Modern Latin American History - The University of Texas at Tyler

advertisement

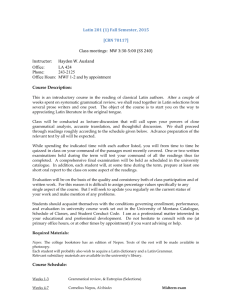

Modern Latin American History HIST 4392-001 Dr. Colin Snider – Department of History BUS 267 csnider@uttyler.edu 903-565-5758 Office Hours: Mondays, 3:30-5:00 PM Wednesdays, 8:30-10:00 AM Or by Appointment Course Description This course looks at the peoples, cultures, and events of Latin America from 1810 to the present. From the beginning of independence movements to the rise of the “New Left” in the 21st century, from the abolition of slavery to indigenous rights struggles in the twentieth century, from the age of caudillos to the rise of military regimes, from women’s struggles to the region’s relations with the US, from tango and samba to salsa and reggaeton, this course will allow students to understand the cultural, social, economic, and political complexities of societies and cultures in post-independence Latin America while providing points of comparison and contrast between Spanish and Portuguese America. Through the use of primary documents, secondary readings, film, music, and other materials, we will look at the ways societies, cultures, politics, and economies from Mexico to the Tierra del Fuego operated and changed over time. Texts and Readings This course relies on a mixture of secondary and primary sources in order to get students to understand early American history as the people lived it. These sources also allow students to consider how history is produced, who produces it, and how it is used and interpreted. Students will read an average of 100-175 pages a week (though some weeks may be over 175 pages, and others may be under 100 pages). In addition to the books listed below, there will also be primary source readings throughout the semester that will be made available on Blackboard. Readings are due on the date they are listed on the syllabus. Textbooks will be available in the bookstore. Unless otherwise noted, all the books below are required reading. Books marked with an asterisk are also available on Kindle. The books for this class are: *Dawson, Alexander. Latin America since Independence: A History with Primary Sources. New York: Routledge, 2010. [Recommended] (ISBN: 978-0415991964) *O’Connor, Erin. Mothers Making Latin America: Gender, Households, and Politics Since 1825. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2014. (ISBN: 978-1118271445) Sanders, James E. The Vanguard of the Atlantic World: Creating Modernity, Nation, and Democracy in Nineteenth-Century Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014. (ISBN: 978-0822357803) Wasserman, Mark. The Mexican Revolution: A Brief History with Documents. New York: Bedford/St. Martins, 2012. (ISBN: 978-0312535049) Levine, Robert M. The Life and Death of Carolina Maria de Jesus. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995. (ISBN: 978-0826316486) *Tinsman, Heidi. Buying Into the Regime: Grapes and Consumption in Cold War Chile and the United States. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014. (ISBN: 978-0822355359) *Menchú, Rigoberta. I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala. New York: Verso Books, 2010. (ISBN: 978-1844674183) Course Requirements Students are required to attend lectures and participate in discussions. A full 10% (one letter grade) of the student’s grade will be based on attendance and participation in the classroom. There will be many times where we discuss the readings, as well as films we will be watching throughout the semester, and students are fully expected to complete the readings on time and to engage in discussion with one another and with the professor in the classroom. In the event that it becomes clear that students are not doing the assigned readings on time, pop quizzes may become a regular feature of the course. Writing is an essential party of historical study and analysis, and of the liberal arts tradition of education more generally; as a result, students will be given a number of writing assignments. The first of these are a series of five (5) short primary source analyses based upon the primary documents in O’Connor’s Mothers Making Latin America. These are relatively short assignments, in which students are to consider a document from a week’s reading and to provide a brief analysis of a primary source assigned for that week. The form for these short analyses is available on blackboard. You will have nine opportunities to complete the five analyses, meaning students are welcome to pick which sources they analyze from a chapter in the week they turn in the analyses. Collectively, these primary source analyses are worth 15% of the student’s final grade (3% per analysis). In addition to these short analyses, students will also write analytical papers that ask them to consider the readings from the class from a variety of conceptual and 2 thematic angles. There will be five paper assignments, and students are expected to write three of the four papers. These papers will focus on the book-length readings from the class reading list; outside research will not be necessary. Each paper should be 4-5 pages in length, and each paper will make up 15% of the student’s grade, for a total of 45% of the student’s final grade. If students would like, they may write a fourth paper for extra credit; the grade on the fourth paper will replace the lowest grade from the first three papers. All papers will be submitted electronically through Blackboard, with the professor providing specific instructions as the due date approaches. Students are welcome to bring by drafts of their papers at any time before the due date as well, and they are also encouraged to use the Writing Center (located in BUS 202; phone – 903-565-5995). Finally, in order for students to demonstrate the broader materials students have learned, there will also be a midterm exam and a final exam, each worth 15% of the student’s final grade. These exams will be in class exams and will focus on important terms/ideas and themes from the lecture materials. Test materials will come from class lecture notes and readings, which is another reason why attendance and participation are so important. Grades As outlined above, the grades will be determined in the following manner: Primary Source Analyses (five at 3% each): Paper 1: Paper 2: Paper 3: Mid-Term Exam: Final Exam: Attendance & Participation: TOTAL: 15% 15% 15% 15% 15% 15% 10% 100% Classroom Etiquette While college can be a fun environment, it is also a learning environment, and a place where certain precepts of etiquette should be followed out of respect for your peers. In general, if you are in class, you are here to learn, not to focus on other matters; if you don’t want to be there, then you should reconsider whether or not you should be enrolled in school. With that in mind, please: Be on time: Sometimes something happens that delays your arrival to class (scheduling, distance between buildings, etc.), but in general, habitual lateness is distracting to your colleagues. Do not leave early: Once you are in the classroom, you should plan on 3 staying through the class – departing because you feel like it is both disrespectful and distracting to your colleagues. If you think you may have to leave early, please sit near the door and leave in a quiet fashion. Put away your cell phones: Yes, in this time, it is very easy to become compulsive about checking phones. However, you are here to learn; excepting in the case of an emergency, please do not take out your phones, answer your phones, send text messages in class, play games on your phone, or otherwise use your phone as a distraction, as it is both distracting and disrespectful. If you are expecting a really important call (i.e., a sick family member, etc.), please alert the professor before class. Computer use: Some students have become accustomed to using computers in the class. However, they are also an easy distraction for those in the classroom. This has included using social media, playing video games, and even watching movies in class. Unfortunately, as a result, based on the past experiences and actions of students in class, the use of laptops, tablets, and other devices is COMPLETELY PROHIBITED without prior consultation with the professor. Academic Integrity The faculty expects from its students a high level of responsibility and academic honesty. Because the value of an academic degree depends upon the absolute integrity of the work done by the student for that degree, it is imperative that a student demonstrates a high standard of individual honor in his or her scholastic work. Definition of Academic Dishonesty Scholastic dishonesty includes, but is not limited to, submitting work that is not one’s own. In the classroom, this generally takes one of two forms: plagiarism or cheating. Cheating can include (but is not limited to) using unauthorized materials to aid in achieving a better grade, inventing information, including citations, on an assignment, and copying answers from a colleague or other source. Plagiarism is presenting the words or ideas of another person as if they were your own. Plagiarism can include, but is not limited to, submitting work as if it is your own when it is at least partly the work of others, submitting work that has been purchased or obtained from the internet or another source without authorization, and incorporating the words and ideas of another writer or scholar without providing due credit to the original author. Any and all cases of plagiarism or cheating will result in an automatic zero for the 4 assignment. The professor also reserves the right to assign the students a zero for the semester, and to refer cases of plagiarism to the student’s respective dean. Please read the complete policy at http://www.uttyler.edu/judicialaffairs/scholasticdishonesty.php Incomplete Policy In accordance with UT-Tyler policy, “Should the student fail to complete all of the work for the course within the time limit, then the instructor may assign zeroes to the unfinished work, compute the course average for the student, and assign the appropriate grade.” Therefore, it is incumbent upon the student to do the work during the semester, as the professor is not required to give an incomplete for unfinished assignments without thoroughly documented evidence of extenuating circumstances. It is the professor’s prerogative to determine whether or not a student’s individual circumstances merit an incomplete, and in the rare instances when such circumstances arise, students must meet with the professor as soon as they occur. For more information, see the UT-Tyler policy at http://www.uttyler.edu/registrar/policies/incompletes.php Student Rights and Responsibilities To know and understand the policies that affect your rights and responsibilities as a student at UT Tyler, please follow this link: https://www.uttyler.edu/wellness/rightsresponsibilities.php Grade Replacement/Forgiveness and Census Date Policies Students repeating a course for grade forgiveness (grade replacement) must file a Grade Replacement Contract with the Enrollment Services Center (ADM 230) on or before the Census Date of the semester in which the course will be repeated. Grade Replacement Contracts are available in the Enrollment Services Center or at http://www.uttyler.edu/registrar. Each semester’s Census Date can be found on the Contract itself, on the Academic Calendar, or in the information pamphlets published each semester by the Office of the Registrar. Failure to file a Grade Replacement Contract will result in both the original and repeated grade being used to calculate your overall grade point average. Undergraduates are eligible to exercise grade replacement for only three course repeats during their career at UT Tyler; graduates are eligible for two grade replacements. Full policy details are printed on each Grade Replacement Contract. The Census Date is the deadline for many forms and enrollment actions that students need to be aware of. These include: 5 Submitting Grade Replacement Contracts, Transient Forms, requests to withhold directory information, approvals for taking courses as Audit, Pass/Fail or Credit/No Credit; Receiving 100% refunds for partial withdrawals. (There is no refund for these after the Census Date); Schedule adjustments (section changes, adding a new class, dropping without a “W” grade); Being reinstated or re-enrolled in classes after being dropped for nonpayment; Completing the process for tuition exemptions or waivers through Financial Aid. State-Mandated Course Drop Policy Texas law prohibits a student who began college for the first time in Fall 2007 or thereafter from dropping more than six courses during their entire undergraduate career. This includes courses dropped at another 2-year or 4-year Texas public college or university. For purposes of this rule, a dropped course is any course that is dropped after the census date (See Academic Calendar for the specific date). Exceptions to the 6-drop rule may be found in the catalog. Petitions for exemptions must be submitted to the Enrollment Services Center and must be accompanied by documentation of the extenuating circumstance. Please contact the Enrollment Services Center if you have any questions. Students with Disabilities To obtain disability related accommodations, alternate formats and/or auxiliary aids, students with disabilities must contact the Office of Disability Services (ODS), Human Services Building, and Room 325, 468-3004 / 468-1004 (TDD) as early as possible in the semester. Once verified, ODS will notify the course instructor and outline the accommodation and/or auxiliary aids to be provided. Failure to request services in a timely manner may delay your accommodations. For additional information, see http://www2.uttyler.edu/disabilityservices/. Student Absence due to Religious Observance Students who anticipate being absent from class due to a religious observance are requested to inform the instructor of such absences by the second class meeting of the semester. Student Absence for University-Sponsored Events and Activities If you intend to be absent for a university-sponsored event or activity, you (or the event sponsor) must notify the instructor at least two weeks prior to the date of the 6 planned absence. At that time the instructor will set a date and time when make-up assignments will be completed. Social Security and FERPA Statement: It is the policy of The University of Texas at Tyler to protect the confidential nature of social security numbers. The University has changed its computer programming so that all students have an identification number. The electronic transmission of grades (e.g., via e-mail) risks violation of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act; grades will not be transmitted electronically. Emergency Exits and Evacuation: Everyone is required to exit the building when a fire alarm goes off. Follow your instructor’s directions regarding the appropriate exit. If you require assistance during an evacuation, inform your instructor in the first week of class. Do not re-enter the building unless given permission by University Police, Fire department, or Fire Prevention Services. 7 Course Schedule Week 1 – Intro Readings: O’Connor, Chapters 1 and 2 Monday, January 12: Introduction Wednesday, January 14: The Americas on the Eve of Independence Friday, January 16: Varying Paths to Independence, 1810-1824 Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #1 Week 2 – The Challenge of State Formation in 19th Century Latin America Readings: O’Connor, Chapter 3 Monday, January 19: Martin Luther King, Jr. Day – No Class Wednesday, January 21: A Nation for Whom? Nation-State Building in Latin America, 1820s-1830s Friday, January 23: The Age of Caudillismo in Latin America Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #2 Week 3 Readings: Sanders, The Vanguard of the Atlantic World Monday, January 26: An Empire Amidst Republics: The Brazilian Empire, 1821-1889 Wednesday, January 28: Wars Civil and Foreign: Commodities and Competition in Spanish America Friday, January 30: Nations for Whom? Nineteenth-Century Latin American Society & Democracy In-Class Discussion of Sanders, The Vanguard of the Atlantic World Week 4 – Latin America’s Fin de Siècle Readings: O’Connor, Chapter 4 Monday, February 2: Race, Nation, Citizenship, and Identity in Late Nineteenth Century Latin America Paper 1 Due by 10:00 AM Wednesday, February 4: Liberalism’s Ascent in Late Nineteenth Century Latin America Friday, February 6: A Turbulent Turn of the Century Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #3 Week 5 – The Mexican Revolution Readings: Wasserman, The Mexican Revolution Monday, February 9: ¡Revolución!, 1910-1920 Wednesday, February 11: Culture and Society during ¡Revolución! 8 Friday, February 13: The Costs of Revolution in Mexico In-Class Discussion of Wasserman, The Mexican Revolution Week 6 – The End of Latin America’s “Long Nineteenth Century”: 1900-1929 Readings: O’Connor, Ch. 5 Monday, February 16: Social Mobilization and Politics in Latin America Paper 2 Due by 10:00 AM Wednesday, February 18: The End of an Empire: Brazil’s First Republic, 1889-1930 Friday, February 20: The Great Depression and Latin America Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #4 Week 7 – Populism and Nationalism in Latin America, 1920s-1940s Readings: O’Connor, Ch. 6, and primary sources on Populism, available on Blackboard Monday, February 23: The Rise of Populism – The 1920s and 1930s Wednesday, February 25: Populism and the People(?) – 1930s-1940s Friday, February 27: Latin America and World War II Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #5 Week 8 – Shifting Politics in the Postwar Era Readings: Levine, Life and Death of Carolina Maria de Jesus Monday, March 2: What Kind of Neighbor? US-Latin American Relations, 1945-1954 Wednesday, March 4: Of Democracy and “Development” in Postwar Latin America Friday, March 6: The Face of “Modernity”? Life in the 1950s In-Class Discussion of Levine, Life and Death of Carolina Maria de Jesus Week 9 – SPRING BREAK Week 10 – Polarization, Politics, and Society in Latin America, 1950s-1960s Readings: O’Connor, Ch. 7 Monday, March 16: The Cuban Revolution Wednesday, March 18: Latin American Radicalization… Friday, March 20: …and Conservative Reaction in Latin America Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #6 Week 11 – The Rise of Bureaucratic Authoritarianism Readings: O’Connor, Ch. 8 Monday, March 23: Dictatorship and “Democracy” In South America Wednesday, March 25: In-Class Film: Machuca Friday, March 27: In-Class Film: Machuca Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #7 9 Week 12 – Life Under Dictatorship Readings: Tinsman, Buying Into the Regime Monday, March 30: Finish Machuca and discuss in class Wednesday, April 1: Resistance and Survival in Authoritarian Regimes Friday, April 3: Authoritarian Regimes in the International Setting In-Class Discussion of Tinsman, Buying Into the Regime Week 13 – The Uneven 80s: Civil War and Democratization in Latin America Readings: Menchú, I, Rigoberta Menchú Monday, April 6: A Return to Democracy in South America, 1983-1990 Paper3 Due by 10:00 AM Wednesday, April 8: The (Counter)-Revolution Moves North: Civil Wars in Central America, 1979-1996 Friday, April 10: Ethnicity and Struggle in the Face of Genocide In-Class Discussion of Menchú Week 14 – Life amidst Democratization and Destabilization Readings: O’Connor, Ch. 9 Monday, April 13: Latin America and the World in the 1980s Wednesday, April 15: The Neoliberal Nineties Paper 4 Due by 10:00 AM Friday, April 17: Latin American Culture & Society on the Eve of a New Millennium Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #8 Week 15 – A Promising Future? Latin America in the 21st Century Readings: O’Connor, Ch. 10 Monday, April 20: Political Unrest, Political Transformation in the 21st Century Wednesday, April 22: Regional Issues, Social Movements and Transnational Connections in the 21st Century Friday, April 24: Latin America Today Primary Source Analysis Opportunity #9 10