Consumption - Nuffield College

advertisement

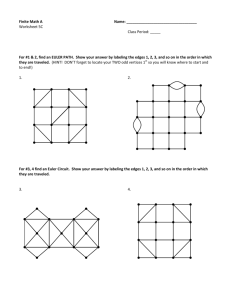

Consumption Anthony Murphy Nuffield College anthony.murphy@nuffield.ox.ac.uk Outline • Consumption – the biggest component of GDP/national expenditure; a good deal smoother than income. • The two period model. • Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis PIH infinitely lived representative agent etc. • Modligiani’s life cycle hypothesis LCH – finite life, saving for retirement, population dynamics. • Hall’s consumption function – uncertainty, rational expectations and the consumption Euler equation. • Euler equations versus (approx.) solved out consumption functions – pros and cons. • Example of solved out consumption function for US. Basic Two Period Model (1) Diagram: • Axes - c1’y1 on horizontal axis (the present) and c2,y2 on vertical axis (the future). • Intertemporal preferences: Regular shaped indifference curves (as opposed to linear or L shaped ones). • Less than perfect trade-off between c1 and c2 so want to smooth consumption over time. • Intertemporal budget line: c1+c2/(1+r) = y1 + y2/(1+r) (You can add an initial endowment a0(1+r) if you want to the RHS of the budget.) Fig. 6.02(a) Consumption tomorrow Indifference curves: Normal case 0 Consumption today Fig. 6.02(b) Consumption tomorrow Indifference curves: Zero substitution 0 Consumption today Fig. 6.02(c) Consumption tomorrow Indifference curves: Constant substitution 0 Consumption today Two Period Model (2) • Budget constraint is a straight line thru’ (y1,y2) point with slope equal to minus 1/(1+r). • No borrowing or lending restrictions. • Borrowing and lending rates are the same. • Intertemporal budget constraint got by combining period 1 and period 2 budget constraints: c1 + a1 = y 1 c2 = a1(1+r) + y2 Equilibrium in Two Period Model • Equilibrium where highest attainable indifference curve is tangential to the budget line. • You may be a borrower (c1 > y1) or lender (c1 < y1) in period 1. • First order condition (FOC): slope of indifference curve = slope of budget line ie. marginal rate of substitution (MRS) between c1 and c2 = 1/(1 + r). Fig. 6.03 Consumption tomorrow Optimal consumption: borrower D (i) Consumption today financed on credit M Y2 (ii) Consumption loan repayment (including interest) (ii) R C2 (i) 0 Y1 IC1 -(1+r) C1 B IC2 IC3 Consumption today Fig. 6.03 Consumption tomorrow Optimal consumption: lender D (i) Saving from this period’s income (ii) Additional consumption next period R C2 (ii) Y2 A (i) -(1+r) 0 C1 Y1 B IC1 IC2 IC3 Consumption today FOC and Euler Equation* • Suppose preferences are additive over time so U(c1,c2) = u(c1) + u(c2) where 0 < < 1 is a discount factor. • MRS = -dc2/dc1 holding U constant = u'(c1) / (u'(c2)), where u'(c1) is the marginal utility of c1 etc. • Thus FOC may be re-written as: u'(c1) = (1+r)u'(c2) FOC and Euler Equation* u'(c1) = (1+r)u'(c2) • This is just a non-stochastic Euler equation! • Note intuition – indifferent between shifting one unit of consumption between the present and the future. • Complete smoothing of consumption (c1 = c2) when = 1/ (1+r). CRRA Preferences* • CRRA preferences appealing – constant savings rate & fixed allocation of wealth across assets when interest rates constant. • u(c) = c1-γ/(1-γ) with γ positive; u'(c) = c-γ so Euler equation is: c1-γ = (1+r)c2-γ • Take natural logs and note that ln(1+r) is approx. equal to r so: lnc2 = (ln )/γ + r/γ CRRA Preferences (2)* • The elasticity of intertemporal substitution EIS is the coeff. on r in the Euler equation. • The EIS is 1/γ, the inverse of the constant coeff. of relative risk aversion. • The Euler equation implies that a higher interest rate increases savings (c1 falls and c2 rises). • However, need to examine this effect in more detail. (Why? Only looking at slope of budget line not position of line). Playing Around with the Basic Two Period Model • Rise in permanent income (both y1 and y2 rise) – outward parallel shift in budget line. c1 and c2 both rise. • Rise in current or future income – budget line shifts out parallel but not by as much as above. Ditto for c1 and c2. • Current consumption is higher if future income rises even if current income is unchanged! • A transitory rise in income may be represented by a small rise in y1 (and possibly a offsetting small fall in y2?). c1 and c2 only rise by a small amount. Real Interest Rate Effects (1) • Suppose r rises. • Budget line swivels around (y1,y2) and is steeper. • Need to look at substitution and wealth effects. • Substitution effect given by Euler equation. • Substitution effect on c1 is negative. Real Interest Rate Effects (2) • For borrower, wealth effect on c1 is also negative. • For lender, wealth effect on c1 is positive. • Overall, the effect of a rise in real interest rate on current consumption is not clear cut. • Empirical consensus is that interest rate effect is small and negative. • Size of effect depends on incidence of credit constraints and initial wealth, inter alia. Fig. 6.09 D A R R´ B´ B Consumption today (a) Student Crusoe (borrower) Consumption tomorrow Consumption tomorrow Effect of an increase in the interest rate: negative income effect for borrowers, positive for lenders D R´ R A B´ B Consumption today (b) Professional athlete (lender) Credit Constraints (1) • Assume that representative agent cannot borrow in period 1. • Budget line is now discontinuous at (y1,y2). • Budget line same as before in lending region i.e. to left of (y1,y2). • Budget line drops down to horizontal axis in borrowing region i.e. to right of (y1,y2). Credit Constraints (2) • Now a corner solution at (y1,y2) is a distinct possibility. • A rise in future income y2 has no effect on current consumption if credit constrained. • A permanent or transitory rise in current income has a large effect if credit constrained (marginal propensity to consume is one). • Interest rate effects smaller or zero if credit constrained. Fig. 6.11 Consumption tomorrow With a credit constraint, the choice set is reduced. C A R 0 B D Consumption today Permanent Income & Life Cycle Hypotheses (1) • Can generalize analysis from two periods to many or an infinite number of periods. • Standard model often called PIH–LCH model. • Original permanent income model of consumption uses a rational, infinitely lived, representative consumer. • Emphasis on different response of consumption to permanent and transitory changes in income etc. Fig. 6.05 Consumption tomorrow Temporary vs. permanent income change D´ Temporary: R to R´ D Permanent: R to R´´ A´´R´´ Y2´ Y2 0 R´ A´ A=R Y1 Y1´ B B´ B´´ Consumption today PIH and LCH (2) • In the life cycle model, aggregate consumption derived from behaviour of individual consumers (of different ages) with finite lifespans. • Consumption smoothing and the life cycle pattern of income mean that the young borrow, the middle aged save and the retired dis-save. • Obviously, aggregate consumption depends positively on population and income growth. • The level of savings also depends on length of retirement relative to length of working life. Stochastic Income & Interest Rates • Solved-out consumption functions useful e.g. c1 = k(r)W where wealth W = a0(1+r) + y1 + y2/(1 +r) +…. and k(.) is a known function of the real interest rate r. • Difficult to derive exact results in PIH-LCH model when income and interest rates are random. • Interest rates often assumed constant and point expectations of future income used. • Hall’s (1978) insight – look at Euler equation. Hall’s Consumption Equation • The stochastic Euler equation for the infinitely lived representative consumer is: u'(c1) = E1(1+r1)u'(c2) where Et is the conditional expectation at time t given the information set It. • Aside: Can rearrange Euler equation to get pricing kernel / stochastic discount factor. • Rational expectations assumed. When Does Consumption Follow A Random Walk? • Under very special and unrealistic assumptions, Euler equation implies that consumption is a random walk. • When u(c) is quadratic and = 1/(1+r), then ct = ut with Et(ut|It) = 0 so both ct and ut are innovations (unpredictable). • Since Et(ct|It) = 0, Et(ct|It) = ct-1. Stochastic Euler Equations (1) • Hall’s Euler equation is only a FOC, as noted already. • It does not tell you anything about the effects of income shocks, uncertainty etc. • To examine these sorts of issues, you need to embed it in a bigger model! • This is one reason why some argue that approximate solved out consumption functions are more useful. Stochastic Euler Equations (2) • Assuming CRRA preferences, joint normality of rt and ct etc., the best we can do is: Etlnct = (ln )/γ + rt/γ+½(σct)2/γ which shows that uncertainty increases savings (since ct rises and ct-1 falls as the variance of ct rises). • Long list of assumptions – rational expectations, representative agent, no credit constraints etc. Testing Consumption Euler Equations • Consumption Euler equations do not fare very well empirically. • For example, if the basic model is correct, then variables in the information set at time t-1 should not help in predicting lnct. • A natural test of this hypothesis is to include the prediction of lnyt, using variables dated t-1. or even t-2, in the regression of lnct on a constant, rt and a proxy for (σct)2. • Predicted income growth is always highly significant. Solved Out Consumption Function for US • See separate note for example of solved out consumption function for US. • Source: Muellbauer (1994), Consumers Expenditure, Oxford Review of Economic Policy. Summary (1) • Rational consumers attempt to smooth consumption over time, by borrowing in bad times (or when young) and saving in good times (or in middle age) . • Consumption is primarily driven by the present discounted value of current and future nonlabour income and initial assets. • Financial market imperfections generate credit constraints. Current income matters more for credit constrained consumers. Summary (2) • The effect of a change in the real interest rate is ambiguous since wealth effects differ for lenders & borrowers. Overall the effect is probably small and negative. • Over the life cycle, consumption is smoothed by borrowing when young, saving in middle age and dis-saving when retired. • Temporary changes in income (or other disturbances) have small effects. Permanent changes or shocks have large effects.