Debt-Equity Choice - Yale School of Management

advertisement

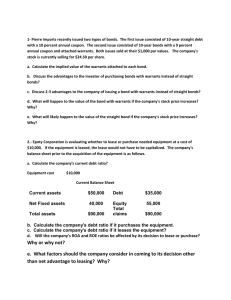

Debt-Equity Choice Playing Games with Taxes and Incentives Types of Debt Financing • • • • 1. Bank loans 2. Leases 3. Commercial Paper 4. Corporate Bonds Bank Loans • Line of credit – An arrangement between a bank and a firm that requires the bank to quote an interest rate, typically for a short-term loan, when the firm requests the loan. The bank authorizes the maximum loan amount when setting up the line of credit. • Loan commitment – An arrangement that requires a bank to lend up to a maximum prespecified loan amount at a prespecified interest rate at the firm’s request as long as the firm meets the requirements established when the commitment was drawn up. There are two types of loan commitments: • Revolver, in which funds flow back and forth between the bank and the firm without any predetermined schedule. Funds are drawn from the revolver whenever the firm wants them, up to the maximum amount specified. They may be subject to an annual cleanup in which the firm must retire all borrowings. • Nonrevolving loan commitment in which the firm may not pay down the loan and then subsequently increase the amount of borrowing. Leases • A debt instrument in which the owner of an asset, the lessor, gives the right to use the asset to another party, the lessee, in return for a set of contractually fixed payments. – Operating lease: An agreement, usually short term, allowing the lessee to retain the right to cancel the lease and return the asset to the lessor. – Financial lease (or capital lease): An agreement that generally extends over the life of the asset and indicates that the lessee cannot return the asset except with substantial penalties. • Leveraged lease (asset purchase financed by a third party), • Direct lease (asset purchase financed by the manufacturer of the asset), and • Sale and leaseback (asset purchased from the lessee by the lessor). Commercial Paper • Commercial paper is a contract by which a borrower promises to pay a prespecified amount to the lender of the commercial paper at some date in the future, usually one to six months. • This prespecified amount is generally paid off by issuing new commercial paper (rollover). • Typically only available to very large companies with very high credit ratings. • These contracts are typically traded in public markets and carry very low interest rates. Corporate Bonds • Bonds are tradable fixed-income securities. • Always have a face amount of $1,000. • Nearly always have semi-annual coupon payments. – Coupon rate equals the sum of the two semi-annual payments divided by 1,000. – If the coupon rate is 6% the bond pays $30 every six months. The 6% represents (30+30)/1000. • Generally issued at with a coupon rate so that the bond sells for $1,000 in the open market. This is known as selling at “par.” • The initial coupon rate is typically set by the syndicate desk of the investment bank, which issues the bonds to its (largely institutional) clients. Deciphering Bond Quotes • Bond prices are quoted per $100 of face value (that is 1/10th of their true value). • A bond sells for par if its quoted price is 100. • A bond sells at a premium if its quoted price is above 100. • A bond sells at a discount if its quoted price is below 100. Quotes and Accrued Interest • Bond prices are quoted net of accrued interest. • Accrued interest is the amount of interest the current owner has “accrued” since the last coupon payment. • If the accrued interest on a bond is $4, and the quote is $98, then it will cost you $102 per $100 of face amount you buy. – In other words a single bond will run you $1,020. Calculating Accrued Interest • Corporate bonds accrue interest on a 30 day/360 day year rate. • Why? Because it has always been so. – Actually, due to the fact that bonds have been around a lot longer than the calculator. – Go ahead try to divided say 6.25 by 365 and then multiply by 14 by hand. Accrued Interest Calculation • Formula – Coupon payment of $C. – Last payment at date t0. – Today is date t. – Accrued Interest = C(t-t0)/180. • Note that half a year has only 180 days! What About the 5 or 6 “Extra” Days? • So you noticed a year has more than 360 days. What to do? • Since all months are assumed to have 30 days this means that the accrued interest on August 31 and September 1 will be the same. • Example: Bond pays coupons on January 15 and July 15. – On March 15 two months have passed and the accrued interest equals C(60/180). – Even February is assumed to have 30 days! On March 31 the accrued interest is C(75/180) and on April 1 it is C(75/180). Secondary Market in Corporate Bonds • The secondary market for corporate debt is largely a broker-dealer market. – Secondary market makers off to buy and sell particular bonds. – Quoted prices are better thought of as “ads” saying a dealer is here and ready to trade the bond. – To get a price at which you can trade you need to actually call the market maker. Yes, as in pick up a telephone and call. • A few corporate bonds are also traded on exchanges (see the New York Bond Exchange listing in the WSJ). But the market is limited to very small retail orders, generally of 10 bonds or less. • Most corporate bonds are not actively traded anywhere. Bond Covenants • Equity holders who control the firm can expropriate wealth from bondholders by making assets more risky, reducing assets through the payment of dividends, and adding liabilities. • Virtually all debt contracts contain covenants to restrict these kinds of activities: Asset Covenants • Seniority and collateral provisions ensure each debt instrument’s position in line should bankruptcy occur. – Senior debt must be paid in full prior to the junior debt receiving funds. Junior debt must be paid in full prior to the preferred shareholders. – Secured debt has a lien on a physical asset, the collateral. (Think car loan or home mortgage.) • If the firm does not pay the secured debt on time the debt holders can repossess the collateral. If selling the collateral does not pay the claim in full the secured debt holders become unsecured claimants for the remaining funds. • Their place on line, with the rest of the firm’s claimants, depends on the set of contract provisions. Dividend Covenants • Prevent the firm from effectively liquidating, handing the funds to the shareholders, and declaring bankruptcy. • Helps guarantee the bond holders receive their funds prior to the equity holders. Financing Covenants • Prevents the firm from issuing new debt that has seniority over the currently issued debt. – Not all debt has this protection! – On occasion investors have seen the value of their bonds plummet when a firm issues new debt that is either senior to or has parity with (a.k.a. pari passu) their bonds. Sinking Fund Covenants • Require that a certain portion of the bonds be retired before maturity. – A typical sinking fund on a 20-year bond might ensure that 24% of the bonds are retired between years 10 and 20. • The company must establish a bond sinking fund, which is to be used to meet the principal payment when the bond matures. – The cash is often deposited with an independent trustee. Theory: The Cost of Debt Financing 1. ANNOUNCEMENT EFFECTS – What is the information revealed by announcing a debt issue? 2. AGENCY COSTS – Debt in the capital structure induces a distortion of investment decisions (deviations from NPV rule). • • Reject projects with positive NPV Accept projects with negative NPV 3. BANKRUPTCY COSTS – What are the costs incurred in the process of resolving financial distress? Announcement Effects • Stock prices reaction to the announcement of a debt issue is as follows: – Non-bank debt: no impact. • Implies that such debt issues are neutral in terms of the information conveyed to the market. – Bank debt (renewal) positive: Equity value increases by about 1.9%. • Good news. The fact that the bank is willing to make a loan indicates that the firm’s prospects are better than the market previously thought. – Convertible debt: negative: Equity value decreases by about 2%. • Bad news. The issuance of this type of debt indicates the firm’s future prospects are not as good as the market previously believed. Agency Cost of Debt • When a firm has risky debt in its capital structure, maximization of shareholders’ value may differ from maximization of firm’s value (sum of equity and debt). – When evaluating a project, • shareholders emphasize its upside potential, • bondholders are concerned mainly with its downside risk, • from the point of view of the NPV you should look at both. $ Equity Payoff Debt Payoff Amount Promised Bond Holders Profits Risk Preferences • Notice that the equity holders like risk and the bond holders dislike risk. • Encourages management to select riskier projects, even if they have lower or perhaps negative present values. Example • Firm owes the bond holders $100. • The firm can invest in project Green or Gold. Each project costs $100 in PV to implement. • Project Green pays $101 in PV for sure. – This is a positive PV project with an expected profit of PV = $101-$100 = $1. • Project Gold pays $25 in PV half the time, and $125 half the time. – This is a negative PV project with an expected profit of .5($25)+.5($125) → PV = $75 - $100 = -$25. If Firm Maximizes Equity Value • Project Green – Firm earns $101. Equity gets $101 minus the amount owed debt ($100) for an expected profit of $1. • Project Gold – If the firm earns $25, it is bankrupt and the equity holders get zero. – If the firm earns $125, the bondholders collect the $100 due them. The equity holders get $125-$100 = $25. – Expected equity payoff equals .5($0) + .5($25) = $12.5. $ Equity Payoff Debt Payoff Expected Gold Payoffs High Gold Payoffs $100 Low Gold Payoffs Green Project Payoffs $100 Profits Intuition • For the equity holders: – Heads equity wins, tails debt loses. – If the firm does well the profits go to equity. – If the firm does poorly, the losses go to the bond holders. – For a given expected payoff, the more risk the better. What to Watch For • Project switching – Firm says it will pursue low risk cash flows in the future. – After issuing debt the firm switches to projects with high cash flow risks. • Empirical evidence – Only seems to be a problem when firms are close to or in bankruptcy. – Look for this in firms with low quality high yield debt or distressed debt. Bankruptcy Costs • If a firm is in financial distress, it may not be able to meet its debt obligations. – This may lead to default. • What are the possibilities? – Informal reorganization. Often called Workouts. • Bankruptcy – Formal reorganization (Chapter 11), or liquidation (Chapter 7). Why the Bankruptcy Code? • Why the government says we need a formal bankruptcy procedure: – To facilitate lending, creditors need legal rights to claim corporate assets. – To protect companies from excessive, inefficient liquidations. • Why we may not need the current structure: – In theory enforceable private contacts should allow lenders to claim assets. What is needed is an efficient mechanism for the verification of the lender’s claim followed by the swift transfer of assets. – Excessive and inefficient liquidations are unlikely in any setting. If the firm is worth more “alive than dead” the parties have every financial incentive to keep it going. It is more likely “excessive and inefficient liquidations” are political speak for “layoffs in my voting district.” – Current code often delays creditor’s claims, and makes contract provisions either totally unenforceable or effectively unenforceable. Bankruptcy Costs • Direct costs: – Legal and administrative costs; losses for forced liquidations • Indirect costs: – Lost business opportunities due to financial distress: • Lost customers • Suppliers want cash • Managers may leave • Why do shareholders care? – Because they can lose their stake in the firm – Because it makes debt much more expensive Tax Advantages of Debt Revisited • Tax deductibility of interest payments makes debt desirable at the corporate level. • What about personal taxes for investors? – Interest payments → typically taxed at the personal tax rate – Equity income → dividends taxes at personal rate capital gains taxed at lower rate • Overall, equity income is typically taxed at a lower rate. – Implication: after adjusting for risk, investors will require a higher return on debt than equity. • Tax advantage of debt at the corporate level. • Tax advantage of equity at the personal level. Implications for Capital Structure • Firms will want to use debt financing up to the point where they eliminate their entire corporate tax liabilities, but they will not want to borrow beyond that point. • With uncertainty, firms will pick the debt ratio that weighs the benefits associated with the debt tax shield, when it can be used, against the higher cost of debt increases where the debt tax shield cannot be used. • Firms with more non-debt tax shields are likely to use less debt financing. • There exists an optimal, firm-specific capital structure – Optimal debt level will: • Increase with expected cash flows • Decrease with risk of cash flows • Decrease with available deductions Firm Value Vmax D V High ACD Low ACE Low Tax Benefits optimal 1 D/V Low ACD High ACE High Tax Benefits Debt Policy In Practice • Most CFOs do not care about: – Taxes – Bankruptcy costs – Comparable firms • It seems that the most important factors that determine a firm's capital structure are: – Financial Flexibility – The cost of debt How D/E is Determined • Structure is more often changed by changes in the amount of equity, not in the amount of debt. – Since debt issues are infrequent relative to the daily revaluation of the stock in the marketplace. • The most important reasons why firms issue (repurchase) stock are: – Dilution in EPS, – Market under/overvaluation Equity – More or Less • Less: Share repurchases. – Stock prices react positively to the announcement of a share repurchase. – Cash payout: equivalent to dividends; – Signal of undervaluation • Methods: Tender Offers vs. Open Market Purchases – For Tender Offers: Average increase in the value of the firm’s stock equals 17%. Equity: More, New Issues • Stock prices tend to react negatively to the announcement of a new equity issue. – General cash offers occur after a significant run-up in an issuer’s secondary market price. • Announcement of an equity issue is met by a negative price reaction. – However, the negative price reaction tends to decrease during economic expansions. • Cancellation of an announced issue is met by a positive stock price reaction. • Frequency of equity issues tends to rise during economic expansions. Shelf Registration • To simplify the procedures for issuing securities, the SEC currently allows for “shelf registration.” – Firms with a stock value greater than $150 million can register stock or bonds, then issue them anytime in the next 2 years. • Allows management flexibility in when to issue securities (no waiting period between filing with the SEC and sale). • Asymmetric information period likely to be worse. – Probably why shelf registrations are used more for bonds than stocks • Firms do not have to name an investment banker in the registration statement. – Gives firm more leverage in bargaining wit investment bankers for lower fees. • Empirically, issuance costs are lower for shelf registered equity. Convertible Debt • A convertible bond gives the holder the right to exchange it for a given number of shares of stock anytime up to and including the maturity date of the bond. • If the holder chooses to convert, bondholders surrender their bonds in exchange for a given fraction of equity. – Example: Bond with $1000 face value – Convertible into equity @ $20 per share (conversion price) – Conversion ratio: 50 shares per bond • Conversion premium is the difference between the conversion price and the current stock price. • Convertible debt is sometimes callable. This means that the issuing firm has the option to convert (call for conversion) the bonds before maturity by paying a price specified in the contract. Convertible Bond Valuation • Includes: – The value of a Straight Bond – Option value • Holders of convertibles need not convert immediately. Instead, by waiting they can take advantage of whichever is greater in the future, the straight bond value or the conversion value. (This is call option for convertible bond holders) At maturity = Max (A, α, ET ) , A = bond’s face value ($1,000). α = conversion ratio. ET = stock price at maturity. Max A,α,ST = A + Value of the bond. A αMax 0,ST - α Value of the call option. Firm Options • Callable Bond – Firm has the option to call the bonds prior to maturity. – This is a call option for the firm. – Firms call bonds when: • Interest rates decline. • Their business fortunes improve. Call Provisions: Investment Grade Bonds • Often not callable. • If callable typical terms are “treasury yield plus 50 basis points.” – English translation: Discount the remaining cash flows at the treasury rate plus ½%. That is the call price. – Only pays to call such bonds if the bond can be refinanced at a spread smaller than 50 bps. • From the “Estimating the CAPM Inputs” lecture: Average yield spread between treasuries and AAA bonds is 52 bps. • Essentially call protected from changes in interest rates and most events involving the company’s fortunes. Call Provisions: High Yield Bonds • Typically callable. • Call schedule for a ten year bond often follows a pattern like the following if the coupon rate is C (example 12%): – In five years call at 100 + C/2 (106). – In six years call at 99 + C/2 (105). – In seven years call at 98 + C/2 (104). – Etc. High Yield Call Provisions • Call provision is a bet on both the company’s future fortunes and future interest rates. • If the company does well or interest rates fall substantially it will be able to issue new bonds at a substantially lower promised interest rate. – This will make calling the bonds attractive. – If paid in full the bond may be worth say 110 due to the high coupon rate and now promising company fortunes but can call it at just 106. Why Include Call Provisions • Signals that management believes the company will do much better in the future. • Call provision requires a higher initial coupon rate if the bond is issued at par (100). – Must compensate buyers for giving the firm the right to call the bond. • For the firm to recoup the higher initial cost it must do well enough in the future to make calling the bond worthwhile. What Firm Types Should Issue Callable Bonds? • If management knows the firm’s prospects are better than the market believes them to be then such firms should find callable bonds to be cost effective. – Pay more now, but know that with high probability will save later on. • For firms where management knows the firm’s prospects are no better than the market believes them to be, callable bonds should not be cost effective. – Pay more now, and later since with high probability it will never pay to call the bonds. Terminology: Yield to Call • Yield to Maturity (YTM) – Yield assuming it is never called. • Yield to First Call (YFC) – Yield assuming the bond is called at the earliest possible date. • Yield to Worst (YTW) sometimes Yield to Worst Call (YWC). – Yield assuming the bond is called on the date that produces the lowest yield for its owner. Quoting Convention • When bond traders quote yields, they typically quote yield to worst. – Assumption is that the firm in trying to minimize its cost of capital will end up calling the bond at the date that minimizes the bond’s yield. • Even YTW will, on average, overstate a bond’s expected return since it assumes all payments are made on time. – Some bond’s do not pay off on time reducing the expected return from the promised return. Callable Bond Yield Example • A bond pays semi-annual coupons of $6 per $100 of face value. The bond comes due in ten years. The call schedule is as follows: Year Call Price 6 106 7 105 8 104 9 103 Price Call Date Yield Relationship At Issue Price 6 Call Date 7 8 9 10 100 12.70% 12.47% 12.31% 12.19% 12.00% 105 11.54% 11.43% 11.35% 11.30% 11.16% 110 10.46% 10.45% 10.46% 10.47% 10.37% 115 9.44% 9.53% 9.61% 9.68% 9.63% YFC YTW YTM Key: Price Call Date Yield Relationship In Five Years Price 6 Call Date 7 8 9 10 100 17.75% 14.25% 13.13% 12.60% 12.00% 105 12.35% 11.43% 11.15% 11.04% 10.68% 110 7.34% 8.78% 9.29% 9.57% 9.44% 115 2.66% 6.29% 7.53% 8.18% 8.28% YFC YTW YTM Key: Price Call Date Yield Relationship In Seven Years Price Call Date 8 9 10 100 15.85% 13.36% 12.00% 105 10.50% 10.55% 10.03% 110 5.53% 7.91% 8.17% 115 0.89% 5.42% 6.42% Key: YFC YTW YTM Yield to Worst, Call Dates, and Time to Maturity • Because the call price is typically less than 100 + semi-annual coupon – Low market prices result in a Yield to Worst equal to the Yield to Maturity. – High market prices result in a Yield to Worst equal to the Yield to First Call. – As time progresses the price at which YTW switches from YTM to YFC declines. Why the Price YTW Pattern? • The tradeoff is the call price versus receiving the stream of semi-annual coupon payments. • Low market price + receiving the call price in the near future = very valuable relative to the future coupons. – Very high rate of return if you buy a bond for 100 and sell it six months later for 105. • High market price makes the return from receiving the call price much less attractive. In this case you want the future coupons. – Negative rate of return if you buy a bond for 106 and it is called six months later for 105. • As time passes the call price declines and the price at which the YTW equals the YTM declines with it. Debt Induced Problems • Having debt in the capital structure may induce shareholders to deviate from the NPV rule at later dates: – Shareholders may give up positive NPV projects (underinvestment problem). – Shareholders may take projects with negative NPV (excessive risk taking problem). • The cost of these inefficient investment policies is ultimately borne by the shareholders. • When issuing debt, shareholders must consider these costs as well, and trade them against the benefits of debt (such as its tax advantages) Debt vs. Equity • Share prices react negatively to announcements of equity issues, and positively to announcement of share buybacks. • The presence of asymmetric information may induce the firm to give up good investment opportunities. • Conflict of interest between short term and long term shareholders. • Issuing debt is better → Pecking Order Theory of Financing – Use retained earning first. – Then use securities that are less sensitive to informational asymmetries, such as senior debt. – Then use equity. • Value of financial slack. – If a good project comes along you want funds available to take advantage of it. Issuing debt so that you can no longer borrow may prevent a firm from making some beneficial investments. – Project financing may be helpful if it maintains some financial slack for the firm. Summary • OUTSIDE EQUITY – Costly because of its negative announcement effect. – Project financing may avoid such a negative impact. • DEBT FINANCING – Has positive effects: • Tax Advantages • No announcement effect • Reduces free cash-flow – Has negative effects: • Bankruptcy costs – Distortion of investment decisions: • Underinvestment. • Excessive risk taking. – Role for dividend constraints and bond covenants; – Use secured debt, convertible debt • RETAINED EARNINGS – Good: avoid costs of external financing – Bad: costs of free cash-flow