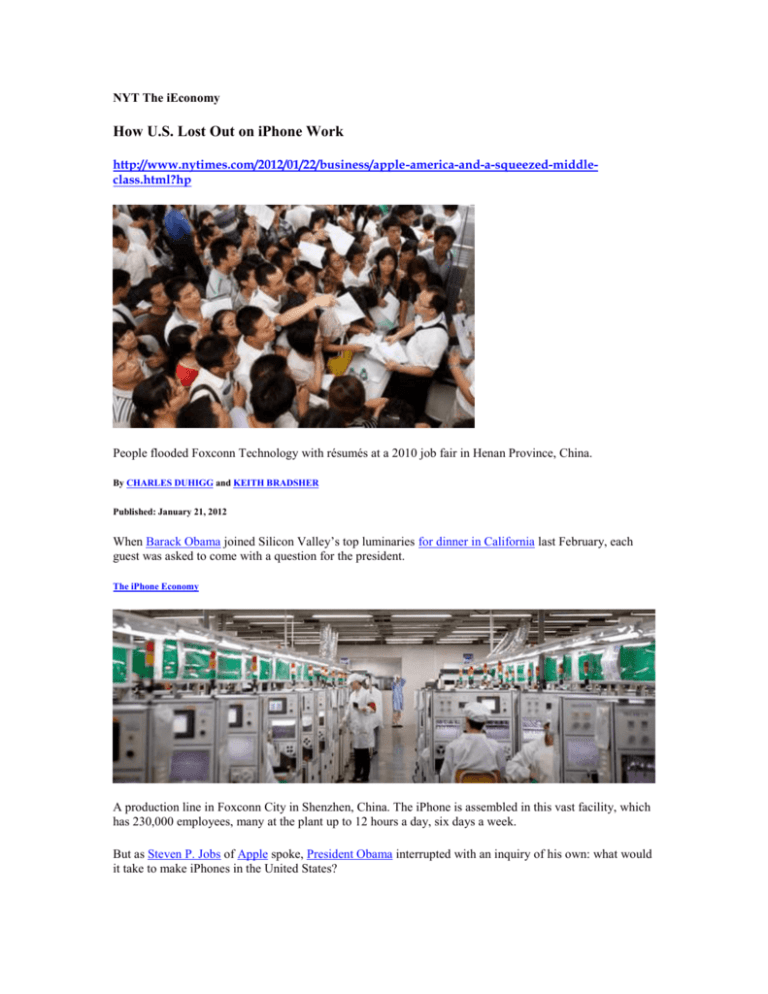

The iEconomy

advertisement