Class Outline

advertisement

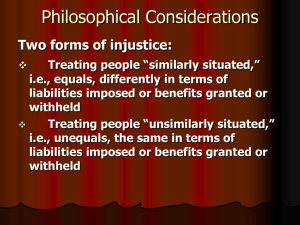

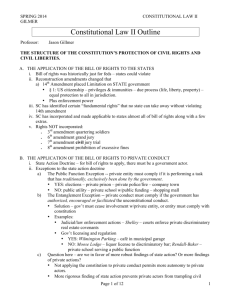

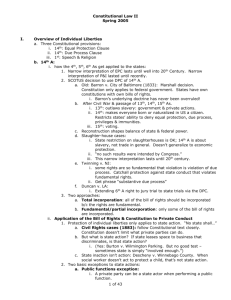

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW SPRING 2007 – PROF. FISCHER Outline for Class 34: Gender Discrimination 1. Central Theme: substantive limits on government provided by the Equal Protection Clause in the XIV Amendment with respect to gender classifications. 2. Standard of Scrutiny for Gender Classifications A. Prior to the Second World War, the Supreme Court upheld a number of laws facially discriminating on the basis of gender, such as Muller v. Oregon (1908) (substantive due process case), Goetsart v. Cleary (1948). B. At first, the Court applied rational basis scrutiny in Equal Protection challenges to gender classifications, e.g. Hoyt v. Florida (1961) (upholding state law that gave women automatic exemption from jury service unless they wanted it, while men were eligible for jury service unless they sought and were granted an exemption. C. Move to intermediate scrutiny Reed v. Reed (1971) [C p. 755](Court struck down a gender classification for the first time, but said it was applying rational basis scrutiny although it arguably was viewing gender classifications as something that merited more searching review) Frontiero v. Richardson (1973) [C p. 755] Craig v. Boren (1976) [C p. 758] (see Class 5: Prudential Standing) United States v. Virginia (1996) [C p. 761] D. To survive intermediate scrutiny, a regulation must serve important governmental objectives and be substantially related to achievement of those objectives. E. Is intermediate scrutiny the appropriate level of scrutiny for gender classifications? 3. Proving a gender discrimination A. Facial gender classifications (like facial race discrimination; see cases above at 2) B. Facially gender neutral laws: require both discriminatory impact and discriminatory purpose Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney (1979) [CB p. 686, 766] C. There must be a gender classification to get more than rational basis review: Geduldig v. Aiello (1974) (CB p. 793) (effectively 1 overruled by Pregnancy Discrimination Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000(e)(k). D. Gender Discrimination Benefiting Women i. Based on stereotypes Orr v. Orr (1979) [C p. 769] Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (1975) [C p. 770 Califano v. Goldfarb (1977) [C p. 770] Wengler v. Druggists Mutual Insurance Co. (1980) [C p. 771] Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan (1982) [C p. 771] Sex-specific Statutory Rape Laws: Michael M. v. Superior Court (1981) [C p. 774] Draft Registration: Rostker v. Goldberg (1981) [C p. 776] ii. Designed to remedy past discrimination: Califano v. Webster (1977) [C p. 780] iii. Gender Classifications Benefiting Women Because of Biological Differences Between Men and Women: Nguyen v v. INS (2001) [C p. 781] 4. ILLEGITIMACY CLASSIFICATIONS (DISCRIMINATION AGAINST NONMARITAL CHILDREN) A. What level of scrutiny is used? Clark v. Jeter (1988) [C p. 804] B. Laws that provide benefits to marital children but deny them to ALL nonmarital children are generally struck down: Levy v. Louisiana (1968) [c p. 805], Trimble v. Gordon (1977) [C p. 805] C. No bright-line test for laws that provide a benefit to some nonmarital children, but deny to others: Lalli v. Lalli (1978) [C p. 806], Labine v. Vincent (1971) [C p. 806], Mathews v. Lucas (1976) [C p. 806], Jiminez v. Weinberger (1974) [C p. 806] 2