Chapter 11 - Tools and Resources for Anti

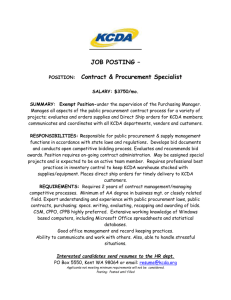

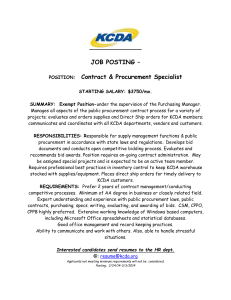

advertisement