps rotate and stabilise the knee. And yes, the calf muscles that attach above and below

the knee mainly control ankle movement (dorsiflexion and plantarflexion), not knee

movement. But the integrity of the knee depends on the alignment and strength of your

entire leg from your hip joints to your feet. Strong hip muscles such as hip adductors and

abductors keep the hip joint stable. If the hips are weak or out of alignment, more pressure

is transferred to the knees. Strong ankles protect the knee from unnecessary stress if the

ankles were not strong. Tightness in the IT band and anterior hip muscle (TFL) dominance

over the posterior hip muscles (glutes) can cause ITBS (pain on the outside of the knee).

There’s a much bigger (and more significant) picture than just vastus medialis. It’s more

complex than simply where the anatomy originates.

Even when referring to pronation of the feet, overpronation is a symptom occurring at the

foot, not the cause (improper footwear, poor running form/posture, tight muscles, etc.)

“A sports podiatrist will often work closely with a physiotherapist as many leg and foot

problems are secondary to problems in the lower back and pelvis.”

Wiki says: “Medical and other allied health practitioners often suggest improving the strength and/or

activation of the vastus medialis as a strategy in the treatment of patello-femoral pain syndrome -

sometimes called runner's knee. The biomechanical cause of patellofemoral pain syndrome is

unknown however and may have more to do with weakness of extensors of the hip (i.e. gluteus

maximus)”.

For most people, the neurological connection to this muscle [the vastus medialis] is weak.

Lateral or medial tracking of the knee is caused by thigh muscle imbalances (in strength and

in tightness). If, for example, the VMO is too weak, then it can’t keep the kneecap aligned

properly as you bend your knee each stride. The medial pull of the VMO is overwhelmed,

either by the tightness in the IT band or the lateral pull of the vastus lateralis and IT band.

Repetitive compressive or shearing forces (e.g. jumping) on the PF joint can cause knee

issues.

Imbalances (in weakness and tightness) of the thigh. Muscles/tendons on the outer thigh

include the outer quad muscle (the vastus lateralis), the TFL, the IT band, and the hip

abductors. Muscles/tendons on the inner thigh include the inner quad muscle (the vastus

medialis), and the hip adductors. Fixing these imbalances

Strengthening the Vastus Medialis Obliquus (more obliquely aligned than the rest of

the vastus medialis)

Anything that holds or squeezes the inside of the thigh will strengthen the VMO.

With (or without) patellafemoral pain, the best way to rehab your knee is to strengthen

the VMO through general quadriceps exercises. (IIII

Strong hip muscles = good knee.

Also poor posture (pelvic tilts and poorly distributing weight) causes bad knee.

Do not try to isolate it, train the quads together (though inner vs. outer should be trained).

Understand the muscles involved in stabilizing the knee joint

ITBS is (intrinsically) caused by tight IT band, weak hip abductors, poor control/weakness of

knee muscles, esp. the quads, myofascial restrictions in the thigh and hips, which increases

tension on the band, dominance of anterior hip muscles over posterior hip muscles,

excessively flat feet, etc. So, strengthen the IT band (a tendon along the side of the thigh) by

strengthening hip abductors and knee muscles, making the band more flexible, etc.

Remember: you don’t necessarily have to target that exact muscle, instead look at the

muscles that work with (on either end of the tendon)/against (on the medial side of the thigh)

it, as well as other muscles in the posterior chain that aren’t actually directly connected to the

knee (the hip musculature).

Vastus medialis and the IT band

The number 1 myth surrounding ITBS is that it causes hip and thigh pain. It does not. ITBS is

a knee pain condition only. Secondly, ITBS is truly a side of the knee condition.

The vastus medialis (the teardrop muscle) is often underdeveloped. This can cause the

patella (knee cap) to track laterally toward the outside of the leg. [Not medially?????

Regardless, it is undisputed that a weak VMO will cause the kneecap to track sideways

(laterally and medially)]

Wiki says: “Often medical and other allied health practitioners suggest improving the strength and/or

activation of the vastus medialis as a strategy in the treatment of patello-femoral pain syndrome sometimes called runner's knee. The biomechanical cause of patellofemoral pain syndrome is unknown

however and may have more to do with weakness of extensors of the hip (i.e. gluteus maximus)”.

Shows you should ready yourself to tackle all common injuries in sport and in running.

Quad/hamstring/glute squeezes: Sit tall in a chair with your fingers placed on the inside of

your knees. Simultaneously squeeze your bum, the back and front of your upper legs and the

VMO muscles under your fingers. Do at least 10 reps once per day. Don't be discouraged if it

takes you a couple of weeks to feel the VMO fire. For most people, the neurological

connection to this muscle is weak.

Open

http://www.caaws.ca/girlsatplay/stuff/health/knees_hurt.htm

Strengthening the CALVES for runners

Standing Calf/Heel Raises

- On a step or edge of treadmill, stand on the balls of your feet, hip-distance apart.

- Keep your pelvis back.

- Brace your abs so that you rise up, not forwards or backwards.

- Maintain control at all times.

- Slowly lift up as high as you can, then lower yourself down until your heels are just

below the step.

- Do not change the angle of your knees throughout the movement.

- Don’t mess with pointing toes in or out. Parallel feet activate both the inner and outer

part of the gastrocnemius.

- By far the most common mistake is turning the calf exercise into a toe exercise by not

pushing from the balls of your feet, but from the toes.

- Position your heels farther off the edge, but not too far out (you still need the ball of

your foot to be on the step).

- Repeat 10-15 times per leg.

Seated Calf Raise

- Heels directly under knees.

- Heavy weight on thighs.

- Keep the balls of your feet on the ground.

- Make sure you don’t roll your ankles out, keep your weight in line with the first and

second toes.

- Do not actively bend the knees during the movement.

Soleus vs. Gastrocnemius activity

- It is worth mentioning that the overall activation of the calves is maximized during

standing and bent-over (donkey) calf raises, while the m. soleus activity is highest

when you do seated calf raises.

- A rule of thumb with regards to the activation of m. gastrocnemius vs. m. soleus is

"maximize (i.e. larger) knee angle (as in standing calf raises or donkey calf

raises) to maximize gastrocnemius, minimize (i.e. smaller) knee angle (as in

seated calf raises) to maximize soleus activity". Note: It is nonetheless imperative

(especially if you are using higher loads) not to forcefully lockout your knees, in order

to avoid injury.

“I really exaggerate the motion, at the top a peak contraction, and at the bottom, a good

stretch [for the full range of motion]. Not what you see in the gym so often - short, choppy

movements.”

Cardio Circuit

Exercise

Walking on toes, with hand weights.

Small double-leg hops on toes, with weights. <- very similar to jump rope

Skipping/doing hills

Sit to stand calf raise (with physio ball), 90º position (weights held on top of each knee), raise

calves, then in raised calf position, raise back till legs are straight, squeeze the calves at the

top to get the last bits of fibres out (The peak contraction principle is used at the completion of

a rep in which you hold and squeeze the contracted muscle momentarily before returning to

the starting position).

Gastrocnemius: This is the meat of the calf muscles. If you notice it is split into two heads.

Much like the bicep muscles. The main exercises for this are standing calf raises, donkey calf

raises and calf raises on the leg presses. As I mentioned before it is extremely vital to get a

peak contraction in each rep! This is the only way you are going to create that peaked and

fully conditioned look in your calves.

Soleus: This is the lower part of the calf. Working this will help to widen your calves and

create separation up the middle, almost splitting the gastocnemius into its diamond shape.

The main exercise which emphasizes this is the all powerful seated calf raise.

Tibialis anterior: It’s funny because you rarely see people working this muscle. Yet it is half

way responsible for making your calves look absolutely massive from the front! The main

exercise for this is reverse calf raises. Believe me when you see the gains you get from this

exercise you will learn to love them. However there is a special and unorthodox method I will

explain that is essential to this exercise! [Partial (1/2 or 1/4) reps after failure and strip sets

(strip weights off during failure period till all weights are off)].

Toe raises and calf raises (opposites of each other, toe raises stand on the heel and lift the

toes, calf raises stand on the toes and lift the heel).

Calf/heel raise (not on the ground). Then single-leg. (note, controlling the drop of the calf

(eccentric) is just as important as raising the calf).

Not doing it on the ground will promote not leaning forward into the movement, and keep your

pelvis back.

Bent-knee calf raise focuses on soleus.

Donkey calf raise (both legs or single leg) 90 degrees bent – needs a weight on the back, like

on a donkey

Seated calf raise (activates the soleus more than the gastroc since knees are bent). (also no

bouncing!).

Jump roping is basically jumping, and therefore jumping trains the calves.

The natural tendency when doing calf raises is to roll outward onto the other four toes, turning

your ankle as you do the movement. But when you do calf raises like this you can't totally

peak the calf muscle, which means you end up losing training intensity. It is very important

that the pressure of the movement is directly on your big toe.

Remember! When doing calf raises, keep the lower leg moving straight up, not left or right.

(Do not roll the ankle out!)

Note: the soleus makes up 60% of the calf. However, you also have to ask yourself how

much it is used in running compared to gastroc.

http://www.momentumsports.co.uk/TtCLegs.asp

http://suppversity.blogspot.com.au/2011/08/suppversity-emg-series-gluteaus-maximus.html

Strengthening the two main tibial synergistic muscles for runners: tib ant and tib post

Resistance Band

Wall Shin Raises

- Buttocks, back and shoulders to the wall.

- Heels a foot away from the wall.

-

Sink your feet back so that they almost touch the ground, but not rest on it, which

would give your tib ant too much of a rest between flexions.

Along with the basic raise, pulse (short and quick movements over a very small range

of motion) at the top of the movement.

Change to single leg.

Not really however a running-specific exercise.

Reverse Calf Raises

- Stand with heels on a step.

- Pull feet up towards body as far as possible.

- Hold a peak contraction (1 second) at the top of the movement.

- Return by extending feet until toes are pointing downwards. This means keeping the

body still as you lower.

- Lower your feet slowly. It should take about 2 seconds to lower your feet to the

bottom of the movement.

- Keep knees and hips straight.

- Position heels closer to the edge of the platform or use one foot.

Dorsiflexion exercises for the TA

Perform dorsiflexion exercises for your anterior tibialis using an ankle weight. Place the

weight around the foot, just underneath your toes. Pull your toes in toward you 12 to 15 times.

Repeat this exercise for two to three sets.

Single-leg toe raises on the step (better than on the ground) as with calf raises

Tibialis posterior works similarly to the calves in terms of plantarflexion.

toe raises, toe curls

The term shin splints is a common misnomer in sports medicine.

The National Academy of Sports Medicine

One of the muscles you would want to strengthen is the anterior tibialis. This muscle runs

down the front of your lower leg and helps control your foot while running or walking. You can

apply resistance to the top of your foot via tubing or a cable and then pull your foot back

toward you against the resistance. This strengthening exercise, called resisted dorsiflexion,

will target the anterior tibialis muscle. A second muscle to strengthen is the posterior tibialis.

This muscle runs deep down the back of the lower leg and also helps control the foot.

Perform single-leg calf raises with your foot slightly turned in toward the center of your body

to help strengthen this muscle and also decrease stress to the lower leg when running.

Perform 1-3 sets of 10 - 15 repetitions of each exercise.

1. Wall shin raises

a. Stand with your back to a wall, with your heels about foot-length from the wall. Then, lean

back until your buttocks and shoulders are resting against the wall;

b. Dorsiflex both ankles

simultaneously while your heels remain in contact with the ground: bring your toes as close to

your shins as you can, then lower your feet back towards the ground, but do not allow your

forefeet to actually contact the ground before beginning the next repeat;

c. Maintaining

your basic position with your back against the wall, dorsiflex your ankles to almost their fullest

extent, then quickly dorsiflex and plantarflex your ankles 15 times over a very small range of

motion. These short, quick ankle movements are called pulses. Then, progress to the singleleg wall shin raise:

f. Start in the same position as before, but with only one foot in contact

with the ground, while the other rests lightly on the wall behind you. Now your full body weight

is on one foot - as it is during running.

There's no need to rest between sets; simply carry out

15 reps plus pulses on one foot, shift over to the other foot, and so on until you have

completed three sets with each foot.

Although wall shin raises are a great routine for the shins, they are not quite as runningspecific as the exercises which follow.

2. Heel step-downs

Simple but devastatingly effective exercises for preventing MTSS. Take a normal step

forward as with walking. Then take dramatically larger steps. Then step down from a high

step. Sole does not touch the ground. Once you are an accomplished wall-shin-raiser and

heel-step-downer, move on to the next two exercises, which are the ultimate MTSS

preventers.

3. Heel hops

a. Using erect but relaxed posture, standing on your right foot, with your right knee just

slightly flexed and your left knee flexed to about 90¡ so that the foot is completely off the

ground;

b. Hop forwards on your right foot, but instead of landing in the mid-foot area, land

on your right heel and hold the position for about two seconds, keeping the rest of your foot

off the ground;

c. Repeat on the same foot 14 times more, then repeat on the other foot.

Initially, the hops should be just 4-6 inches in length, but you can increase the hopping

distance as your strength and coordination improve. Another key progression is to gradually

build up your speed of heel hopping, so that you are moving forwards quite quickly, while

remaining on your heels. You can gradually move up to 3 x 15 hops per leg (or even more),

but the ultimate progression is to carry out the exercise on a slight downward slope (initially

just 1-2%). Using the slope will put severe pressure on your shin muscles, so be careful to

begin with a modest number of reps.

Don’t advise heel running, it doesn’t seem natural or good for you.

Resistance band on foot adduction

We'll show you what to do

In an investigation carried out at the Centinela Hospital Biomechanics Laboratory in

lnglewood, California, 15 competitive and recreational runners ran at different speeds while

their lower leg muscles were hooked up to a device which measured muscle activity. Five

important muscles were studied, including three calf muscles (the gastroenemius, soleus, and

tibialis posterior), one shin muscle (the tibialis anterior), and a unique muscle---the peroneus

brevis-which runs down the lateral side of the lower leg to the outside of the foot.

Three important facts emerged from the Centinela study:

• The calf muscles contract most powerfully during the "stance phase" of running when the

feet are in contact with the ground. Contrary to popular belief, the three calf muscles

do not provide much power for push off but instead prevent the ankle joint from

collapsing forward when the foot hits the ground.

• Although the calf muscles are busy while the feet are on the ground, they're pretty lethargic

during the rest of the gait cycle when the feet are off the ground, moving backwards

or forwards. In fact, the most active lower leg muscle is actually the tibialis anterior, a

strip of sinew which runs down the shin to the inside edge of the foot and pulls the

foot inward and upward. During running, the tibialis anterior contracts forcefully about

twice as often as any of the other four muscles, so it is probably the muscle most

prone to fatigue. As it becomes tired, the risk of shin splints and stress fractures is

likely to rise, as does the amount of pronation occurring at the ankle joint (excessive

pronation has been linked to a variety of running problems, including knee injuries).

Thus, it is critical for athletes to make their tibialis anterior muscles as strong and

fatigue proof as possible.

• The peroneus brevis muscle contracts fairly lazily during medium and slow speed running

but dramatically increases its activity at race speeds. Strengthening the peroneus

brevis should improve foot speed and stabilize the ankle during high velocity running,

lowering the risk of injury.

Learn the pistol squat on the stairs, it’s much easier that way.

Exhale upward movement, inhale downward movement

“sshhhhhh” is the sound of athletes emphasizing exhaling.

Pushups work the pecs (the agonist muscle)

If they brace their lower back and keep a straight line from their shoulders to knees, the core

musculature has to work very hard to prevent the low back from extending.

a relaxed ankle

How do you change your position and motion?

“Simply it takes practice. Practice sensing and adjusting your position, your effort, tension levels, and

balance. A key skill here is body sensing, and a key concept is gradual progress. Just pick one or two

focus points at a time and practise them. With consistent practice, you can create new habits.”

Avoid training upper body and cardio on calf training days. ?

Remember: the majority of running injuries are overuse.

rotational squat

Arms rising to the sky for overhead squat, making sure the core works by itself.

Quad-dominant workouts would include anything that forces you to move more from your

knee than from your hip.

Flexibility to be in a different booklet.

http://saveyourself.ca/tutorials/iliotibial-band-syndrome.php#sec_what_tissue

a knee muscle is a muscle that moves/controls the knee.

Balance is with strengthening muscles that are weak in balance.

Balance (and improving proprioception)

Reverse lunge with rear leg raise

Agility dots

Single leg ventral (back and forwards) and lateral hops

Plank extensions (levels 1-5)

Doing all previous exercises on one leg.

You should never lock out the knee during exercise, because otherwise you’re just relying on

the bony congruency of the knee joint. Whenever jumping, do not land on locked knees. Keep

a slight bend in them as you land.

http://www.fitnessblender.com/v/exercise-detail/Single-Leg-Lateral-Hops/66/

Make the exercise dynamic only after you’re able to do the static exercise easily.

Dumbbell lunges, switching between left leg and right leg lunge, jumping and scissor kicking

in between. Bend the leg after you scissor-kick, don’t keep the leg straight. Parallel scissorkick to keep the feet aligned, keep the body straight throughout the movement. Make sure

everything else is kept straight (foot, knee, pelvis).

Strong abs improve balance.

Athletic Vid

Front Scale (Standing Superman), 10 secs – trying to hold a T-position.

Side Scale

Back Scale (remember: slowly go back)

Relevé - 10 secs

Single leg, quarter turn (or crow hops), 5-10

Quarter turns, in (medial side of standing leg) and out (lateral side of standing leg) - 5 in, 5 out

Half turn, in and out, 3 – shooting for 180°

360° ultimately

Balance Exercises for runner’s world

http://www.runnersworld.com/article/0,7120,s6-238-263--9588-F,00.html

You just can’t isolate a single muscle in a functional exercise. It’s unnatural.

Weakness tests

- single-leg squat (control) for core stability

- clam (bent knee) and hip abduction (straight knee) for two parts of the glutes

Pancake Butt

http://www.fixyourrun.com/2012/04/pancake-butt/

http://www.fixyourrun.com/2012/04/fixing-your-pancakey-butt/

Factors such as excessive sitting during daily life can result in the Hip Flexors becoming

chronically tight and over-active, pulling the pelvis into a anteriorly tilted position. This overactivity of the Hip Flexors, in particular Iliopsoas can result in a neuromuscular issue following

reciprocal inhibition, where one muscle group (in this case the Glutes) is inhibited by the

excessive activation of their antagonistic muscle group (in this case the Hip Flexors).

Low-down butt

Muscles out of balance: hip flexors and glutes

The problem: Your hip flexors are overcompensating, so your buttock muscles aren't working

when they should. The upper hip muscles (gluteus medius) also aren't activating effectively,

either because they are weak or because your inner thighs (adductors) are strong and rotate

your legs inward.

Hamstring dominance (inactive glutes and tight hip flexors)

1,2,3,4,5 steps – inhibit, lengthen, activate, integrate, reinforce

(you have to be able to breathe in isolation, AND breathe during functional exercises) –

therefore both strengthening and activation docs

Breathing whilst contracting the core (specifically the diaphragm)

It is possible to keep "activation" with the breath in but THAT is a matter of practice and

coordination.

So generally during my inhalation phase of my breath my core shouldn't be too ''activated''?

Only during the exhale phase should my core be ''activated''? So, it's basically an on/off

thingy synchronization with my breath?

Practice "that much" for now. You cannot practice the entire technique at once. It takes years

to go deeper. But with each level deeper, greater benefit.

Make sure your shoulders are relaxed and concentrate on breathing into the sides of your

ribcage to take emphasis off the diaphragm - try not to breath into your abdomen and not into

your upper chest. Remember to breathe normally throughout all the exercises - it is common

for beginners to hold their breath as they focus on contracting the core.

To breathe during any type of abdominal exercise, breathe in while you are in the resting

position. Exhale forcefully as you flex or rotate your upper torso. The fuller the exhalation, the

deeper the abdominal contraction. Inhale as you return from the movement.

You don’t change the way you breathe just to keep your core muscles turned on (not talking

about exercising the abs).

Proper breathing is simply done by exhaling during the contraction of a muscle through its full

range of motion and slowing down the movement or exercise to coincide with the natural flow

of breath. A good starting point is 3 seconds to contract and exhale then 2 seconds to retract

and inhale. Depending on your level of fitness and size of lungs you may need to adjust the

seconds. Just remember to keep the breath moving in then out in a continuous rhythmic

fashion. Avoid holding your breath or performing the valsalva maneuver which is the action of

contracting your muscles while holding your breath creating unnatural pressure internally.

{Breathing is related to the strengthening exercises}

Feeling the difference between releasing the muscles and contracting the muscles. You have

to educate yourself on what you are supposed to be feeling.

Unnecessary contractions

Contracting muscles that are not necessary to the movement being performed inhibits your

body’s ability to move freely.

Working the Transverse abs

Pelvic tilts

Crunchless crunches - vacuum exercise

Supine scissor kicks

Abdominals

http://weighttraining.about.com/od/techniquesandstrategies/a/abs_exercises.htm

Progressing with the vacuum

http://www.realjock.com/workout/1096/

Relationship of PF and TA (co-fire together)

Relationship of TA and RA (bread loaf vs. vacuum)

{How to perform exercises in posture is definitely strengthening doc}

Neutral spine

Check that your joints are in a neutral position. It doesn’t mean that you have to be scared

and only stay in neutral. Of course you’re allowed to go into flat or curved back. What is

does mean is that for the majority of the time that you are dealing with gravity, stay in

neutral. Think of it as your home base.

Stretching tight, overactive muscles is ‘inhibiting’ them.

http://www.beginnertriathlete.com/cms/article-detail.asp?articleid=486

http://www.physioadvisor.com.au/8118650/hip-strengthening-exercises-hip-rehabilitatione.htm

http://running.competitor.com/2011/04/news/the-3-best-core-exercises-for-runners_26101

http://running.competitor.com/2012/03/training/running-101-how-often-should-yourun_12188/4

http://running.competitor.com/2012/06/injuries/the-10-commandments-of-injuryprevention_1417

Most common problems in sport

http://www.sportsfocusphysio.com.au/CommonProblems.html

Top 3 solutions to a range of the most common running injuries

http://runningphysio.wordpress.com/2012/06/21/top-3-solutions-for-common-running-injuries/

Lolo Jones’ core workout Runner’s World