What does it mean to “read” a text?

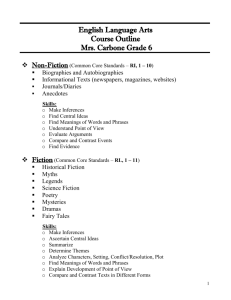

advertisement

8-28-12 (scheduled) 9-04-12 (actual) As we begin, please respond (in writing) to the following question: What does it mean to “read” a text? Consider: Did you “read” Woods Runner? How well did you read it? What were your purposes for reading? What did you “get” from reading? What strategies did you use for this novel that were different from reading, say, a textbook or newspaper? Major classroom question: How can you tell whether (or how well) someone has “read” a particular text, such as an assigned novel? Book Talks •No more than 2 per person per week •No more than 2 minutes long •Tell us the topic, but minimal plot summary •Goal is to generate interest (You’ll give us details in the review.) What does it mean to “read” a text? •Did you read Woods Runner? •How well did you read Woods Runner? •How can I tell whether or how well you read Woods Runner? •What makes for a good quiz? •How could/should I modify my plans if you have NOT read it (or have not read it well)? Last time, I asked, “Why do we teach literature to middle-school and high-school students?” Here’s what you said: to educate young minds about a variety of subjects to expose them to different cultures so they’ll know how to read to help them become better writers to teach them about themselves to entertain them because it’s in the curriculum to give them problemsolving skills because it’s just what teachers do to foster a love of reading to give them experiences beyond their own community to improve vocabulary to help them understand life lessons to teach them how to analyze and comprehend because we find truth through fiction Standard E4-1: The student will read and comprehend a variety of literary texts in print and nonprint formats. Students in English 4 read four major types of literary texts: fiction, literary nonfiction, poetry, and drama. In the category of fiction, they read the following specific types of texts: adventure stories, historical fiction, contemporary realistic fiction, myths, satires, parodies, allegories, and monologues. In the category of literary nonfiction, they read classical essays, memoirs, autobiographical and biographical sketches, and speeches. In the category of poetry, they read narrative poems, lyrical poems, humorous poems, free verse, odes, songs/ballads, and epics. The teacher should continue to address earlier indicators as they apply to more difficult texts. Indicators E4-1.1 Compare/contrast ideas within and across literary texts to make inferences. E4-1.2 Evaluate the impact of point of view on literary texts. E4-1.3 Evaluate devices of figurative language (including extended metaphor, oxymoron, pun, and paradox). E4-1.4 Evaluate the relationship among character, plot, conflict, and theme in a given literary text. E4-1.5 Analyze the effect of the author’s craft (including tone and the use of imagery, flashback, foreshadowing, symbolism, motif, irony, and allusion) on the meaning of literary texts. E4-1.6 Create responses to literary texts through a variety of methods, (for example, written works, oral and auditory presentations, discussions, media productions, and the visual and performing arts). E4-1.7 Evaluate an author’s use of genre to convey theme. E4-1.8 Read independently for extended periods of time for pleasure. Common Core State Standards for ELA, Reading Common Core State Standards for ELA, Reading Differentiated instruction (also known as differentiated learning or, in education, simply, differentiation) involves providing students with different avenues to acquiring content; to processing, constructing, or making sense of ideas; and to developing teaching materials so that all students within a classroom can learn effectively, regardless of differences in ability. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Differentiated_instruction) Differentiated instruction is based upon the belief that students learn best when they make connections between the curriculum and their diverse interests and experiences, and that the greatest learning occurs when students are pushed slightly beyond the point where they can work without assistance. This point differs for students who are working below grade level and for those who are gifted in a given area. Rather than simply "teaching to the middle" by providing a single avenue for learning for all students in a class, teachers using differentiated instruction match tasks, activities, and assessments with their students' interests, abilities, and learning preferences. (http://www.glencoe.com/sec/teachingtoday/subject/di_meeting.phtml) Which goals seem particularly well suited to canonical texts? Which goals seem particularly well suited to YA texts? Which goals seem appropriate for either kind of text? What, then, is an appropriate relationship between canonical texts and YA texts? Premise: Teachers can use YA Lit along with canonical literary texts and a variety of informational texts to teach ELA standards. So let’s start with a vocabulary for talking about literature… A shared vocabulary for talking about books Literary Terms CONFLICT •vs. God (or Society) •vs. Nature •vs. Another Person •vs. Self Climax Falling Action Rising Action Denouement Initiating Incident PLOT Possible points of view (of the narrator): 1. First person (“I”) 2. Second person (“You”) 3. Third person (“He,” “She”) -omniscient -limited omniscient -observer Some More Terms for Discussing Literature Allusion Assonance Character Climax Conflict Connotation Denotation Denouement Didacticism Dissonance Dynamic character Euphemism Exaggeration Falling action Figurative language Flashback Flat character Foreshadowing Hyperbole Imagery In media res Irony Motif Narrative hook Omniscient Oxymoron Paradox Personification Plot Point of view Protagonist Pun Rhythm Rising action Round character Setting Simile Static character Symbol Theme Tone Possible way to “evaluate” YA books… …Standard Literary Qualities Plot Characters Setting Theme Point of View Style …Use of Literary Elements metaphor simile flashback foreshadowing allusion humor imagery personification symbolism hyperbole effective beginnings main character as writer …Choice/Handling of Topic appropriateness of topic for audience accuracy/depth of content balance of various perspectives … Audience Appeal BREAK If you would like to “claim” two more books (from the library cart of from anywhere else), this would be a good time to do so. Remember, checking out a book from the class cart is NOT the same as “claiming” it for class; you need to sign the “claimed” list to “claim” a book. Learning History through Historical Fiction Using your book as necessary, list 10 facts about the Revolutionary War (or that time period in the US) that you didn’t know before reading the book. Exchange lists with someone; then, with your partner, find another set of partners (i.e., a group of 4) and exchange lists again, so that you read three other people’s lists. As a group, divide your information into categories: “weapons,” “fighting,” “prisoners,” etc. Be ready to share your categories with the rest of the class. US History is typically taught in 11th grade. How do you think 11th graders would respond to this book and this activity? In groups, brainstorm some other ways to use this book and others to teach about the Revolutionary War or the late 1700’s? (Consider: Chains / Forge series; Fever, 1793) Let’s start looking at some ways to USE these books (rather than KILL them)… What’s the point of view? What’s the verb tense, and what effect does it have? What does the last sentence of the first paragraph do to us? Considering that the speaker’s mother is “not so beatendown,” what can we infer about her life? What does the author tell us about the speaker? What do we know (or what can we infer) about the speaker? How do we know? Break (then move to 9/4/12 notes)