Intussusception - Oregon Health & Science University

advertisement

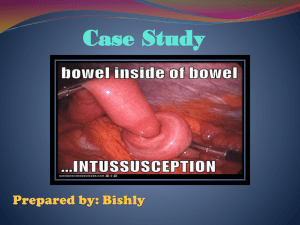

Jen Jen Chen MSIII Radiology, December 2006 Oregon Health and Science University What is IS? • 1 portion of the small bowel invaginating into the distal portion of small bowel, pulled in by peristalasis • Type of intussusception depends on segment of bowel that is involved – Starting at the ileocolic junction ileocolic intussusception Intussusceptum =proximal portion Intussuscipen =distal portion Epidemiology Second most common cause of acute abdominal pain in children following appendicitis Found between 3 months to 2 years of age, peaking at 5-7 months Variable incidence by geographical location ~ 0.9 - 4/1000 live births worldwide US: 0.5-2.3/1000 live births Declining rates recently, possibly from shift from inpt outpt 2:1 male to female Causes estimated 2.3 deaths/million and 18-56 hospitalizations /100,000 Theorized to have a seasonal pattern but only confirmed by two studies 3 types of IS: 1. Intraluminal = Mass pulled forward by peristalsis and brings continued bowel wall with it. 2. Intramural =Bowel wall abnormality prevents normal contraction, a.k.a. lead point 3. Extraluminal =Extraluminal abnormality prevents normal contraction, a.k.a. lead point Why does IS happen? Idiopathic 60% Most are ileocolic Lead point <10% •Most common is Meckel’s diverticulum •Other possibilities include : polyps, hemangiomas, lymphomas, cysts •American and European studies showing <10% of cases having a lead point More common post-abdominal surgery and in CF patients Hypotheses of etiologies: -Lymphoid tissue swelling -Dietary factors -Rotavirus and polio vaccine -Mesenteric LN swelling Just as a refresher… The Rotavirus Connection •Rhesus rotavirus tetravalent (RRV-TV) was introduced in 1998 as a 3 part vaccination (2, 4, 6 months) •Resulted in 15 cases of intussusception which occurred 3-14 days after the first injection •Withdrawn from market 9 months later •Total estimate of approximately 1 million doses to 0.5 million infants •Studies done after withdrawal showed risk of 1/10,000 – 1/32,000 •Possible causes -bolus of virus causing high viral titer -replication of wild-type rotaviruses •Pentavalent, bovine-human reassortant rotavirus vaccine and RIX4414 vaccine are on the horizon -safety trials underway Pathophysiology invagination of the bowel Obstruction resulting in compression of the vessels and venous congestion and bowel wall edema Infarction, perforation If left untreated, FATAL Classic Triad Colicky abdominal pain “Currant Jelly” bloody stools Abdominal Mass -sausage shaped -pulling knees up to abdomen •Multiple studies have shown that classic triad is only present in 20-50% •70% found to have 2 sx •9% found to have 1 sx Other common signs of presentation •Colicky pain – found to be best indicator 85% incidence 4-5 min of pain + pulling up knees to abdomen 10-20 min of rest •Lethargy •Dance’s sign = RUQ mass above RLQ space •Irritability •Vomiting •Diarrhea/Constipation •Up to 20% pain free on presentation Diagnosis The longer you take to diagnose, the higher the probability of surgery and mortality Diagnosis made by clinical presentation and imaging However, clinical suspicion can guide the modality of imaging… Abdominal X-Ray Conventionally, first-line modality for suspected intussusception Low sensitivity, high false negative rate Can be negative in early IS Uses: -Diagnosis of IS -Evaluating for risk of perforation before enema treatment -Diagnosis of other diseases (SBO, LBO, volvulus) •Findings: 1) Intracolonic mass 2) Target sign 3) Crescent sign 4) SBO 5) Presence/absence of gas in RLQ Where is the target sign? Created by gas trapped between two layers of intestinal wall Where is the crescent sign? Created by gas surrounding invagination Gas in RLQ? There is dilation of LUQ, but no presence of gas anywhere else in the bowel. Literature review •(Ratcliffe, et al) Four observers evaluated 1120 plain films for 4 IS signs (mass, target, crescent, SBO) Crescent sign most accurate, but least common (30%) Abdominal mass most unreliable, but most common (78%) Target sign in middle SBO not specific for IS •(Sargent, MA) Three observers evaluated 182 AXR (60 with IS, 122 without IS) to determine interobserver variability and validity of IS signs Agreement among all observers in only 7pts with IS Equivocal reading in >50% overall PPV of 32-42%, depending on position of AXR Abdominal mass and absence of RLQ gas has best PPV •(Hernandez, et al) Retrospective review of 80 AXR of known IS by 2 pediatric radiologists -Triad of mass, SBO, and absence of gas found in only 1% 24% found to be normal 29% diagnosed as IS -diagnostic findings are crescent and target sign Ultrasound •Used to diagnose IS and prevent unnecessary enemas High sensitivity and specificity No radiation exposure •Findings: -target sign (transverse) -pseudokidney or sandwich sign (longitudinal) Target Sign Central hyperechoic region (C) surrounded by hypoechoic and homogeneous edge (bowel wall) Sandwich sign Cylindrical hyperechoic center (C) that continues from intestinal lumen and is surrounded on both sides by hypoechoic mesentary (M) Literature •(Pracros, et al) Found 100% accuracy in diagnosing 145 cases of IS out of 426 pts with clinical suspicion -IS diagnosis must have 3 findings: target sign, sandwich sign (found longitudinally) and continuity between intestinal lumen and intussusceptum -Needs to be scanned in transverse and saggital section •(Verschelden, et al) US used to detect 34 cases IS out 83 pts with clinical suspicion -100% NPV -100% sensitivity, 88% specificity -False positives from 4 feces in colon and 1 perforated Meckel’s diverticulum •Both studies showed that target sign by itself is nonspecific – also occurs in Crohn’s, hematomas, and volvulus The Enema Conventionally considered the gold standard in diagnosis All 3 types are used, depending on institution BUT more invasive (and scary for kids!) -catheter placed into rectum -buttocks taped together -barium shot into bowels -fluoroscopy to confirm IS and reduce if possible And gives small dose of radiation Consider using smaller tube to introduce air to test for obstruction first, because would you really want this in your child??? 3 types of enemas: Pneumatic Pros – Clean, quick Cons – Less experience, more difficult to detect Is in pts with gas in SB proximal to IS Hydrostatic Pros - No staining of peritoneum Cons – Could cause rapid fluid shifts if not using isoosmolar concentrations Barium Pros – Familiar technique Cons – Perforation, higher chance of peritoneal contamination There are not yet any large, prospective studies comparing the success of pneumatic vs hydrostatic…stay tuned Pneumatic Enema: Before and After Barium Enema: From dusk till dawn Treatment 17% of IS spontaneously reduce 1st – NPO, IV fluids, NG tube 2nd – surgery consult Otherwise, tx by reduction enemas or surgery Reduction Enema •Successful when flow moves into ileum •Pt is under sedation •Disadvantages – missed lead points, higher recurrence rate, perforation, and radiation exposure •But benefits outweigh risks – less invasive than surgery, faster recovery Surgery •Indications – irreducible by enema, necrotic IS, age, long duration of sx, SBO, or clinical signs/sx of peritonitis or bowel infarction In a nutshell… Base your next move on CLINICAL SUSPICION… If low suspicion AXR -if negative, unlikely to be IS If medium suspicion AXR US -if US negative, unlikely to be IS If high suspicion, you can skip AXR and proceed directly to US Got skills? You are now the radiologist on call— Pt is 8 yo girl in ED with low-grade fever and colicky R abdominal pain. ED physician wants a barium enema. You think… WWADFBVD?? (What would a doctor from Burlington, Vermont do???) Answer: DON’T DO THE ENEMA!! It may be 2/3 of the classical triad, but THINK! Pt is too old to have an IS. Cases may happen, but it is not necessary to proceed directly to an enema. What if it was your kid? Choose an AXR to evaluate… What do you see? Look closer! Appendicolith!! The next night… ED calls for a 5 month old male with colicky abdominal pain and a RUQ longitudinal mass… See anything? Crescent sign! THE END!!! References Agostino JD. “Common abdominal emergencies in children” Emer Med Clinics of N Amer (2002) 20(1): 139-151. Bruce J, Soo YH, Cooney DR, et al. “Intussusception: evolution of current management” Journ Pediatr Gastroen and Nutr (1987) 6:663-674. Byrne AT, Goeghegan T, Govender P, Lyburn ID, Colhoun E, Torreggiani WC. “The imaging of intussusception” Clin Rad (2005) 60: 39-46. Daneman A, Alton DJ. “Intussusception: issues and controversies related to diagnosis and reduction” Pediatr Gastrointes Radiol (1996) 34(4): 743-756. Daneman A, Navarro O. “Intussusception, Part 1: A review of diagnostic approaches” Pediatr Radiol (2003) 33: 79-85. Daneman A, Navarro O. “Intussusception, Part 2: An update on the evolution of management” Pediatr Radiol (2004) 34: 97108. Daneman A, Navarro O. “Intussusception, Part 3: Diagnosis and management of those with an identifiable or predisposing cause and those that reduce spontaneously” Pediatr Radiol (2004) 34: 305-312. Fischer TK, Bihrmann K, et al. “Intussusception in early childhood: a cohort study of 1.7 million children” Pediatr (2004) 114(3): 782-785. Hernandez JA, Swischuk LE, Angel CA. “Validity of plain films in intussusception” Emer Rad (2004) 10: 323-326. Huppertz HI, Soriano-Gabarro M, et al. “Intussusception among young children in Europe” Pediatr Inf Dis Journal (2006) 25(1): S22-S29. Meyer JS. “The current radiologic management of intussusception: a survey and review” Pediatr Radiol (1992) 22:323-325. References cont. Pracros JP, Tran-Minh VA, Morin De Finfe CH, Deffrenne-Pracros P, Louis D, Basset T. “Acute intestinal intussusception in children: contribution of ultrasonography (145 cases)” Ann Radiol (1987) 30(7): 525-530. Ratcliffe JF, Fong S, Cheong L, Connell PO. “The plain abdominal film in intussusception: the accuracy and incidence of radiographic signs” Pediatr Radiol (1992) 22: 110-111. Sargent MA, Babyn P, Alton DJ. “Plain abdominal radiography in suspected intussusception: a reassesment” Pediatr Radiol (1994) 24:17-20. Verschelden P, Filiatrault D, et al. “Intussusception in children: reliability of US in diagnosis – prospective study” Radiol (1992) 184: 741-744.