1.1 MB - Financial System Inquiry

advertisement

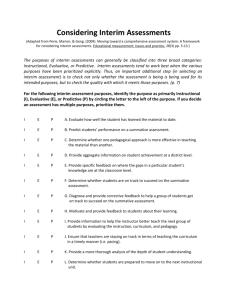

Submission in response to the Interim Report of the Financial System Inquiry 26 August 2014 57 Carrington Road Marrickville NSW 2204 Phone 02 9577 3333 Fax 02 9577 3377 Email ausconsumer@choice.com.au www.choice.com.au The Australian Consumers’ Association is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee. ABN 72 000 281 925 ACN 000 281 925 About CHOICE Set up by consumers for consumers, CHOICE is the consumer advocate that provides Australians with information and advice, free from commercial bias. By mobilising Australia’s largest and loudest consumer movement, CHOICE fights to hold industry and government accountable and achieve real change on the issues that matter most. To find out more about CHOICE’s campaign work visit www.choice.com.au/campaigns and to support our campaigns, sign up at www.choice.com.au/campaignsupporter CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 2 Contents Contents ......................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary: ........................................................................... 4 Summary of Recommendations .............................................................. 5 1. Disclosure .................................................................................. 6 2. Financial Advice .......................................................................... 10 3. Other issues ............................................................................... 17 3.1. Competition in the Banking Sector 17 3.2. Payment systems 21 3.3. Post-GFC regulatory response 23 3.4. Macro prudential tool kits 24 3.5. Compensation arrangements 24 3.6. Insurance 24 3.7. Regulatory Architecture 25 3.8. Emerging Trends: Open Data 26 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 3 Executive Summary: CHOICE appreciates the opportunity to provide the following comments to the Financial System Inquiry. CHOICE agrees with the broad conclusion that the financial system architecture is largely as it should be and has supported Australians well over the past 15 years. The challenge is how to use and refine this architecture to achieve better consumer outcomes. CHOICE was encouraged by the Inquiry’s insightful decision to move beyond the Wallis framework and address issues with disclosure and the current regulatory scheme. CHOICE has recommended giving ASIC additional powers to conduct market studies, to accept Super Complaints about systemic issues and to take stronger action when necessary through product intervention rules. Accompanying this, ASIC must be well funded to undertake these vital regulatory functions. Consumers should also be protected through the removal of conflicts of interest. CHOICE has put forward a series of recommendations to improve financial advice. Underpinning these recommendations are two guiding principles: that advisers all conflicts of interest caused by fees, commissions and remuneration should be removed and that advice must always be in the best interests of consumers. Applied correctly, these principles will allow consumers to trust advice services and use them to navigate their way through the complexity of the financial system. We also urge the Inquiry to re-examine the case for promoting demand-side competition in Australia’s banking sector, making it easier for consumers to act on their preferences and find banking products and services that best meet their needs. One solution to address competition issues is to provide consumers with access to their own data and with the tools to understand their usage. The submission puts forward a proposal to develop an open data program similar to the midata scheme in the United Kingdom. This would provide consumers with a better understanding of their own consumption patterns and allow personalised product comparison for complex products. CHOICE has been unable to respond to all questions in the Interim Report given the breadth of issues covered and timeframe in which to respond. We have chosen to focus on issues in the report where we are able to make the most valuable contribution based on our resources and expertise. For sections of the Interim Report that we have not been able to address in detail, CHOICE endorses the concerns identified and the recommendations made in the submissions of the Superannuation Consumers’ Centre, Consumer Action Law Centre and Financial Rights Legal Centre. One area of financial services that we feel suffers from the lack of a well-resourced consumer perspective is superannuation. CHOICE therefore asks that the Inquiry recognise the importance of formal consumer participation in discussions about the future of the financial system by calling for Government funding for a superannuation and retirement consumer centre. An independent, superannuation-focused consumer organisation would ensure that consumers are well-represented in major reviews, assist regulators in prioritising action and advocate for quality default products across the superannuation and retirement systems. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 4 Summary of Recommendations The Government provides on-going support for consumer advocacy through funding a Superannuation Consumers’ Centre. Recommendation 1: ASIC is granted new temporary and permanent product intervention powers. Recommendation 2: Recommendation 3: ASIC is granted a market studies power. Recommendation 4: ASIC is granted the ability to accept super complaints. The Inquiry considers how a prohibition on unfair trading could assist in improving consumer outcomes. Recommendation 5: All fees, commissions and remuneration linked to personal and general advice that create a risk of conflict of interest are banned. Recommendation 6: Advisers are required to act in their clients best interests at all times with no exceptions. Recommendation 7: The Inquiry calls for a thorough investigation and review into mortgage broker services and any resulting consumer detriment. Recommendation 8: That the Inquiry reassesses the conclusion that Australia’s banking sector is competitive. Recommendation 9: A regulator is given explicit legal power to enforce the RBA ruling that limits surcharges to the reasonable cost of acceptance. Recommendation 10: The RBA regularly assesses and defines a reasonable surcharge rate for different card types based on business size and releases this assessment alongside of average merchant service fee data. Recommendation 11: That large businesses be required to report to the RBA on the total amount collected annually through surcharges to increase transparency. Recommendation 12: That a statutory compensation scheme modelled on the Financial Services Compensation Scheme in the United Kingdom is established to address unpaid determinations. Recommendation 13: The Government initiates a review of the regulation of insurance with a focus on future proofing insurance in the context of the challenges of climate change, improving consumer outcomes and competition. Recommendation 14: Government works with industry, consumer groups and privacy and security experts to develop an open data scheme. As a secondary goal this group should consider opportunities for releasing de-identified data for public use. Recommendation 15: CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 5 1. Disclosure Recommendations ASIC is granted new temporary and permanent product intervention powers. ASIC is granted a market studies power. ASIC is granted the ability to accept super complaints. The Inquiry considers how a prohibition on unfair trading could assist in improving consumer outcomes. CHOICE welcomes the Interim Report’s widely accepted observations on the limitations of financial disclosure as a consumer protection measure. The case for adopting a new approach to financial consumer protection has been well prosecuted in the evidence presented to the inquiry. The challenge, as David Murray noted is to “develop a viable alternative approach that is not simply more detailed rules”1. The FSI needs to bring a new guiding vision to underpin the interplay between financial product and service regulation and consumer needs, behaviours and values. Improving Disclosure ASIC has established a good track record of working with stakeholders to innovate in financial product and service disclosure. While the Interim Report notes that it is still too soon to assess the impact of these innovations, there are constructive examples of ASIC working to improve disclosure in superannuation, managed investments, consumer credit and mortgage broking. The FSI should firmly register its support for continuous improvement and innovation in the communication of financial product (and service) information disclosure. Any barriers to achieving this ambition utilising existing regulatory instruments should be clearly identified by the committee. The Interim Report suggests one way to improve disclosure could be a new obligation on product issuers to disclose the class of consumer for whom the product is suitable. This may assist some consumers and advisers and should be considered by ASIC. However, as noted above, the FSI should not just create more detailed rules on disclosure. CHOICE supports ASIC’s on-going efforts to continually improve disclosure but the Inquiry must look beyond reforms to disclosure in order to improve consumer outcomes. Temporary and Permanent Product Intervention Rules On 5 August 2014 the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) used its temporary product intervention rules for the first time to restrict the sale to retail customers of contingent convertible instruments (commonly known as CoCos).2 The restriction will commence on 1 Speech to the National Press Club, 15 July 2014 by Mr David Murray AO, Chairman of the Financial System Inquiry. Financial Conduct Authority, 5 August 2014, Restrictions in relation to the retail distribution of contingent convertible instruments: http://www.fca.org.uk/news/restrictions-in-relation-to-the-retail-distribution-ofcontingent-convertible-instruments 1 2 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 6 October 2014 and is in place until 1 October 2015, during which time the FCA will undertake a formal consultation process on permanent rules to commence from 1 October 2015. CoCos are hybrid capital securities that absorb losses when the capital of the issuer falls below a certain level. The FCA has taken this step because it deems that CoCos are risky and highly complex products that “pose particular risks of inappropriate distribution to ordinary retail customers”3. A recent statement from the European Securities and Markets Authority (31 July 2014) supports this position. It identified extensive risks associated with the asset class. 4 Specifically, the ESMA noted its concern that “it is unclear as to whether investors fully consider the risks of CoCos and correctly factor those risks into consideration prior to investing in these instruments.” 5 Hybrid securities have recently attracted the attention of the Australian regulator too. In 2013 ASIC published a report into hybrid securities, including bank hybrids with loss absorption events similar to CoCos.6 It found a burgeoning market of highly complex and risky instruments marketed primarily to retail investors. It estimates the size of the market to be 75,000 current direct investors of which 67 per cent are SMSFs. In the 18 months to July 2013, around $18 billion was raised through ASX-listed hybrid securities. The report finds that, “The lack of institutional interest, which continues to a lesser degree in the secondary market, is often attributed to hybrid securities falling outside the terms of traditional fixed income mandates. One alternate explanation is that institutional investors consider the credit and other risks of hybrid securities are not adequately priced, which if true suggests that retail investors may not be fully compensated for the risks they are assuming."7 ASIC also reports anecdotal findings that not-for-profit organisations and local councils are being advised to use hybrid securities to form part of their fixed income investment portfolios.8 These products have all the hallmarks of misfortune waiting to happen. They are issued by wellknown brands so are attractive to retail investors but are so complex that institutional investors are wary of how to price them. Despite this, it is concerning that ASIC found 85 per cent of retail investors in hybrid securities rated their overall understanding of these securities as ‘average’ or better.9 Along with ESMA and the FCA, ASIC has profound concerns about the new class of hybrid securities issued by prominent corporations, notably banks. The FCA has acted to remove products from the shelf while it works with the product manufacturers in a defined process to 3 Ibid. European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), 31 July 2014, Potential risks associated with investing in contingent convertible instruments: http://www.esma.europa.eu/content/Potential-Risks-Associated-InvestingContingent-Convertible-Instruments 5 Ibid. 6 ASIC, August 2013, Report 365 Hybrid Securities: https://www.asic.gov.au/asic/pdflib.nsf/LookupByFileName/rep365-published-20-August-2013.pdf/$file/rep365published-20-August-2013.pdf 7 Ibid p 11. 8 Ibid p 11. 9 Ibid p 32. 4 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 7 ensure the financial products sold to retail investors are fit for consumption. In the absence of temporary or permanent product intervention rules, ASIC is more limited in the actions it can take. ASIC is left falling back on the old mantra of disclose, educate and seek advice. It has published comprehensive information on MoneySmart.gov.au and sent its commissioners out in the media with strong warnings to investors. The 2013 report outlines steps taken to improve disclosure. But disclosure, education and advice all suffer from general imperfections and, in this specific instance, the documented consumer behaviours make those strategies even less effective. Despite ASIC’s efforts, demand from Australian retail investors remains strong and pricing appears unaffected by risk warnings. Australian consumers would be better served if the regulatory settings recognised that there will be circumstances (such as those outlined above) where disclosure, education and access to advice alone will not deliver the desired consumer protection outcomes. CHOICE therefore supports the adoption of new temporary and permanent product intervention rules, similar to those adopted by the FCA. These rules could set financial consumer protection on a new trajectory that recognises real limits to disclosure and provides regulators with a tool that can respond to heightened concerns about financial products and services, just as the FCA has done with contingent convertible instruments in the UK market. Financial product design rules, such as rules concerning superannuation default funds, are currently an ad-hoc part of the regulatory landscape. Consumers would be better served by a clearly defined and systematic role for ASIC to impose rules on product manufacturers. Product intervention rules would give ASIC the ability to consult with the stakeholder community on a specified issue with the result that product manufacturers are required to build and sell their product according to consumer protection specifications. We envisage that product intervention could be used to specify default settings, simplify features and fees structure to address behavioural biases or restrict distribution channels. We imagine that these rules would be used relatively rarely but their mere existence would increase the power of ASIC to work with product providers in less formal ways, to reduce risks to consumers. Market studies, super complaints and unfair trading prohibition In submission to the Competition Policy Review, CHOICE called for the ACCC to be granted new powers to conduct market studies.10 There is value in considering a similar power for ASIC in relation to financial services. The ACCC argues that market studies could be used; i. ii. As a lead-in to enforcement action when anti-competitive behaviour is expected but the exact nature and source of the problem is unknown; To identify a systemic market failure and to better target a response; 10 CHOICE, 10 June 2014, Submission to Competition Policy Review Issues Paper: http://competitionpolicyreview.gov.au/files/2014/06/CHOICE.pdf p 46. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 8 iii. iv. v. To identify market problems where affected parties are disadvantaged and either have difficulty making a complaint to the ACCC or accessing the legal system to take private action; To address public interest or concern about markets not functioning in a competitive way. The market study could either confirm these concerns, and propose some solutions, or find them to be unfounded; and To fact-find to enhance the ACCC’s knowledge of a specific market or sector, particularly where a market is rapidly changing, and raises issues across the ACCC’s functions.11 The market study rule differs from current investigative activities by enabling the regulator to look at a financial service or product in a broader social, economic and legislative context. CHOICE has also called on the Competition Policy Review to consider super complaint provisions. Once again, we see an opportunity to establish the same provisions at ASIC. Super complaint mechanisms can be a useful companion tool to market studies and investigations powers, or can exist as a stand-alone mechanism. In the UK, super complaints confer a right on specified consumer and small business organisations to make a ‘super complaint’ to the relevant regulator, with the regulator being obliged to respond to that complaint within a specified period of time. In order to constitute a super complaint, a complaint must relate to widespread concern or conduct in a market and must meet other quite significant thresholds in relation to information provision. CHOICE also urges the Inquiry to consider how a prohibition on unfair trading could assist in achieving the stated goals of improving consumer outcomes. We encourage the Inquiry to revisit this proposal put forward by the Consumer Action Law Centre as part of its response to the observation that the current disclosure regime is not meeting consumer protection outcomes.12 11 ACCC, 25 June 2014, Reinvigorating Australia’s Competition Policy Australian Competition & Consumer Commission Submission to the Competition Policy Review: http://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/reinvigorating-australiascompetition-policy-accc-submission-to-harper-review p 138. 12 Consumer Action Law Centre, 20 June 2014, Submission to Financial System Inquiry: http://consumeraction.org.au/submission-financial-systems-inquiry-terms-of-reference/ CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 9 2. Financial Advice Recommendations: All fees, commissions and remuneration linked to personal and general advice that create a risk of conflict of interest are banned. Advisers are required to act in their clients best interests at all times with no exceptions. The Inquiry calls for a thorough investigation and review into mortgage broker services and any resulting consumer detriment. Ideally, all financial advisers should be trusted professionals who can assist consumers with complex financial dealings according to their client’s best interests. We are still a long way from this ideal. As recent Inquiries and numerous financial advice scandals have shown, too often financial advisers have placed their own interests first and used their relationship with clients to sell products that have been unsuitable. The result is that consumers have lost billions from misselling and conflicted financial advice.13 Conflicts of interest in the industry must be removed to ensure advisers, regardless of their employers, are able to make independent, trusted recommendations to their clients. While some steps have been taken in recent years to improve standards and remove conflicts, more work is required. As the Interim Report was released, further changes to the Future of Financial Advice (FoFA) protections were finalised through the Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014 (the Regulation). The Regulation reduces essential consumer protections and reintroduces certain types of conflicted payments that will influence the quality of advice consumers will receive.14 CHOICE suggests that the Inquiry uses the Regulation as a starting point in considering the adequacy of current protections and laws. Conflicted remuneration CHOICE agrees with the Interim Report’s conclusion that “the principle of consumers being able to access advice that helps them meet their financial needs is undermined by the existence of conflicted remuneration structures in financial advice.”15 Any incentive to sell a volume or type of product is an unacceptable conflict of interest for a financial adviser, yet many conflicts are legal and common practice. Asset-based fees are paid by a client to an adviser as a percentage of the total funds under advice. These fees were not dealt with by any iteration of the Future of Financial Advice reforms. Asset-based fees have many of the same market distorting features created by 13 Consumers have lost $5.7 billion in major financial scandals including losses from Opes Prime, Storm Financial, Timbercorp/Great Southern, Bridgecorp, Fincorp, Trio/Astarra, Westpoint and Commonwealth Financial Planning sourced from figures in ASIC, 2014, Submission to the Financial System Inquiry, pp 192-193 and Industry Super Australia, 2014, Exposure Draft: Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice Bill 2014, ISA Submission, pp 37-38. 14 For further information on the consumer impact of these changes CHOICE, 2014, Submission to Senate Committee on Economics Inquiry into Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2014. 15 FSI, Interim Report, 3-65. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 10 commissions, which have been recognised as inappropriate for advisers and largely, although not entirely, excised from the industry. CHOICE believes that asset-based fees should be banned as they encourage advisers to direct clients into certain types of investments. Asset-based fees are significantly less transparent than fixed fees and, in cases where an adviser accepts asset-based fees from long-term inactive clients, allow fee-for-no-service business models to thrive (where a client continues to pay a fee long after they have received advice). Fixed fees for advice, either hourly rates or lump sums, remove these failings, as demonstrated in the table below. Failing Level of Risk Commissions Asset-based fees Fixed fees Adviser incentivised to recommend sale of nonfinancial assets (like real estate) to invest in financial assets High High None Adviser incentivised to recommend gearing High High None Adviser biased against liquid/safe assets which pay low or no commissions High Moderate None Lack of transparency in total remuneration to the adviser High Moderate None Value of advice relative to the cost of the advice is difficult for client to determine High Moderate None Adviser incentivised to recommend inappropriate products with big commissions High None None CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 11 Other forms of conflicted payments have been reintroduced by the new Regulation. The Regulation allows certain types of conflicted remuneration including bonuses linked to sales targets for general advice. These changes will reinvigorate a sales-driven culture and encourage mis-selling, particularly by bank staff. While the Regulation and original FoFA reforms banned most commissions, some remain such as commissions for selling life insurance. Conflicted payments place the interests of the adviser into direct conflict with the interest of the client. CHOICE believes that financial advisers should be banned from accepting any commissions, trails and asset-based fees due to the influence these forms of payment have on the quality of advice. The Regulation also allows for even more situations where advisers can buy and sell ongoing commissions that were entered into before 1 July 2013. Most notably, advisers who collect commissions on superannuation products sold before 1 July 2014 will be able to continue to collect these commissions when their client retires, allowing a lifelong commission in certain cases. An alarming number of financial advice clients are unengaged and unlikely to realise that they are paying ongoing commissions.16 CHOICE believes that the extensive grandfathering introduced in the Regulations and the original FoFA reforms should be removed. Should this not occur, at a minimum advisers should be required to contact all existing clients, outline all current fees and commissions paid and provide a simple opportunity for clients to stop the commissions. Institutional conflicts and the importance of independence Looking beyond individual adviser remuneration structures, institutional structures greatly affect the quality and type of advice a consumer receives. The influence of institutional ownership has become more of a concern over time as the financial advice industry has consolidated.17 Research has consistently shown that advisers working for major institutions are more likely to recommend products from these institutions. The latest ASIC shadow shop of financial advice found “widespread replacement of existing financial products with ‘in-house’ products.”18 Roy Morgan Research found that from 2007 to 2011 the six largest institutionally owned advice groups had directed 73% of superannuation recommendations to their own products.19 As recent events at Commonwealth Financial Planning have shown, strong links to major institutions can exacerbate a sales-driven culture in financial advice. Any incentive, financial or cultural, to recommend a quantity or type of product changes the motivation of an adviser and reduces the likelihood of a consumer receiving trustworthy advice. CHOICE believes that links between advice (including general advice) and sales targets must be banned. CHOICE notes that the Interim Report considers whether general advice is properly labeled. The issue with general advice is not in its labeling but in the conflicts and structures that influence the quality and nature of general advice. Before changing the term, extensive testing must be 16 A survey of the top 20 financial services licensees found that 3.1 million or two thirds of clients were inactive; they were paying commissions and ongoing advice fees but not receiving any benefit. See ASIC (2011), Report 251: Review of financial advice industry practice, p 4. 17 FSI, Interim Report, 3-72. 18 ASIC (2012) Report 279 Shadow shopping study of retirement advice, p 45. 19 Roy Morgan Research 2011, Superannuation & wealth management in Australia, quoted in ibid p 45. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 12 conducted to determine if consumers first have any awareness of the term general advice and if there is a more meaningful phrase. Institutional links also raise issues with consumer understanding of adviser independence. A recent Roy Morgan study found that consumers are extremely confused by multi-branding of financial advice businesses. 55 per cent of clients of Financial Wisdom, owned by CBA, thought their adviser was independent. Similarly, 50 per cent of clients of Godfrey Pembroke (NAB), 48 per cent of clients of Charter FO (AMP) and 37 per cent of clients of RetireInvest (ANZ) perceived their adviser to be independent.20 Surprisingly, 13 per cent of ANZ, 20 per cent of St George and 14 per cent of Commonwealth clients perceived their advisers to be independent even though they clearly work for a major institution. This likely links to how advisers represent themselves and their services. Financial advisers often present as professionals that are able to guide consumers through difficult decisions and meet financial goals. Major institutions state that they offer the best and most effective advice, implying that the full range of products across the market and strategies beyond product recommendation are considered when this is, as can be seen in the research above, often not the case. Because of the greater likelihood of being steered into a particular product, there must be greater clarity for consumers regarding the differences between independent and aligned advisers. One option is for Australia to adopt the UK system of labeling advisers either restricted or independent. CHOICE believes that this move could greatly benefit consumers but in order to find the most meaningful term for Australian consumers, CHOICE would like to see independent consumer testing of any changes to the way in which advice is labeled. Advice in the best interests of consumers Consumers expect financial advisers to act in their best interests, just as they would expect of other professions providing advice-type services such as lawyers. Part of ensuring that consumers get the best possible advice is dealing with conflicts. Another important component is ensuring that advisers have a clear obligation to always act in their clients’ best interests. The Regulation made several amendments to the definition and scope of the best interests duty.21 These changes leave only a ‘tick- a-box’ checklist to assess if the best interests duty has been met. This test to meet the best interests duty contains no mention of protecting the client’s best interest. This is inadequate, especially when compared to requirements on other professions that simply require that a professional act in their client’s best interest. 22 Worryingly, an adviser is able to bypass the duty to act in their client’s best interest when scoping advice. The Regulation inserts a note that reads: “Nothing in section 961B of the Act prevents the provider and a client from agreeing the subject of the advice sought by the 20 Roy Morgan Research, August 2014, Confusion with Financial Planner Independence Continues: http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/5716-confusion-with-financial-planner-independence-201408040221 21 The Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014 removes the requirement for advisers to prove they meet the step outlined in 961B(2) of the Corporations Act 2001, specifically 961B(2)(g) is removed, leaving only six process based steps to meet the test. 22 For example, tax agents are simply required to “act lawfully in the best interests of your client.” See http://www.tpb.gov.au/TPB/Subsidiary_content/Reg_info_sheets/0296_Code_of_professional_conduct_information_s heet.aspx CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 13 client”23 An example is added to remove any doubt that an adviser is able to scale advice without considering the best interests of the client.24 Rather than addressing the information asymmetry in the client-adviser relationship, these changes allow the lack of knowledge a consumer has about finance to be exploited as the adviser is able to steer a consumer into scaled advice which is restricted by, for example, the type of provider, product or risk. CHOICE recognises that scaled advice can be a valuable and more affordable service for many consumers but an adviser must always act in a client’s best interest, with that duty applying from the moment they meet with a client. A consumer is unlikely to realise that an adviser will only act in their best interests at a certain point when receiving scaled advice. In addition, these changes legalise sales-driven strategies and one-size-fits-all approaches to advice by excluding the initial investigations stage of an advice relationship from the best interests duty. Other loopholes created by the Regulation allow advisers giving certain types of personal advice to meet a reduced best interests duty. Again, a consumer is unlikely to be aware of this restriction and the risk of mis-selling is high. For example, an adviser is now also able to place their own or their employer’s interests ahead of their clients’ when giving personal advice on basic banking, general insurance or any combination of these products. A reduced best interests duty is inappropriate for any type of personal advice. Affordability of advice CHOICE welcomes the discussion about affordability of advice for consumers but stresses that basic consumer protections should never be sacrificed to increase affordability of advice. CHOICE cautions the Inquiry against presenting scaled advice as an affordable and desirable option for consumers. The current application of the best interests duty to scaled advice, outlined above, makes seeking scaled advice riskier than getting holistic advice. Requiring that an adviser has to act in the best interests of their client at all times, not just after agreeing on the scope of advice, will greatly reduce the risk of mis-selling and make scaled advice more attractive to consumers. In recent times, there has been a focus on reducing regulatory compliance costs for advisers as a means to reduce costs for consumers. There are many other ways to reduce costs, for example increasing productivity, increasing competition within the industry to place pressure on prices or by increasing efficiency through reducing business and administrative costs. Financial advice that is genuinely in the best interests of a client can be useful however it is not ideal that all consumers be required to seek financial advice. Instead consumers need a financial system with strong product defaults, clear disclosure, a regulatory framework that adequately manages risk, restrictions on dangerous products and easy-to-access redress mechanisms when something goes wrong. If all consumers require financial advice then the financial system in Australia is too complex. 23 Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014 s 7.7A.2 (2), note one. See Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014 s 7.7A2 (4): “Example: A client approaches the provider intending to seek advice on a particular subject matter. As a result of discussion with the provider, the client decides to instead seek advice on a narrower subject matter. The obligations of Division 2 of Part 7.7A of the Act apply to the advice ultimately sought.” 24 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 14 Current estimates from Roy Morgan indicate that 42 per cent of Australians have sought financial advice.25 CHOICE considers this number to be reasonably high considering that many consumers may not need advice at this current point in their life, have simple affairs or that one member of a household may seek advice that will assist a whole family. Other reasons for not seeking financial advice such as a lack of trust in financial advisers are unfortunately well founded given the recent history of the industry and the current legislative and regulatory framework. Removing conflicts and increasing transparency across the system There are systemic issues with financial advice in Australia but it is important to consider how conflicts of interest and non-transparent practices affect the quality of services across the financial system. CHOICE strongly supports the five consumer outcomes outlined in the Interim Report.26 CHOICE is concerned that consumers do not have confidence or trust in other financial services and do not expect or receive fair treatment. A national survey conducted for CHOICE found that 27 percent of people trusted bank tellers, 23 per cent trusted financial advisers and only 12 percent trusted mortgage brokers.27 These results indicate a lack of trust across the financial system but the finding about trust in mortgage brokers is particularly concerning. As the Interim Report notes, “Vertical integration of mortgage broking may create conflicts of interest, which could hamper competition.”28 CHOICE would add that conflicts of interest will also reduce quality of recommendations and service for consumers. The mortgage broking industry relies heavily on commission-based remuneration and as a result there is a high risk of conflicted remuneration influencing what a mortgage broker arranges for a consumer. Further work is required to fully explore the impact of mortgage brokers’ remuneration and institutional arrangements on the services they offer. National regulations for mortgage brokers were introduced relatively recently after a series of inquiries explored concerns with state based regimes.29 It is an appropriate time to conduct a thorough review into how these arrangements are working for consumers and if more extensive rules about quality of recommendations and disclosure are required. Other consumer protections required Opt-in and annual statements: It is vital that consumers are able to easily extract themselves from on going fee arrangements. Should a consumer choose to receive ongoing advice, advisers 25 FSI, Interim Report, 3-70. FSI, Interim Report, 3-50. 27 Results of 2014 CHOICE Consumer Pulse Survey, available at: www.choice.com.au/media-and-news/consumernews/news/choice-cost-of-living-report-highlights-tough-times-for-many.aspx 28 FSI, Interim Report, 2-21. 29 House Standing Committee on Economics, Finance and Public Administration, 2007, Inquiry into Home Lending Practices and Processes, http://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=efpa/bankle nding/report.htm 5.30. 26 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 15 must be completely transparent about what consumers are paying and what services they are receiving. The Regulation removes the requirement that an adviser must contact clients to have them opt in to ongoing advice every two years. This requirement was designed to stop people paying for advice they no longer needed. Opt-in would have assisted many consumers but particularly those paying asset-based fees. In addition, fee disclosure statements are no longer required for clients who entered into arrangements prior to 1 July 2013. Both of these changes remove practical consumer protections that would have increased transparency of ongoing fees and should be reinstated. Education standards: CHOICE supports raising minimum education and competency standards for all financial advisers. Recognising that existing advisers come from a range of educational backgrounds, CHOICE’s preference is for the establishment of a national exam with education and training requirements to be phased in over time. CHOICE also supports calls for competency standards to be raised for advisers giving advice on complex products, including SMSFs. However, this change cannot address industry issues alone. Increasing qualification standards without addressing structural conflicts will only lead to better educated financial advisers taking advantage of consumers. Introduction of an enhanced public register of financial advisers: CHOICE supports the introduction of a public register of financial advisers. CHOICE has participated in the working group developing the first iteration of this register and looks forward to its launch. The register will address some transparency issues within the industry and allow ASIC to track disreputable advisers. Over time CHOICE expects to see additional fields added to the register, increasing its usefulness to consumers. Additional banning powers for ASIC: CHOICE supports the proposal to enhance ASIC’s power to ban individuals from managing a financial services business. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 16 3. Other issues 3.1. Competition in the Banking Sector Recommendation: That the Inquiry reassesses the conclusion that Australia’s banking sector is competitive. CHOICE notes the Inquiry’s interim assessment that Australia’s “banking sector is competitive, reflecting a number of indicators.”30 While we appreciate the Inquiry has likely settled its view on the broad question of competition, it is useful to examine the indicators behind this assessment. In doing so, we urge the Inquiry to re-examine the case for promoting demand-side competition in Australia’s banking sector, making it easier for consumers to act on their preferences and find banking products and services that best meet their needs. In this section, we will examine each of the indicators cited in the Interim Report – net interest margins, returns on equity, customer satisfaction, product choice and bank fees income – and offer a view on whether they provide evidence of a competitive retail banking sector. Net interest margins: the Interim Report suggests these are “around historic lows and mid-range by world standards”, and references Reserve Bank data that traces the Net Interest Margins of the major banks since the late 1980s.3132 Obviously much has changed since the late 1980s – for example, Australia’s largest retail bank has transitioned from government to private ownership (1991-1996), the Wallis Inquiry has reported (1996-1997), and we have seen substantial consolidation in the sector following the Global Financial Crisis (2008-2009). While not taking issue with the RBA’s analysis, if we are seeking to assess how effective competition is in Australia’s retail banking sector at present, we believe it is useful to assess more recent data. As CHOICE observed in our initial submission to the FSI, the interest rate margin of the banks’ standard variable home loan over the Reserve Bank’s official cash rate target trended sharply down over the second half of the 1990s, levelling out at around 175 basis points. This margin compression is likely attributable to various factors, one of which is increased competition in the mortgage lending market. This low margin was sustained for an extended period, until late 2007, coinciding with the onset of the GFC. The margin has risen back to 345 basis points, where it has remained since December 2012, despite public statements from major banks as far back as 2011 that consumers could expect ‘out-of-cycle’ interest rate cuts in the months ahead.33 30 FSI, Interim Report, 2-7. FSI, Interim Report , 2-7. 32 Reserve Bank of Australia, March 2014, Submission to the Financial System Inquiry, p 27. 33 For example, see News.com.au, 8 March 2011 ‘Westpac bank's CEO Gail Kelly promises to pass on savings as rate cut’, accessible at http://www.news.com.au/finance/business/westpac-banks-ceo-gail-kelly-promises-to-pass-onsavings-as-rate-cut/story-e6frfkur-1226017435311 31 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 17 Standard variable home loan interest rate margin over official cash rate Percentage point difference 4.5 4.0 Standard variable 3.5 Discounted variable 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 Feb-94 Feb-98 Feb-02 Feb-06 Feb-10 Feb-14 Source: RBA data Analysis of the margin between credit card interest rates and the official cash rate shows a similar trend. The interest rate margin on a standard credit card gradually drifted up to around 11.25 percentage points in late 2001/early 2002. A period of stability then followed, through to around mid-2007 when the up-trend resumed. The margin increased sharply in the second half of 2008, rising from 12.25 percentage points in June to 14.70 percentage points in December. Following another period of stability where the margin remained at around 15.00 percentage points (April 2009 – October 2011), the margin has now widened to above 17 percentage points. Credit card interest rate margin over official cash rate 18 Percentage point difference 16 14 Standard Low rate 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Feb-94 Feb-98 Feb-02 Feb-06 Feb-10 Feb-14 Source: RBA data CHOICE believes that this analysis of Net Interest Margins during recent and relevant market conditions – that is, in the years immediately prior to and following the Global Financial Crisis does not support the view that there is effective competition in Australia’s retail banking sector. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 18 Returns on equity: the Interim Report references the RBA’s observation that the major banks’ returns on equity “are comparable to those achieved by other large Australian companies, as well as by major foreign banks before the GFC.”34 Independent analysis has consistently identified Australia’s major banks as among the most profitable in the world.35 While there are certainly a number of large Australian companies whose rates of return are similar to or larger than Australia’s major banks, most operate in an environment where a substantial weight of their risk is not borne by the community in the form of explicit and implicit guarantees. For example, most ASX 200 companies with substantial rates of return, such as carsales.com.au and Ainsworth Gaming do not fit the definition of ‘too big to fail’.36 Any assessment of Australia’s major banks’ returns on equity as an indicator of competition should compare like with like; that is, it should account for the banks’ privileged position in our economy, and the possibility that their profits are to some extent the result of enjoying oligopoly rents. Customer satisfaction and product choice: The Interim Report observes that customer satisfaction with the major banks has increased steadily “and is now at record highs.”37 CHOICE provided evidence in its initial submission that Australia’s big four banks are consistently ranked below smaller institutions in terms of product satisfaction across all major categories.38 We would question whether a genuinely competitive banking sector is one where the providers with the lowest relative customer satisfaction enjoy the overwhelmingly largest market share. This nationally representative research also found that 58 per cent of those surveyed agree that the Australian banking sector lacks competition on the services and offerings provided to consumers.39 It is also worth noting that Australian mortgage holders are enjoying a sustained period of very low interest rates, and there has been no movement in the RBA cash rate for more than 12 months. Consumer sentiment in relation to the major banks tends to be sensitive to interest rate pricing decisions, and these generally follow movements in the RBA cash rate.40 In this context, it is not surprising that current levels of customer satisfaction are high. 34 FSI, Interim Report, 2-7. Bank for International Settlements, 29 June 2014, 84th BIS Annual Report: http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2014e.htm p 107. 36 See Polites, Harrison, 3 July 2014, ‘Australia’s big four banks are not as profitable as we think they are’, Business Spectator, accessible at http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2014/7/3/financial-services/australias-bigfour-banks-arent-profitable-we-think-they-are 37 FSI, Interim Report, 2-7. 38 CHOICE, July 2014, Financial System Inquiry, p 11. 39 Ibid, p 11. 40 For example, see News.com.au, 1 May 2014, Labor and Coalition demand banks pass on rate cut: http://www.news.com.au/finance/economy/liberal-and-labour-demand-banks-pass-on-rate-cut/story-e6frfmn01226343869383 35 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 19 Consumer satisfaction with their financial institution (Respondents indicating they were “very satisfied”) 60% Big 4 50% Other 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Transaction account Home loan Credit card Savings account Source: CHOICE 2014 survey data The Interim Report also notes that the sheer number of products and providers in the market is an indicator of competition. CHOICE believes a more appropriate indicator would be not simply the quantity of options, but the degree to which they are genuinely differentiated, and offer consumers high quality, competitive products that meet their needs. Similarly, it is not simply a question of the number of product providers, but the extent to which they compete and innovate to meet consumers’ preferences, and indeed the extent to which they are rewarded for this through market share. Banking fee income: the Interim Report notes that “[f]ees paid by households have declined in absolute terms since 2010, with that decline largely driven by decreases in account servicing fees and transaction fees.”41 This reduction in household bank fees consists mostly of a reduction in so-called ‘exception fees’, for example penalties relating to insufficient funds, over-limit or late-payments (see figure below). We would also observe that this reduction followed the launch of a joint ‘Fair Fees’ campaign from the Consumer Action Law Centre and CHOICE from June 2007. As the campaign gained momentum, the RBA published bank exception fee data for the first time, in its May 2009 bulletin.42 In July 2009, NAB announced it would scrap penalty fees on transaction accounts,43 with other banks announcing reductions in August.44 In May 2010, Maurice Blackburn announced class actions targeting a series of bank exception fees. 45 Given this context, it is difficult to see how this reduction in penalty fees, driven most likely by perceived legal risk and reputational concerns, and largely offset by increases in business fee income over the same period, could be interpreted as an indicator of effective competition. 41 FSI, Interim Report, 2-7 RBA, May 2009, Reserve Bank Bulletin: Banking Fees in Australia: http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2009/may/2.html#f2 43Renouf, Gordon, 30 July 2009, “Bank drops penalty fees. Nice start, long way to go” Crikey: http://www.crikey.com.au/2009/07/30/penalty-fees-just-one-sign-of-a-lack-of-bank-competition/ 44CHOICE, 3 August 2009, Big banks’ fee reduction could be better: http://www.choice.com.au/media-andnews/consumer-news/news/big%20banks%20fee%20reduction%20could%20be%20better.aspx 45 Maurice Blackburn, 12 May 2010, Maurice Blackburn announces legal action against 12 banks: http://www.mauriceblackburn.com.au/about/media-centre/media-statements/2010/maurice-blackburn-announceslegal-action-against-12-banks/ 42 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 20 Australian household bank fee income 1998-2013 ($ million) 6000 Launch of ‘Fair Go on Fees’ campaign RBA first publishes bank exception fee data Launch of first bank fee class actions 5000 4000 Household bank fees ($ million) 3000 Exception fees ($ million) 2000 1000 2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 0 Source: RBA data 3.2. Payment systems Recommendations: A regulator is given explicit legal power to enforce the RBA ruling that limits surcharges to the reasonable cost of acceptance. The RBA regularly assesses and defines a reasonable surcharge rate for different card types based on business size and releases this assessment alongside of average merchant service fee data. That large businesses be required to report to the RBA on the total amount collected annually through surcharges to increase transparency. Interchange fees: CHOICE is wary of any proposal to remove interchange fee caps given the potential for this change to increase costs to both consumers and merchants. Any recommendation on interchange fees needs to take into account consumer outcomes.46 The Inquiry should consider how any change would create products that meet the needs of consumers and assist consumers in making informed decisions to stimulate effective competition. Surcharging: Consumers continue to pay surcharges significantly higher than what it costs merchants to accept payments. Some of Australia’s largest businesses who are best able to negotiate low merchant service fees are charging some of the highest card payment surcharges. There is a tendency for high surcharges to be charged across whole industries, notably the airline, taxi, hotel and ticketing industries.47 For example, the latest analysis from CHOICE, 46 FSI, Interim Report, 3-50. For airline surcharge mark ups see CHOICE, Janurary 2014, Excessive Credit Card Surcharge Update: http://www.choice.com.au/media-and-news/consumer-news/news/credit-card-surcharging-update.aspx 47 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 21 conducted in January 2014, reveals that four of Australia’s largest airlines continue to charge exceptionally high surcharges compared to average merchant service fees. 48 CHOICE supports the Inquiry’s preference to address excessive surcharging rather than to ban surcharging. Returning to a ‘no surcharge’ regime would shift the costs from consumers who choose a specific payment type to all consumers as costs are absorbed into the overall price of goods and services. Such a change would disadvantage consumers using lower cost payment methods like eftpos or cash while subsidising users of high-end credit cards. The most effective solution is to appoint a government agency or regulator to enforce the RBA ruling on limiting card surcharges to the reasonable cost of acceptance.49 This should be done alongside of measures to increase transparency around the amount collected in surcharges compared to the average merchant fee and with the RBA clearly defining appropriate surcharge levels. Individual merchant service fees are confidential although the RBA regularly publishes the average fee retailers pay their bank to accept card payments. Having unique insight into the range of merchant service fees across the economy, the RBA should be responsible for defining the specific appropriate surcharge rate. This could be done with consideration of different business types and sizes, with possible categories of surcharge levels acknowledging that larger businesses are able to negotiate lower merchant service fees. Public companies (over a certain size to exclude small business) should also be required to report annually on the total amount collected in credit card surcharges. This will allow a more transparent evaluation of the gap between average merchant fees and total surcharges. This measure will assist any regulator responsible for assessing the reasonableness of surcharges and provide consumers with transparency about surcharge collection. Merchant routing choice: CHOICE opposes the proposal to allow merchants to choose which scheme to route transactions through once customers have selected credit or debit. CHOICE’s understanding of this proposal, as described by the Australian Retailers Association, is that it would remove consumer choice.50 It is increasingly common for consumers to have a card linked to multiple accounts and offering multiple methods of payment. Should the merchant routing choice recommendation be implemented a consumer would lose the ability to choose either their preferred account or method of payment. For example, if a consumer with a MasterCard or Visa debit card chose to pay through the credit function currently the payment will be routed through the MasterCard or Visa system rather than eftpos. Should this proposal be implemented, a consumer may choose the credit function only to have the payment routed through the debit, or eftpos, function. There are practical differences in these payment systems for consumers including different surcharges at the point of sale, different security guarantees in cases of fraud and the ability to use additional features such as getting cash out at a checkout (currently only available when using eftpos). The most effective way of addressing the issue of different costs a merchant incurs to accept different payment types is to continue the current system which allows a 48 Based on the December 2013 average merchant service fee for MasterCard and Visa: 0.81%., RBA, Payments Data, Credit and Charge Card Statistics http://www.rba.gov.au/payments-system/resources/statistics/index.html 49 RBA, March 2013, Reforms to Payment Card Surcharging http://www.rba.gov.au/paymentssystem/surcharging/index.html 50 Australian Retailers Association, March 2014, Submission to the FSI, p 7. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 22 merchant to send price signals through surcharging to consumers based on the reasonable costs of accepting a payment. 3.3. Post-GFC regulatory response The Interim Report asks for further information on whether it is “possible to reduce the perceptions of an implicit guarantee for systemic financial institutions by imposing losses on particular classes of creditors during a crisis, without causing greater systemic disruption.”51 This follows from the observation that “significant government actions” during the GFC reinforced perceptions that certain institutions are ‘too big to fail’. 52 We note the inquiry’s approach to this issue is very much concerned with ‘perceptions’ of moral hazard and what can be done to credibly reduce them. An alternative view might be that certain institutions are so systemically important to the Australian economy and in fact to the community that no government would ever allow them to fail. In this view, the ‘perception’ of too-big-to-fail reflects the underlying reality. It cannot be credibly reduced - or at least not without exposing consumers of essential banking products and services to unacceptable levels of risk - and efforts would be better directed to addressing competitive distortions resulting from the privileged position of such institutions. As CHOICE observed in our submission on the Financial Claims Scheme (FCS) in 2011, 53 perceptions of institutional safety and stability matter to consumers. For example, the competition impact of a flight to safety of depositors from smaller to larger ADIs would cause consumer detriment, given smaller institutions rely to a greater degree on deposits to compete on key product lines such as home loans: CHOICE believes that these competition concerns are more important to consumers than any other perceived benefits of the FCS. The scheme is designed as a last resort and it is extremely unlikely that the scheme will ever have to act. There are substantial prudential protections in place for Australian financial institutions. These have worked well even in times of extreme crisis. There are also numerous other options that can be pursued to rescue a financial institution before the FCS would need to be triggered. In fact, maintaining the FCS cap at the current level has no obvious downside – it has no on-going costs, any exposure is a very remote possibility, and it maintains a status quo that is working well and has a proven track record of ensuring confidence in all institutions during a period of great stress.54 In response to the Interim Report’s overarching question, we suggest it would be useful to reassess whether the concept of ‘orderly failure’ of a large Australian financial institution is realistic in particular, whether the consumer detriment that would flow from such an event, even with losses imposed on particular classes of creditors, would demand government intervention, irrespective of whether ‘perceptions’ had been reduced. 51 FSI, Interim Report, 3-12. FSI, Interim Report, 3-9. 53 CHOICE, June 2011, Submission to The Financial Claims Scheme Consultation Paper: http://archive.treasury.gov.au/documents/2084/PDF/CHOICE.pdf 54 Ibid, p 4. 52 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 23 3.4. Macro prudential tool kits CHOICE has noted a recent increase in risky home loans. CHOICE has raised specific concerns with no deposit, low deposit, family guarantee and 40-year loan products growing in popularity.55 CHOICE welcomes further consideration of alternative macro prudential arrangements, particularly the arrangements mirroring the move in New Zealand to limit the amount of total lending for loans with a high LVR. However, it is CHOICE’s view that the current regulatory arrangements should be sufficient to manage such developments on both a prudential and consumer protection level, but that adequate resourcing of regulators is necessary to see this role fulfilled. 3.5. Compensation arrangements Recommendation: That a statutory compensation scheme modelled on the Financial Services Compensation Scheme in the United Kingdom is established to address unpaid determinations. CHOICE echoes the Financial Ombudsman Service’s concerns about unpaid determinations and uncompensated loss. While of course it is preferable to prevent misconduct and loss in the first place, there is a clear need for a last-resort compensation scheme. Given the limitations of professional indemnity insurance, CHOICE would like to see the establishment of a statutory compensation scheme modelled on the UK Financial Services Compensation Scheme. However, should this not be established, CHOICE would support a “minimalist” scheme as proposed by the Superannuation Consumers Centre or for ASIC approved complaints schemes to amend their terms of reference so that they can compensate consumers with unpaid determinations. 3.6. Insurance Recommendations: The Government initiates a review of consumer outcomes and competition in insurance, particularly in the context of climate risk. CHOICE endorses the work of the Financial Rights Legal Centre and their recommendations on insurance. CHOICE would add to this that Australians have experienced significant premium increases across a range of insurance products in recent years. The availability and affordability of various insurance products suggests further examination of this sector is warranted. As noted in the Interim Report, the top two insurers have approximately 60 per cent market share in general insurance. We see this as a sign of inadequate competition and there is evidence that this results in poor consumer outcomes. In comparable countries such as the United Kingdom insurance premiums have sharply decreased and investment returns have declined. In comparison, in the Australian insurance sector premiums have grown dramatically. 55 CHOICE, 6 May 2014, Banks offer risky home loans: http://www.choice.com.au/reviews-andtests/money/borrowing/your-mortgage/risky-home-loans.aspx CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 24 While investment returns have declined from a high in 2008, they remain the highest amongst comparable nations.56 These problems have been aggregated by increased climate risk. CHOICE directs the Inquiry to the report Buyer-Beware: Home Insurance, Extreme Weather and Climate Change.57 The report found that due to underinsurance, homeowners can receive insurance pay-outs equating to less than half that is required to replace their home and that in some high-risk locations premiums cost ten times more than typical policies for low-risk locations. CHOICE supports the report’s conclusion that more needs to be done to disclose risk to homeowners and buyers. Currently it is a “buyer beware” market, with consumers left to navigate the complex risks with little support. Many buyers are unaware that they may be buying a home in a high-risk area. Consumers must be provided with more information about risk assessments in their local area to assist with initial purchasing decisions as well as to justify any insurance premium rises linked to hazards such as floods.58 This will require coordination between local, state and federal governments as well as insurers. We believe that the problems of complexity, inadequate competition and complexity for consumers justify a much deeper analysis of problems in the insurance market than that presented in the Interim Report, which is why we encourage the Inquiry to recommend a discrete review of insurance as a high priority. 3.7. Regulatory Architecture CHOICE sees a continued need for financial services specific regulation and agrees with the observation that Australia has strong, well-regarded regulators but that more could be done to increase independence and accountability.59 CHOICE supports the move to provide ASIC and APRA with a more autonomous budget and funding process. CHOICE also supports an increase to the civil and administrative penalties available to ASIC. Current penalties are not proportionate to the harm that can be caused through corporate wrongdoing. Penalties are also less likely to act as commercially significant sanctions at their current levels. Self-regulation: CHOICE supports self-regulation where appropriate. CHOICE agrees with the Superannuation Consumers Centre that there are three drivers of successful self-regulatory initiatives, being: - shared governance arrangements with equal numbers of consumer and industry representatives with an independent chair; - periodic external review of arrangements; and, 56 Bank of International Settlements, June 2014, The financial system at a crossroads, figure 5: http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2014e6.htm 57 Climage Risk Proprietary Ltd, 2014, Buyer-Beware: Home Insurance, Extreme Weather and Climate Change: A report to the Climate Institute of Australia in partnership with CHOICE. 58 See CHOICE, 31 January 2013, Home and contents premium hikes: http://www.choice.com.au/reviews-andtests/money/insurance/house-and-car/home-and-contents-premium-hikes.aspx and CHOICE, 5 June 2014, Home insurance and climate change: http://www.choice.com.au/media-and-news/consumer-news/news/home-insuranceand-climate-change-050614.aspx 59 FSI, Interim Report, 3-108. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 25 - approval of arrangements by ASIC against agreed standards specified in RG 139 and RG 183. Self-regulatory arrangements can be successful because they involve industry members working together to evolve practices. CHOICE maintains that the involvement of consumer representatives in development and administration of arrangements is crucial to any initiative’s success. In addition, all financial services industry codes should be required to be registered and approved by ASIC. 3.8. Emerging Trends: Open Data Recommendations: Government should work with industry, consumer groups and privacy and security experts to develop an open data scheme. As a secondary goal this group should consider opportunities for releasing de-identified data for public use. Navigating the banking and finance sector is a difficult experience for consumers, with many telling CHOICE that they feel powerless when dealing with financial institutions. Financial products are the most complicated products on the market; the CHOICE June 2014 National Pulse Check reveals that large numbers of consumers feel that super funds (47 per cent), mortgages (44 per cent), home and contents insurance (39 per cent) and car insurance (35 per cent) are complicated to choose. It is often impossible for an individual consumer to understand the terms and conditions of the increasingly complex products on offer. Additionally, many consumers do not trust in the information and advice that they can access. Consequently, most consumers on their own are unable to make fully informed choices as to what are the most appropriate products for their needs. Significant savings could be achieved if product complexity and opacity was reduced, and if tools facilitating consumers’ searches for better products were provided. For instance, a recent study found that 93 per cent of consumers in the US were under the impression that they were paying less in retirement fund fees than was the case. The study further notes that if just ten per cent of the consumers in the highest fee plans were to make a switch to a fund charging the average fee, savings of up to $10 billion per year could be realised.60 Lack of knowledge regarding products and fee structures is also an issue for Australian consumers, with 48 per cent of CHOICE survey respondents in 2013 unsure of the interest rate that applied to their credit purchases.61 Similarly significant numbers noted that the inability to find better products was their key reason for not switching (26 per cent for savings accounts, 19 per cent for transaction accounts and 18 per cent for credit cards).62 Providing consumers with relevant, accessible information about the products they consume and the way in which they do so could improve both the individual consumer experience and the overall competitiveness of the marketplace. Coupling the release of this information with the 60 Manyika J et. al. October 2013, Open Data: Unlocking innovation and performance with liquid information,, McKinsey Global Institute, http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/business_technology/open_data_unlocking_innovation_and_performance_with_li quid_information 61 CHOICE, 2013, Credit card interest survey, http://www.choice.com.au/media-and-news/consumernews/news/credit-card-interest-survey.aspx 62 CHOICE, March 2014, Submission to the Financial System Inquiry.. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 26 development of user-friendly comparator tools could address the issue outlined above, reducing consumer confusion and simplifying the ways in which individuals engage with the market. One option for achieving these goals would be to implement an “open data” policy similar to that in operation in the UK. The UK experience: Midata The UK’s Midata programme was launched in 2011. A voluntary scheme, it is based on the key principle that consumers’ data should be released back to them in a uniform, secure, machine-readable format. The scheme intends to help consumers make meaningful comparisons about the different products on offer in four key markets: energy, bank accounts, credit cards and mobile phone plans. The value of consumer data in these sectors is substantial, as consumers often enter into lengthy contracts for products that are complex and difficult to compare. Recently, as part of the Midata programme, a number of the UK’s major banks signed an agreement with the government to make their customers’ data available to them in a simple, uniform format. A new account comparison tool will be developed by April 2015, enabling customers to input their standardised data and easily assess whether it would be in their interests to switch to a different account. Implementing a scheme in Australia based on Midata could benefit consumers by: a) Empowering individuals, enabling them to make better informed decisions based on their personal preferences, consumption habits and needs; and b) Encouraging innovation, competition and the development of a broader range of more useful products for consumers, as third parties analyse available open data and identify possibilities for new products and services. One of the key reasons for pursuing open data policies is to empower consumers by providing them with access to their own data, consequently reducing information asymmetries in complex markets. CHOICE research has found that the market for credit cards is excessively complex, and that consumers would benefit from tools that enable them to more effectively and efficiently match product options to their individual circumstances. CHOICE research in 2010 found that comparing credit card offerings on a like-for-like basis was virtually impossible for consumers, with at least 10 different interest billing methods being used by companies. These different billing methods can dramatically vary the end cost to a consumer. In addition to fees, credit card rewards can also vary depending on the consumer habits. A card that appears to have a strong travel reward system might in fact cost a consumer more in annual fees than it generates in benefits, if that consumer is a low monthly spender ($1000 or less).63 A trusted third party would need access to the data that demonstrates how a consumer spends 63 CHOICE, 6 October 2010, Travel rewards credit cards, http://www.choice.com.au/reviews-andtests/money/borrowing/credit-cards/travel-rewards-credit-cards.aspx CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 27 money, how much they are spending, and the time periods in which they repay debts in order to provide more meaningful comparisons about the range of products on offer that would best suit the individual. The two images below outline the data flows occurring today and data flows under a possible midata system. Simply making data available will not result in better informed consumers and more competitive markets – it is necessary that the data also be accessible and useable. The United States’ “smart disclosure” policy memorandum provides some guidelines to ensure that data is not merely released, but is provided to consumers in a format that will aid their ability to make informed decisions. CHOICE agrees that the characteristics of smart disclosure include accessibility, machine readability, standardisation, timeliness, interoperability and privacy protection.64 Providing consumers with access to their own data in a convenient format could improve their ability to drive competition on the demand side, by rewarding those businesses that best meet their needs or preferences, and consequently encouraging the development of new products and services. 64 US Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, 8 September 2011, Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies, Informing Consumers Through Smart Disclosure, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/inforeg/for-agencies/informing-consumers-through-smartdisclosure.pdf CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 28 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 29 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 30 Releasing and sharing data Releasing and sharing data in a de-identified, secure format can also promote third party innovation and encourage price-based competition. Products and services that meet consumers’ needs more efficiently than current offerings can be identified and developed when transaction and consumption data is made available. Benefit: Informed Consumers Providing consumers with access to their own data in a useful format can lead to more engagement, empowerment and better informed decision-making. For example, uBank has a significant amount of consumer data available to it, in the form of transaction records. This data has been de-identified and presented on the website ‘PeopleLikeU’ with the aim of providing consumers with an easy-to-use tool for comparing their own habits with those of the broader population. An individual might use the website to check what the average energy bill is in their neighbourhood. This information can then be used to make a decision to seek out a better deal. If a consumer had access to personal data on their own spending habits (when coupled with an appropriate comparator tool), they could use this information to decide whether a credit card with a different fee structure would better meet their individual needs, or if a specific loyalty program might match their shopping habits. However, when making data available to third parties the gains for consumers must be balanced against the risk of privacy breaches. If privacy concerns are not addressed, this may lower consumer confidence in the market and cause overall consumer detriment. Robust privacy safeguards are a necessary precondition for expanding any open data policies in Australia to encompass third party access. Benefit: Third Party Innovation BillGuard is one example of a useful consumer product that developed after a third party was given access to previously inaccessible data. BillGuard does two key things: it maintains an up-to-date list of merchants who have been affected by data breaches, and it tracks BillGuard users’ spending on a store-tostore basis. Using these two data sets, BillGuard sends users an alert if a store they have shopped at recently has experienced a data breach. The app also provides advice to affected users, and closely monitors their accounts in the days following a breach for suspicious transactions. BillGuard has received praise for responding to instances of data breaches more rapidly and with more relevant information than consumers’ banks and credit card providers. The app has been available for customers of some Australian banks to use since January 2014. CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 31 As another first round submission noted65, ‘big data’ is providing significant value to businesses seeking to refine and market their products more effectively. On a global scale, governments are seeking to ensure that consumers also benefit from this trend. Nations including the UK, the US, Canada and Japan have made a public statement that “open data are an untapped resource with huge potential” and can enable people to “make better informed choices about the services they receive and the standards they should expect”.66 The Australian Government should not fall behind its international counterparts, but should equally consider opportunities for utilising data to empower consumers and promote competition and innovation. 65 ASIC, April 2014, Financial System Inquiry: Submission by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. Cabinet Office United Kinkdom, 18 June 2013, G8 Open Data Charter and Technical Annex: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/open-data-charter/g8-open-data-charter-and-technical-annex 66 CHOICE Submission: FSI Interim Report (August, 2014) Page | 32