Are children's rights still human?

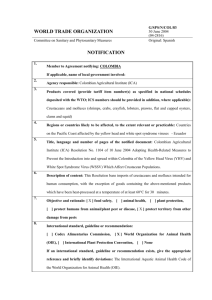

advertisement

Regaining lost ground: tackling the practices that put children's rights at risk in intercountry adoption Nigel Cantwell Conference on ‘Redefining Adoption in a New Era’ University College Cork, Ireland – 5 September 2014 The ‘lost ground’… Concern about problems in ICA usually focuses on tackling more effectively activities that violate human rights and are already prohibited – trafficking, fraud, etc. However, there are many practices that are tolerated or have even been consecrated in ICA systems, legislation and agreements that similarly jeopardise respect for the rights of the child. In addition, while the ‘best interests of the child’ are to be nothing less than ‘the paramount consideration’ in adoption decisions, there is still a disturbing lack of consensus on how they are to be determined. This is the ‘lost ground’ that must be regained in ‘a new era’. Money matters Cf. Hague PB Note on the Financial Aspects of ICA (2014) Development Aid Contributions/donations What is the child rights-based logic of requiring, and agreeing to provide, development aid in exchange for the ‘right’ to adopt children abroad? Implications of PAPs being required to fund this aid (e.g. prohibited in Sweden, but mandatory in Ireland for VN) Inter alia largely contribute to perpetuating residential care in the country of origin: the paradox of ‘orphanages’ funded from abroad Administrative fees Arbitrary requirements set by countries of origin (and accepted by receiving countries) Pressure Pressure on potential countries of origin to open up ICA programmes Pressure not to suspend or close ICA programmes The very sticky ‘country of origin’ label The role of Central Authorities Non-Hague countries From flood to drought (DRC…) Oversight and cooperation, not promotion Post-disaster situations: the litmus test of respect for standards Haiti: ‘expedited’ adoptions or unwarranted evacuations? The ‘agency system’ Involvement of private agencies is a legacy from the very start of ICA when it was unregulated (idem ‘independent adoptions’) By the time regulation began, their role had become almost unquestioned, and was solidly formalised in HC 1993 How well-equipped and qualified are agencies to mediate, in particular, the ICAs of ‘the new era’? What are the possible implications for children’s rights when agencies are wholly or mainly financed by PAPs? However ‘ethical’ they are – and paradoxically sometimes precisely because of their ethical approach – many agencies are fighting for survival in ‘the new era’: a potentially very dangerous situation for children’s rights… Examining ‘adoptability’ [1] Material poverty? Irish Law Reform Commission doc (2008): ICA is more accessible than domestic adoption ‘because a child is generally available for adoption in an intercountry context, such is the extent of deprivation in many countries…’ Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children (2009), § 15: ‘Financial and material poverty, or conditions directly and uniquely imputable to such poverty, should never be the only justification for […] receiving a child into alternative care […] but should be seen as a signal for the need to provide appropriate support to the family.’ Surely all the more relevant for definitive decisions on ICA… Examining ‘adoptability’ [2] ‘Relinquishment’ or ‘abandonment’? The influence of national law Guatemala: the vast majority of children in ICA were ‘relinquished’ because law made abandonment difficult to prove + court procedure required (-> moratorium) Nepal: most children in ICA were ‘abandoned’ because law made it difficult to disprove… (-> US: 73 ICAs in 2004, just 3 in 2012) The ‘best interests’ trap [1] “We will work to achieve excellence in adoption and adoption related services, with the best interests of children as our primary consideration.” “[W]e will remember the lessons of family separation. Our focus will be on protecting the fundamental rights of children…” The ‘best interests’ trap [2] International human rights treaties mention consideration of “interests” or “best interests” solely in relation to children No mention of best interests (of anybody!) in international humanitarian or refugee law Only as regards children in private international law: HC 1965 Art 6: the authorities ‘shall not grant an adoption unless it is in the interest of the child’; HC 1993 Art 4: an intercountry adoption shall only take place if the competent authorities of the State of origin have determined that it is in the best interests of the child The ‘best interests’ trap [3] 1959 Declaration (+ first Polish CRC proposal 1978) Principle 2: The child shall enjoy special protection, and shall be given opportunities and facilities […] to enable him to develop physically, mentally, morally, spiritually and socially in a healthy and normal manner […]. In the enactment of laws for this purpose, the best interests of the child shall be the paramount consideration. 1989 CRC (with no prior debate on ramifications) Art 3: In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration. The ‘best interests’ trap [4] ‘Best interests’ concept deliberately left vague/flexible… … yet elevated to ‘the paramount consideration’ for adoption… … and is designated a General Principle of the CRC underlying interpretation of the whole treaty, while being seen as superfluous or even counter-productive for achieving the human rights of others. Symptomatically, CRC Committee General Comment #14 took 23 years to appear, yet resolves little for ICA decisions… ‘Best interests’ can be useful as foreseen grounds for derogation from a specific right, or in a choice between two or more rightscompliant solutions, but agreed assessment and determination responsibilities, procedures and criteria are then needed The ‘best interests’ trap [5] We ‘invite’ countries to carry out ICAs, then complain about their inadequate resources or commitment for best interests determination – or in some cases we contest the outcomes of that process, particularly at policy level Receiving countries’ actions often betray very divergent interpretations of ‘best interests’ as ‘the paramount consideration’ – e.g. selective moratoria and closures in Cambodia, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Haiti, Viet Nam… This also sends confusing and erroneous messages to countries of origin as to what ICA is about Without consensus, on what basis can respect or non-respect for ‘best interests’ be argued? By way of conclusion… Many challenges for law and practice in the new era: difficult for one country to act alone, but… Opportunities to improve policy: Refuse country of origin demands for development aid or contributions from any source involved in ICA Encourage applications for bilateral aid + positive responses Refuse to countenance ICAs from non-Hague States Examine reasons for declarations of ‘adoptability’ Opportunities to improve practice: Ensure accredited agencies are viable without PAP fees Refrain from exerting pressure in all forms Initiate moves to consensus on best interests determination