Management of Assaultive Behavior

advertisement

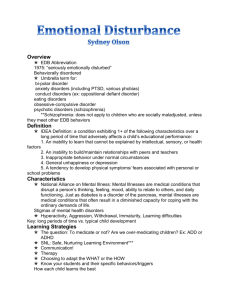

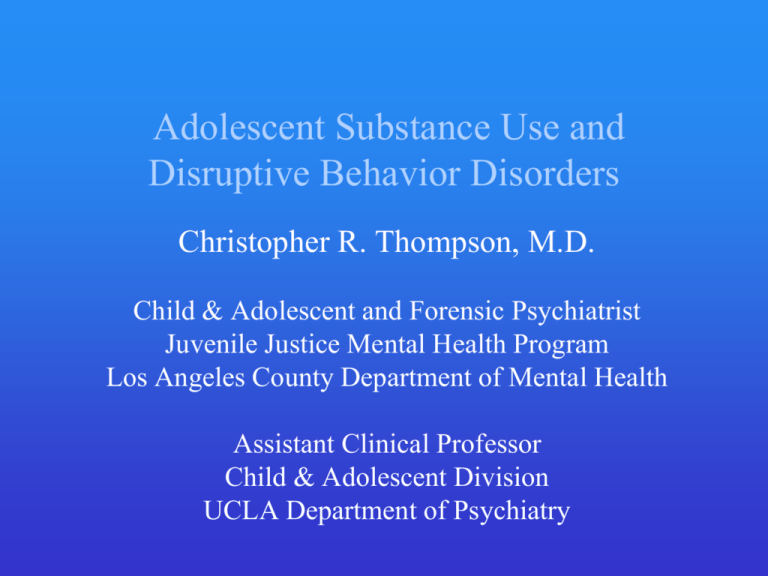

Adolescent Substance Use and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Christopher R. Thompson, M.D. Child & Adolescent and Forensic Psychiatrist Juvenile Justice Mental Health Program Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health Assistant Clinical Professor Child & Adolescent Division UCLA Department of Psychiatry Learning Objectives 1. To identify the rates of use/abuse/dependence in different groups of adolescents 2. To discuss briefly the diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) in adolescents 3. To identify disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) likely to co-exist with adolescent SUDs and discuss the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders in the context of SUDs 4. To explain special issues related to adolescent SUDs and the juvenile justice system 2 Definitions (1) • Teenager - Colloquial term generally meaning 13-19 year-old • Adolescent – Individual in the transition period between puberty and “full adulthood” or “full maturity” 1) Over the past 50-100 years, this period has generally lengthened considerably (e.g., increased need for higher education, individuals have married later, etc.) 2) Absence of single threshold distinguishing adolescence from adulthood in U.S. (e.g., different voting and drinking ages) 3) Brain not fully myelinated/pruned at least until mid 20’s, probably later 3 Definitions (2) • Minor - person who has not yet reached the age of majority (which is 18 in most states); minors can be emancipated or “mature” • Juvenile - person who has not yet reached the age at which s/he is treated as an adult by the criminal justice system (again, 18 is most states, but 14 or 16 y/o for some crimes); purview of juvenile justice can continue well after age of majority reached (e.g., DJJ-CDCR can hold “juveniles” until their 25th birthday; known in CA as “juvenile life”) 4 Adolescent Substance Use • Some substance use (i.e., experimentation) is normative for adolescents • Risk-taking and individuation are hallmarks of the adolescent period of development • Some evidence suggests that complete abstinence may be correlated with worse outcomes (e.g., poor social skills, more anxious, emotionally constricted, etc.) than experimentation (Shedler 1990) Shedler J, Block J. (1990). Adolescent drug use and psychological health. Am Psychol 45(5), 612-30. 5 Johnston LD, et al. (2007). Monitoring the Future: National Results on Adolescent Drug Use. Overview of Key Findings. Ann Arbor, MI. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Ctr. 6 Substance Abuse: DSM-IV Criteria Maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one or more of the following, occurring within a 12-month period: 1) Failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home 2) Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous 3) Recurrent substance-related legal problems 4) Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance 7 Substance Dependence: DSM-IV Criteria A maladaptive pattern of substance use, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by three (or more) of the following, occurring at any time in the same 12-month period: 1) Tolerance 2) Withdrawal 3) Using larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended 4) Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down 5) A great deal of time is spent in obtaining the substance, using, or recover from the substance’s effects 6) Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced 7) Continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problems caused by substance 8 Problems with DSM-IV • Does not inform about etiology or suggest treatment strategies • Diagnostic criteria not conceptualized within developmental framework; therefore, applicability questionable • Certain criteria inappropriate for adolescents 2^ to very low rate of occurrence (e.g., withdrawal symptoms) • Up to 30% of adolescents in SA treatment are “diagnostic orphans” (i.e., meet one or two criteria for Dependence, but none for Abuse) (Pollock 1999) Pollock NK Martin CS. (1999). Diagnostic orphans: adolescents with alcohol symptoms who do not qualify for DSM-IV abuse or dependence diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry 156(6), 897-901. 9 Rates of Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) in Adolescents (i.e., abuse or dependence) • Gen. Pop. (9-17 y/o): 2% (MECA Sample) • Gen. Pop. (14-17 y/o): 6% (MECA Sample) • W/ Psych. Disorders: 17% (MECA Sample) • In Juvenile Detention: 50% (Teplin 2002) • In MECA, 76% of individuals with a SUD also had a comorbid psychiatric disorder • Diagnosed by Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) 10 Gender Differences in Rates of Substance Dependence in 12-17 y/o’s • Caucasian (M vs. F): 2.9% vs. 2.8% • African-American: 3.2% vs. 1.7% • Hispanic: 4.9% vs. 3.0% • No gender differences observed when sample not divided by ethnicity • Based on NHSDA data from 1999 Summary of Findings from the 1999 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information, 2000. 11 General Signs of Adolescent SUDs (1) • Declining academic performance • Tardiness to school or outright truancy • Irritability/mood lability; aggressive outbursts • Giving up usual activities/hobbies • Change in peer group; hesitance to introduce new friends • Theft from family • Secretive behavior 12 General Signs of Adolescent SUDs (2) • Declining motivation • Forgetfulness • Change in sleeping habits • Depression, anxiety, etc. 13 Diagnosing Adolescent SUDs • Routinely asking about substance use history • Using screening instruments such as the CRAFFT (see next two slides) • More comprehensive instruments such as Adolescent Diagnostic Inventory (ADI), Substance Use/Abuse Scale from Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) or Teen Addiction Severity Index (T-ASI); • Drug Use Screening Inventory-Revised (DUSI-R) can identify youth at high risk for drug abuse and development of SUDs • Urine drug screen: remember the length metabolites stay in urine • Hair analysis 14 CRAFFT (1) 15 CRAFFT (2) Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. (2002). Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156(6), 607-14. 16 Are Clinical Impressions of Adolescent Substance Use Accurate? (Wilson 2004) • Study Compared clinicians’ assessments of substance use with validated, structured diagnostic interview (ADI) • 533 youth 14-18 y/o’s presenting to pediatric urgent care clinic for variety of reasons • Substance use rated as None, Minimal, Problem, Abuse, Dependence • 109 clinicians; composed of faculty (13%), fellows (7%), residents (63%), medical students (17%) Wilson CR, Sherritt L, Gates E, Knight JR. (2004). Are clinical impressions of adolescent substance use accurate? Pediatrics 114(5), e536-40. 17 18 Treatment of Adolescent SUDs (1) • • • Pharmacological: Very little data on effectiveness of agents such as naltrexone, disulfiram, acamprosate, etc. in adolescents (naltrexone had successful 6-week open label trial, n=5, in 2005) Psychological: Fairly good data for effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing/Enhancement (MI/MET), Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Parent Management Training (PMT), and various types of “family therapy” (e.g., Functional Family Therapy (FFT), Multi-Dimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) and Multisystemic Therapy (MST)); pilot data on Integrated Family CBT (IFCBT) showed promising results Little data on effectiveness of 12-step programs for adolescents, though these are generally encouraged 19 Treatment of Adolescent SUDs (2) • Consistently, best results achieved when parents or caregivers involved in treatment • PMT, FFT, MDFT, MST, and IFCBT necessarily involve family • School based treatments (e.g., DARE or Scared Straight) generally not effective and some even show harmful effects • Confidentiality issues may come into play (see later) 20 Psychiatric Disorders and SUDs (1) • Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception • Psychiatric disorder can precede or follow onset of SUD • Questions: 1) If psychiatric disorder precedes, does this lend credence to “self-medication” hypothesis? 2) If SUD comes first, does this mean that substance use caused psychiatric disorder (e.g., Substance-Induced Mood Disorder) or does it just unmask predilection? 3) Are these phenomena causal or just correlated? 21 Psychiatric Disorders and SUDs (2) • Abram et al (2003) surveyed 1829 youth aged 10-18 in the juvenile justice system and reported the following: 1) 25% reported that their major mental disorder (MMD) preceded their SUD(s) by > 1 year 2) 10% reported that their SUD(s) preceded their MMD by > 1 year 3) 65% developed their SUD(s) and MMD developed in the same year Abram KM, et al. (2003). Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60 (11), 1097-1108. 22 Psychiatric Disorders and SUDs (3) • In general population, most common disorders in children/adolescents are ADHD and anxiety disorders • Most frequent disorders comorbid with SUDs in children/adolescents are Conduct Disorder, ADHD, and Anxiety Disorders • Girls tend to have more internalizing disorders while boys have more externalizing disorders 23 Methodology for Epidemiology of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents (MECA) Data (1) • • • • • Anxiety Disorders Disruptive Disorders (including ADHD) Mood Disorders Substance Use Disorders Any Disorder • Rate is 11% if significant impairment required 13% 10% 6% 2% 21% Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. (1996). The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2.3 (DISC- 2.3): Description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA Study. Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35(7), 865–77. 24 MECA Data (2) 25 Diagnosing Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders (1) • Disruptive Behavior Disorders: ADHD, Conduct Disorder (CD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) • Anxiety Disorders: OCD, PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder, Separation Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Specific Phobia • Mood Disorders: Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, Substance Induced Mood D/O • Psychotic Disorders: relatively rare in this age group 26 Diagnosing Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders (2) • Clinical interview • Parent, caretaker, teacher, Probation/DCFS report • Rating scales (self report and others report) 1) Disruptive Disorders: SNAP-IV, Conners 2) Anxiety Disorders: SCARED, Liebowitz, CBCL, etc. 3) Mood Disorders: CDI, HAM-D, CBCL Active substance use complicates process 27 Disruptive Behavior Disorders and SUDs (1) • ADHD, CD, and, to some extent, ODD are overrepresented in individuals with SUDs in both children and adolescents (e.g., 35-71% of adult alcoholics had childhood-onset and persistent ADHD; Wilens 2004) • Converse also true; that is, individuals with ADHD, CD are more likely to have SUDs (e.g., 17-45% of ADHD adults have EtOH abuse/dependence and 930% have drug abuse/dependence; Wilens 1995) Wilens T. (2004). ADHD and the substance use disorders: the nature of the relationship, who is at risk, and treatment issues. Prim Psychiatry 11, 63-70. Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J. (1995). Are attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the psychoactive substance use disorders really related? Harv Rev Psychiatry 3(3), 160-2. 28 Disruptive Behavior Disorders and SUDs (2) • Both ADHD and CD are risk factors for SUDs, but latter greater OR; cumulative effects • High rate of comorbid SUDs likely multifactorial (inherent novelty-seeking (?DA deficiency) in both Conduct Disorder and ADHD, school failure leading to assoc. w/ anti-social peers, etc.) • Treatment of ADHD does not exacerbate SUDs (e.g., craving) and is likely protective against development of SUDs in adolescence (see later slides) 29 Treating Comorbid Disruptive Behavior Disorders (1) • Pharmacological and/or psychological interventions have shown efficacy for certain disorders (e.g., ADHD) • Former more likely to be employed in primary care settings • Need to be familiar with treatments/interventions available and the evidence supporting use 30 Treating Comorbid Disruptive Behavior Disorders (2) • ADHD: Stimulants can be first-line treatment in many cases; excellent evidence for use; scores, if not hundreds of RCTs; atomoxetine (Strattera) also useful; behavioral therapy can be helpful adjunct • Conduct Disorder: Little evidence to support pharmacological treatments (perhaps atypicals effective for txing aggression assoc. w/ CD); MST, PMT, CBT show most promise • Oppositional Defiant Disorder: PMT, perhaps CBT/anger mgmt. (e.g., STAR) 31 ADHD (1) • Base rate in population around 5-8% • 2.5x higher rate in boys • General domains include hyperactivity, impulsivity, and ↓attention/concentration • Children/adolescents with ADHD, Inattentive Type are likely to be diagnosed later 32 33 ADHD (2): Stimulants • Stimulants most effective treatment (effect sizes 1.01.3 for stimulants vs. 0.6-0.7 for atomoxetine) • Excellent data for use • Quick onset of action • Excellent safety profile • Limited side effects including no significant longterm side effects (? ↓ adult height w/ post-hoc analysis of MTA data) 34 Conduct Disorder and ADHD: Stimulant Misuse, Abuse and Diversion • Conduct Disorder Domains 1) Aggression to people or animals 2) Destruction of property 3) Deceitfulness or theft 4) Serious violations of rules • Some risk of misuse/abuse/diversion with ADHD patients, but magnified with comorbid SUDs and Conduct Disorder (see later slides) 35 Definitions Misuse: Medication used in a manner in which it was not prescribed Abuse: Meets DSM-IV TR criteria for abuse (see previous slide) Diversion: Transfer of medication from the patient to another person for any purpose, such as performance enhancement or recreational use The term nonmedical use can be used to describe all of the above. 36 Rates of Diversion of Stimulants among Canadian HS Students • 13,549 students sampled; 5.3% on Rxed stimulants • 14.7% of these gave meds to others • 7.3% sold meds to others • 4.3% had their meds stolen • 3.0% were forced to give up their meds Poulin C. (2001). Medical and nonmedical stimulant use among adolescents: from sanctioned to unsanctioned use. Canadian Medical Association Journal 165 (8), 1039-44. 37 Rates of Non-Medical Use of Stimulants among U.S. College Students (1) • 10,904 students sampled • 6.9% lifetime prevalence of non-medical Rx stimulant use • 4.1% past year prevalence • 2.1% past month prevalence • Rates ranged from 0-25% at individual colleges McCabe SE. (2005). Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction 100(1), 96-106. 38 39 Rates of Non-Medical Use of Stimulants among U.S. College Students (2) • Increased rates of abuse/diversion if: 1) Male 2) White 3) Member of fraternity or sorority 4) Lower grades 5) College in Northeast with highly-competitive admissions standards 40 Characteristics of Adolescents with ADHD Who Divert or Misuse Rxed Stimulant Meds • Part of 10-year longitudinal study; 55 ADHD subjects, 43 controls (receiving meds for other purposes) • 11% of ADHD subjects sold medications • 22% misused medications • Of those who misused medications, 83% had SUD or CD • IR formulations most often reported diverted Wilens TE, et al. (2006). Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45(4), 408-14. 41 Minimizing Stimulant Abuse and Diversion in ADHD Treatment 1) Know your patient’s demographics and history 2) Long-acting preparations generally abused less 3) Open capsules and mix (e.g., Adderall XR, Focalin XR); prevents attempts at intranasal use/injection 4) Utilize new preparations (e.g., MPH patch (Daytrana), new AMP prep. lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) 5) When feasible, enlist parents help in dispensing meds/counting pills 42 Daytrana (MPH Patch) • Approved by FDA in 2006 • 10, 15, 20, 30 mg patches (amount delivered over 9 hours), but each patch actually contains 2.75x the listed amount of MPH • Can deliver up to 15 hours of coverage, but generally worn for 9 hours (effects may last 2-3 hours after removing) • Somewhat slower onset of action than other long-acting stimulant preparations • After 4-5 weeks, plasma levels may be double of equivalent dose of oral MPH and dose of medication my need to be reduced (more efficient delivery) 43 Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) • Approved by FDA in 2007, in pharmacies July 2007 • “Pro-drug” that has an L-lysine attached to Damphetamine; biologically inactive until undergoes first pass metabolism in small intestine/liver (hydrolysis) • Less abuse potential: longer acting, lower “likeability rating” than DEX, biologically inactive if snorted or used IV • Comes in 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 mg doses (initially 30, 50, 70 mg but titration was difficult) • Lis-DEX 25 mg = DEX 10 mg 44 Dosing Rules of Thumb • Shoot for @ 1 mg/kg for: lisdexamfetamine, MPH products • Shoot for @ 0.5 mg/kg for: amphetamine-based products and dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) • Shoot for @ 1.2 mg/kg for atomoxetine (Strattera) • For stimulants, titrate up to target dose over 2-3 weeks • Can go higher if needed and side effects not problematic; underdosing probably more prevalent that overdosing 45 Pharmacotherapy of ADHD Reduces Risk for SUD (Biederman 1999) Biederman J, et al. (1999). Pharmacotherapy for ADHD reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 104(2), e20. 46 Pharmacotherapy of ADHD Reduces Risk for SUD: Four year follow-up (Biederman 2003) • Original cohort re-examined four years later • Unmedicated ADHD (n=19), Medicated ADHD (n=56), Control (n=137) • Rates of SUDs were: 1) Unmedicated ADHD: 75% 2) Medicated ADHD: 25% 3) Controls: 20% Biederman J. (2003). Pharmacotherapy for ADHD decreases the risk for substance abuse: Findings from a longitudinal follow-up of youths with and without ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry 64(suppl. 11), 3-8. 47 Stimulant Therapy and Risk for SUDs in Adulthood (1) • Original cohort re-examined ten years later • No protective effect of stimulant treatment against SUDs found in adulthood • Consistent with Wilens finding from meta-analyis that stimulant-treated subjects were 5.8x less likely to have SUDs in adolescence, but only 1.4x less likely in adulthood (Wilens 2003) • Only 22% were on stimulant treatment at time of reassessment Biederman J, et al. (2008). Stimulant therapy and risk for subsequent substance use disorders in male adults with ADHD: a naturalistic controlled 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 165(5): 597-603. Wilens TE, et al. (2003). Does stimulant therapy of ADHD beget later substance abuse? A meta-analytic review of the literature. Pediatrics 111(1): 179-85. 48 Stimulant Therapy and Risk for SUDs in Adulthood (2) Hypotheses: • Parental monitoring and therefore treatment compliance better in childhood/adolescence • Stimulant treatment may delay rather than prevent SUDs (i.e., adolescents had not yet fully passed through “risk period to develop SUDs) • Therefore, continued stimulant treatment may be necessary to reduce risk of SUDs in adulthood 49 Age of Initiation of Stimulant Treatment and Development of SUDs • 176 MPH-treated Caucasian male children aged 6-12 w/ ADHD but w/o CD • Followed up in late adolescence (mean age=18.4 years) and adulthood (mean age=25.3 years) • Subjects with late initiation of stimulant treatment (i.e., at age 8 or later) had higher rates of non-EtOH SUDs and ASPD in adulthood • Subjects with early initiation of stimulant treatment did not differ from controls w/r/t rates of SUDs or ASPD Mannuzza S, et al. (2008). Age of methylphenidate treatment initiation in children with ADHD and later substance abuse: prospective follow-up into adulthood. Am J Psychiatry 165(5): 604-9. 50 Prevalence of Mental Disorders in the Juvenile Justice System (1) • Approximately 66% of juvenile pre-trial detainees or delinquents meet DSM-IV criteria for a mental disorder: 1) Includes substance abuse/dependence and Conduct Disorder (Grisso 2004) 2) Excluding Conduct Disorder alone as a mental disorder decreases rates by only approx. 5% Grisso T. (2004). Double Jeopardy: Adolescent Offenders with Mental Disorders. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 51 Prevalence of Mental Disorders in the Juvenile Justice System (2) • • • • • • • • • Conduct Disorder ADHD Substance Abuse Personality Disorders Mental Retardation Learning Disorders Mood Disorders Anxiety Disorders Psychoses & Autism 50 – 90% 19 – 46% 25 – 50% 02 – 17% 07 – 15% 17 – 53% 32 – 78% 06 – 41% 01 – 06% Otto R, Greenstein J, Johnson M, Friedman R. (1992). Prevalence of mental disorders among youth in the juvenile justice system. In J. Cocozza (Ed.), Responding to the mental health needs of youth in the juvenile system (pp. 7-48). Seattle: National Coalition for the Mentally Ill in the Criminal Justice System. 52 Psychiatric Disorders in Youth In Juvenile Detention (Teplin 2002) Teplin LA, et al. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59(12): 1133-43. 53 Prevalence of Mental Disorders in the Juvenile Justice System (3) • Rates of all disorders higher than that of the general population; the “big three” are Conduct Disorder, ADHD, and Substance Abuse/Dependence • Higher rates of Learning Disorders (17-53%), Mental Retardation (7-15%), and generally lower intelligence levels in juvenile delinquents 54 The Performance of Incarcerated Juveniles on the MacCAT-CA WISC-III (or WAIS-III)/WRAT Ages 9-12 13-14 15-16 17-18 IQ 73.7 74.3 72.6 87.6 Reading 73.0 81.6 82.7 83.4 Spelling 78.6 82.3 84.4 83.9 Math 77.2 80.0 83.0 85.4 Ficke SL, Hart KJ, Deardorff PA. (2006). The performance of incarcerated juveniles on the MacCAT-CA. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 34(3), 360-73. 55 Prevalence of Mental Disorders in the Juvenile Justice System (4) • Also more likely to have these risk factors, which may increase risk of SUDs: 1) Pre-natal exposure to drugs or alcohol 2) Attachment problems arising in infancy 3) Exposure to trauma (violence, abuse, etc.), even if exposure does not cause PTSD 4) Dysfunctional and chaotic families and neighborhoods 5) Overcrowded schools with limited resources 6) lower intelligence 56 Additional Options in Juvenile Justice System Pre-adjudication (i.e., diversion) (1) • “Drug” Court: Minors with drug-related charges or significant substance use problems. Generally orders substance abuse treatment either on outpatient or residential basis. Typically, random UTS mandatory. • Mental Health Court (e.g., Dept. 203 in Los Angeles County): Handles minors with severe mental disorders; comorbid SUDs common 57 Additional Options in Juvenile Justice System Post-adjudication (2) 1. Mandatory mental health treatment in the community: Can include residential placement, medication follow-up, different therapy modalities (including MST, SUDs treatment), wraparound services 2. Probation Camp System: Minors serve 3-, 6-, or 9month sentences (being increased to 5-7 and 7-9 month sentences); mental health services and SUDs treatment offered 58 L.A. County Probation Dept. Camp System (1) • Approximately 20 camps in outlying areas of Los Angeles County • Camps currently undergoing re-design with focus on reducing recidivism and involving parents in treatment • SUDs targeted because of strong link to recidivism • “Evidence-based practices” for SUDs (among other disorders) are being implemented (e.g., MET/MI, IFCBT, PMT, CBT, etc.) 59 L.A. County Probation Dept. Camp System (2) • Camps Assessment Unit: being phased in at Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall to provide more comprehensive psychiatric and educational evaluations of minors (including evaluating for SUDs); ensures minors are being directed to the most appropriate camp or other placement; may use CRAFFT, ADI vs. TASI • Camp Holton: Assuming role as camp dedicated to treating minors with “co-occurring” disorders • MST: being implemented on release to decrease risk of continued anti-social behavior and substance use 60 L.A. County Probation Dept. Camp System (3) • Strong focus on other aftercare options and fostering linkages to community resources • Numerous additional funding sources (MIOCR grant, MHSA funds) have helped with these initiatives • Numerous outcome variables will be tracked 61 Case Example (1) • 17 y/o WM, high SES, w/ long history of tic disorder, ADHD, MDD, LD, and SUDs (Rx stimulants (snorted D-MPH), MJ, cocaine, EtOH) and numerous trials of various ADHD medications from age six (MPH, AMP products, atomoxetine, clonidine, guanfacine, bupropion XL) with varying degrees of success at varying times • SUDs problematic enough that spent 18 months at RTF in Utah; now back in Los Angeles; has GED, will be attending college in seven months; working at coffee shop; attending AA/NA meetings daily 62 Case example (2) • At time of first appt., on BPPXL 450 mg/day, aripiprazole 20 mg/day, atomoxetine 120 mg/day; still with significant ADHD sxs (primarily inattentive domain) impairing work functioning and, to some extent, impairing fxing at home w/r/t rel. with parents • What do you do next? What are pros and cons of different treatments? 63 Case example (3) • Options include: 1) Daytrana or 2) Lisdexamfetamine and 3) Parental monitoring/pill count • Ended up using lisdexamfetamine and titrated to 70 mg/day; pt. advised re: lack of biological activity if used intra-nasally or IV • Pt. still ended up attempting to snort large quantities of lisdex.; currently in Betty Ford completing 90-day inpt. program 64 Take Home Points 1. Make sure to screen for SUDs in adolescents in a systematic manner (e.g., CRAFFT) 2. Make sure to screen for and treat psychiatric disorders (or refer for treatment); doing so can lower the chance of a SUD developing/persisting (particularly treating ADHD) 3. Remember that there is good empirical support for a variety of psychotherapeutic modalities in treating adolescent SUDs; data on pharmacological treatments (e.g., naltrexone) is much more limited 65 Additional Suggested Reading • Tarter RE. (2002). Etiology of adolescent substance abuse: A developmental perspective. Am J Addict 11(3), 171-91. • Tarter RE, Kirisci L. (2001). Validity of the Drug Use Screening Inventory for predicting DSM-III-R substance use disorders. J Child Adol Subst Abuse 10, 45-53. 66