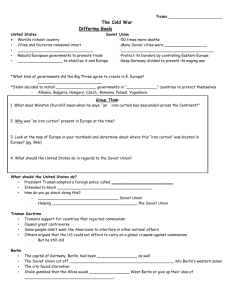

old War notes

advertisement

Cold War The term “Cold War” did not come into common use until it was used by Bernard Baruch, who was an adviser on foreign affairs to President Harry S. Truman and had also been an adviser to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson before that. In a speech to the South Carolina Legislature on 16 April 1947, Baruch said: Let us not be deceived — we are today in the midst of a cold war. Our enemies are to be found abroad and at home. Let us never forget this: Our unrest is the heart of their success. The peace of the world is the hope and the goal of our political system; it is the despair and defeat of those who stand against us. The phrase “Cold War” was then picked up by U.S. media to describe the relationship between the USA and the USSR: a war without fighting but still a battle. The widely respected journalist en essayist Walter Lippmann played an important role in popularizing the term through a series of articles on the Cold War. – Historians have sharply disagreed as to who was responsible for the Cold War, and whether the conflict was inevitable or could have been avoided. Why did the conflict emerge? 1. The traditionalist vision Until the 1960s, the traditionalist vision was predominant. The traditionalists placed the responsibility for the Cold War on the expansionist policy of the Soviet Union under Stalin, shortly after the Second World War. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union tried to dominate its neighbors and set up a sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. The aggressive intentions of the Soviet Union were, among other things, reflected by the Communist coup in Czechoslovakia, the Berlin Blockade and the attack by North Korea on South Korea in 1950. According to the traditionalists, it was this Soviet expansionist policy that forced the United States to intervene, which subsequently led to the Cold War. 2. The revisionist vision However, a new account emerged in the wake of the Vietnam War. U.S. involvement in Vietnam disillusioned some historians and created antipathy towards the American position. In the 1960s and 1970s, the revisionists stressed that American expansionism was the cause of the Cold War. They pointed out that, at the end of the Second World War, the Soviet Union was severely weakened, whereas the United States prospered and possessed a monopoly on the atomic bomb. According to the revisionists, Stalin’s main priority was to recover from the devastating war years. They placed the cause of the Cold War in the nature of capitalism and viewed Marshall Aid as a way of seeking new markets and expanding the U.S. economy. The Soviet Union thus correctly understood that their sphere of influence in Eastern Europe was in danger 3. The post-revisionist vision The revisionist vision produced a critical reaction of its own. In the 1970s and 1980s, a group of historians called the post-revisionists argued that the foundations of the Cold War were neither the fault of the U.S. nor the Soviet Union. They viewed the Cold War as something inevitable. According to the post-revisionists, the Cold War emerged from the power vacuum after World War II, when the European countries were severely weakened by the war. The multipolar situation that had existed before the war had given way to a bipolar world. For both the United States and the Soviet Union it was unacceptable to let the other superpower dominate Europe, as this would seriously disrupt the balance of power. Conflict over spheres of influence was therefore an inevitable result of considerations of national security. How did this conflict evolve? The Greek civil war and the Truman Doctrine After the evacuation of German forces from Greece in 1944, there were two groups in that country that wanted to take power: the monarchists and the Communists. A civil war soon developed. The Communists were supported by the Soviet Union, and, after the end of the Second World War, also by Yugoslavia, Albania and Bulgaria. Britain and the United States supported the monarchists. The involvement of the United States in the Greek civil war marked a new era in their attitude towards world politics. The new approach became known as the “Truman Doctrine” and it would guide U.S. diplomacy for the next forty years. The doctrine was established on 12 March 1947, when President Harry S. Truman delivered a speech before Congress in which he called for the allocation of $400 million in military and economic assistance for Greece and Turkey. In his speech, Truman declared: ”It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” The Marshall Plan and Czechoslovakia In accordance with the Truman Doctrine, the United States enacted the “Marshall Plan.” Officially entitled the European Recovery Program (ERP), the initiative was soon named after the American General George C. Marshall who had been sent to assess the economic state of Europe after WWII. In June 1947, Marshall suggested that about $17 billion was needed to rebuild Europe’s prosperity. He stated that: “Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.” The Marshall Plan did not only offer monetary support to the western European states, but also to the Soviet Union and its allies. However, Stalin looked upon the reconstruction plan with suspicion and prevented the eastern European states from applying for Marshall Aid. In Stalin’s view, economic integration with the West would weaken his hold on Eastern Europe. Upon his return from a meeting with Stalin on the matter of Marshall Aid, Czechoslovak foreign minister Jan Masaryk stated: “I went to Moscow as the foreign minister of an independent sovereign state. I returned as a lackey of the Soviet government.” Initially, the U.S. Congress refused to grant the necessary $17 billion for the Marshall Plan, but the American attitude changed when the Communists took over Czechoslovakia in March 1948. Up until then, Czechoslovakia had retained democratic structures and pursued policies independent of Moscow. The brutality of the Communist coup shocked the Western powers. Foreign minister Jan Masaryk was found dead below his open window. Communist investigators concluded that he had committed suicide, but the American’s assumed he was pushed. Immediately, the American Congress approved the Marshall Plan The Marshall Plan in Belgium The Berlin Blockade and the Berlin Airlift Late 1946, Britain and the United States had combined their German occupation zones in “Bizonia.” When, in June 1948, they introduced currency reforms in the western zones of Germany, Stalin responded by instituting the Berlin Blockade. Berlin was deep in the Soviet zone and was linked to the western zones by vital roads, railways and canals. Stalin blocked all these supply lines, preventing food and materials from arriving in West Berlin. The only way into Berlin was by air. The Truman administration therefore reacted to the Berlin Blockade with a continual daily airlift that brought food and supplies to the people in West Berlin. Ten months later, it was clear that the Western Allies would not give up Berlin. On 12 May 1949, Stalin backed down and lifted the blockade. In April 1949, France merged their occupation zone with those of Britain and the United States in what now became “Trizonia.” Soon after the Berlin Blockade was lifted, two separate German states were created: the Federal Republic of Germany (or West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (or East Germany). Formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization NATO At the height of the Berlin Blockade, the United States, Canada, and ten West European countries met in Washington and signed an agreement to work together. The new organization they formed on 4 April 1949 became known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). One of the key points was the principle included in Article 5. “An armed attack against one or more of [the member states] in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defense recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.” How is/was this conflict perceived at the time and since? George Kennan’s Long Telegram, 22 February 1946 On 22 February 1946, George F. Kennan, the chargé d’affaires at the American Embassy in Moscow and an expert on Russia, sent the longest telegram in State Department history. In the “Long Telegram,” as it became known, Kennan presented an analysis of Soviet policy that, over the next year, heavily influenced the Truman administration’s Cold War policies “In summary, we have here a political force committed fanatically to the belief that with U.S. there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted, our traditional way of life be destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken, if Soviet power is to be secure. This political force has complete power of disposition over energies of one of the world’s greatest peoples and resources of the world’s richest national territory, and is borne along by deep and powerful currents of Russian nationalism. In addition, it has an elaborate and far-flung apparatus for exertion of its influence in other countries, an apparatus of amazing flexibility and versatility, managed by people whose experience and skill in underground methods are presumably without parallel in history.” Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech 5 March 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his “Iron Curtain” speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. This is an excerpt of the Iron Curtain speech: From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow. (…) The Communist parties, which were very small in all these Eastern States of Europe, have been raised to pre-eminence and power far beyond their numbers and are seeking everywhere to obtain totalitarian control. Police governments are prevailing in nearly every case, and so far, except in Czechoslovakia, there is no true democracy. (…) Whatever conclusions may be drawn from these facts – and facts they are – this is certainly not the Liberated Europe we fought to build up. Nor is it one which contains the essentials of permanent peace. Stalin’s reaction to Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech Ten days after Winston Churchill spoke of an Iron Curtain having descended across Eastern Europe, the Soviet daily Pravda published an interview in which Stalin criticized the former prime minister’s though stance: As a result of the German invasion, the Soviet Union has irrevocably lost in battles with the Germans, and also during the German occupation and through the expulsion of Soviet citizens to German slave labour camps, about 7,000,000 people. In other words, the Soviet Union has lost in men several times more than Britain and the United States together. (…) One can ask therefore, what can be surprising in the fact that the Soviet Union, in a desire to ensure its security for the future, tries to achieve that these countries should have governments whose relations to the Soviet Union are loyal? How can one, without having lost one’s reason, qualify these peaceful aspirations of the Soviet Union as ‘expansionist tendencies’ of our government? (…) Mr. Churchill wanders around the truth when he speaks of the growth of the influence of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe. (…) The growth of the influence of Communism cannot be considered accidental. It is a normal function. The influence of the Communists grew because during the hard years of the mastery of fascism in Europe, Communists showed themselves to be reliable, daring and self-sacrificing fighters against fascist regimes for the liberty of peoples. The Soviet Ambassador to the United States on post-war American policy On 27 September 1946 (seven months after George Kennan had sent the Long Telegram to his colleagues in Washington), Soviet Ambassador to the United States Nikolai Novikov presented his analysis of American policy: The foreign policy of the United States, which reflects the imperialist tendencies of American monopolistic capital, is characterized in the post-war period by a striving for world supremacy. This is the real meaning of the many statements by President Truman and other representatives of American ruling circles; that the United States has the right to lead the world. All the forces of American diplomacy – the army, the air force, the navy, industry, and science – are enlisted in the service of this foreign policy. For this purpose broad plans for expansion have been developed and are being implemented through diplomacy and the establishment of a system of naval and air bases stretching far beyond the boundaries of the United States, through the arms race, and through the creation of ever newer types of weapons. The Warsaw Pact reconsidered Stigmatized as a ‘cardboard castle’ by NATO officials upon its conception in 1955, the Warsaw Pact has long been viewed as a mere transmission belt of the Soviet Union. However, recent archival research has shown that whereas the Soviet Union still determined Warsaw Pact dynamics in the early 1960s, it was no longer positioned at centre-stage from 1965 onwards. The period between 1961 and 1964 witnessed the emancipation of several individual non-Soviet-Warsaw-Pact (NSWP) leaders. This document is a transcript of a speech by Bulgarian First Secretary Todor Zhivkov at the 1961 Political Consultative Committee (PCC) meeting in Moscow. Two themes dominate his speech: the state of Bulgaria's defense capabilities and the criticism directed toward the Albanian government for failing to inform the Warsaw Pact member states about the alleged attack on Albanian territory at the Vlorë naval base by NATO forces. The period from 1965 to 1968 heralded the emancipation of the Warsaw Pact as an alliance in its own right. These Romanian minutes of the 1965 Political Consultative Committee (PCC) meeting in Warsaw address Romania's disagreement with the possible deployment of a multilateral nuclear force in Western Europe. Contrary to all other participants, the first secretary of the Romanian Workers' Party, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, opposes the idea of a nuclear weapons non-proliferation treaty. He fears that certain countries could easily use a non-proliferation treaty to condemn China's nuclear arsenal. The PCC meeting in 1969 contained the simultaneous culmination of all the conflicts that had dominated the Warsaw Pact in the second half of the 1960s, such as Warsaw Pact reforms and the appeal for a European Security Conference. On 18 March 1969, at a meeting of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party, Romanian leaders Nicolae Ceausescu and Emil Bodnaras inform their colleagues of the proceedings of the 1969 PCC meeting held in Budapest. http://historiana.eu/case-study/cold-war/mutually-assured-destruction#