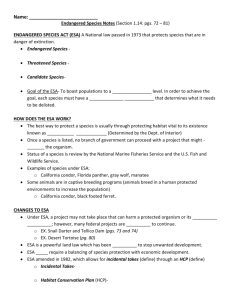

The Law and Politics of Federal Wildlife Preservation

advertisement

The Law and Politics of Federal Wildlife Preservation Dean Lueck Introduction Until the Endangered Species Act of 1973, wildlife preservation was relatively uncontroversial. Since the ESA, wildlife law has been a contentious battleground in law and politics. 2 Key Concepts There is an economic rationale for federal wildlife preservation based on transaction costs and incomplete property rights. The ESA has placed property rights to wildlife up for grabs and has lead to extensive “claiming” activity. Perverse Incentives: landowners have destroyed potential wildlife habitat to avoid costly land-use restrictions under the ESA. “shoot, shovel, and shut-up” 3 Problems with Wildlife Protection Problems with wildlife preservation stem from imperfect property rights and high costs of private contractual solutions. The main finding is that the costs of protecting wildlife on private land are borne primarily by a small group of landowners. 4 II. The History of Federal Wildlife Preservation The federal government’s role in wildlife protection begins with the Lacey Act of 1900. Prior to 1900, states regulated wildlife by limiting taking and trading to protect this open-access resource. States established departments of fish and game, hiring game wardens to enforce game laws. 5 Federal Protections The Lacey Act—a response to the demise of the passenger pigeon—authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to preserve, protect, and restore game birds and other wild birds. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 ratified the 1916 treaty with Canada to protect migratory birds. 6 Extending Federal Protection Federal government began establishing and managing wildlife refuges (Pelican Island Florida, 1903). The Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act of 1934 req’d waterfowl hunters to purchase an annual “duck stamp,” generating millions of dollars for habitat acquisition. 7 Wildlife Management The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1964 established funds for acquisition “for any national area which may be authorized for the preservation of species of fish and wildlife that are threatened with extinction.” The Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 gave the Secretary of Interior broad authority to protect species. 8 Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 The ESPA authorized the Secretary of Interior to purchase habitat to protect endangered species and to list species threatened with extinction. The act prohibited the taking of endangered species on federal wildlife refuges. Also, it required federal agencies to consider the effects of its programs on endangered wildlife. 9 Endangered Species Act of 1973 The ESA fundamentally changed the role of the federal government in wildlife issues. It expanded federal authority and dramatically changed the way endangered species would be managed. Secretary was required to list endangered and “threatened” species. Made it unlawful to take species whether on private or public land. 10 Additional Provisions Take was broadly defined to mean “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect.” Federal agencies must not jeopardize any listed species or modify critical habitat. A citizen-suit provision to force the secretary to follow the law. Federal authority extended into the management of resident wildlife traditionally held by states. 11 Broad Reach of ESA Amendments, court decisions, and regulatory interpretations define the current ESA. Habitat modification is considered a taking Landowner groups have demanded that they be compensated for the lost value of property when certain uses are prohibited in order to protect habitat. 12 Modifying ESA Safe Harbor allows landowners—who through their conservation efforts have attracted listed species—to develop land if the species population remains above an established base-line. No Surprises prohibits the FWS from adding land-use restrictions or additional financial burdens on a landowner with an authorized habitat conservation plan. 13 Property Rights and Wildlife Preservation An economic model of wildlife preservation can illuminate the behavior of landowners, environmental groups, politicians, and bureaucrats. Landowners tend to have better information than the FWS about habitat and populations of listed species. 14 The Model Model assumes two competing uses of a plot of land: wildlife habitat and non-wildlife uses. When the marginal values in the competing uses are equal, then the value of land will be maximized. The first-best outcome is at L*. 15 16 The Contracting Problem: High Transaction Costs The landowner may not be able to capture the value of providing habitat for wildlife. His small plot essentially makes wildlife an openaccess resource. If the landowner captures no benefit from wildlife habitat, he chooses to allocate all his x land to non-wildlife use—L . 17 Too Little Wildlife Habitat The small landowner sets aside too little habitat resulting in a deadweight loss given by the triangle x BCL . this loss also represents the gains from a contract among a group of landowners who can effectively control the amount of habitat needed for the wildlife to thrive. In the case of public ownership, the misallocation results when the agency subsidizes the non-wildlife use of the land. E.g., “chaining” 18 Chaining “This is an extremely simple operation and merely involves pulling a large chain by two tractors. It may be used in light scrub that is easily crushed, and heavy trees among which there is not much undergrowth.” 19 20 21 Collective Action to Provide Habitat Before the ESA: Pay-to-Protect The FWS purchases wildlife habitat from the landowner. If the FWS sets the price correctly (P*), the solution is identical to the first-best solution in Figure 1. ESA: Land-Use Regulations The ESA prevents land-use modification, meaning that landowner will have to set LESA aside. This allocation has a deadweight loss associated with too much habitat provision shown by triangle ABLESA. 22 Habitat Acquisition The pre-ESA regime of pay-to-protect will tend to provide too little habitat, but first-best can be approached through a program of habitat acquisition. The post-ESA regime can, in principle, also approach first-best, but this ignores the behavior of interest groups in response to the incentives under the ESA. 23 Claiming Land under the ESA Once a species is listed, the land that provides habitat for a listed species comes under the control of the FWS. The landowner loses both the use of and income from the land. Because the ESA allows citizen lawsuits, environmental groups can sue for listing, thereby claiming land by removing it from non-wildlife uses. 24 No Limits The ESA places no limits on the number of species that can be listed or the number of acres to be affected. If the FWS had to pay for habitat acquisition, a budget constraint would limit acquisitions to those properties that provided the highest marginal returns. Groups can claim large areas by seeking to list species that inhabit large areas, impeding those land-use actions that harm the species. 25 Claiming Public Lands Historically, many public lands have been managed for single uses—timber harvesting or grazing—because of the political power of strong interest groups. The ESA can provide a mechanism for environmentalists to attack what they regard as pork-barrel projects that lower environmental quality. Environmentalists used the northern spotted owl to stop timber cutting in old growth forests. 26 Claiming Land: Preemption and Political Action The landowner maintains important influence over the land by virtue of control over nonwildlife uses. The static model does not fully capture the actions of landowners facing potential ESA restrictions. The landowner may be able to take action to prevent the administration of the ESA. 27 Thwarting the Implementation of the ESA If the species is already present but unknown to the FWS, landowners may kill all listed species inhabiting their property. “shoot, shovel, and shut-up” If the species is not yet present but the potential for inhabitance is high, landowners may destroy habitat in order to preempt ESA regulations. Preemption can be examined using a two-period model. 28 Two-Period Model The landowner can chose to maintain or destroy habitat in period 1. Destroying habitat has a one-time cost CD and generates benefits BD from development (timber harvest). CD is the cost of premature development, such as foregone revenue from harvesting timber before it is financially mature. The FWS moves in period 2. If it finds a listed species, the payoff to the landowner is zero. 29 30 Choosing Preemption In a dynamic model, landowners have incentive to decrease the amount of wildlife habitat, even compared to that without the x ESA (not even L is provided). Without habitat the population of the listed species declines because the amount of land allocated to habitat declines under the ESA. 31 Other Implications If permits are required for development, then killing species becomes more attractive to landowners. Paying landowners will reduce the payoff from preemption. Increase in the probability of listed species detection in period 2 will increase the likelihood of preemption. Risk-averse landowners will preempt more often than risk-neutral landowners. 32 Behavior under the ESA The ESA as an exogenous transformation of rights To the extent that government regulation is funded by wildlife users and compensate landowners for landuse changes, collective action will have broad support and little contention. The ESA promised wide-spread benefits at a trivial cost. Congress could not have foreseen the judicial and administrative expansion of the ESA. 33 Interest Group Behavior ESA has altered the incentives of many people and institutions, most notably environmentalists, private landowners, the FWS, public land agencies, scientists who get paid to find listed species, and lawyers and politicians. 34 Environmental Groups Environmental groups can force the FWS to act by showing that federal agencies or private land uses are harming listed species. Environmental groups can encourage the listing of new species that inhabit land for which environmentalists desire to change existing or planned land use. Environmentalists can either petition or sue the FWS for not acting swiftly. 35 Environmental Groups, cont’d Environmentalists have successfully use the citizen lawsuit provision to invoke and strengthen the ESA. By forcing federal agencies to change their land management practices, millions of acres have been de facto set aside as refuges for listed species. The ESA has given environmentalists a strong claim over private lands. E.g., northern spotted owl, and black-tailed prairie dog? 36 Landowners The ESA represents an uncompensated transfer of rights to their land. Preemption model predicts habitat destruction. Landowners have incentives to reclaim these rights through both private and public action. Safe Harbor and No Surprises policies mitigate the harm caused to landowners by the ESA. 37 The FWS The FWS enjoys expanded powers under the ESA, but must be cautious not to alienate long-lived constituents. Before the ESA, the FWS had served a hunting/fishing constituency. Since the ESA, the FWS serves a nonhunting, environmentalist constituency. 38 Public Land Agencies Since TVA (the snail-darter case), federal agencies have been forced to enhance the conservation and restoration of list species. Timber harvesting and grazing activities have declined, and water development projects have been eliminated or reduced in scale. 39 Three Case Studies Takeovers of Public Land by Environmentalists: The Northern Spotted Owl Preemptive Habitat Destruction on Private Land: The Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Wildlife Restoration before and after the ESA 40 41 The Northern Spotted Owl In 1990, the owl was listed as a threatened species. Nearly 11 million acres of public forests in California, Oregon, and Washington were set aside as crucial habitat. Annual timber harvests from public lands has declined dramatically. 42 43 44 45 46 The Red-Cockaded Woodpecker RCWs—listed in 1969—reside in longleaf pine ecosystems ranging from Virginia to Arkansas. Cost of foregone timber harvests for a single RCW colony can be as much as $196,107. A forest landowner has an incentive to preemptively harvest timber. 47 48 RCWs cont’d Ben Cone’s confrontation with the FWS. The closer a plot is to RCWs, the higher the probability that the plot will be harvested, even if the trees are younger than when trees are normally harvested. Timber at high risk sites is harvested 9 years earlier than the average age of 47.9 years. Population of RCW continues to decline despite being listed for 37 years. http://www.taemag.com/issues/articleID.168 92/article_detail.asp 49 How Many RCWs? Estimated Population: There are currently about 5,000 groups of red-cockaded woodpeckers -- or roughly 12,500 birds -- throughout their range, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2000. Currently, there are an estimated 14,068 red-cockaded woodpeckers living in 5,627 known active clusters across eleven states (Jan 2003). Despite protection, all monitored populations (with one exception) declined in size throughout the 1970's and into the 1980's. In the 1990's, in response to intensive management based on a new understanding of population dynamics and new management tools, most populations were stabilized and many showed increases. 50 Wildlife Restoration Before and After the ESA Populations of many wildlife species fell to alarming low numbers before dramatic recoveries long before the ESA. Unlike the regulations inherent in the ESA, landowners were never penalized for altering habitat, thus the preemption incentive was absent. 51 The Record before the ESA Recoveries in many species have been impressive and provide keys to success: Season closures were enforced and game trade was restricted. Habitat was enhanced through refuges, especially for migratory waterfowl. Animals were live captured, raised in captivity, and released in depleted areas. Landowners often supported these efforts. 52 The Record Under the ESA Only 24 species have been de-listed. Seven were de-listed because they were extinct, and nine because of data errors. Eight were considered “recovered” None of these eight recoveries is because of the ESA. The alligator should never have been listed. Improving status of the bald eagle is due to the ban on DDT and enforcement against poaching— neither unique to ESA policies. 53 Conclusion Under the ESA no dramatic species recoveries can be claimed. The ESA has been a double-edged sword for environmentalists. It has given them great sway in the use and management of public lands. But habitat is being destroyed and species are losing ground on private lands because of the perverse incentives under the ESA. 54 Additional Reading Richard L. Stroup, “Making Endangered Species Friends Instead of Enemies,” Work! September/October 1995 Issue, http://www.taemag.com/issues/articleID.1689 2/article_detail.asp Richard Stroup, “Endangered Species Act: Making Innocent Species the Enemy,” PERC Policy Series Issue Number PS-3, April 1995 http://www.perc.org/perc.php?id=648 55