File - Jeffrey Landau

advertisement

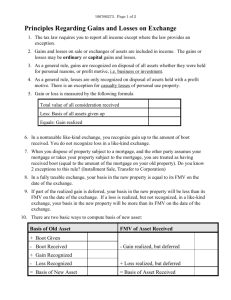

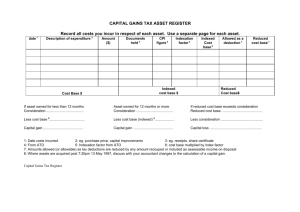

Property Transactions: Determining Gains and Losses Jeffrey Landau Acct 4641 Dr. Joseph M. Hagan Table of Contents I. II. III. Introduction……. 1 Realization Vs. Recognition……. 2 Seller-Financed Sale……. 3 A. Installment Sales Method….. IV. V. Capital Gains and Losses….. 4 B. Capital Loss Limitation….. 4 C. Carrybacks and Carry forwards….. 4 D. Capital Gain Tax Treatment….. 4 Disposition of Noncapital Assets…. 5 B. Real or Depreciable Property….. 5 1231 Assets….. Other Property Dispositions….. 5 6 6 B. Foreclosure….. 6 Related Party Transactions….. Nontaxable Exchanges….. 7 7 8 A. Like-Kind Exchanges….. 8 B. Involuntary Conversions….. 8 I. II. IX. 5 A. Abandonment and Worthlessness….. A. Disallowance of Losses….. VIII. 5 A. Inventory, Accounts Receivable, Supplies….. C. Depreciation Recapture….. VII. 3 A. Define Capital Asset…. I. VI. 3 Casualty and Natural Disaster….. 8 Eminent Domain….. 8 C. Formation of Business Entities….. 9 D. Wash Sale….. 9 Conclusion…. 9 Introduction Every single day a property is either disposed of or being acquired. Whether it be a business relieving an asset in exchange for a certain type of stock in a company; a person donating their car to a nonprofit charitable organization; or even a farmer who decides he wants to trade some of his own cattle for another farmer’s cattle. All of these transactions have to be accounted for correctly and accurately. For those taxpayers disposing of these various assets during the tax year, there is a multistep process on determining the tax consequences of such dispositions. “First, the taxpayer computes the gain or loss realized on each asset disposition and the amount of the gain or loss recognized in the current year. Second, the character of the recognized gain or loss must be identified.” Character is a critical component in determining the impact that property transactions ultimately have on taxable income or tax liability. If a transaction is characterized as a gain it can be taxed at a preferential tax rate, from the sale of capital assets, or at a taxpayer’s ordinary rate. On the other hand, when a transaction is recorded as a loss the capital losses can be deducted against capital gains, whereas ordinary losses are fully deductible against any type of income. Occasionally, depending on their market segment, a firm may choose to become a corporation or a partnership in order to take advantage of such gain and loss recognitions. Being able to determine gains and losses are extremely essential in the business community because they can quite possibly make, or even break, a company in some cases. This is due to the fact that certain types of dispositions allow for the old basis of the outlying asset to remain in the hands of the seller until the asset is disposed of at a later date, which only then they will have to recognize the income. Realization Vs. Recognition Realization and recognition are two very closely related terms. Though, in order for a business to succeed and stay on good terms with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), they must be able to distinguish between the two. The Internal Revenue Code specifies that gross income includes “gains derived from dealings in property”1 and allows a deduction for “any loss sustained during the taxable year and not compensated for by insurance or otherwise.”2 These two rules of the tax law allow firms to account for realized gains and losses in computing taxable income. They also reflect the realization principle of accounting which states that “increases or decreases in the value of assets are not accounted for as income. Such increases or decreases are not taken into account until an asset is converted to a different asset through an external transaction with another party.” Thus, the gain or loss realized on a property disposition is taken into account for tax purposes. This basically means that any and every realized gain or loss will become recognized at some point of conversion. The computation for disposition of property is as follows: Amount realized on disposition (Adjusted tax basis of property) Realized gain or loss ↓ Recognized gain or loss The realization principle gives property owners some important planning implications because it allows them to have some control over the timing of gain or loss recognition. For a sale or exchange, the amount realized on the disposition of property is equal to any cash received plus the fair market value (FMV) of any property received. 1 2 Section 61(a)(3) Section 165(a) Seller-Financed Sale When a purchaser promises to pay a seller cash over a specified future period rather than on the date of a sale, it is known as a seller-financed sale. “In an arm’s-length seller-financed sale the seller chargers the purchaser a market rate of interest on the note.” Generally, the seller will include the principle amount of the note in the amount realized and compute the gain and loss accordingly. A certain method of accounting used, called the installment sales method, allows for sellers to not recognize the entire realized gain in the year of sale. Instead, the seller calculates the gain recognized using the gross profit percentage, linked to the seller’s receipt of cash of the term of the purchaser’s note. The gross profit percentage is calculated by dividing the gain realized by the sale price, then multiplying that percent by the amount of each payment received. The installment sale method can be used by taxpayers to defer gain recognition on the sale of investment property and many types of business, but cannot be applied to gains realized on the sale of stocks or securities traded on an established market.3 Though the taxpayer generally benefits from the installment sale method, sometimes they may not, in which the taxpayer must make a written election not to use the method. If a taxpayer converts a note receivable to cash, than they must immediately recognize any deferred gain represented by the note.” Capital Gains and Losses A capital gain or loss results from the sale or exchange of a capital asset.4 This code section is derived from the two distinct components that define a capital gain or loss. “First, the transaction resulting in the gain or loss must be a sale or exchange. Second, the asset surrendered must be a capital asset.” If a firm disposes of a capital asset in some other way rather than a sale 3 4 Section 453(k)(2)(A) Section 1222 or exchange, the realized gain or loss would become ordinary in character. Every asset is a capital asset. That is the definition of a capital asset, as long as it does not fall under one of the following eight categories: 1. Inventory items or property held by the taxpayer primarily for sale to customers in the ordinary course of business. 2. Accounts or notes receivable acquired in the ordinary course of business. 3. Supplies used or consumed in the ordinary course of business. 4. Real or depreciable property used in business and intangible business assets subject to amortization.5 5. A copyright, literary, musical, or artistic composition; memorandum; or similar property held by a taxpayer whose personal efforts created the property or person to whom the property was gifted by the creator. 6. Certain publications of the U.S government. 7. Commodities derivative financial instruments held by a dealer. 8. Hedging transactions properties. When it comes to capital gains and losses the federal income tax system has a subset of rules that apply. One of those rules is the capital loss limitation. It states: Capital losses can be deducted only to the extent of capital gains.6 More easily understandable, “if the combined result of all sales and exchanges of capital assets during the year is a net loss, the net loss is nondeductible. If the combined result is a net gain, the net gain is included in taxable income.” Individuals are permitted to deduct up to 3000 dollars annually for capital losses in excess of capital gains. 5 6 Reg. Section 1.167(a)-3 and Section 197(f)(7) Section 1211 Coming across a capital loss for an individual or corporation may not be so terrible due to the loss carrybacks and carry forwards. A nondeductible net capital loss incurred by an individual is carried forward indefinitely.7 This means an individual recognizes a net capital gain, in excess over the capital loss, the loss carry forward is deductible to the extent of the gain. A net capital loss incurred by a corporation is carried back three years and forward five years, but only as a deduction against net capital gain recognized during the eight-year period.8 Disposition of Noncapital Assets All disposition of inventories, accounts and notes receivable and supplies are fairly straightforward and treated as ordinary income. As for land, it has to be determinable by the IRS that the land was not acquired primarily for sale to customers in order for it to be considered a capital asset. The only difference for accounts receivable is whether the firm uses the accrual or cash method. Accrual basis firms realize ordinary income from transactions in the form of receivables, which creates a tax basis equal to the face value of the receivable. Cash basis firms, alternatively, do not realize ordinary income until they collect the cash, therefore their tax basis in the unrealized accounts receivable is zero. A complicated category of noncapital assets are real or depreciable property such as rental real estate, and intangible business assets such as purchased goodwill. The gains and losses on the sale of these noncapital assets are recognized as ordinary in character if they are held for a year of less. If the holding period exceeds one year, the gain or loss is characterized under the Internal Revenue Code Section 1231, otherwise known as the Section 1231 asset. The rule states that if the combined result of all sales and exchanges of Section 1231 assets during the year is a 7 8 Section 1212(b)(1) Section 1212(a)(1) net loss, the loss is treated as an ordinary loss. On the other hand, if the result is a net gain, the gain is treated as a capital gain.9 There is a pro-business rule applied to Section 1231 that modifies recognition of gains on the sale of depreciable property. It merely changes the character of gain on the sale of Section 1231 property; it does not create additional gain. Depreciation recapture is that name of the rule and it contains three components: full recapture, partial recapture, and 20 percent recapture. Full recapture, or Section 1245 recapture, dictate that an amount of gain equal to accumulated depreciation or amortization through date of sale is recharacterized as ordinary income.10 This prohibits the conversion of ordinary income into capital gain. Partial recapture, or Section 1250 recapture, is a concept in which only accelerated depreciation in excess of straight-line depreciation is recaptured. This rule applies to gains recognized on depreciable realty such as buildings, improvements, and other permanent attachments to land. “Twenty percent recapture is particularly in significant for sales of buildings placed in service after 1986.” Other Property Dispositions If a firm formally relinquishes its ownership interest in an asset, any unrecovered basis in the asset represents and abandonment loss.11 An abandonment loss is and ordinary deduction even if the asset was capital or Section 1231 because the loss is not realized on a sale or exchange. An owner will realize a loss equal to the owner’s basis before abandonment and treated as if the assets were sold at a price of zero. If a company owns securities in an affiliated corporation than the can treat the securities as a noncapital asset and full deduct the loss since it is not subject to the capital loss limitation. 9 Section 1231(a)(1) Section 1245 and Section 197(f)(7) 11 Regs. Section 1.165-1(b), Section .165-2, and Section 1.167(a)-8 10 Another form of property disposition is from casualty and thefts. These are unfortunate, destructive events that occur such as a fire, flood, earthquake, or some act of nature, or through human vandalism, theft, or riots. Firms usually are insured in case such tragedies like these occur, but if the insurance reimbursement is less than the adjusted basis of the destroyed property, the firm can claim the unrecovered basis as an ordinary deduction.12 Though if the reimbursement exceeds the adjusted basis, the firm must recognize the excess as taxable income. Related Party Transactions Related party transactions occur when two parties of some relation, for example a father and son, engage in a transaction. It may even be a business who plans on selling a piece of equipment to their wholly owned subsidiary. The Internal Revenue Code defines related parties as “people who are members of the same family, and individual and a corporation if the individual owns more than 50 percent of the value of the corporation’s outstanding stock, and two corporations controlled by the same shareholders.”13 Since there is such a wide array of relationships among businesses, Congress has to set standards that will not allow related parties to purchase and sell assets to each other in order to avoid paying taxes. One such regulation is that in which Congress states losses realized on the sale or exchange of property between related parties are nondeductible.14 There are two general rules for why the tax law disallows losses on related party sales: the theory that the related party loss may not represent an economic loss to the seller, and the fact that related party transactions occur in a fictitious market in which seller and purchaser may not be negotiation at arm’s length. Due to the fictitious market, the government has no assurance that the market value of an asset is equal to the sale price. Though, 12 Reg. Section 1.165-7(b) Section 267(b)(1) 14 Section 267(a)(1) 13 if a purchaser subsequently sells property acquired in a related party transaction and realizes a gain, the purchaser can offset this gain by the previously disallowed loss.15 Nontaxable Exchanges “No gain or loss shall be recognized on the exchange of property held for productive use in a trade or business or for investment if such property is exchanged solely for property of likekind which is to be held either for productive use in a trade or business or investment.”16 This allows firms to withhold any tax costs from converting one asset to another with the same function or purpose. Some examples of like-kind property are: automobiles and taxis, airplanes and helicopters, office furniture and copying equipment, and livestock of the same sex. When a party receives cash in exchange for a like-kind property that may not be of market value as the other property, the party receiving the payment must recognize it as a relief of debt treated exactly like cash received. Occasionally properties may be disposed of involuntarily. It can either be because of a natural disaster or a condemnation of private property by a government agency that takes the property for public use. In either case, a taxpayer that realizes the gain on involuntary conversion of property can elect to defer the gain if two conditions are met.17 First, the taxpayer must reinvest the amount on the conversion into a property similar or related in service or use. Second, the replacement of the involuntarily converted property must occur within the two taxable years following the year the conversion took place. In the formation of business entities, no gain or loss is recognized when property is transferred to a corporation solely in exchange for that corporation’s stock if the transferors of 15 Section 267(d) Section 1031 17 Section 1033 16 property are in control of the corporation immediately after the exchange.18 The term property in this context is defined as cash, tangible, and intangible assets, not personal services. In order for this nontaxable exchange to occur, the transferors of property must own at least 80 percent of the corporation’s outstanding stock immediately after the exchange. Corporations that issue stock in exchange for property never recognized gain or loss on the exchange, regardless of whether the exchange is nontaxable or taxable to the transferor of the property.19 Lastly, a non-typical nontaxable type of exchange that defers only the recognition of losses realized on certain sales of marketable securities,20 is known as a wash sale. A wash sale occurs when an investor sells securities at a loss and reacquires basically the same securities within 30 days before or 30 days after the sale.” If the rule applies, the cost of the reacquired securities is increased by the unrecognized loss realized on the sale.” Conclusion Determining gains and losses on property transactions can seem to be intensive, strenuous, and confusing. As discussed, there are a tremendous amount of different ways to realize, recognize and ultimately report income. Taking advantage of those ways, correctly, is key. That is why Congress has put in place a tax system that requires individuals and businesses to comply with their rules and regulations. The system is not set up to make all businesses successful, but those who can regulate their gains and losses accordingly, will succeed. 18 Section 351 Section 1032 20 Section 1091 19 Footnotes/Endnotes Section 61(a)(3) Section 165(a) Section 453(k)(2)(A) Section 1222 Reg. Section 1.167(a)-3 and Section 197(f)(7) Section 1211 Section 1212(b)(1) Section 1212(a)(1) Section 1231(a)(1) Section 1245 and Section 197(f)(7) Regs. Section 1.165-1(b), Section .165-2, and Section 1.167(a)-8 Reg. Section 1.165-7(b) Section 267(b)(1) Section 267(a)(1) Section 267(d) Section 1031 Section 1033 Section 351 Section 1032 Section 1091 Bibliography Campbell, A. D (2010). Determining the amount and character of gain or loss on sale of real estate. Practical Tax Strategies, 85(2), 73-79. Retrieved from http;//search.proquest.com/docview749399404?accountid=10639 Gains and Losses. (2011). Retrieved from IRS: http//www.irs.gov/publications/p225/ch08.html Jones, S. M., & Rhoades-Catanach, S. (2013). Principles of Taxation for Business and Investment Planning. McGraw-Hill Revenue Recognition. (2013). Retrieved from Accounting Standards Codification: http://asc.fasb.org/topic&trid=2197195&nav_type=left_nav&analyticsAssetName=secti on_page_left_nav_topic Sale of Property. (2012). Retrieved from IRS: http://www.irs.gov/publications/p17/ch14.html Taxation Issues- Calculating Gains and Losses. (n.d.). Retrieved from Investopedia: http://www.investopedia.com/exam-guide/finra-series-6/taxation-issues/calculatinggains-losses.asp#axzz2Ly4r69vv