Playing the Market (Approach)

advertisement

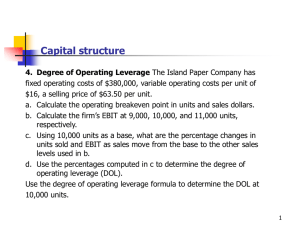

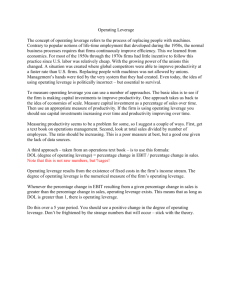

Operating Leverage The Often Overlooked Risk Factor Dr. Israel Shaked1 David Plastino, CPA/ABV Many corporate insolvency and restructuring professionals spend a large portion of their professional lives analyzing and quantifying risk, both in reorganization proceedings and litigation. For example, attorneys, financial advisors and judges are frequently called upon to decide the appropriate level of debt for a reorganized debtor, while a fraudulent conveyance action may focus on whether or not actions taken by a corporate board, creditor, or acquirer left a company in an unsustainable financial position. Risk and capital adequacy assessments performed in these situations often focus on a company’s financial leverage – defined generally as a company’s debt burden relative to the cash flow generating potential of the firm’s assets. However, this is only one element in determining whether a firm is adequately capitalized and able to support its debts. Another is the potential volatility of a company’s earnings and cash flows. By volatility we mean the probability that the company’s actual results will diverge substantially from its projected results, as well as the size of that potential divergence. All other things being equal, a company that exhibits sudden and sharp changes in its sales and cash flows can generally support less debt than a company that has been historically stable and is projected to remain so in the future. Most practitioners see volatility as a function of varying factors including, but not limited to the nature of the industry, its sensitivity to economic fluctuations, and the products produced 1 Israel Shaked is the Managing Director of The Michel-Shaked Group and professor of finance and economics at Boston University’s School of Management. He is a Coordinating Editor of the ABI Journal. David Plastino is a Senior Vice President at The Michel-Shaked Group and a Lecturer in Finance at Boston University’s School of Management. 1 by the firm. Thus, advisors and attorneys are typically aware that what constitutes “too much debt” is relative to the business and industry in question. Cyclical industries, which show regular variations tied to the economic cycle, often have less financial leverage than non-cyclical industries. Other, more stable, industries and companies can often support higher indebtedness without adverse consequences. Thus, it is common for practitioners to look to comparable companies and industry statistics for guidance in determining how much debt is appropriate for a reorganization plan, or the upper limit of reasonable financing in a leveraged buyout or recapitalization. While helpful, an analysis of industry volatility and peer company debt levels fails to fully account for the risk of a specific company. To understand why, it is first necessary to understand the nature of leverage. Leverage is any tool which magnifies the returns (both positive and negative) of a company. The most commonly understood form of leverage is financial leverage (debt), which companies use to magnify returns to equity holders. However, leverage consists of more than financial engineering. Every firm’s Total Leverage (TL) is made up of two components: Financial Leverage (FL) and Operating Leverage (OL). These two elements in combination determine the volatility of a firm’s cash flows to equity holders. In short: TL = FL + OL Financial leverage, as discussed above, generally refers to debt financing, or the way in which a firm apportions its cash flows and earnings between its debt and equity investors. Debt, which bears a fixed obligation to pay interest and principal and is superior to equity in a company’s capital structure, generally has a lower cost than equity. Thus, a company which 2 substitutes additional debt for equity by borrowing money to repurchase shares effectively increases its fixed financing costs. In good times, the cost of debt is fixed, and thus incremental cash flows go primarily to equity holders. This increases the value of the firm’s equity at a rate greater than the rate of increase in the value of the firm as a whole. In bad times, the interest and principal on the debt must still be paid, meaning that equity holders share disproportionately in the loss of firm value. A company with high debt relative to its equity is said to have high financial leverage. Attorneys, financial advisors, and the courts tend to focus on financial leverage whenever a company’s viability, or ability to continue as a going concern into the foreseeable future, is being debated. Operating leverage, which can be just as important as financial leverage, is often overlooked. Operating leverage is conceptually similar to financial leverage, except that it refers to the division of a company’s operating costs between fixed and variable elements. A company with high operating leverage has high fixed costs of operation relative to its total cost base. To understand the difference between fixed and variable operating costs, consider a manufacturer who makes rubber balls. To this manufacturer, rubber is a variable cost. As the number of rubber balls sold increases or decreases, the total amount the firm spends on rubber will vary. The cost of the company’s mortgage on its manufacturing facility, on the other hand, is a fixed cost. Regardless of the number of balls the company sells, that payment will remain the same. When sales increase, firms with higher operating leverage will enjoy faster profit and cash flow growth than less leveraged firms. Conversely, during market downturns, a firm with high operating leverage will see its margins and cash flows deteriorate more quickly. Thus, like financial leverage, operating leverage is a source of cash flow volatility and risk. 3 It is important to note that two companies with similar products, similar markets, and similar debt levels can still have substantially different degrees of operating leverage. Consider, for example, a company that owns its production facilities and production equipment versus its competitor that outsources all its production to a contract manufacturing facility. All other things being equal, when sales are rising, the second company will have lower profit margins than the first. This is because its contract manufacturer, which also has to make a living, “eats” part of the profits. During bad times, when sales decline, the second company will have better margins as it can simply purchase fewer units, while the first company still has to pay expenses related to its manufacturing facility and equipment. The second company is, in effect, giving away upside returns in good markets to partially protect it from market downswings. Thus, its volatility is lower than that of the first company. Volatility is a key component when analyzing a company’s viability and ability to continue as a going concern into the foreseeable future. To determine exactly how much the Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) of each company in the above example will vary with changes in sales requires a relatively simple analysis. First, the company’s Cost of Goods Sold and Selling, General & Administrative expenses should be separated into variable costs and fixed costs. As shown in Figure 1, both Company A and Company B have the same sales and EBIT, but Company B has higher variable costs, while Company A has higher fixed costs. Sales minus variable costs is known as Contribution Margin. Contribution Margin represents the amount available to cover all other expenses and distributions after variable costs of producing a product have been paid, and can be expressed as either a dollar value or a percentage. In our example, the Contribution Margin for Company A is $700,000, or 70%, and the Contribution Margin for Company B is $550,000, or 55%. 4 FIGURE 1: Company A $1,000,000 300,000 700,000 200,000 500,000 Sales - Variable Costs = Contribution Margin - Fixed Costs = EBIT Company B $1,000,000 450,000 550,000 50,000 500,000 We can then utilize the following formula to compute each company’s Degree of Operating Leverage: Degree of Operating Leverage (DOL) = Contribution Margin (CM) CM – Fixed Costs (FC) The computation of the Degree of Operating Leverage for each company is shown in Figure 2. The equation derives a DOL of 1.4 for Company A and 1.1 for Company B. The DOL tells a user by how much EBIT will change for every $1 change in sales. FIGURE 2: Company A DOL = CM CM - FC 700,000 = 700,000 -200,000 Company B 1.40 550,000 550,000-50,000 = 1.10 Now consider the following example, illustrating a downside case scenario in which sales at both Company A and Company B decline from $1,000,000 to $750,000, a 25% drop. Assuming that this decline is due to a decrease in volume, not selling price, each company’s variable costs and Contribution Margin will remain the same percentage of sales. Fixed costs at both companies will remain the same, thus becoming a larger percentage of sales. EBIT will 5 decline to $325,000 and 362,500, respectively (see Figure 3). Therefore, Company A’s EBIT has declined by $175,000, or 35%, and Company B’s EBIT has decline by $137,500, or 27.5%. FIGURE 3: Sales - Variable Costs = Contribution Margin - Fixed Costs = EBIT Company A $750,000 225,000 525,000 200,000 325,000 Company B $750,000 337,500 412,500 50,000 362,500 These detailed computations produce the same result as multiplying the decline in sales (25%) by the DOL factors computed above. Percentage Change in EBIT = Change in Sales * DOL Company A Percentage Change in EBIT = -25% * 1.4 = -35% Company B Percentage Change in EBIT = -25% * 1.1 = -27.5% While we discuss traditional manufacturing companies in the example above, it is important to note that almost all firms, regardless of the industry they are in, have both fixed and variable costs. Whenever both fixed and variable costs exist in a company’s operational structure, this framework can be utilized. Use of DOL factors proposed above can provide a number of advantages to a bankruptcy professional. First, they give an easy and intuitive way to stress test “base case” financial projections that are often prepared in connection with deals and reorganization plans. Such projections often apply fixed margins to sales to derive EBIT and cash flows. However, as 6 shown above, margins do change. In fact, the higher the percentage of fixed costs in the company’s cost structure, the more variance there will be in margins under both upside and downside scenarios. Realizing this, many advisors reduce a company’s margins when performing stress tests. Often, these margin reductions are subjective estimates, or are based on the company’s historical margin fluctuations. Such analyses require significant judgment and can therefore produce misleading results. Companies often appear in bankruptcy court because they have undergone significant changes. A reorganized company, for example, may have been able to significantly reduce its fixed costs through the bankruptcy process by rejecting contracts and leases. Relying on historical margin fluctuations would, in such cases, overestimate the operating risk of the company. In leveraged buyouts (including failed LBOs) the acquiring company often intends to change the acquired firm’s operations significantly through both cutting costs, outsourcing production, or expanding operations. These changes could lead to higher or lower fixed costs and, therefore, to higher or lower margin volatility than would be indicated by the company’s historical results. DOL factors can take these changes into account, as long as they are computed using the mixture of fixed and variable costs that will apply over the projection period being assessed. In summary, it is our opinion that many cases of bankruptcy and financial distress could benefit from a more careful examination of operating leverage. Despite its importance to the volatility of a firm’s cash flows, operating leverage is often overlooked, or improperly analyzed. Utilizing the equation presented in this article to compute a company’s Degree of Operating Leverage is a one-time investment that can allow a bankruptcy practitioner to quickly assess the 7 operational risk of a company. With a DOL factor in hand, it is then easy for a practitioner to calculate EBIT under any given sales forecast without stepping through a full financial analysis. That, in turn, can enable better decisions, and help ensure that the subject company’s liabilities are structured in such a way as to ensure that it remains a viable, going-concern entity. 8