Link - Filippo Rebessi

advertisement

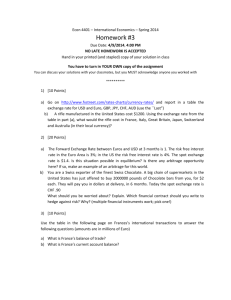

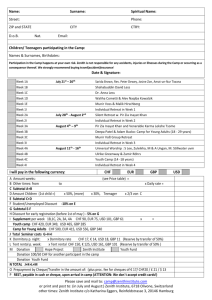

Econ 4401 – International Economics – Spring 2014 Homework #3 Suggested Solution ********** 1) [10 Points] a) Go on http://www.fxstreet.com/rates-charts/currency-rates/ and report in a table the exchange rate for USD and Euro, GBP, JPY, CHF, AUD (use the ``Last”) EUR/USD GBP/USD USD/JPY USD/CHF AUD/USD 1.378 1.675 102.007 .8838 .9369 b) A rifle manufactured in the United States cost $1200. Using the exchange rate from the table in part (a), what would the rifle cost in France, Italy, Great Britain, Japan, Switzerland and Australia (in their local currency)? The only thing we need to be careful about here is to interpret the numbers correctly. For example: EUR/USD=1.378 means that it takes $1.378 to make 1 Euro. Consequently, I can buy the rifle in any country that adopts the Euro for 1200/1.378=Euro 870.82 On the other hand, when the exchange rate is quoted as USD/Other currency=k, we have to interpret it as: “it takes k units of Other currency to make $1”. So, for example, we read USD/JPY=102.007 as: it takes JPY 102.007 to make $1. The cost of the rifle in Japan will be JPY 1200*102.007 France and Italy Great Britain Japan Switzerland Australia EUR/USD =1.378 GBP/USD =1.675 USD/JPY =102.007 USD/CHF=.8838 AUD/USD=.9369 Rifle Cost Eur 1200/1.378=870.82 GBP 1200/1.675=716.41 JPY 1200*102.007=122408.4 CHF 1200*.8838=1060.56 AUD 1200/.9369=1280.81 2) [20 Points] a) The Forward Exchange Rate between Euros and USD at 3 months is 1. The risk free interest rate in the Euro Area is 3%; in the US the risk free interest rate is 4%. The spot exchange rate is $1.4. Is this situation possible in equilibrium? Is there any arbitrage opportunity here? If so, make an example of an arbitrage for this world. We can use the covered interest rate parity, which gives us the formula for the forward exchange rate: i$=ieur+(F-E)/E. If this does not hold with equality, then we can come up with some arbitrage strategy. Plugging in the numbers we obtain: i$=.04 ieur+(F-E)/E=.03 + (1 -1.4)/1.4 = .03 + (-.4)/1.4 = .03 – 0.28 =- 0.2557 Clearly i$>ieur+(F-E)/E ! The forward rate is (way) lower than it should be. This situation won’t last forever! Either the interest rate in Europe will shoot up, or the forward rate will. This is a good moment to borrow in Euro, purchasing the forward rate at 1, and invest in dollars. Each Euro you borrow today would cost you $1.4 if you had to pay back immediately; however, the forward contract allows you to fix a lower rate of conversion in the future, when you will have to pay back the money: $1. In a situation like this (Forward discount), the interest rate in the Euro area should be much higher than the interest rate in the US. However, on the euros you borrow, according to our data, you owe 3%; you can take your loan, convert it today in dollars at the spot rate (each Euro buys you $1.4) and invest at 4%. You are bringing home a positive interest rate differential (4% - 3%) and with the forward contract, you have secured a lower rate of conversion of $ in Euros in the future: this is a (large) free meal (or arbitrage). b) You are a Swiss exporter of the finest Swiss Chocolate. A big chain of supermarkets in the United States has just offered to buy 2000000 pounds of Chocolate bars from you, for $2 each. They will pay you in dollars at delivery, in 6 months. Today the spot exchange rate is CHF .90 What should you be worried about? Explain. Which financial contract should you write to hedge against risk? Why? (multiple financial instruments work; pick one!) As a Swiss exporter, your consumption is priced in Swiss Francs (CHF). However, you are getting paid in $. The exchange rate is the price of $, or, in other words, how many CHF it takes to make one $. If this price goes down (less CHF for 1$), for each $ you get paid, you will obtain less CHF in exchange. This is situation is an appreciation of the Swiss Franc, and this is what should be concerned about. One financial contract that works is a Future: you can fix today the rate of conversion of $ into CHF in 6 months and forget about the risk that the spot exchange rate will fall below the Future. Another instrument that works is a PUT option on CHF/$. This instrument gives you the right to sell $ for CHF at a given “strike price”. If in the future the CHF appreciates above the strike price (i.e. it takes less CHF than the strike to make a $), then you will exercise your put option and sell $ at the established strike price. 3) [10 Points] Use the table in the following page on Frances’s international transactions to answer the following questions (amounts are in millions of Euro) a) What is France’s balance of trade? It’s Merchandise Exports - Merchandise Imports : -1000 b) What is France’s current account balance? It’s (Merchandise Exports – Merchandise Imports) + (Service Exports – Service Imports) + (Inv. Income Receipts – Inv. Income Payments) + Net Unilateral Transfers = ( -1000 ) + (+5000) + (+18000) + (-1000) = 21000 Transaction Merchandise Imports Merchandise Exports Service Imports Service Exports Investment Income Receipts Investment Income Payments Gifts (Net Unilateral Transfers) Amount 93000 92000 15000 20000 43000 25000 -1000 4) [10 Points] This part of the homework requires you to use FRED. http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/categories/32951 a) Create ONE picture with Current Account (Excludes Exceptional Financing) for China, USA and Germany (they have to be all on the same graph). [5 points] (See next page) 600000000000 USA 400000000000 China Germany 200000000000 0 -200000000000 -400000000000 -600000000000 -800000000000 -1000000000000 b) Many economic commentators think that Germany and China should engage in expansionary policies (either through monetary or fiscal policy), to solve the problem of “Global Imbalances” (i.e. the US current account balance being very negative and Germany and China’s C.A.B. being very positive). Looking at the graph you created, do you think that would help? Explain. [5 points] Not necessarily: Germany and China’s current accounts (the overall sum of the past current account balances), according to the graph, have been almost flat from the beginning of the 80s to the beginning of 2000. This means that their CAB was basically 0 during that period of time. Notice how that didn’t stop the US from accumulating big CAB deficits: from 1983 to 1989 and after 1993. The graph doesn’t seem to imply that a CAD surplus in China or Germany implies a CAB deficit in the US and viceversa!