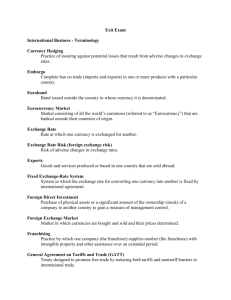

This is why debt instruments [promissory notes] do not mention

advertisement

![This is why debt instruments [promissory notes] do not mention](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009452283_1-0aaee31df20ae6cde6fa1aafdd3efab3-768x994.png)