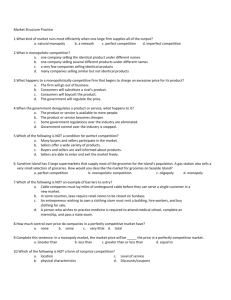

Evans_Groceries_Order

advertisement

The Groceries Order Monday, April 2nd 2007 John Evans The Competition Authority Overview What was the Groceries Order? History of the Groceries Order(s) The Groceries Order Debate Competition Authority Arguments Life after the Groceries Order Concluding Comment What was the Groceries Order? GO as an RPM Mechanism 1. The Grocery Order prohibited the resale of certain grocery goods, along all stages of the supply chain, below the invoice price for those goods: In effect the Grocery Order was a Resale Price Maintenance (RPM) Mechanism; The practice of RPM, in any market, is typically regarded as anticompetitive; Enforced by the Office of the Director of Consumer Affairs. 2. Example: consider a jar of baby food: Invoiced at €2.00 by a wholesaler to a retailer; Retailer receives end of year off-invoice loyalty discount worth €0.20 per jar; The retailer has to charge a minimum resale price equal to the net invoice price of €2.00; But, the real cost to the retailer of €1.80 – protected margin is €0.20. 3. Restricts Competition - how? Wholesaler from the example, can effectively set the retail price for different retailers that it trades with – thereby restricting competition among retailers; But, negotiate different discounts with different retailers. History of the Groceries Order The Early Orders - 1956 1. The 1956 Order (came into effect in 1958) following a recommendation from the Fair Trade Commission (FTC). 2. The Order applied to a variety of grocery goods and contained provisions that: Prohibited RPM; Prohibited collective price fixing by suppliers and wholesaler (at the time many retail prices were set by the State); 3. Prohibited refusal to supply based on supplier dissatisfaction with resale price; But allowed refusal to supply where retailers resold below the wholesale price; Also contained ‘fairness’ provisions – but allowed suppliers to distinguish ‘classes’ of customers. Competition: Some pro competitive elements to the 1956 Order; But, competition among retailers restricted by the state to significant extent through price controls; Motivation was some notion of ‘fairness’ relating to producers, not consumers. The Early Orders - 1973 1. 1966 FTC review of grocery trade – no change despite call for ban on sales below cost. 2. In 1970, following a large number of complaints from the industry, the FTC undertook another review of the grocery trade: The FTC reported in 1972 and a new Order was enacted; 1973 Order banned advertising of sales below cost for food groceries; But not sales below cost; 1973 Order did not revoke the 1956 Order, but amended it so that suppliers could not refuse to supply food groceries. 3. Context: At this point supermarkets had arrived and ‘multiples’ were developing; Pressure from many quarters but especially from small retailers for protection; For example, RGDATA wanted a ban on sales below cost plus 5%. 4. FTC rejected, for the third time, calls for a ban on sales below cost anticipating that: Defining ‘below cost’ would be difficult; It would restrict competition. Early Orders – 1978/1981 1. The Restrictive Practice Commission (which had replaced the FTC) conducted reviews in 1975 and 1978, leading to the enactment of two Orders in 1978. 2. First 1978 Order - Fresh and frozen foods removed from the scope of the Orders. 3. Second 1978 Order: Reinstated provisions allowing suppliers to refuse to supply where resale was below cost; Introduced a definition of below cost selling as selling below ‘the net invoice price’ (did not account for off-invoice discounts and rebates). 4. 1980, RPC again considered and rejected banning sales below cost, but 1981 Order strengthened provisions relating to the advertisement of sales below cost. The 1987 Groceries Order 1. Another review by the RPC in 1986: Considered that the ban on advertising of sales below cost had become ineffective; Recommended ban on sales below cost. 2. Context: Price war “put H. Williams out of business’’; RPC criteria appears to have been based on notions of ‘fairness’ (for producers). 3. The RPC did: Recognise that the definition of ‘cost’ as the ‘net-invoice price’ was inadequate; Accept that there was a trade off between protecting producer interests and restricting competition: “Although we have examined the effects of a prohibition in considerable detail, they are difficult to predict with certainty….We cannot overlook however, the views of manufacturers and independent retailers that it would make a significant difference to them” The Groceries Order Debate Leading up to the Removal 1. 1991 Review by RPC Recommended removing the ban; Minority report by Myles O’Reilly. 2. 1991 Competition Law introduced: Contained provisions relating to the abuse of a dominant position (Section 5) In particular, relating to predatory pricing. 3. 1993 and 1995 Internal Review by Department of Enterprise, Trade and employment – recommended removing the Order 4. 1996 Competition and Mergers Review Group were divided – majority were in favour of removal. 5. 2005 Public Consultation on the Groceries Order – Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment. Arguments for the Retention of the Order 1. The ‘Food Deserts’ argument: The removal of the Order will result in elimination of small shops from the retail landscape undermining vibrant town centres and creating urban and rural food deserts. 2. The ‘Employment’ argument: The removal of the Order will result in a loss of jobs in the grocery trade. 3. The Consumer Protection Argument: The removal of the Order will allow large multiples to engage in predatory conduct, drive smaller shops from the market and ultimately raise prices. Consumer Strategy Group Report 2005 “Since 1987, the Groceries Order (GO) has prohibited selling many items at below the invoiced price. This measure was introduced in order to protect smaller independent stores who could not compete efficiently with large multiples directly on cost. The number of independent grocery retail outlets declined considerably between 1977 and 2002.” “Many arguments have been put forward for both the retention and the abolition of the Groceries Order, but the current situation operates against the interests of consumers.” National Consumer Agency “Consumer demand for convenience shopping indicates that there is no reason to believe that independent shops and chains will not continue to service both rural and urban communities.” “There have been several reviews of the Groceries Order since 1987, and most have concluded that the Order is a bad deal for Irish consumers. The Groceries Order is now well past its sell by date. It should be abolished so that the consumer can benefit.” National Competitiveness Council “Ireland’s ascent through the consumer pricing ranks is partly due to fluctuations in the value of the euro, which is out of the control of Irish policy makers. But it also stems from high domesticallygenerated prices, particularly in the non-traded services sector. Decisions by government, its agencies and regulators have also contributed adversely to inflation. This has damaging implications for the enterprise sector and the ability of Irish firms to compete in foreign markets.” Chambers of Commerce of Ireland “… this is a highly complex issue, the key points of which have been obscured in the debate to date. CCI agrees with retailers that below-cost selling is wrong. However, our analysis suggests that the Groceries Order does not address this issue at all. Rather it is a ban on below invoice cost selling – an anti-competitive practice that prohibits businesses from passing on to the customer, discounts that they receive from suppliers in the form of an end of year invoice.” Competition Authority Arguments Three Separate Headings 1. Object - the primary objective of the Groceries Order is to restrict competition: Reduces competition at the retail level by restricting retailers’ scope to compete on price; Weak competition at the retail level tends to feed back up the chain of distribution – to wholesalers, manufacturers, producers etc. 2. Effect - the effect of the Groceries Order is to reduce competition and increase prices (tends to impact lower income groups disproportionately); and, 3. Proportionality - the Groceries Order does not meet and is not necessary to achieve the claimed benefits. Price Index on Food and Drinks Consumed at Home (June 01- June 05) For € 100 spent in June 2001 Overall Items Covered by the Order Items Not covered by the Order 2001 100.0 100.0 100.0 2002 103.1 103.7 101.4 2003 102.4 107.0 100.9 2004 100.1 107.5 99.4 2005 98.9 107.4 94.9 4.5% 7.4% -5.1% % Growth Over period Source: Derived from CSO data (rebased by The Competition Authority) Income groups from lowest 10% of households to top 10% of households 0 -10% 10%20% 20%30% 30%40% 40%50% 50%60% 60%70% 70%80% 80%90% 90%100% Average Househol d A Weekly food costs in June 2005 €43.23 €64.47 €80.29 €88.21 €99.39 €109.4 4 €114.9 1 €125.9 2 €132.89 €148.38 €100.74 B Food costs without Groceries Order (June 2005) €39.25 €58.54 €72.91 €80.11 €90.26 €99.39 €104.3 5 €114.3 5 €120.68 €134.75 €91.49 C Weekly savings in June 2005 €3.97 €5.92 €7.38 €8.10 €9.13 €10.05 €10.56 €11.57 €12.21 €13.63 €9.25 D Annualised Savings 2005 €206.4 9 €307.96 €383.5 4 €421.3 9 €474.8 0 €522.8 1 €548.9 1 €601.5 0 €634.82 €708.82 €481.25 E Weekly June 2005 €130.7 7 €214.71 €307.0 4 €408.4 5 €520.7 3 €635.1 1 €760.4 6 €915.1 9 €1,139.3 2 €1,758.7 4 €679.02 F Saving as % weekly budget 3.04% 2.76% 2.40% 1.98% 1.75% 1.58% 1.39% 1.26% 1.07% 0.78% 1.36% G Saving to the economy (2005) budget of Source: Analysis of The Competition Authority based on CSO data €577.49 million Proportionately 1. Foods deserts arguments and Employment arguments. 2. Predatory pricing arguments: 3. The plausibility of the alleged predation - ex ante and an ex post analysis – does the alleged predation makes economic sense - market facts - Did the alleged victim go out of business? Did prices drop dramatically only to be raised subsequently? A business justification – if there is a plausible case, could there be other plausible explanations? Feasibility of recoupment – can short term losses can be recovered through charging higher prices in the medium to longer term? Depends on entry conditions and ultimately dominance. Pricing below cost – what measure of cost? A simple ban on sales below some ad hoc measure of cost will on balance be anticompetitive. The American economist Harold Demsetz wrote: "The attempt to reduce or to eliminate predatory pricing is also likely to reduce or eliminate competitive pricing beneficial to consumers." Colm McCarthy “The basic scary story goes like this. If big bad retailers are free to cut prices, without the restraint of the Groceries Order, they would do so with ferocity, drive out the smaller competitors (ultimately all competitors), just one would survive and this rapacious monopolist would then screw the consumer for ever more. The story has been around since about the Eighties, and the beginnings of pro-competition and antitrust legislation in the US and Europe. While not quite as venerable as the Grimms' Fairy Tales, the predatory-pricing bogeyman is out of the same tradition, and has about as much evidence to support it. Can you think of a single monopoly currently screwing Irish consumers which won its position through a successful predatory pricing campaign” The Removal of the Order 1. In 2005 – confluence of consumer interests: National Consumer Agency; Competition Authority; OECD; Consumer Strategy Group; National Competitiveness Council; Eddie Hobbs! 2. Interesting from an Irish political economy point of view – Consumer v. Producer Interests. 3. The Order was finally removed on March 20th 2006. Life after the Groceries Order The Grocery Monitor 1. Ministerial Request and the 2006 Social Partnership 2. Unusual Request: To monitor on an ongoing basis; Unusual for an ex ante regulator; But perhaps not surprising given the history – multitude of reports and review groups. 3. The 4. Grocery Monitor – three aspects: Market structure at Retail and Wholesale levels; Business Practices – Pricing behaviour and Vertical Integration (franchise arrangements); and, Barriers to Entry and Expansion. At a minimum – aim is to raise the level and nature of public debate by putting the appropriate information in the public domain. Level 1: Producers, manufacturers, imports etc… Supply Level 2: Wholesale Cash and Carry Non-affiliated wholesalers Wholesale divisions of franchise groups Verticallyintegrated retailers Level 3: Retail Non-affiliated stores: ‘convenience’ stores Forecourt stores Retail Franchise Operation of franchise groups/Franchisee: ‘one stop’ stores ‘convenience’ stores Forecourt stores 103 CPI 102.5 102 101.5 Non-GO Items 101 Non-GO and GO Items 100.5 100 99.5 99 GO Items 98.5 98 Apr-06 May-06 Jun-06 Jul-06 Aug-06 Sep-06 Oct-06 Nov-06 Dec-06 Jan-07 Feb-07 Concluding Comment Concluding Comment 1. Between 1956 to 1987, Government policy in relation to the grocery reversed – largely due to consistent lobbying by producer interests: Only one of the multitude of reports and reviews recommended a ban on below cost selling; It took a further 19 years to reverse it again. 2. The nature of the debate changed over time: From one concerning notions of ‘fairness’ among producers; To a more consumer focused debate. 3. The Groceries Order was a ‘public’ restriction on competition – what if were ‘private: Possibly criminal under Competition Law; See Ford Dealers case – €30,000 fine plus twelve months suspended sentence. Useful References 1. Department of Enterprise Trade and Employment (2005), The Restrictive Practices (Groceries) Order 1987: A Review and Report of Public Consultation Process. 2. Forfas (2004), National Competitiveness Council - Annual Competitiveness Report. 3. Consumer Strategy Group (2005), Consumer Strategy Group Report: Making Consumers Count. 4. Collins A, and Oustapassidis K. (1997), Below Cost Legislation and Retail Performance, Agribusiness Discussion Paper No 15. 5. Walsh P.P, Whelan C. (1999), A Rationale for Repealing the 1987 Groceries Order in Ireland, The Economic and Social Review, Vol.30, No.1, pp.71-90. 6. Walsh P.P, Whelan C. (1999), Loss-Leading and Price Intervention in Multi-Product Retailing: Welfare Outcomes in a Second Best World, The International Review of Law and Economics, Vol.19, No.3.