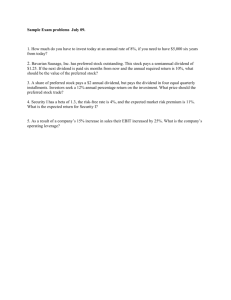

CHAPTER 19: Dividend Policy

advertisement

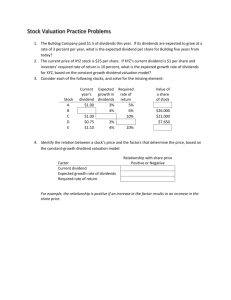

CHAPTER 19: Dividend Policy Topics: • • • • • • • 19.1 Basics 19.2 Price behavior around ex-dividend date (problem 11) 19.3 An illustration that dividend policy is irrelevant 19.5 Dividend policy is relevant with taxes 19.4 Share dividend and repurchases 19.7&9 What we know about dividend policy 19.8 Clientele effect 1 The FIRST PRINCIPLES • Invest in projects that yield a return greater than the minimum acceptable hurdle rate. • Choose a financing mix that minimizes the hurdle rate and matches the assets being financed. • If there are not enough investments that earn the hurdle rate, return the cash to the owners of the firm. – The form of returns - dividends and stock buybacks - will depend upon the stockholders’ characteristics. • Objective: Maximize the Value of the Firm 2 Introduction Why do corporations pay dividends? Why do investors pay attention to dividends? Perhaps the answers to these questions are obvious. Perhaps dividends represent the return to the investor who put his money at risk in the corporation. Perhaps corporations pay dividends to reward existing shareholders and to encourage others to buy new issues of common stock at high prices. Perhaps investors pay attention to dividends because only through dividends or the prospect of dividends do they receive a return on their investment or the chance to sell their shares at a higher price in the future. Or perhaps the answers are not so obvious. Perhaps a corporation that pays no dividends is demonstrating confidence that it has attractive investment opportunities that might be missed if it paid dividends. If it makes these investments, it may increase the value of its shares by more than the amount of the lost dividends. If that happens, its shareholders may be doubly better off. They end up with capital appreciation greater than the dividends they missed out on, and they find they are taxed at lower effective rates on capital appreciation than on dividends. In fact, I claim that the answers to these questions are not obvious at all. The harder we look at the dividend picture, the more it seems like a puzzle, with pieces that just don’t fit together. - F. Black, “The Dividend Puzzle”, Journal of Portfolio Management, Winter, 1976, pp. 5-8. 3 Principle 3 Illustrated: Microsoft Dividend • Just days into 2003, Microsoft predicted 2004 will be "daunting". – "Comparables [with 2003] will be daunting. It would be great to get some help from a better world wide economy, but the comparables for 2004 will be tough." (John Connors, CFO) • Microsoft announced its first dividend of 8 cents/share on a $43bn cash reserve – The dividend was payable March 7 to shareholders of record Feb. 21, 2003. 4 19.1 Basics • The two main ways that firms distribute cash to equity investors are dividends and share repurchases • Different Types of Dividends – Cash dividends: Usually paid four times a year in cash. – Stock dividends: e.g. 10% stock dividend • Distribution of stock. Does not affect the value of the firm or the wealth of the shareholder. • Increase shares outstanding – Stock split • Similar to a stock dividend. The NYSE requires share distributions of less than 25% to be treated as stock dividends. • Usually expressed in ratios. E.g. 2:1 means that investors get one new share for each share that they own (so the total number of shares outstanding doubles) • Share repurchases (buybacks) • The company buy back its own stock. • Can be either an open market repurchase (the firm buys on an exchange like any other investor) or a tender offer (the firm announces to all of its shareholders that it is willing to buy a fixed number of shares at a specified price) 5 Dividends Four dates associated with dividends • declaration date (1) – the day the dividend is announced • record date (2) – dividend is paid to the shareholders of record on this date • ex-dividend date (3) – the date on and after which the sellers of the stock, not the buyers, will receive the current dividend - two business days before the record date – prior to the stock going ex-dividend, it is said to be selling cum-dividend • payment date - cheque mailed or account credited (4) • the announcement, record and payment dates are set by the board of directors and the ex-dividend date is set by the stock exchanges • Time line: Time 6 Example: RBC dividend • Royal Bank of Canada (RY on TSX and NYSE) today declared a quarterly common share dividend of $0.50 per share, payable on November 24, 2008, to common shareholders of record on October 27 (Monday), 2008. • Q: If you are an investor – when do you get your dividend for the second quarter? – By which date do you have to buy the stock to have the third quarter dividend? – When is the ex-dividend date? Do you expect stock price to increase or decrease on the ex-dividend date? 7 19.2 Price Behavior around the Ex-Dividend Date • In a perfect world without taxes, the stock price will fall by the amount of the dividend on the ex-dividend date. • Taxes complicate things a bit. Empirically, the price drop is less than the dividend and occurs within the first few minutes of the ex-date. Illustration: • Let P0 = Original purchase price Pb= Price before the stock goes ex-dividend Pa=Price after the stock goes ex-dividend D = Dividends declared on stock Td, Tg = Taxes paid on dividend income and capital gains respectively Pb Pa Ex-div. day 8 Cash flows from selling around ex-dividend date • The cash flows from selling before the ex-dividend day are: Pb - (Pb – P0) Tg • The cash flows from selling just after the ex-dividend day arePa - (Pa – P0) Tg + D(1-Td) • Since the average investor should be indifferent between selling right before the ex-dividend day and selling right after the ex-dividend day Pb - (Pb – P0) Tg = Pa - (Pa – P0) Tg + D(1-Td) • Moving the variables around, we arrive at the following 9 Price change, Dividends, and Tax rates—Investor Perspective Pb Pa 1 Td D 1 Tg (1) If Td = Tg then Pb - Pa = ΔP = D (2) If Td > Tg then Pb - Pa = ΔP < D: price fall smaller than D. (3) If Td < Tg then Pb - Pa = ΔP > D: price fall greater than D. • Canadian scenario: – Td > Tg, ex-dividend date price fall smaller than dividend amount. 10 A dividend capture strategy with tax factors XYZ company is selling for $50 at close of trading May 3. On May 4, XYZ goes ex-dividend; the dividend amount is $1. The price drop (from past examination of the data) is only 90% of the dividend amount. The transactions needed by a tax-exempt university pension fund for the arbitrage are as follows: 1. (Buy or sell?) 1 million shares of XYZ stock cum-dividend at $50/share. 2. Wait till stock goes ex-dividend; (Buy or sell?) stock for _____ /share. 3. Collect dividend on stock. • Net profit = 11 Dividend Policy under Perfect Capital Markets • Dividend policy: How should I set up my dividend to maximize stockholder value (share price)? – Dividend policy (focus is on cash dividend): • How much? ($, payout ratio, or yield? Affordability.) • When? • As with capital structure, we start with perfect capital markets (Markets are perfect and frictionless, and no taxes) – Also assume that: • Investments and cash flows are known with perfect certainty. • The investment policy is fixed and is not affected by changes in dividend policy. • MM Prop. under PCM: Investors are indifferent to dividend policy 12 The benchmark case: an illustration of the irrelevance of dividend policy York Corporation, an all-equity firm. The current financial manager knows at the present date (t = 0) that the firm will dissolve in 2 years (t = 2). At t = 0 the manager is able to forecast cash flows with perfect certainty so she knows that each year (years 1 & 2) will generate $10,000. The return on equity is 10% and there are currently 100 shares outstanding. The firm currently has no positive NPV projects available. • The Question: How much can it pay in dividends (in years 1 & 2) ? 13 Cont’d: Irrelevance of dividend policy Dividend policy alternative 1: Set dividends equal to current cash flow • In this case, the aggregate dividend is $10,000 per period, (per share = $100), so the value of the firm is: ($17,355.37) And the value per share is: ($173.55) 14 Cont’d Alternative 2: Set initial dividend greater than cash flow • If the firm decides to issue a $110 per share dividend at t = 1 then the total amount of cash need is $11,000. Since this exceeds the cash on hand for the year, the funds must be raised by selling stocks or bonds. Suppose the firm issues $1000 of stock to finance the dividend. • The new stockholder require a 10% rate of return such that their payoff at t = 2 will be $1,100. (1) How many shares did the new investors get for their $1,000? (1) What’s the share price for old shareholders? (173.55) 15 Cont’d Cashflow to old S/H Date 1 Date 2 Aggregate dividend to old S/H Dividend per share (1)Shares to new shareholders: (2) Price of stock to old s/h: Verify: Price of new issue at date 1: return: 16 Cont’d: Implications of this example • The time patterns of dividends should not matter as long as the investor is fairly compensated through the return on equity. – The PV of the stock in both scenarios is the same. • Investors would not pay more for the firm if they can either replicate or undo the dividend decision—called homemade dividends • If this argument reminds you of homemade leverage in the context of capital structure – the proposition that in perfect capital markets the value of a firm value is independent of its dividend policy was first shown by Modigliani and Miller (MM) 17 Homemade Dividends • For example, assume that the firm will pay $110 at t = 1 and $89 at t = 2. • If Investor A wants $100 in both t = 1 and t = 2. Can she undo the firm's decision to achieve her desired consumption? – She can simply reinvest the extra in the company's stock and receive the following at the end of t = 2: • from dividend of the firm • from her investment since the fair return is 10%. • Total is 100. 18 Homemade dividends cont’d • Alternatively, if the firm decides to pay $100 in both t=1 and t=2 and Investor B desires consumption of $110 in t = 1 and $89 in t = 2, – She can simply sell _______ worth of shares at t = 1 and therefore, be out _________ worth of dividends at t = 2. • Total wealth unchanged. • Another way to put homemade dividend: Dividend policy has no impact on the value of a firm because investors can create whatever income stream they prefer by using homemade dividends 19 Summary: Perfect Capital Markets • Given the MM assumptions of perfect capital markets, then: – Dividend policy is irrelevant • given the firm’s investment decisions, how the firm decides to pay dividends doesn’t matter since shareholders can achieve any desired income pattern with homemade dividends – Dividends are relevant • shareholders prefer high dividends to low dividends if this higher dividend level can be maintained over time • Main implication: if dividend policy does matter, it is because of market imperfections such as taxes, transactions costs, asymmetric information, etc. 20 A review example: Homemade Dividends Problem: The MM Company earns a perpetual operating income of $2.5 million per year which it pays as dividends on its 200,000 outstanding shares. MM is all-equity financed with a required rate of return of 10%. The VP of Finance feels that shareholders would benefit if dividends were increased by $7.50 next year, but only next year. Assume that issuing stock is the only financing alternative. (a) What is the stock price under the current dividend policy? (b) How many new shares must MM issue in order to finance the new policy? (c) Mr. Jones owns 1,000 shares and prefers the current dividend policy? How can he achieve it if the firm switches to the new policy? 21 19.5 Effect of Taxes • Do TAXES matter for dividends? As with capital structure, Yes! – Firms should maximize shareholder AFTER-TAX value. • Individual taxes on capital gains are generally smaller than ordinary income – What’s more, capital gains are taxed at a lower rate since they are deferrable. • If you don’t sell, there is no capital gains. • (Annualized) Effective capital gain tax is in fact low. • For a long-term investor, we can assume the effective capital gains tax is close to zero. 22 Taxes matter—Perspective of Firm • From the firm perspective – If there is +NPV project, then firm should generally do those projects. – After +NPV projects, if there’s extra cash, if the firm retains earnings and reinvest on financial assets, it (generally) has to pay corporate taxes. – In the end, it has to distribute dividend. At the time of dividend distribution, investors paid taxes. – The choice is then between: (1) retain earnings now and distribute dividend later, and (2) distribute dividend and let investors invest themselves. 23 EXAMPLE The Regional Electric Company has $1000 of extra cash (after tax). It can retain the cash and invest it in T-bills yielding 10% or it can pay the cash to shareholders as a dividend. (Assume T-bills pay interest annually.) Shareholders can also put the money in T-bills with the same yield. Both firm and investor reinvest their interest income on T-bill. The corporate tax rate is 34% and the individual (universal) rate is 28% for both dividends and interest income. What is the amount of cash that investors will have after 5 years under each of the following scenarios: a. Pay dividends b. Retain the cash for investment in the firm 24 Solution a. Pay dividends. Shareholders receive in 5 years: ($1019.30) b. Retain the cash for investment in the firm. The company retains the cash and invests in T-bills and pays out the proceeds 5 years from now. (Individuals pay the taxes at the end) Shareholders receive in 5 years: ($991.188) 25 Conclusion on Taxes • Let ri = return investors can earn with dividend. rc = return corporations can earn with dividend. Ti = individuals tax rate, Tc = Corporations tax rate • General Rule for Dividend Payment when there is no +NPV project: (1 - Ti)(ri) (1 - Tc)(rc) a. If , pay dividends b. If , retain earnings • Holding the return on assets constant, a firm that has a higher tax rate than the individual will be better off paying out dividends rather than retaining them. – In other words, lower personal tax rates (compared to corporate tax rates) give firms an incentive to increase payouts – And vice versa. In the previous example, 26 Irrelevance of Stock Splits and Stock Dividends • XYZ Inc. is an all-equity firm with 2 million shares outstanding that are trading at $15 per share. The company declares a 50% stock dividend. How many shares will be outstanding after the stock dividend is paid? After the stock dividend what is the new price per share and the new value of the firm? • a 50% stock dividend will increase the number of shares by 50% to 2 × 1.5 = 3 million (in fact, this is really a 3:2 split) • the value of the firm was 2 × $15 = $30 million, which is unchanged after the dividend • the price per share is $30,000,000 ÷ 3,000,000 = $10 • No effect on any investor’s wealth. E.g., for an investor who owned 50 shares – total value before the stock dividend: 50 × $15 = $750 – total value after: 75 × $10 = $750 27 Stock repurchases • Instead of declaring cash dividends, firms can get rid of excess cash by buying shares of their own stock – • Potential tax advantages of stock buybacks vs. dividends: 1. 2. 3. • In the U.S., the amount of cash distributed by a share repurcahse in recent years has been roughly equivalent to the amount paid out as dividends If you choose to let your shares be repurchased, you paid capital gains tax on your capital gains • The effective capital gain tax is low if you hold your shares long enough. If you prefer dividends, you paid dividend taxes. • Dividends are smooth; and multiple times a year • Effective dividend tax rate is higher. If you prefer to hold on to the shares in the event of repurchases, your wealth won’t be affected by taxes When tax avoidance is important, share repurchase is a potentially useful alternative to dividend policy. 28 Stock Repurchase versus Dividend: Tax comparison Consider a firm that wishes to distribute $100,000 to its shareholders. Assets A.Original balance sheet Liabilities & Equity Cash $150,000 Debt 0 Otherassets 850,000 Equity 1,000,000 Value of Firm 1,000,000 Value of Firm 1,000,000 Shares outstanding = 100,000 Price per share= $1,000,000/100,000 = $10 29 Stock Repurchase versus Dividend Assume that dividend tax rate is 20%. If they distribute the $100,000 as cash dividend, the balance sheet will look like this: Assets Liabilities & Equity B. After $1 per share cash dividend Cash Debt 0 Other assets Equity Value of Firm 900,000 Value of Firm 900,000 Shares outstanding = 100,000 Price per share = $900,000/100,000 = $9 Shareholder value per share: 30 Stock Repurchase versus Dividend If they distribute the $100,000 through a stock repurchase, the balance sheet will look like this: Assets Liabilities& Equity C. After stock repurchase Cash Debt 0 Other assets Equity Value of Firm 900,000 Value of Firm 900,000 Shares outstanding= 90,000 Price per share = $900,000 / 90,000 = $10 • Shareholder value per share (to existing shareholders): 10 • Assume that capital gains tax rate is zero. If the shareholder sells the share, the value is $10. • This example shows that tax consideration is important. Moreover, there are tax advantages in repurchase. 31 Real World Factors Affecting the Repurchase Decision • Besides taxes, what other potential advantages do share repurchases offer? – Flexibility: an increase in a dividend is often viewed as an ongoing commitment, whereas a repurchase is more of a one-time deal – Executive compensation: firms with lots of executive stock options are more likely to prefer repurchases, because • the share price will fall when dividends are paid out, reducing the value of the options • Offset to dilution: to counter the dilution that occurs when the options are exercised) – Repurchase as investment: managers may believe that their firm’s stock price is temporarily undervalued, and so buying back shares represents a good investment • Empirical evidence supports this—long term stock price performance of firms after a repurchase tends to be substantially better than that of non-repurchasers 32 Real World Factors in Favour of High Dividends • From a tax perspective, the higher effective tax rate on dividends compared to capital gains suggests that dividends should be reduced • Other considerations, however, indicate that dividends should be increased: – Desire for current income (the excess cashflow hypothesis): the homemade dividend argument in perfect markets ignores transaction costs, so investors who want income now may prefer to receive it directly rather than incurring costs of selling securities – agency costs of equity: conflict of interest between managers and shareholders. Paying out dividends reduces the problem • but repurchases would also accomplish this – Tax arbitrage: some people argue that investors may be able to avoid taxes on dividends (e.g. if you borrow money to invest, interest payments are tax deductible against investment income received) – Information signalling – Clientele effect 33 Information content and signalling • Empirical evidence shows that stock prices increase when firms announce an increase in their dividends and decrease when firms announce cuts in dividends or suspensions of dividend payments • Is this because a higher dividend is a good financial decision, or because it conveys favourable information to the market? • Some (e.g. Lintner) have argued that a firm’s earnings should be viewed as containing both permanent and temporary components, and that firms have long run dividend payout ratio targets that depend on the permanent component – management will use a dividend increase to signal its expectation of high future (permanent) earnings – changes in dividends will be smoother than changes in earnings 34 The Clientele Effect • Investors may form clienteles based upon their tax brackets. Clienteles for various dividend payout policies are likely to form in the following way: Group High Tax Bracket Individuals Low Tax Bracket Individuals Tax-Free Institutions Corporations Stock Zero to Low payout stocks Low-to-Medium payout Medium-to-high Payout Stocks High Payout Stocks Once the clienteles have been satisfied (e.g. if there are already enough firms paying high dividends to meet demand), a corporation is unlikely to create value by changing its dividend policy. 35 A clientele based explanation • Evidence: A study of 914 investors' portfolios was carried out to see if their portfolio positions were affected by their tax brackets. The study found that (a) Older investors were more likely to hold high dividend stocks and (b) Poorer investors tended to hold high dividend stocks 36 19.9 What We Know About Dividend Policy • Corporations “smooth” dividends. • Dividends follow earnings. • Stock buybacks are more popular after 1990s. 37 Measures of dividend policy • payout ratio: dividend/net earnings – EPS = 2, Dividend = 1 payout ratio = ½ = 50% • dividend yield: dividend/price – P = 4, annual dividend = 1 dividend yield = ¼ = 25% 38 Dividends are sticky 39 Earnings 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 1986 1985 1984 1983 1982 1981 1980 1979 1978 1977 1976 1975 1974 1973 1972 1971 1970 1969 1968 1967 1966 1965 1964 1963 1962 1961 1960 $ Dividends/ Earnings Dividends tend to follow earnings Figure 21.5: Div idends and Earnings at US Firms: 1960 - 1998 45.00 40.00 35.00 30.00 25.00 20.00 15.00 10.00 5.00 0.00 Year Dividends 40 More firms are buying stocks buy, rather than paying dividends 41 Dividend payout ratio in the United States: Jan. 2004 Number of dividend paying firms = 2110 Number of non-dividend paying firms = 4647 Dividend Payout Ratio 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 0-5% 10-15% 20-25% 30-35% 40-45% 50-55% 60-65% 70-75% 80-85% 90-95% >100% 42 Dividend yield in the United States: Jan. 2004 Number of non-dividend paying firms Dividend Yields 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 00.25% 0.50.75% 11.25% 1.51.75% 22.25% 2.52.75% 33.25% 3.53.75% 44.25% 4.54.75 >5% 43 Summary: Determinants of Dividend Policy • Investment Opportunities – More investment opportunities Lower Dividends • Stability in earnings: – More stable earnings Higher Dividends • Alternative sources of capital – More alternative sources Higher Dividends • Constraints – More constraints imposed by bondholders and lenders Lower Dividends • Signaling Incentives – supply information to financial markets as signal higher dividend if needs are high • Stockholder characteristics – Older, poorer stockholders Higher dividends • Corporate control – More desire for control by current shareholders avoiding issuing new securities lower dividend • Agency cost of equity – Higher cost higher dividend 44 Summary cont’d • After accepting all positive NPV projects, firms should payout dividends out of extra cash if the corporate tax rate > the individual tax rate. • The debate on which dividend policy increases the value of the firm is still unresolved from a tax viewpoint. We have no precise answer on the optimal dividend policy. • Firms should not cut back on positive NPV projects to pay a dividend, with or without personal taxes and should avoid issuing stock to pay a dividend in a world with personal taxes. 45 Review Questions 1. Over the last 30 years, the proportion of the market value of stocks held by pension funds has increased substantially. Holding everything else constant, what implication does this trend have for dividend policy in the aggregate and why? 46 2. Suppose that a firm has $1,000,000 that it can either pay out as a special dividend or retain for internal investment. If the firm retains the money, it can earn an after-tax return of 6% per year over the next five years. This return will be distributed to shareholders as an additional dividend over the next five years. After the five-year period is up, the $1,000,000 will be paid out as a special dividend. 5 year Treasury bonds are currently yielding 7%. You own 10% of the shares and face a 40% tax rate on both interest and dividend income. Would you prefer the firm to pay out the $1,000,000 today? 47 • Assigned Problems: # 19.1, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 18, 20, 24 48 49 Additional page: Readings—Use your own judgements! Dividends: Do People Pay Attention? As an indication of the attention given to the topic of dividends, we present a few excerpts drawn from the popular financial press. • Dividend changes historically are a lagging indication of corporate profitability and at the same time a sign that corporate boards have confidence in the future. Because dividend reductions are seen as a very bad sign, companies hate to raise payouts to an unsustainable level. (The New York Times, January 3, 1997, Section D, p.4) • Corporate managers around the world are clearly attuned to the tax consequences of repurchases as compared with dividends. Consider the case of Reuters Holdings, the London-based media giant, which suspended its move to effectively buy back 5% of its shares in October 1996, after the British government announced it would toughen tax laws on such deals. ....Instead of using the special dividend structure, ...”Reuters might consider doubling up its regular dividend.” (The Wall Street Journal, October 9, 1996, p. A18) • One big disadvantage of larger dividends is that they erode a company’s cash cushion for recessions. All of the Big Three auto makers quickly burned through their cash reserves during the last recession five years ago, and they have been determined not to repeat the experience. 50 Larger dividends and lower cash reserves also mean slightly less assurance to bondholders that a company will be able to repay them in hard times. As a result, companies with generous dividends tend to have slightly lower credit ratings, which raise their borrowing costs. (The New York Times, May 17, 1996, Section D, p.1) • Changes in dividend policy tend to coincide with the release of other important news concerning the company. Some firms, like Microsoft and Intel, pay no dividend because they can generate higher returns for shareholders investing their profits back in the company. Interestingly, there is evidence that investors typically underestimate the full importance of fluctuating dividends. In a number of recent studies, economists were not surprised to find that the share prices of firms that cut dividends underperformed firms that increased dividends in the 12month period preceding the announcement of the cut. (The Detroit News, August 54, 1996, p. F2) • Financial theory says that share splits, buybacks, and dividend cuts should not affect share prices, but they do because investors believe that managers are trying to convey information with these actions....a dividend cut suggests that insiders expect profits to languish for years. These moves have gained their signaling power partly because investors do not trust managers to tell them the truth. (The Economist, August 15, 1992, p.14) 51