Facts

advertisement

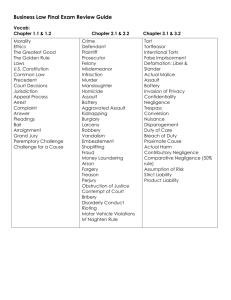

Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Responses to Harm ..............................................................................................................................................6 1.2 Identifying Those Responsible for Harm ............................................................................................................6 1.2.1 Joint Tortfeasors (60, 63-64) ........................................................................................................ 6 1.2.2 Vicarious Liability (344-357)......................................................................................................... 6 1.2.3 Joint and Several Liability ............................................................................................................. 8 1.2.4 Victim Contribution (Contributory negligence) ........................................................................... 8 2. Negligence ................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Duty of Care ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2.1 Origins of Duty of Care ............................................................................................................... 10 2.2.2 The Current Approach to Duty ................................................................................................... 11 2.2.3 Examples of Proximity ................................................................................................................ 12 2.2.4 The Duty to Warn ....................................................................................................................... 14 2.2.5 Medical Malpractice .................................................................................................................. 14 2.2.6 Rescuers and Good Samaritan ................................................................................................... 15 2.3 Standard of Care ................................................................................................................................................ 15 2.3.1 Unreasonable Risk...................................................................................................................... 15 2.3.2 The Learned Hand Formula........................................................................................................ 15 2.3.3 Indices of Reasonableness ......................................................................................................... 16 2.3.4 Departure from Custom ............................................................................................................. 16 2.3.5 Statutory Standards ................................................................................................................... 16 2.3.6. Professional Standards ............................................................................................................. 17 2.3.7 Determining Reasonable Behaviour .......................................................................................... 17 2.3.8 Special Standards: Children and the Mentally Ill ....................................................................... 17 2.4 Causation ........................................................................................................................................................... 18 2.4.1 The ‘But For’ Test ....................................................................................................................... 18 2.4.2 The Difficulty of Proof ................................................................................................................ 18 2.4.3 Multiple Wrongdoers and Contribution ................................................................................... 18 2.4.4 Inadequate Supreme Court Analysis.......................................................................................... 19 2.4.5 Failure to Warn and Causation .................................................................................................. 19 2.4.6 Lost Chances and Medical Malpractice...................................................................................... 19 2.4.7 Causation and Industrial Torts: The English and US Experiments: ........................................... 20 Table of Contents 2.5 Remoteness ........................................................................................................................................................ 20 2.5.1 The Thin Skull Rule ..................................................................................................................... 21 2.5.2 Novus Actus Interveniens .......................................................................................................... 21 2.5.3 Manufacturers, Distributors, Contractors and Remoteness ...................................................... 21 2.5.4 Multiple Medical Errors ............................................................................................................. 22 2.6 Defences to Negligence Actions ........................................................................................................................ 22 3. Liability for Psychiatric Harm (Nervous Shock)............................................................................... 24 3.1 Historical Development of the Law ................................................................................................................... 24 4. Liability for Pure Economic Loss .................................................................................................... 25 4.1 Recognized Categories ...................................................................................................................................... 25 4.2 Negligent Misrepresentation .............................................................................................................................. 25 4.3 Negligent Provision of a Service .................................................................................................... 26 4.5 New Categories ............................................................................................................................. 27 5. The Tort Liability of Government ....................................................................................................................... 29 6. The Immunity of Mothers .................................................................................................................................... 31 7. Negligence and Reproduction .............................................................................................................................. 32 Table of Cases Cook v. Lewis (SCC 1951) ...................................................................................................................6 671122 v. Sagaz industries Canada Inc. () ............................................................................................7 Bazley v. Curry (SCC 1999) ..................................................................................................................7 E.B. v. Order of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in the Province of British Columbia (SCC 2005) ..........7 Yepremian v. Scarborough General Hospital (OCA 1980) .....................................................................8 Jaman Estate v. Hussain (2002) ...........................................................................................................8 BG Checo International Ltd. v. British Columbian Hydro and Power Authority (SCC 1993) .................. 10 Mitchell v. Allestry (1676) ................................................................................................................ 10 Palsgraf v. The Long Island Railroad Co. (NY CA 1928) ....................................................................... 11 Dooghue v. Stevenson (House of Lords 1932).................................................................................... 11 Home Office (defendant) v. Dorset Yacht Company (plaintiff) (House of Lords 1970)......................... 11 Kamloops (City) v. Nielson (SCC 1984) ............................................................................................... 11 Cooper v. Hobart (SCC 2001)............................................................................................................. 11 Jordan House Ltd. v. Menow (SCC 1973) ........................................................................................... 12 Odhavji Estate v. Woodhouse (SCC 2003).......................................................................................... 12 Crocker v. Sundance Northwest Resorts (SCC 1988) .......................................................................... 12 Stewart v. Pettie (SCC 1995) ............................................................................................................. 13 Childs v. Desormeaux (SCC 2006) ...................................................................................................... 13 Hollis v. Dow Corning Corporation (SCC 1995) ................................................................................... 14 Reibl v. Hughes (SCC 1980) ............................................................................................................... 14 Videto et al. v. Kennedy (Ont. C.A. 1981) .......................................................................................... 14 Brito (Guardian ad litem of) v. Woolley (BCCA 2003) ......................................................................... 14 Van Mol (Guardian ad Litem of) v. Ashmore (BCCA 1999) .................................................................. 15 Horsley (Next friend of) v. MacLaren (SCC 1971) ............................................................................... 15 Bolton & Others v. Stone (England 1951) .......................................................................................... 15 Paris v. Stepney Borough Council (England 1951) .............................................................................. 15 Rentway Canada Ltd. v. Laidlaw Trasnport Ltd. (Ont. C.A. 1989) ........................................................ 15 Watt v. Hertfordshire (England 1954) ............................................................................................... 15 Warren v. Camrose (City) (AB C.A. 1989) ........................................................................................... 16 Waldick v. Malcolm (SCC 1991) ......................................................................................................... 16 Brown v. Rolls Royce (? 1960) ........................................................................................................... 16 Canada v. Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SCC 1983) .............................................................................. 16 Table of Cases Gorris v. Scott (Exchequer 1874) ....................................................................................................... 16 Ryan v. Victoria (City) (SCC 1991) ...................................................................................................... 16 Brenner et. al. v. Gregory et. al.(O.R. 1973) ....................................................................................... 17 ter Neuzen v. Korn (SCC 1995) .......................................................................................................... 17 Vaughan v. Menlove (England 1837) ................................................................................................. 17 Heisler et al. v. Moke et al. (Ont. H.C. 1971) ...................................................................................... 17 Pope v. RGC Management (AB QB 2002) ........................................................................................... 17 Nespolon v. Alford et al. (Ont C.A. 1998)........................................................................................... 17 Fiala v. Cechmanek (AB C.A. 2001) .................................................................................................... 18 Athey v. Leonati (SCC 1996) .............................................................................................................. 18 Snell v. Farrell (SCC 1990) ................................................................................................................. 18 Cook v. Lewis (SCC 1951) .................................................................................................................. 18 B.M. v. British Columbia (Attorney General) (BCCA 2004) .................................................................. 18 Resurfice Corp. v. Hanke (SCC 2007) ................................................................................................. 19 Walker Estate v. York Finch General Hospital (SCC 2001) ................................................................... 19 Martin v. Capital Health Authority (ABQB 2007) ............................................................................... 19 Chester v. Afshar (UKHR 2004) ......................................................................................................... 19 Laferrier v. Lawson (SCC 1991) .......................................................................................................... 19 Barker v. Corus UK Ltd, (UKHL 2006) ................................................................................................. 20 Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories (US) ................................................................................................... 20 Overseas Tankship Ltd. v. Morts Dock & Engineering Company(The Wagon Mound No. 1)(UKPC 1961) ........................................................................................................................................................ 20 Hughes v. Lord Advocate (HL 1963)................................................................................................... 20 Assiniboine School Division No. 3 v. Hoffer (Man. C.A. 1971) ............................................................ 20 Lauritzen v. Barstead (Alta S.C. 1965) ............................................................................................... 21 Bishop v. Art & Letters Club of Toronto et al. (Ont. H.C. 1978) ........................................................... 21 Athey. v. Leonati (SCC 1996) ............................................................................................................. 21 Bradford v. Kanellos (c.o.b. Astor Delicatessen & Steak House)(SCC 1974) ......................................... 21 Smith v. Inglis Lts. (? 1978) ............................................................................................................... 21 Good-Wear Treaders Ltd. v. D & B Holdings Ltd. et al. (N.S. C.A. 1979)............................................... 22 Stansbie v. Troman (? 1948) ............................................................................................................. 22 Mercer v. Gray (Ont. C.A. 1941) ........................................................................................................ 22 Table of Cases Katzman v. Taeck (Ont. C.A. 1982) .................................................................................................... 22 Devji v. Burnaby (District) (BCCA 1999) ............................................................................................. 24 Mustapha v. Culligan of Canada Ltd. (SCC 2008) ................................................................................ 24 Hedley Byrne & Co. Ltd. v. Heller & Partners Ltd. (HL 1964) ............................................................... 25 BG Checo International Ltd. v. British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (SCC 1993) .................... 25 Hercules Managements Ltd. v. Ernst & Young (SCC 1997) .................................................................. 26 Avco Financial Services Realty Ltd. V. Norman (Ont. C.A. 2003) ......................................................... 26 Haskett v. Equifax Canada Inc. et al. (Ont. C.A. 2003) ........................................................................ 26 Wilhelm v. Hickson (? 2000) ............................................................................................................. 26 B.D.C. Ltd. v. Hofstrand Farms Ltd (SCC 1986) ................................................................................... 27 Winnipeg Condominium Corporation No. 36 v. Bird Construction Co. (SCC 1995) ............................... 27 M. Hasegawa & Co. v. Pepsi Bottling Group (Canada), Co. (BCCA 2002) ............................................. 27 Design Services Ltd. v. Canada (SCC 2008) ......................................................................................... 28 Kamloops (City) v. Nielson (SCC 1984) ............................................................................................... 29 Just v. British Columbia (SCC 1989) ................................................................................................... 29 Cooper v. Hobart (SCC 2001)............................................................................................................. 29 Hill. V. Hamilton-Wentworht Regional Police Services Board (SCC 2007) ............................................ 30 Dobson (Litigation Guardian of ) v. Dobson (SCC 1999) ...................................................................... 31 Preston v. Chow (2002 Man. C.A.) .................................................................................................... 31 Paxton v. Ramji (Ont. C.A. 2008) ...................................................................................................... 32 Ediger (Guardian ad litem of) v. Johnston (BCSC 2009) ...................................................................... 32 Norberg v. Wynrib (SCC 1992) .......................................................................................................... 33 Non-Marine Underwriters v. Scalera (SCC 2000)................................................................................ 33 Introduction 1. Introduction 1.1 Responses to Harm Tort law concerns individually compensable wrongs. Wrongs can be intentional or unintentional. Tort laws do not depend on contractual relationships, or even any prior relationship between the parties (e.g. car accident). There is not singular theory of tort law justification, nor a theory of where it is going. Tort law is fault based. Who can be found liable in tort law? Natural or 'juristic' persons (e.g. corporations, occasionally government) 1.2 Identifying Those Responsible for Harm 1.2.1 Joint Tortfeasors (60, 63-64) Joint tortfeasors are people involved in common tortious action, though only one of them need have committed the actual tort. Requires a special relationship between tortfeasors: 1. One instigates/encourages another to commit tort 2. Employer/Employee in scope of employment 3. Principal/Agent 4. Guilt by Participation (specific to fact pattern) If the relationship holds, proof of tortious action against one establishes liability to all (joint and several liability—each Δ is liable for full damages, though courts now apportion blame for ease of future lawsuits) Cook v. Lewis (SCC 1951) Note:(Cook=appellant, Lewis=plaintiff) Issues: In the case that fault cannot be assigned, can damages be awarded? Facts: Ratio: Cook and others were hunting and had agreed to share their kills. Cook and other fired at roughly the same time, and Lewis was shot in the eye. Jury could not determine who fired the shot that hurt Lewis, and trial judge dismissed the action Appeal judge rejected the notion that they were joint tortfeasors When one of two parties is certain to have committed the tort, but it cannot be decided which one, then neither can be responsible. People joined in lawful pursuits with no reason to expect negligence and no opportunity to control others are not jointly responsible. 1.2.2 Vicarious Liability (344-357) 1. Vicarious liability is policy based, giving the π an alternative, potentially more solvent Δ. It is a strict liability (requires no proof of wrongdoing by vicarious party, only requisite relationship) Key to a tortfeasor is establishing the proper relationship between tortfeasor and vicarious party. Employee/Employer relationship Policy concerns: o Practical remedies to π Employers take benefit, thus should absorb losses created Introduction o Employers are in a better position to pay judgments. Employers can better spread the loss. Deterrence of future harm employer can select, train, and control employees to minimize risks. Test for vicarious liability: 1. Is there a requisite relationship? (Sagaz) If no, there is no vicarious liability. If yes, go to b. 2. Was the tort committed in the course of employment? (E.B.) Requisite Relationship: Employees are different from independent contractors (Sagaz). Independent contractors do not give rise to vicarious liability. Control test to differentiate: (inadequate) Does the employer exercise sufficient control over the employee/contractor? 671122 v. Sagaz industries Canada Inc. () Facts: Held: Ratio: A consultant for an automotive supplier bribed a Canadian Tire employee to win the contract for the supplier. Consultant was in business for himself, thus Canadian Tire was not vicariously liable. Functional Test to differentiate employees from independent contractors Is the "person in business on his own account"? Consider these factors (not exhaustive) Control test Who provides equipment? Who hires helpers? Financial risk? Degree of responsibility over investment/management Opportunity for profit? Course of Employment Bazley v. Curry (SCC 1999) Ratio: Vicarious liability holds when: a. An employee performs an act authorized by the employer b. The act is connected to an authorized act such that it is a mode (even if improper mode) of doing the act. To justify vicarious liability, a court should see (1) if precedent unambiguously determines if vicarious liability holds. If not, (2) strict liability policy rationale will determine if vicarious liability is appropriate. Factors to Assess whether employer enhanced risk of employee tort 1. opportunity to abuse power 2. extent act may further aims of employer 3. relation to friction, confrontation, or intimacy inherent to enterprise 4. power conferred over victim 5. vulnerability of potential victims E.B. v. Order of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in the Province of British Columbia (SCC 2005) Introduction Notes on the Liability of Doctors: Yepremian v. Scarborough General Hospital (OCA 1980) 3:2 decision: Hospitals do not have a non-delegable duty towards patients in relation to doctors with hospital privileges. In other words, hospitals are not vicariously liable for doctors with hospital privileges. Jaman Estate v. Hussain (2002) Vicarious Liability Might be appropriate for Hospitals when the patient has no choice of doctor (e.g. emergency care). Policy considerations: 1. Public relies on hospitals and and typically cannot question competence of staff. 2. Patients cannot discern employees from those with privileges. It is unfair to ask patients to sort this out when bringing an action. Presentation at hospital=should be able to sue hospital. Parents are not vicariously liable in common law, but sometimes by statute for intentional property damages. 1.2.3 Joint and Several Liability Several liability (separately [individually] liable) Multiple tortfeasors causing indivisible damage are joint tortfeasors or several concurrent tortfeasors. If there is contributory negligence, the π must collect from each individually (only severally liable). Negligence Act: (BC) By this act, Δ's are made jointly and severally liable. 4.2(a) More than one defendant joint and severally liable can be individually responsible for the global damages awarded. 4.2(b) Where one party pays the global damages, that party can collect or bring an action to collect against the other liable party or parties. Contributory negligence: unreasonable conduct by π that contributes to the damages. Initially, contributory negligence was a complete defense. To address injustices, the "last clear chance" rule was implemented, giving judges some discretion. 1.2.4 Victim Contribution (Contributory negligence) Contributory negligence is a partial defence against a negligence claim. Contributory negligence is the failure of a plaintiff to take reasonable care for his own safety, which contributes to the harm. Rule of Last clear chance: if the defendant had the last clear chance to avoid the incident, he is wholly responsible for it. Now, legislation apportions losses. Default is 50% when courts cannot determine relative degrees of blameworthiness. 3 Sorts of Contributory Negligence: 1. Plaintiff negligence causes accident 2. Plaintiff negligence does not cause accident, but places the plaintiff in the position of foreseeable harm from Δ’s negligence. 3. Plaintiff fails to take protective measures in the face of foreseeable dangers. Determined by the objective standard of the reasonably prudent person. Considered factors include: 1. Foreseeability of harm 2. Likelihood of damage 3. Seriousness of threatened damage 4. Cost of precautionary measures 5. Exigent circumstances Introduction 6. Utility of π conduct. (i.e. police officers) Courts tend to give small reductions (up to 30%) in most cases. Negligence Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 333 s. 1: liability is apportioned by fault; where fault cannot be determined, liability is apportioned equally between parties. s. 2: damage is in $, and liability in %; π can claim % apportioned to each party; Negligence: Duty of Care 2. Negligence 2.1 Introduction Developed from “trespass on the case” to cover broader claims. Elements of a Negligence Action: (in addition to damages above diminimus) 1. Duty of Care: (binary) There must exist a legally recognized duty to avoid harm to π. This both expands and limits negligence. ( ~duty of care -->~negligence). The existence of a duty is typically a judicial decision, with limited legislation. 2. Breach of Standard of Care: (Threshold) Δ conduct must fall below standard of care. 3. Causation: Δ's action must have caused the damages. 4. Remoteness: The damages cannot be too far removed from the action of the Δ. Another way to look at it: Core Elements: 1. Negligent Act (threshold) 2. Causation 3. Damage (above diminimus) Control Devices: 1. Duty of care (binary) 2. Remoteness of damage Defences: 1. Contributory Negligence (partial) 2. Voluntary assumption of risk (complete) 3. Illegality (complete) 4. Inevitable accident (complete) BG Checo International Ltd. v. British Columbian Hydro and Power Authority (SCC 1993) Negligence has roots in common callings. Mitchell v. Allestry (1676) the earliest example of a modern negligence case. Essentially involved a man trying to break his horses in on a public square. Modern Negligence Action: Negligence does not make any reference to state of mind. It is simply a cause of action that refers to conduct that falls below a usual standard. Negligence may be either an act or an omission; but in either case, Injury must result from this exposure, rather than simply exposure to risk. The 'reasonable person' is the standard against which the Δ's actions are held. Negligence seeks to find a balance between utility and associated risk of an action. The courts sometimes bounce back and forth between deterrence and compensation. 2.2 Duty of Care 2.2.1 Origins of Duty of Care Negligence: Standard of Care Palsgraf v. The Long Island Railroad Co. (NY CA 1928) Facts: Π was at a railway station where a passenger being helped onto a moving train dropped a package of fireworks which exploded and dislodged a scale which hit the π. Issue: Did the Δ owe a duty of care to the π? Held: Δ did not owe a duty of care to the π, even though the jury thought he did. Ratio: (Cardozo) There must be a specific duty owed to an injured person in order to assert negligence. Dissent: (Andrews) Wrong is established through exposing others to risk; deciding factor is whether the wrongdoer should be held laible. Dooghue v. Stevenson (House of Lords 1932) Issue: Held: Facts: Ratio: Did the Δ owe a duty of care to the π? A duty of care was owed. Decomposed snail in an opaque container of ginger beer. Persons have a general duty based on reasonable foreseeability. Neighbor principle: Duty of care arises from some relation or proximity between the parties(could be a class of people rather than a specific individual) N.B.: Courts retreated quickly from this position, and it redeveloped slowly. Home Office (defendant) v. Dorset Yacht Company (plaintiff) (House of Lords 1970) Issues: Facts: Held: Ratio: Did the prison guards have a duty of care to the yacht owners? Crown Immunity young men escape juvenile detention and damage some yachts. There is no policy reason against holding the prison guards liable, therefore they are liable. The neighbor principle is in full force except when there is a good policy reason not to apply it. Kamloops (City) v. Nielson (SCC 1984) Anns/Kamloops Test 1. No more than reasonable foreseeability of damage to the π. 2. Consideration off the societal costs/benefits of recognizing a duty of care. (i.e. a prima facie duty could be negated by policy, or another duty could be restricted, etc.) 2.2.2 The Current Approach to Duty Cooper v. Hobart (SCC 2001) Anns/Cooper Test Negligence: Standard of Care 1. (a)Was the harm that actually occurred a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the Δ’s act? (b)Is there a proximate relationship between the parties? Notwithstanding, are there good reasons that liability should not be recognized here? Note that physical, social, circumstantial, causal closeness can be considered, as well as closeness created by representation, assumption of responsibility, reliance, reasonable expectations (Osborne). In general, how do we differentiate the relationship to the π from the relationship to the world? (If the duty is novel) 2. Are there other policy factors that should negate the duty? 2.2.3 Examples of Proximity Proximity: Nearness in space, time or relationship. Foreseeability: Being aware beforehand or predicting. Note: Misfeasance: dangerous conduct; nonfeasance: failure to negate independently created dangers. Jordan House Ltd. v. Menow (SCC 1973) Facts: Ratio: Intoxicated driver failed to heed warning of another motorist. Hotel was aware of intoxication, but continued to serve (in violation of liquor laws). An alcohol-serving establishment owes a duty of care to patrons who become intoxicated and cannot look after themselves. Odhavji Estate v. Woodhouse (SCC 2003) Issue: Did the Police, Board, and Province breach a duty to take reasonable care to ensure that officers complies with an investigation? Facts: Held: Reasoning: Anns test: 1) Police chief can reasonably foresee that failure of his officers to comply with an investigation could harm the π. 2) There is a relatively direct causal link between alleged misconduct and the harm complained about. 3) There is already statutory obligation on the part of the chief to comply, thus no policy factors negate it. Ratio: Notes: Crocker v. Sundance Northwest Resorts (SCC 1988) Issue: Did the Δ have a positive duty to prevent an intoxicated person from participating in a dangerous event? Facts: Drunken π was allowed to compete in a dangerous tubing activity, resulting in quadriplegia. Held: 75%/25% split because of contributory negligence. Reasoning: 1. Was a duty of care owed? Negligence: Standard of Care a. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Yes. Commercial nature of competition, recognition of incapacity, with the foreseeability of danger to π. What was the standard of care? Was it met a. Δ had many opportunities to prevent the π from competing, none of which were a serious burden on the Δ, but none were taken. Standard was not met. Did failure to meet the standard of care cause the injury? a. Yes. An intoxicated person was clearly at greater risk. Was the risk voluntarily assumed by the π? a. No. Only applies where both physical and legal risks are assumed. Did the waiver create a contractual defence? a. Π did not realize he was signing a waiver—he thought it was an entry form. Was the π contributorily negligent? a. Yes. Ratio: Notes: Stewart v. Pettie (SCC 1995) Issue: Facts: Held: Is there a duty owed between an alcohol-serving establishment and a third party? Though a duty is owed, it is negated in this instance because: a. Drunk man was in care of 2 sober women (risk was therefore not foreseeable) b. Causation not proven. Ratio: 4. A duty is owed as a natural extension of the duty to one who is drinking, since harm of another is reasonably foreseeable. Notes: Childs v. Desormeaux (SCC 2006) Issue: Facts: Held: Does a social host owe a duty of care to someone injured by a guest who has consumed alcohol? Reasoning: 1. Is the duty novel? a. Yes. 2. Anns Test: a. Sufficient proximity—what links the hosts to 3rd party drivers? i. Foreseeable? No; if hosts did/ought not know Δ was impaired, no foreseeability. ii. Failure to act: 3 Categories for Positive duty: 1. Δ intentionally attracts π to inherent/obviously risky endeavour Δ creates/controls. 2. Paternalistic relationship of Supervision/control. 3. Public function or Commercial Enterprise with implied responsibilities to public at large. This case does not fall into these categories, nor is there justification for a positive duty otherwise. No need to move on to second stage of Anns test. Negligence: Standard of Care Ratio: “Hosting a party at which alcohol is served does not, without more, establish the degree of proximity required to give rise to a duty of care on the hosts to third-party highway users who may be injured by an intoxicated guest.” Notes: 2.2.4 The Duty to Warn Hollis v. Dow Corning Corporation (SCC 1995) Issue: Can a medical manufacturer fulfil its duty to warn by informing physicians of dangers associated with certain products? Facts: Reasoning: Ratio: Learned intermediary rule allows medical manufacturers to warn physicians where they will probably not be able to contact the consumer directly. The duty to warn in this case is continuing, and must be complete to be a discharge of the duty. Notes: 2.2.5 Medical Malpractice Reibl v. Hughes (SCC 1980) Issue: Facts: Ratio: What does a surgeon have to disclose to a patient in elective surgery? Pf was left half paralyzed from a stroke that came during or after an elective arterial surgery For informed consent, surgeon has to answer any specific questions asked about risks, plus disclose the nature of the material and special risks. (This includes risks with low probability but severe results like death or paralysis). Videto et al. v. Kennedy (Ont. C.A. 1981) Facts: Ratio: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Catholic woman undergoes laparotomy sterilization. Her bowel is perforated, leading to future surgeries and unsightly scars. She was not informed of this possibility. Professional standards are not conclusive regarding whether a risk is material and should be disclosed. Duty depends on what surgeon knew/should have known about the patient's concerns. 'Mere possibility' risks need not be disclosed. (Exception is if serious consequences follow, which makes these material risks.) Patient is entitled to an explanation of nature/gravity of operation. Dangers of anaesthetic, infection, etc. do not have to be disclosed (subject to above). Scope of duty must be decided on the facts of the case. Emotional condition may warrant generalization/withholding of specific information. Whether a risk is material and whether a duty is breaches are questions for the trier of facts. Brito (Guardian ad litem of) v. Woolley (BCCA 2003) Facts: Ratio: Mother sues Dr after cord prolapsed on second twin; thinks she should have been offered C-section. Risk should have been disclosed (low risk-bad consequence test) Negligence: Standard of Care Modified objective test—failure to disclose did not contribute to injury. Disclosure would not have changed decision for regular birth. Van Mol (Guardian ad Litem of) v. Ashmore (BCCA 1999) Facts: Ratio: 16 yr old girl left paraplegic after heart surgery; might have been avoided by newer technique not offered. Someone of “full age and capacity” is entitle to know about alternative methods with risks/advantages, and entitled to offer of a second opinion. 2.2.6 Rescuers and Good Samaritan Horsley (Next friend of) v. MacLaren (SCC 1971) Facts: Ratio: Boat operator follows improper procedure in rescue attempt; another passenger attempts rescue and dies. If rescuer is negligent in performing rescuer, he owes a duty of care (foreseeability) to another rescuer. Majority: Improper rescue attempt, but not negligent. Dissent: rescue was negligent; duty owed to pf. 2.3 Standard of Care 2.3.1 Unreasonable Risk 4 Factors Considered: 1. Probability of harm 2. Seriousness of potential injury 3. Cost of preventive measures 4. Utility of the risk-creating activity Bolton & Others v. Stone (England 1951) Facts: Ratio: Cricket ball hit out of field injures bystander; ball had been hit out of field ~6 times in 30 years. Test: not enough for something to be foreseeable, but rather whether risk is so small that a reasonable person would still refrain from taking further safety measures. Paris v. Stepney Borough Council (England 1951) Facts: Ratio: One-eyed man goes blind when eyes is struck by metal fragment at work. Amount of care that is reasonable depends on degree of the risk and the possible results that flow. 2.3.2 The Learned Hand Formula Formula: If Seriousness x Likelihood > cost of Avoidance, then risk is unreasonable. Rentway Canada Ltd. v. Laidlaw Trasnport Ltd. (Ont. C.A. 1989) Facts: Ratio: Two truck collide when one's tread separates and headlights blow. In product liability, the courts balance the risk and utility of the design against cost/availability of safer alternatives (essentially the learned hand formula.) Watt v. Hertfordshire (England 1954) Negligence: Causation Facts: Ratio: Car jack taken for emergency in vehicle not equipped for it; subsequently shifts and injures fireman. Risk must be balanced against measures needed to eliminate it; risk must also be balanced against end sought. Significant risks are reasonable when life/limb is to be saved. 2.3.3 Indices of Reasonableness Warren v. Camrose (City) (AB C.A. 1989) Facts: Ratio: Diver injured in municipal swimming pool. Uniform industry practice/expert consensus are not binding on courts, but very strong evidence. Pf cannot simply rely on possibility of other precautions when they are not commonly used and not unreasonable. Waldick v. Malcolm (SCC 1991) Facts: Ratio: Pf slipped on icy driveway visiting df. Custom is not decisive; unreasonable customs are no answer to the duty of care owed. 2.3.4 Departure from Custom Brown v. Rolls Royce (? 1960) Facts: Ratio: Pf developed dermatitis from consistent contact with oil. Claims failure to provide cream was negligent. Failure to follow usual practice may raise a prima facie case, but negligence is not inferred from it; negligence must still be proven. In this case, departure from custom is reasonable. 2.3.5 Statutory Standards Canada v. Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SCC 1983) Facts: Ratio: Infested grain necessitated fumigation; infestation was breach of statute. Breach of statute does not automatically imply breach of standard of care; this must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Gorris v. Scott (Exchequer 1874) Facts: Ratio: Sheep washed from ship; ship owner breached statutory duty relating to sanitation Statutory violation is not evidence of breach of care unless the statute aims to prevent the evil which actually occurred. Ryan v. Victoria (City) (SCC 1991) Facts: Ratio: Motorcyclist injured while crossing railway tracks; city argues that the tracks were in keeping with legislation. Negligence: Causation Compliance with a statute is not a sufficient defence against negligence; reasonable care must still be taken. 2.3.6. Professional Standards Brenner et. al. v. Gregory et. al.(O.R. 1973) Facts: Ratio: - Soliciter fails to order survey in property exchange, which ultimately reduces amount of land available to pf’s. Only negligence if soliciter failed to do what “an ordinarily competent solicitor” would do, unless specific instructions are given. ter Neuzen v. Korn (SCC 1995) Facts: Ratio: - Pf contracted HIV from artificial insemination procedure. It was not known generally at the time that HIV could be contracted in this way. Judge or jury cannot find negligence in regards to technical or complex procedures beyond their understanding, so long as there was conformity with professional standards. Exception is where standard practice fails to adopt obvious and reasonable precautions apparent to fact finder. 2.3.7 Determining Reasonable Behaviour Vaughan v. Menlove (England 1837) Facts: Ratio: - Hay caught fire and burned down adjacent cottages. Reasonable, ordinarily prudent person is the standard measure of care. 2.3.8 Special Standards: Children and the Mentally Ill Heisler et al. v. Moke et al. (Ont. H.C. 1971) Ratio: - Two questions for children: 1. Does this particular child have the faculty to be found negligent? 2. Did this child act like a reasonable child of her age? Pope v. RGC Management (AB QB 2002) Facts: Ratio: - 12 year old hits woman in the face with a golf ball. When a child is engaged in an ‘adult activity’, the reasonable person standard applies. Nespolon v. Alford et al. (Ont C.A. 1998) Facts: Ratio: - - Friends drop off drunk kid on side of the road where he wants to be dropped. He is later hit by a car and killed, causing the driver a psychological breakdown. Must ask not if overall activity is normally an adult one, but if specific activity giving rise to negligence allegations is an adult one: in this case, dropping off a friend is not an adult activity, and people in their position would not have reasonably foreseen the dnagre of nervous shock. Dissent: kids should have walked deceased to the door. Negligence: Causation Fiala v. Cechmanek (AB C.A. 2001) Facts: Ratio: - Undiagnosed bipolar man has episode, chokes a woman in her car, causing an accident. To escape liability, a sudden and without warning mental illness must: 1. Deprive peson of capacity to understand/appreciate duty of care, OR 2. Deprive person of ability to discharge duty of care (i.e., lose control of actions. 2.4 Causation 2.4.1 The ‘But For’ Test Athey v. Leonati (SCC 1996) Facts: Ratio: - Back injuries from a combination of car accident and stretching exercise. “but for” test is general test for causation; where it is unworkable, material contribution is used instead. Onus is on pf to show that df caused injury. Not necessary to establish that df negligence was sole cause of injury; no basis for reduced liability from preconditions. 2.4.2 The Difficulty of Proof Snell v. Farrell (SCC 1990) Facts: Ratio: - Woman goes blind in one eye after cataract surgery. Experts could not pin down exact cause, though a stroke had occurred in the eye, and there had been some complications in the cataract removal. Onus to show causation is on pf, and properly applied, the legal test is not too onerous. Causation “need not be determined by scientific precision” (para 29). Even if the pf’s evidence does not establish causation with certainty, failure to rebut by a df (especially one professionally able to do so like a doctor) will lead to an inference of causation. 2.4.3 Multiple Wrongdoers and Contribution Cook v. Lewis (SCC 1951) Facts: Ratio: - Pair are hunting; while both shoot, only one shot injures pf. Unable to prove which shot caused injury. Df’s not only caused injury, but made it impossible for the pf to determine which df caused injury (remedial right to establishing liability). Given this, the presumption of proving which did not cause the injury is on the pf’s. B.M. v. British Columbia (Attorney General) (BCCA 2004) Facts: Ratio: - - Pf brought againsit against an officer for failing to prevent an assault causing a murder and trauma to others involved. Donald J.A.: Haag test for inference of negligence: (i.e. can draw an inference of negligence when...) 1. Breach of duty occurred 2. Damage occurs in area of risk created by breach 3. Breach materially increased risk of damage of type that occurred. 4. Practically impossible to show if breach caused or did not cause loss Hall J.A. No indication that prior legal sanctions had much deterrence. Negligence: Remoteness - Smith J.A. Harm resulted from a discrete event; prior events were not causal. 2.4.4 Inadequate Supreme Court Analysis Resurfice Corp. v. Hanke (SCC 2007) When to use Material Contribution Facts: Ratio: - Man puts water hose in zamboni gas tank; gas fumes explode and he sues manufacturer. Requirement for material condition test instead of but for test: 1. Impossible for pf to prove injury with but for test. Impossibility must be because of something outside pf control (e.g. limits of science) 2. Pf’s injury must fall within area of risk created by breach of duty by df Walker Estate v. York Finch General Hospital (SCC 2001) Material Contribution Facts: Ratio: - Pf’s are people who have contracted HIV from Canadian Red Cross blood transfusions. Question at trial was whether proper screening would have prevented donation. SCC says that proper test in similar tainted blood cases is material contribution test, though this case will be decided on “but for” test, since trial judge asked the wrong question at trial. Material Contribution test: apply when “but for” test is unworkable. 2.4.5 Failure to Warn and Causation Martin v. Capital Health Authority (ABQB 2007) Medical Malpractice Facts: Ratio: 1. 2. Retired RCMP has a tumor to be removed; he is informed of some risk, and maybe of all, but not in understandable language. Stroke results, paralyzing him. Was there adequate disclosure? a. No: language was not clear enough to the layman to indicate the risk. If no, would a reasonable person if the pf’s situation have consented to surgery had he been informed of the risks? (causation) a. No: he had good reason to postpone. The fact that the surgery may have occurred later is irrelevant. Chester v. Afshar (UKHR 2004) Facts: Ratio: - Woman undergoes back surgery and is left crippled; she was not informed of that risk. As a matter of policy, it doesn’t matter whether a patient would have permanently declined the surgery or only postponed it. Causation is satisfied in either case. 2.4.6 Lost Chances and Medical Malpractice Laferrier v. Lawson (SCC 1991) Facts: - Doctor negligently forms to inform patient of malignant tumor which ultimately killed her; it highly uncertain if earlier treatment would have prevented death. Negligence: Remoteness Ratio: - - Loss of a chance of a favourable outcome is not compensable. (I.e. since negligence was established, but causation was difficult, pf sought compensation on the basis that she had lost the chance for a more favourable treatment. This approach is rejected.) See also Gregg v. Scott (UK 2005) 2.4.7 Causation and Industrial Torts: The English and US Experiments: Barker v. Corus UK Ltd, (UKHL 2006) Facts: Ratio: - Pf develops mesothelioma from exposure to asbestos. Self employed, and had failed to take adequate care of himself. Damage should be apportioned and is several (not joint). It’s fair to defendants but leaves the plaintiff uncompensated Legislature in the UK didn’t like the result and passed legislation saying that the plaintiff can recover everything except the portion for which they are personally responsible. Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories (US) Market Share Liability Facts: Ratio: - Drug causes cancer to daughters of takers. Many companies manufacture same drug with same formula, and cancer happens after many years, so it is difficult to establish causation. Court develops “market share liability”, where companies are responsible for the damages to the extent that they are likely to have provided the drug. The companies then have the onus to show that they did not supply the drug in a particular case. 2.5 Remoteness Overseas Tankship Ltd. v. Morts Dock & Engineering Company(The Wagon Mound No. 1)(UKPC 1961) Foreseeability test for remoteness Facts: Ratio: - Oil spillage and subsequent welding causes a fire that damages a ship and dockyard. The chain of events leading to the fire are seen as highly improbably. Liability depends upon reasonable foreseeability. Liability does not hold for highly improbable effects, even if they are directly or naturally caused by his actions. Similarly, even if an effect is not a direct result, if it is reasonably foreseeable, liability holds. Essentially overturns directness test from Polemis is favour of a foreseeability test Hughes v. Lord Advocate (HL 1963) Specific consequences that come about need not have been foreseeable Facts: Ratio: - Boy trips over lamp near open manhole left by workers on break; lamp explodes, boy falls in and is burned. Precise details leading up to or of an accident need not be foreseeable, so long as an injury of the same type is foreseeable. Assiniboine School Division No. 3 v. Hoffer (Man. C.A. 1971) General foreseeability of a sort of damage is sufficient for liability Negligence: Remoteness Facts: Ratio: - 14 yr old boy loses control of “auto toboggan” while starting it. It his a gas pipe near a school, causing gas to rise into the boiler room and cause an explosion and fire. It is enough to establish liability if one can generally foresee “the sort of thing that happened”. Specific extent and the way it occurs need not be foreseeable if the kind of damage is foreseeable. Lauritzen v. Barstead (Alta S.C. 1965) Facts: - Ratio: - Df. Is driving his drunk foreman. Foreman causes car to slip off the road. Df subsequently drives car farther into ditch. The two are essentially stuck in the car for several days and suffer frostbite. Pf’s wife leaves him as a result of being crippled. Recovery not dependent upon both foreseeability of particular harm and sequence of events giving rise to the harm. (Awarded damages for frostbite, lost wages etc. but not the leaving of his wife, as this was too remote.) 2.5.1 The Thin Skull Rule Bishop v. Art & Letters Club of Toronto et al. (Ont. H.C. 1978) Thin Skull Rule Facts: Ratio: - Older haemophiliac is severely injured when he pushes too hard on a door and falls down stairs. Thin Skull rule: once harm to pf is foreseeable, df is liable for all consequences of negligence, even if unexpectedly severe. Athey. v. Leonati (SCC 1996) Crumbling Skull Rule Ratio: - Limitation to thin skull (crumbling skull): df is liable for injuries caused, but not for effects of a preexisting condition that would have been experienced anyway. 2.5.2 Novus Actus Interveniens Bradford v. Kanellos (c.o.b. Astor Delicatessen & Steak House)(SCC 1974) Facts: - Ratio: - A fire breaks out on a restaurant grill because of negligence in cleaning. As a result, a CO2 fire extinguisher is activated, making a hissing sound. The sound causes a patron to yell that there is a gas leak, and everyone rushes from the restaurant. The pf is knocked off a stool and injured. Majority (per Martland) o Subsequent intervening event caused injuries, thus they were not foreseeable. Dissent (per Spence) o Actions of patron to yell “gas” was normal and foreseeable, thus df is liable. 2.5.3 Manufacturers, Distributors, Contractors and Remoteness Smith v. Inglis Lts. (? 1978) Facts: Ratio: A third prong cut off by delivery man allowed a defect in a refrigerator design to case the pf a severe electrical shock. Negligence: Remoteness - Even though the negligence of a third party contributed, the manufacturer should have seen this possibility, since the removal of the third prong was fairly standard practice. Therefore, the act was not an intervening negligent act. Good-Wear Treaders Ltd. v. D & B Holdings Ltd. et al. (N.S. C.A. 1979) Facts: - Ratio: - Tire company sells tires not suited for weight and use of truck, with a warning against the use of the tires but knowing full well they would be used in that way. Tires explode on a highway, causing an accident and killing three people. A company cannot escape liability to a 3rd party by warning a purchaser IF the company knows the purchaser will use the product against the warning. Stansbie v. Troman (? 1948) Facts: Ratio: - Contractor left alone in house leaves, shutting the door so that it does not lock. The house is burglarized. A duty must arise from relationship between parties. Where relationship is contractual, duty must arise within the scope of the contractual relation. Though the thief was the direct cause of the harm, the contractor failed to take reasonable care to prevent the very thing that happened, and is liable. 2.5.4 Multiple Medical Errors Issue: When a pf requires medical attention as a result of a df’s tortuous conduct, and the medical treatment (through error or negligent error) worsens the harm, who should be responsible for damages? Mercer v. Gray (Ont. C.A. 1941) Traditional Approach Ratio: - Complications/genuine medical errors: foreseeable as a result of the initial tort, thus the df is liable. Negligent medical errors: novus actus interveniens, therefore initial tortfeasor not liable for negligent treatment. Katzman v. Taeck (Ont. C.A. 1982) Modern Approach Ratio: - An intervening medical error might be seen as within foreseeable range of risk from initial tortfeasor. Doctor’s negligence may not be considered a novus actus interveniens. If it is negligent, doctor may be liable to pay df (not pf) for damages df pays to pf. 2.6 Defences to Negligence Actions 1. 2. 3. Contributory Negligence: Applies where pf contributes to her own injuries. Partial defence Result: apportionment of damages. Voluntary Assumption of Risk (volenti non fit injuria—“no injury is done to a person who consents”): Applies where someone voluntarily consents to both the physical and legal risks. i. Risk must be obvious and necessary to the activity. ii. Agreement can be express or implied. Full Defence. Illegality (ex turpi causes non oritur actio—”from a dishonorable cause an action does not arise”): Defence applies to: (Hall v. Herbert [SCC 1991]) Negligence: Remoteness i. Prevent profiting from illegal conduct ii. Damages sought to evade criminal penalty. Liability for Psychiatric Harm 3. Liability for Psychiatric Harm (Nervous Shock) 3.1 Historical Development of the Law Devji v. Burnaby (District) (BCCA 1999) Kamloops test for Psychiatric Harm (with clarifications) Facts: Ratio: - Girl killed in car accident from negligent maintenance of road after broken water main. Family is informed of her death, and subsequently visit the hospital to identify the body (which is not mangled or deranged), and claim psychiatric shock. Anns/Kamloops test is applicable. Temporal basis: it matters little if shock happens at the accident or at the hospital some time later. Psychiatric Harm: harm must be more than grief or surprise that naturally attend eath of a friend or relative. Mustapha v. Culligan of Canada Ltd. (SCC 2008) Leading case on Psychiatric Harm Facts: Ratio: - Man sees dead flies in sealed bottle of water; he subsequently develops a major depressive disorder. He was awarded $341,000 in damages at trial, but overturned at both appeal levels. Test for Liability: 1. Did the defendant owe the plaintiff a duty of care? Focuses on relationship between the two, tempered by foreseeability and policy. 2. Did the defendant’s behaviour breach the standard of care? 3. Did the plaintiff sustain damages? Psychological damages must be prolonged and more than the regular annoyances of life to be compensable. 4. Were the plaintiffs damages caused (at law) by the defendant’s breach? Remoteness concerns. Objective standard is applied; would a person of ordinary fortitude have suffered a damage? This foreseeability can change if the df knows the particular situation of the df. Liability for Pure Economic Loss 4. Liability for Pure Economic Loss 4.1 Recognized Categories - The general question is whether courts should recognize liability where no physical/psychiatric harm has occurred, only economic losses as the result of negligent behaviour. Courts recognize such losses in five cases: 1. Independent liability of statutory public authorities; 2. Negligent misrepresentation; 3. Negligent performance of a service; 4. Negligent supply of shoddy goods/structures; 5. Relational economic loss. 4.2 Negligent Misrepresentation Hedley Byrne & Co. Ltd. v. Heller & Partners Ltd. (HL 1964) It is possible to claim damages from negligent misrepresentation Facts: Ratio: - Advertising company who has booked advertising slots on behalf of a client seeks through its bank to find out if the client has good credit. Representation given back about credit was unfounded. Foreseeability is not a sufficient limit for economic losses. There are concerns about negligent words (they can be broadcast, sometimes professionals give opinions in social circumstances, etc.) A special relationship is needed—of trust or reliance. If reliance is reasonable in circumstances and one giving information knows it will be relied on, the necessary relationship exists. BG Checo International Ltd. v. British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (SCC 1993) Concurrent Liability in Contract and Tort Facts: Ratio: - - Powerline construction company makes a bid based on certain information, which turns out to be incorrect. They sue in tort and alternatively contract. Majority (Per McLachlin and La Forest) Right to sue in tort is not taken away by contract, though a contract may limit/negate tort liability. Concurent action in tort and contract can be pursued unless a valid provision indicates that the parties intended otherwise. Three cases: 1. Contract more stringent than tort. Probably wouldn’t sue in contract, though they can (i.e. for limitation dates, etc.) 2. Contract stipulates lesser duty than common law tort. Little reason to sue in tort, since tort liability is limited by contract. However, the provision must be clear and valid. 3. Contract and tort have coextensive duty. Either avenue is available as the plaintiff chooses. Dissent in part (Per Iacobucci) Contract does not preclude common law duty of care. If parties choose to stipulate duty expressly in the contract, consequences should be decided in contract. Liability for Pure Economic Loss Hercules Managements Ltd. v. Ernst & Young (SCC 1997) Refinement of Anns/Kamloops for Negligent Misrepresentation Facts: Ratio: - - Investors, relying on an apparently negligent audit statement, seek to sue auditors of a company that goes bankrupt. Underlying policy concern: indeterminate liability; no liability where it would become indeterminate. Anns/Kamloops test is proper for negligent misrepresentation, with one modification: o Under first branch, the reasonableness of reliance must be considered (since it is essentially assumed in other cases.) Duty of care arises under first stage of Anns/Kamloops where defendant ought to have reasonably foreseen reliance by the plaintiff on the representation, and that such reliance is reasonable. Avco Financial Services Realty Ltd. V. Norman (Ont. C.A. 2003) Negligent Misrepresentation does not preclude Contributory Negligence Facts: - Ratio: - - Husband and wife get second mortgage on home with insurance. Mortgage is renewed each year, along with insurance. Wife develops cancer, fails to qualify for insurance renewal, and subsequently dies. Husband cannot pay back mortgage. Mortgage rep. Made negligent misrepresentation about insurance. Negligent misrepresentation and contributory negligence can co-exist. For example, even if a negligent misrepresentation is made, but an extra step should reasonably be taken by other party and is not, this is contributorily negligent. There was not contributory negligence on the facts of this case. 4.3 Negligent Provision of a Service Haskett v. Equifax Canada Inc. et al. (Ont. C.A. 2003) Facts: Ratio: - Equifax continues to report bankruptcy even though it is no longer legal to do so. Similar to negligent representation, since the effect to the pf is based on his reliance. It should have been foreseeable that negligent misrepresentations could damage the pf. Not overrun by policy considerations of indeterminate liability. Reliance is close enough to be analogous. Wilhelm v. Hickson (? 2000) Lawyer liable for negligently drawing up a will Facts: Ratio: - - Beneficiaries sue for loss since lawyer negligently drafted will that otherwise would have benefited them. Problems with liability in this case: 1. Work done for testator, not beneficiary. 2. No reliance on lawyer by beneficiary. 3. Contractual relationship, which excludes third parties. 4. Even in concurrent liability, no duty owed to beneficiary. 5. Difficult of restraining a judgment in wills from application to inter vivos gifts. 6. Illogical to impose duty on lawyer where no duty exists on testator. Responses: 1. If no duty imposed, no one can make a claim. Liability for Pure Economic Loss 2. 3. 4. Need to assert the right that a person can direct where their property goes after their death. No injustice to the lawyer. Public reliance on lawyers for wills. B.D.C. Ltd. v. Hofstrand Farms Ltd (SCC 1986) Facts: Ratio: - Courier, not knowing what It is delivering, fails to deliver a Crown Grant document in time for registration to fulfill pf’s contract. As a result, pf’s contract comes to an end, and pf must pay back sums paid to it. Anns/Kamloops test is applicable. On the facts, fails proximity, since courier had no actual/constructive knowledge of potential effects on third parties. Further, there was no reliance by the plaintiff on the courier (the risk to the pf arose from its agreement with the Crown). Winnipeg Condominium Corporation No. 36 v. Bird Construction Co. (SCC 1995) Real and substantial danger test; liability of contractors and others in building construction Facts: Ratio: - - - Appeal concerns a motion to strike out the suit as disclosing no cause of action. Subcontractor does shoddy work that makes siding on condo dangerous. Non-original condo owners spend money to make the building safe, then sue contractor, subcontractor, and engineers for damages. There is a policy distinction between shoddy goods and dangerous ones. A subsequent owner can claim in damages the reasonable cost of making a building safe where contractors (or other parties) negligence causes the building to be in dangerous condition. (using real and substantial danger as the test.) This does not make contractors liable for an indefinite time, to an indefinite class, or for an indefinite amount. Time will be limited to life of building, (an practically much shorter); class is limited to future owners—totally foreseeable; cost is limited to amount necessary to make building safe. Not defeated by lack of contract, since this does not concern shoddy goods, but unsafe ones. Also not defeated by caveat emptor, since pf’s demonstrably not in the best position to discover defects (which was the underlying rationale for the policy). M. Hasegawa & Co. v. Pepsi Bottling Group (Canada), Co. (BCCA 2002) No pure economic loss claims in tort for non-dangerous shoddy products. Facts: Ratio: - K for bottled water; some bottled were found to contain mould, thus not sellable in Japan. Pf sues for damages for cost of the bottled water that it destroyed. No real and substantial risk to human health, thus does not fall under existing decisions for pure economic loss. Risks were allocated in contract; this suit is an after-the-fact attempt at insurance, thus no good for policy reasons. Note on Relational Economic Losses: - Apply where df negligently causes injury or property damage to 3rd party, where the pf suffers economic loss by virtue of relationship (usually contractual) it had with the 3rd party or damaged property This is the only category into which a joint venture is recognized. E.g. Norsk – barge damages bridge, causes economic damages to train company, as they had to be rerouted, since they normally used bridge route 4.5 New Categories Liability for Pure Economic Loss Design Services Ltd. v. Canada (SCC 2008) No duty of care between owner and subcontractors in tendering process Facts: Ratio: - Construction company loses out on bid to a non-compliant bidder. Not a case of relational economic loss, because no property was damaged. Not sufficiently proximate. Ultimately, liability would be indeterminate, since the chain from employers to employees, subcontractors, etc. goes on and on. No new duty of care recognized Tort Liability of Government 5. The Tort Liability of Government Kamloops (City) v. Nielson (SCC 1984) Introduction of operational/policy decision distinction Facts: Ratio: - Note: - Alderman builds a house, violating orders issued by the city. House is sold to someone who does not know about defects in foundation. If the city had made serious consideration of taking action and decided not to, it would be a policy decision. However, their complete failure to act and to consider the appropriate course of action is operational. After Nielson, Local Government Act now exempts municipalities from liability for unenforced bylaws, or for building permits it issues. Limitation period is 6 months, with notice of damage to the city within 2 months of damage occurring. Just v. British Columbia (SCC 1989) Differentiating policy and operation decisions of Government for Liability Facts: Ratio: - Man’s car struck by boulder that fell from slopes of highway, killing his daughter and injuring him. He sues the gov’t for negligent maintenance of the roadway. General principles for Crown Liability: o Does a duty of care exist? 1. Is there a sufficiently proximate relationship? Does statute exempt/obligate gov’t? Is a pure policy decision involved (not generally reviewable)? o Policy generally dictated at high levels, but may be made at lower levels of authority. o Rests on nature of decision, not decision maker. o Budgetary allotments are generally policy decisions. o Even policy decisions are reviewable if they are not a bona fide exercise of discretion. Is there an operational decision involved (reviewable)? o Is the system reasonable? o Has the system been reasonably carried out? o Are budgetary concerns influencing the operational decision reasonable? Cooper v. Hobart (SCC 2001) Statute determines scope of proximity for public authorities Facts: Ratio: - - Investors who advanced money to company suspended by registrar brings suit against registrar. At Stage 1 of the Anns test: o If the defendant is a public authority whose authority flows entirely from statute, then proximity is also delimited by statute. (e.g., does the statute serve to protect the pf or class of pf’s?) At stage 2 of the Anns test: o Is the decision a policy or operation one? Tort Liability of Government Note: - This will tend to make action against public authorities more difficult, since the proximate relationship must be suggested directly by the statute. Hill. V. Hamilton-Wentworht Regional Police Services Board (SCC 2007) Application of Cooper to Police Investigations Facts: Ratio: - - Allegedly Improper police investigation of a subject. Only applies to police investigation of specific subject, not any other relationship. Application of Cooper: o Prima facie duty—yes, since foreseeable, proximate (dealing with specific suspect, not a whole world of suspects) o Policy considerations: floodgates, chilling effect; both fail. In this case, pf loses on the question of whether the officer met the standard of a reasonable officer Immunity of Mothers 6. The Immunity of Mothers Dobson (Litigation Guardian of ) v. Dobson (SCC 1999) Mother does not owe duty of care to foetus Facts: - Woman being sued by her child who was injured in a car crash before he was born, allegedly due to the mother’s negligence. Ratio: Majority (Per Cory J.) A duty of care is owed by a mother to her foetus; however, policy negates this duty. The concern is that every aspect of a pregnant woman’s life could come under judicial scrutiny, with no rational limits. Further, it would be damaging to the relationship between mother and child to allow suits. As a second justification, Cory J. points to the difficulty of articulating the “reasonable pregnant woman” standard, and taking into account lifestyle choices of mothers. Ultimately, this is a place where intervention needs to come from the legislature, not from the courts. Dissent, per Major J. A born child suing for prenatal injuries does not assert foetal rights, and is consistent with the right of a born child to sue a third party for prenatal injury. In this case, finding liability does not restrict the choice of the mother, since she already was under legal obligations to drive with care. “Where a pregnant woman already owes a duty of care to a third party in respect of the same behaviour for which her born alive child seeks to find her liable, policy considerations pertinent to the pregnant woman’s freedom of action cannot operate so as to negative the child’s prima facie right to sue.” Concerns about familial unity would have to be equally applied, making it impossible for any child to sue a parent or vice versa. Note: Maternal Tort Liability Act (AB): in response to this case, the Alberta legislature has allowed that a mother can be liable to a child after birth for injuries sustained from the mothers use of an automobile, provided that she was insured. Liability is limited to what could be recovered under insurance. Preston v. Chow (2002 Man. C.A.) No Apportionment of blame to mother for prenatal negligence Facts: Ratio: Note: - Child suffers brain damage from exposure to genital herpes during birth; hospital is sued for negligence, and tries to have blame apportioned in part to the mother. Mother cannot be apportioned responsibility, as this is essentially the same as naming her a party to the suit. U.K. Legislatures have mandated that, where a parent shares responsibility for pre-natal injuries, liability of other party should be reduced by the amount of responsibility of the parent Negligence and Reproduction 7. Negligence and Reproduction Paxton v. Ramji (Ont. C.A. 2008) No duty of care owed by doctor to future child of patient Facts: Ratio: - - Child born deformed as a result of mother taking accutane. Husband had had vasectomy 4 1/2 years earlier. No duty of care owed by doctor to foetus because: o Although the harm is reasonably foreseeable, o Potential for conflicting interests could put doctor in impossible position, and o Relationship to foetus is indirect, since it goes through the mother. Even if a duty of care were recognized above, residual policy considerations would negate the duty. Ediger (Guardian ad litem of) v. Johnston (BCSC 2009) Paxton only applies to unconceived; physician owes duty of care to foetus Facts: Ratio: - Dr. attempts forceps procedure during birth; caesarean section undertaken, but not quickly enough to prevent serious brain damage. Long history of judicial recognition that a physician does owe a duty of care to a fetus as a consequence of his duty to the mother. Anything in Paxton concerning a living foetus is obiter. Negligence and Reproduction April 1 Notes Re-Cap: - Medical consent —children o Generally, parents provide consent, except in emergency situations. o No set age for consent, but generally under age 6, no consent needed. After age 6, required consent increases with age. o Between 6 and 14(ish), children might be able to refute consent to elective procedures. o ‘Mature minor’—one who can appreciate nature and consequence of treatment (i.e. risk/benefit of treatment or refusal) can generally consent. o Test for capacity varies from child to child and treatment to treatment; a subjective test. o S. 17 of the Infants Act; physician can only obtain consent from a child who understands the treatment. o Parens patriae—court can step in an act for the parents to make a decision for the child; cannot be used on a mature minor. o In B.C. s. 29 of Child Family and Community Service Act can allow courts to step in despite wishes of parents or mature minor under 19 , given that 2 medical opinions state that it is necessary for life or to prevent serious harm. Norberg v. Wynrib (SCC 1992) o o o La Forest: 2 Stage test for determining genuine consent in sexual battery 1. Proof of inequality between parties? 2. Proof of exploitation? Sopinka: judgment has little impact. McLachlin and L’Heureux-Dube: a stretch to argue that failure to treat caused harm from sexual contact. Dr. Liable on basis of fiduciary duty (independant of tort and contract) Fiduciary relationships are a special category of relationship where one party has power over the other, and acts in benefit for the other. (i.e. trustee holding property for the benefit of another). McLachlin extends the idea of a fiduciary duty, since this action could be best understood and compensated . 1st Criteria: ? 2nd criteria: exercise of power/discretion is unilateral in relation to interest of the beneficiary. 3rd criteria: beneficiary is particularly vulnerable to the exercise of the discretion. Because of this relationship, doctor owed a duty of good faith etc. and had violated this. Consent not relevant in a fiduciary duty, since it does not regard the actions of the beneficiary. 70k award, including a punitive fine. Though this judgment did not win out, it is still relevant to fiduciary obligations today. Non-Marine Underwriters v. Scalera (SCC 2000) See handout Issue: Does exclusion clause in insurance for “intentional or criminal act or failure to act” fit in this case? Decision: Unanimous: exclusion clause applies. Split: Which party has to prove consent in a trespass action for sexual battery (non-consensual sexual contact) Iacobucci (Minority): Negligence and Reproduction o - A new tort of sexual battery with a different onus of proof is needed. Since harm is the interference (i.e. actionable without proof of harm), tortfeasor must have only intended physical contact and then is responsible for the harm (According to Kodar). In most battery, consent is not an issue, and we don’t expect consent to harm. Where intent to harm is less obvious, consent is generally clear. Sexual activity is not inherently harmful (usually consensual), and only becomes harmful when non-consensual. Therefore, it is different from other forms of battery, and pf must prove non-consent to the sexual contact (instead of df proving consent) as a part of proving the element of offensive physical contact. McLachlin (majority): o No reason to abandon traditional onus of proof in battery; battery should be applied as is to unwanted sexual contact. o Historical context for onus of proof relating to bodily integrity etc. o Rights basis of battery (i.e. physical integrity, etc.) justify the onus of proof. Sexual contact is not the sort of contact we expect in daily life, and consent is not implied. To imply consent by shifting onus would deny protection of the law where it is most needed, and shift the focus to the pf’s actions, not the df’s, which runs the risk of victim-blaming. o Changes to this tort would also be inconsistent with changes in the criminal law (i.e. for honest but mistaken belief in consent requires that a df demonstrate he took reasonable steps to obtain consent.) Further, if the df believed he had consent, he is in the best position to demonstrate why he believed. Result: No change in onus of proof for sexual battery: df must prove consent to sexual contact (and all cases of battery). Constructive consent is a defence to sexual battery. (Note that mistake is traditionally not a defence). If the reasonable person would have believed that consent had been given, there will be no liability. Note that the criminal standard requiring the df to take reasonable steps is not imported into sexual battery. Limitation periods Limitation to bringing a tort action is 2 years from the date on which ability to raise the action arose (s. 3(2)(a) of Tort Limitation Act). Action must be commenced (not finished) 3 reasons: 1. Certainty: defendant should at some point know that they are not going to be held liable for past actions. 2. Evidence: memories fade, people die, etc. Businesses should not have to hold files forever, 3. Diligence: pf’s should be diligent in bringing actions. Limitation is an incentive to timely litigation. But what if damage occurs many years before you become aware of the harm? o Discovery date: liability period begins when damage is discovered (or should wrongfully have been discovered. o For child abuse, no limitation begins until you are 19. (M. v. M.—for cases of incest, limitation date does not start until the victim discovers the harm of the abuse)