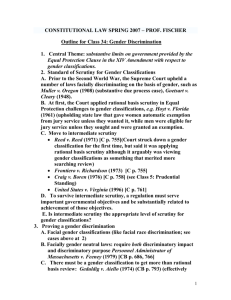

Equal Protection

advertisement

Philosophical Considerations Two forms of injustice: Treating people “similarly situated,” i.e., equals, differently in terms of liabilities imposed or benefits granted or withheld Treating people “unsimilarly situated,” i.e., unequals, the same in terms of liabilities imposed or benefits granted or withheld Nearly all laws are based on “classifications” What characteristics are significant enough to justify a “classification”? Under what circumstances is differential treatment based on that classification justified? “Suspect” classifications trigger “strict scrutiny” level of review 1. STRICT SCRUTINY -- The government must show that the challenged classification serves a compelling state interest and that the classification is necessary to serve that interest. Application of strict scrutiny analysis A. When the law creates a “Suspect Classification”: 1. Race 2. National Origin 3. Religion (either under Equal Protection or Establishment Clause analysis) 4. Alienage (unless the classification falls within a recognized "political community" exception, e.g., voting rights, in which case only rational basis scrutiny will be applied). B. When Classifications Burden Fundamental Rights 1. Denial or Dilution of the Vote 2. Interstate Migration 3. Access to the Courts 4. Other Rights Recognized as Fundamental Nearly all laws are based on “classifications” “Suspect” classifications trigger “strict scrutiny” level of review: race, ethnicity, and religion are the primary examples “Nearly suspect” classifications trigger “intermediate” level of review: The government must show that the challenged classification serves an important state interest and that the classification is at least substantially related to serving that interest.): Quasi-Suspect 1. Gender 2. Illegitimacy Classifications: Nearly all laws are based on “classifications” “Suspect” classifications trigger “strict scrutiny” level of review: race, ethnicity, and religion are the primary examples “Nearly suspect” classifications trigger “intermediate” level of review: gender, alienage, and legitimacy are primary examples “Non-suspect” classifications trigger “rational basis” level of review: The government need only show that the challenged classification is rationally related to serving a legitimate state interest.) Minimum scrutiny applies to all classifications other than those listed above, although some Supreme Court cases suggest a slightly closer scrutiny ("a second-order rational basis test") involving some weighing of the state's interest may be applied in cases, for example, involving classifications that disadvantage mentally retarded people, homosexuals, or innocent children of illegal aliens. Common examples of non-suspect classifications - age, income level, disabilities Equal Protection Clause of 14th Am. Originally intended only to protect interests of blacks vis a vis whites “State action requirement” Civil Rights Cases of 1883 overturned Civil Rights Act of 1875 which had been passed under §5 of 14th Am. but sought to prohibit “private actors” Civil Rights Act of 1964, passed under Commerce Clause of Art. I, §8, accomplished the same purpose of forbidding discrimination of private actors involved in interstate commerce “State-private” distinction survives, but Court has enlarged the concept of “state action” Extent of gov’t entanglement with private parties private actors practicing racial discrimination can lose gov’t. benefits such as grants, contracts, leases, tax exemptions or deductions, tax-exempt status judicial non-enforcement of private contracts [Shelley v Kramer(1948) involving restrictive covenants] access to political process [Reitman v Mulkey(1967) invalidated CA’s Prop. 14 repealing anti-discrimination law in real estate transactions – state cannot legislatively embrace a regime of discrimination, even for individuals] Limits on this doctrine – when state requires the entanglement by licensing requirements [Moose Lodge v Irvis (1972), issuance of liquor license] When the nature of the activity is “statelike” (state had delegated its function to a private party or the private function is so “affected with the public interest”) White primaries in South [Smith v Allwright, (1944) ruled on 15th Am., but with language of state-private analysis] From Desegregation to Integration District courts given wide powers to remedy the effects of de jure segregation (Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed.,1971) Principle extended to de facto segregation if Any evidence of “state involvement” to maintain segregated schools, even in the absence of a law requiring a dual system Drawing of school attendance boundary lines or pupil assignment schemes Decisions about the placement of schools (Keyes v Denver School District, 1973) From Desegregation to Integration But courts cannot fashion a remedy broader than the scope of violations Especially relevant in inter-district school busing plans (Milliken v Bradley, 1974) Even remedies for previous segregation will be subject to stricter scrutiny (MO v Jenkins, 1995) How far can the state go in correcting the historic consequences of discrimination? Controversies over “affirmative action” and “reverse discrimination” Philosophical issue: group-based vs individualistic conceptions of rights, e.g., am I entitled to special treatment because my ancestors were victims of discrimination even though I have not been personally? Is there a sufficient “residual effect” of discrimination against previous generations to deprive me of “equality” today? Racial classifications are suspect even when used to benefit the “classified” group because such schemes inherently burden members of the nonprivileged groups Court has waffled on the extent of permissible race & gender-based legislative benefits Generally upheld the abstract principle of “affirmative action,” i.e., race, gender can be “taken into consideration” as a legitimate means of pursuing the state’s interest in promoting diversity to remedy the effect of previous discrimination (Bakke principle) EXCEPT in the 5th Circuit as a result of Hopwood v TX, 1995 and in CA as a result of Prop. 209 Court has sidestepped these challenges to the fundamental premise of affirmative action by denying cert. on appeals from adverse lower court rulings Court has waffled on the extent of permissible race & gender-based legislative benefits Generally disallowed rigid quotas and percentages in “set asides” – major exceptions have been to remedy long-standing, entrenched, de jure segregation Seats in graduate/medical/law programs (U.C. v Bakke, 1978) Minority contracts and hiring (Richmond v J.A. Croson Co., 1989 overturned Fullilove v Krutznick, 1980) Previous distinction between federallymandated and state-mandated set-asides, established in Metro Broadcasting v FCC, 1990 overturned in Adarand v Peña, 1995 Strict scrutiny standard applied to all racebased classifications When are differential/discriminatory results of policy permissible? Job requirements/performance criteria may produce racially or gender skewed results/outcomes [“disparate results”] if Facially non-discriminatory Rationally related to the requirements of the job The Davis rule – Washington v Davis (1976)