schaffer_poster - figuringoutmethods

advertisement

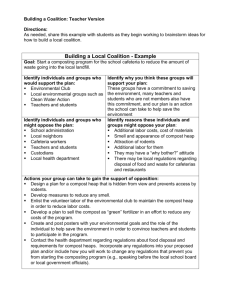

Global Waste Regimes and Local Waste Stewardship: Troy Compost and Cultural Innovation Guy Schaffer MS/Ph.D. Student, Science and Technology Studies Abstract The contemporary U.S. waste stream poses threats to environment, human health, and economy, but is managed to a point of near-invisibility by private haulers and municipal collection. However, a variety of actors and groups are working to make these problems visible, to pose alternatives to a throwaway culture and to “fix” the waste system. In this project, I work with one such group—an assortment of activists, researchers, organizers and farmers called Troy Compost—that opposes itself to a variety of structural problems in the U.S. waste system, as well as large-scale shifts toward forms of resource recovery that privilege industry, greenwash waste problems, and move resources out of communities. Instead, Troy Compost is working to develop a waste system that privileges the local and radically questions the division between waste and resource. In order to examine the cultural innovations developed in this context, I use participant observation at meetings and interviews with activists, I examine reports and public presentations, and work with the group to design and implement an alternative, decentralized resource recovery system for food and yard waste. How do these actors understand the relationships between waste and ownership, innovation, justice, environment and health? And how do these imaginaries of waste and society draw from and challenge status-quo formulations of waste problems, recovery solutions, and the responsibilities of individuals? Guy Schaffer is a secondyear student in the MS/PhD program in Science and Technology Studies, where he studies waste and waste systems using participatory methods and a pitchfork. Science and Technology Studies is an interdisciplinary field that studies the complexly interconnected and entangled social, technical, cultural and political economic systems that make up the late industrial world, with an eye not for the intractable complicatedness of the sociotechnical condition, but its navigability, its perverse sense--the problem is not to show that citizens, decision makers and scientists are lost in a sea of unnavigable knowledge, but to provide maps that situate us and show us ways forward. Studying Compost, Studying Garbage The bulk of my current work on this project is in the form of participant observation at Troy Compost meetings. This work has included helping to draft a report to city council along with the Citizen’s Working Group on Composting, organizing meetings, making connections with local waste managers and composters. In this process, I’m also working to elicit articulations of advocates’ assessments of waste problems, and the cultural innovation work that promises to construct new structures for dealing with waste. But the twin foci of this project—global waste regimes and emergent, local waste regimes— require multiple modes of inquiry. I am performing discourse analysis of municipal solid waste literatures with an interest in tracking down changing concepts of “waste producers” in changing policy environments, semistructured interviews with the managers of municipal composting programs, stewarding a neighborhood-scale compost pile that can collect foodscraps from 20 households, and working on a mapping project that can display not only the movement of wastes across states and between nations, but the concentration of resources in this and other neighborhood-scale composting projects. Proposed neighborhood-scale composting sites in Troy Building a compost bin at the Food Cycles lot in North Troy. Waste is a Global Problem The global waste system has produced a variety of interconnected problems that play out on the levels of climate, ecosystems, social justice and human health. There is too much trash, to be sure, but that’s just the tip of the garbage barge: wastes are harmful in their concentration in landfills and in their distribution across landscapes; they influence ecological and social systems in their movement across national borders and through oceans and groundwater; they impact the people who move garbage around, those who live near garbage, and those who have garbage pass through their lives. There is too much trash, but it is generated, moved around, processed, and disposed of in ways that are both social and technical, and have wide-reaching and deleterious effects. The patterns of production, circulation and destruction that define the life of global trash—and its tendency to “bite back”—can be viewed as a global waste regime (Gille, 2007). Trying to shift—or even trying to think—global waste regimes is never straightforward. It requires navigation between the scales of global waste and everyday disposal. Linking waste practices to waste problems becomes a site for knowledge production on the part of waste advocates. Waste is a Local Problem Troy Compost frames trash as not just a global problem but a local one, whose effects can be seen in local institutions and behavior and visible in local landscapes. Beyond the problems of landfills and leachates, or the sheer cost of waste disposal—$1.5 million per year for Troy in tipping fees alone—the problem of trash is a cultural problem, and the tackling it requires new kinds of value systems and new kinds of social structures. Throwing out trash is throwing out resources, as Troy’s compost advocates are quick to point out. And not just in the sense that organic waste can be composted or digested to produce methane. It’s throwing out opportunities for new systems of resource recovery that can bring communities together. More than that, callous disposal nurtures a throwaway attitude. “A city that throws away a banana peel is going to throw away people. It’s as simple as that,” explained Abby Lublin—prominent member of Troy Compost—at the group’s presentation to City Council. For these advocates, the problems of waste are at once environmental and social, local and global. Abby Lublin presents a plan for a municipal composting system to Troy’s City Council . EPA scientists board the Mobro 4000, the garbage barge that spent months at sea in 1987 looking for a place to unload its cargo. Cultural Innovations The emergent waste regime that members of Troy Compost are designing, discussing, and constructing involves a variety of departures from disposal-as-usual. It isn’t just green bins and foodscraps collection that these advocates are after; Troy compost envisions a city in which composting is exciting and “sexy,” in which communities can come together around a neighborhood compost bin and kids can learn about organic gardening by tending the compost heap. Troy compost envisions a fundamental shift in the attitude of Troy residents toward disposal, and the process of engineering this shift may be seen as a cultural innovation. What’s particularly exciting about this process of innovation is that it requires a constant negotiation between different imaginaries of waste problems, the nature of disposal (and the disposability of nature), and the roles of business, communities and government in managing the environment. In the construction of a neighborhood-scale composting system, these negotiations are being handled through adaptive management of multiple independent sites: a handful of compost bins are tended by one or two people; some bins are open for anybody to add to; others are restricted to a handful of neighbors; others pick up from households, all in an effort to work effectively within their communities. The people in charge of these sites then discuss what works and what doesn’t in order to aggregate local composting knowledge into effective, local, composting management. Research Significance This project builds on work in social movement studies, particularly that on science, technology and social movements, which seeks to characterize the role of social movements in challenging/creating scientific knowledge and new technologies. This is also situated within discard studies, a nascent interdisciplinary subfield that examines waste, its separation from/incorporation into societies, and the social, cultural, and technological structures that undergird and emerge from these complex relationships. Moreover, this work seeks to elucidate an emergent cultural innovation around waste: an ethics of wasting that might be understood as waste stewardship. This is a relationship toward waste that is characterized by care, rather than disgust, by responsibility rather than abjection. It is a tactical jettisoning of the concept of “away”; it recognizes that away does not exist and trash has an eminent and occasionally vindictive materiality, and that the status quo of disposal, destruction and marketization will only serve to worsen waste problems. Further Reading Brown, Phil & Edwin Mikkelsen. 1990. No Safe Place: Toxic Waste, Leukemia, and Community Action. Berkeley: University of California Press. Lublin, Abby, Anasha Cummings, Lucy Greetham, Mary Alice Pasanen, and Guy Schaffer. 2013. “Municipal Composting in Troy: Report of the Citizen’s Working Group on Composting.” Retrieved April 16, 2013 from troycompost.wikispaces.com. Corburn, Jason. 2005. Street Science: Community Knowledge and Environmental Health Justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Gille, Zsuzsa. 2007. From the Cult of Waste to the Trash Heap of History: The Politics of Waste in Socialist and Postsocialist Hungary. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press. McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York, NY: North Point Press, 2002. "2010 Solid Waste Capacity Chart," New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, accessed January 12, 2013,http://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/47984.html. Susan Strasser. 1999. Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash. New York: Metropolitan Books. Walsh, Edward, Rex Warland, and D. Clayton Smith. "Backyards, NIMBYs, and incinerator sitings: Implications for social movement theory." Social problems (1993): 25-38.