Women's Suffrage Paper

advertisement

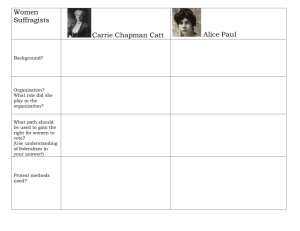

The Transformation of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States, 1912-1920 It was on August 18, 1920 that the state legislature of Tennessee ratified the Nineteenth Amendment granting women the right to vote across the United States. What had seemed like an endless fight to leading crusaders such as Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt swiftly came to an end. Catt, leader of the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was astonished that the ratification of the amendment had come so quickly. She had been prepared to fight for the passage of a suffrage bill well beyond the August 1920 ratification date (Buechler, 208). That she was surprised is not such a crazy notion. Between the years of 1912 and 1920, the women’s suffrage movement blossomed and became a much more viable movement at an astounding rate. To fully understand how the ratification of the Nineteen Amendment occurred only eight years after the heated 1912 presidential elections, the viewpoints of the two main contenders in the 1912 election, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, will first be examined. Secondly, the social climate of the time period will be discussed, and lastly, the impact of WWI upon the women’s suffrage movement will be appraised. The presidential elections of 1912 consisted of four different opponents from four different parties: William H. Taft, Republican, T. Woodrow Wilson, Democrat, Theodore Roosevelt, Progressive, and Eugene V. Debs, Socialist. All four candidates were powerful men who had strong platforms and supporters, but the two contenders who stood out the most with the American public were Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. These two candidates stood out because they were in the middle of the spectrum as far as the amount of structural change each candidate and party wanted to enact. To the far right of that spectrum was the Republican candidate Taft who did not want to make any changes to the system as it was in 1912. In contrast, to the far left of the spectrum was Socialist candidate Debs who wanted 1|Page revolutionary structural change. Nestled between these two candidates were Democrat candidate Wilson who wanted mild structural change, and Progressive candidate Roosevelt who wanted serious structural change. When it came to the issue of women’s suffrage, Wilson and Roosevelt had two different perspectives. Wilson regarded women’s suffrage to be a question for the states (Cooper Jr., 178). Many states had passed suffrage legislation prior to the 1912 elections, and in 1912 alone three states, Oregon, Arizona, and Kansas, had all passed legislation giving women the right to vote (Ayers, 696). As Buechler points out, “[i]t is only with the benefit of hindsight that these state victories appear to be a steady march of progress in the suffrage fight. (Buechler, 56). NAWSA, the leading suffrage organization in the United States, was in constant conflict over whether to fight for suffrage at the state or national level throughout its existence. At the time, winning state victories wasn’t enough for NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt and her supporters, true victory would only be experienced after national suffrage was achieved. Roosevelt and the Progressives endorsed nation-wide woman suffrage, although this did not mean Roosevelt himself necessarily wanted to remedy the social discrimination of women in American society (Cooper Jr., 176 & 179). Perhaps if Jane Addams, a strong supporter of Roosevelt and the suffrage movement had known this, she would not have endorsed him so strongly in the campaign. In the long run, the issue of woman’s suffrage was largely lost in the mix of a variety of other issues such as the tariff and the extent of reform each candidate wanted to make. Woodrow Wilson’s victory in the 1912 election did not mean that women had lost any of their drive and commitment to national women’s suffrage. Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, two of the more radical members of NAWSA, organized a substantial woman suffrage parade on the 2|Page same day as President Wilson’s inaugural celebration in April 1913 (Buechler, 56). The suffrage movement continued to gain a larger audience, although there was a schism within NAWSA, with Paul and Burns forming the Congressional Union (CU) in early 1914.* The division was largely caused by the approach each faction wanted to take to achieve national suffrage. NAWSA, led by Catt, saw a state-by-state approach as the best strategy whereas Paul and Burns demanded national suffrage exclusively, unwilling to compromise. While there was a great deal of turmoil within the suffrage movement, there was also a great deal of social change occurring for women at the turn of the century. There were many more possibilities for a young woman during the 1900s than her mother before her. A young woman in the 1900s would be better educated, more likely to hold a professional job before marriage, and to live in a nice single family apartment after marriage, things her mother never had in life (Sochen, 260). Between 1900 and 1910, the number of women in the workforce grew from 23.5% to 28.1% (Cooper Jr., 203). From this time on, the female workforce continued to grow, but the biggest change came in the kinds of jobs a woman held. More and more women were becoming secretaries, school teachers, social workers and other jobs that held social prestige. While changes were occurring in the workplace, there were even more changes occurring for American women and families. The divorce rate was rising and the size of the average family was decreasing, with 1 of every 9 marriages ending in divorce, and by 1920, the average number of 2 – 3 children per mother compared to larger numbers in previous decades. Victorian views of sexuality were quickly changing as more young people began to engage in premarital sex, although it is noted that the occurrence was still considerably low, especially compared to *The CU later changed its name to the National Women’s Party (NWP) in 1917. 3|Page today (Ayers, 756). Other changes in the behavior and appearance of women across the country were evident. The ideal woman was full of life, personified by the “Gibson Girl.” More women were driving cars and spending time outdoors. Soon, women’s fashions were changing. Skirtlengths began to rise from the ankles to mid-calf by 1915, and bobbed hair, which first made an appearance in 1912, was all the rage by 1914 (Cooper Jr., 204-205). More and more women began to wear cosmetics and smoke cigarettes, two things that were most commonly reserved only for women of the brothel before 1910. Female sexuality was increasingly being addressed in popular culture, and women such as Margaret Sanger crusaded for birth control, which was very radical to Americans and to most women at the time. America and women in particular were experiencing a major cultural revolution. As Buechler notes, women’s movements, emerged during periods of overall political and cultural rebellion that provided the ideological space, movement resources, and political opportunity of such activity… When women’s movements have been able to argue for and from sameness and difference, for equal rights and special contributions, and for justice and expediency, mass movements of women have emerged and thrived (Buechler, 89). As women gained a larger role and status in American society, the suffrage movement continued to find women to join its ranks. One factor that was very important is the people the movement was made up of. No longer was it just upper class educated women fighting for the right to vote, the movement was quickly gaining momentum across class lines. Involvement in the movement alone was a major change for a woman and American society. To gain more popularity with all Americans, suffrage leaders tried to minimize the worries of the old guard. At the time, people were scared that granting women the right to vote would cause major changes upon the social landscape. People 4|Page opposed to suffrage predicted the downfall of the American family, whereas supporters of the movement predicted that the inclusion of women in the voting process would uplift and purify politics, creating a more moral country (Sochen, 244). Soon another argument would be used to support women’s suffrage, the involvement of women in WWI. When war broke out in Europe in 1914, the extent and impact of going to war was severely underestimated. What was supposed to be a “short summer war,” quickly turned into one of the most devastating events in the history of the world (Sochen, 264). Woodrow Wilson’s 1916 presidential victory was based on his vow to keep the United States out of what was regarded as a European war, declaring neutrality. As American economic support continued to grow for the British, and hostilities continued to grow with the Germans, the British and other allied powers pressured the United States to enter the war and end the stalemate between the allies and central powers. By April 1917, the United States declared war in Germany. The United States was now a part of the war Wilson vowed to keep it out of. Carrie Chapman Catt and NAWSA quickly saw the involvement of women in the war effort as being a catapult for the victory of women’s suffrage. Catt argued that a woman’s vote could offset a “slacker’s vote,” one who was disloyal to the United States and opposed the war. NAWSA quickly began to ask for suffrage as a “war measure” to repay women for their contributions during WWI (Ayers, 770). Catt and NAWSA’s more radical counterparts Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party (NWP) took a much different approach. Still infuriated at Wilson for not supporting national suffrage during his 1916 presidentail campaign, the NWP set out to embarrass and abhor Wilson and the Democrats. Picketers would stand outside of the White House holding signs 5|Page stating, “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” (Ayers, 771). Paul questioned how Americans could be in France fighting for democracy when there was no democracy for the women of America. It is the tactics of both groups during WWI that eventually led to the passage of a suffrage amendment in the House of Representatives in 1918. Wilson eventually came out as a supporter of the amendment prior to the Congressional elections that year. “We have made women partners in the war,” Wilson argued while addressing the Senate on September 30, 1918, “shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” (Cooper Jr., 308). In October, the amendment was fell two votes short of the two-thirds necessary to pass the Senate. There was predictable hesitance on behalf of the Southern states to adapt a women’s suffrage amendment. In an effort to gain southern votes, politicians and activists tried to reassure Southerners that the amendment did not threaten white supremacy in the South. Women’s suffrage meant “the removal of the sex restriction, nothing more, nothing less” (Keyssar, 175). Eventually, it was the ratification of women’s suffrage by a Southern state (Tennessee) that led to the enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment in August of 1920, giving women in the United States the right to vote. Women were quickly going to be exercising their right to vote as 1920 was a presidential election year. After a tumultuous decade, Americans yearned for a return to “normalcy,” and it is perhaps because of this yearning that the addition of women to the electorate did not cause the massive social change that was predicted by both sides of the suffrage movement. Keyssar points out, there was little change in partisan or voting patterns, and women did not turn out to the polls in droves either. Fewer women voted than men in the 1920 election, and they voted 6|Page overwhelmingly for Republican Warren G. Harding. “Political life in the 1920s was not nearly as vibrant or energetic as it had been in the 1890s or the latter years of the Progressive era; despite the identification of women with social reform, reforms were few during the first decade that women could vote” (Keyssar, 176). Due to the lack of great social change caused by the enfranchisement of women, some historians view the greatest significance of the suffrage movement as being the first major step towards a change in women’s role and place in society. “It was the first independent movement of women for their own liberation. Its growth—the mobilization of women around the demand for the vote, their collective activity, their commitment to gaining increased power over their own lives—was itself a major change in the condition of those lives” (DuBois, 17-18). The swift chain of events that took place between 1912 and 1920 in the women’s suffrage movement led not only to the enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment, but an era of conservatism in the United States. The elections of 1912 transpired in the midst of major social changes for women in American society. As America entered WWI, the voices of organizations such as NAWSA and NWP increased, and by 1920 the fight for women’s suffrage had come to an end, as well as the fight for major reforms. These eight years had proved to be too turbulent for a majority of the American public, and women would have to wait over 40 years before a mass women’s movement gained popularity in the United States on the scale that it did between 1912 and 1920. 7|Page Works Cited and Consulted Ayers, Edward L. et al. American Passages: A History of the United States. Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc., 2000. Buechler, Steven M. Women's Movements in the United States: Woman Suffrage, Equal Rights, and Beyond. Newark, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990. Cooper Jr., John Milton. Pivotal Decades: The United States, 1900-1920. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1990. DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848-1869. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978. Fleming, Thomas. The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I. New York: Basic Books, 2003. Keyssar, Alexander. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books, 2000. Lears, Jackson. Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877-1920. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009. McInerney, Thomas. Lecture. Metropolitan State College of Denver, 31 Mar. & 5 Apr., 2011. Sochen, June. Herstory: A Woman's View of American History. New York: Alfred Publishing Co., Inc. , 1974. 8|Page