Toolkit 1: purposes and types of regulation (DOCX 465kb)

advertisement

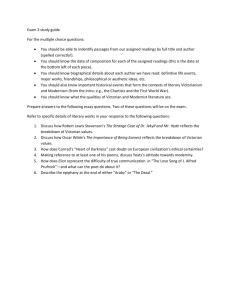

Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014 Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation The Secretary Department of Treasury and Finance 1 Treasury Place Melbourne Victoria 3002 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9651 5111 Facsimile: +61 3 9651 5298 www.dtf.vic.gov.au Authorised by the Victorian Government 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne, 3002 © State of Victoria 2014 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Treasury and Finance logo. Copyright queries may be directed to IPpolicy@dtf.vic.gov.au ISBN 978-1-921831-51-5 Published August 2011 If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format please email information@dtf.vic.gov.au. This document is also available in PDF format at www.dtf.vic.gov.au An appropriate citation for this publication is: Government of Victoria, 2011, Victorian Guide to Regulation, Department of Treasury and Finance, Melbourne. Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Contents 1. Purposes and types of regulation .............................................................1 1.1 Rationale for government intervention............................................................................. 1 1.2 Characteristics of good regulatory systems....................................................................... 4 1.3 Types of regulatory regimes .............................................................................................. 6 Attachment 1. Maintaining Consistency with the Australian Consumer Law ....18 Background .............................................................................................................................. 18 Victoria’s approach to maintaining IGA consistency ............................................................... 19 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation i 1. Purposes and types of regulation This toolkit provides policy context, examines regulatory options, and addresses the following issues: Under what circumstances should governments consider intervening in the market (Section 1.1)? What are the characteristics of ‘good’ government regulatory systems (Section 1.2)? What are the different types of regulatory regimes (Section 1.3)? What are the different forms of government regulation (Section 1.3)? 1.1 Rationale for government intervention Traditionally, government intervention in markets is justified on economic efficiency grounds, or to achieve social and environmental objectives. From an economic perspective, freely functioning markets generally provide the most efficient means of allocating goods and services between members of the community so as to maximise the well-being of the community. The market mechanism is also generally the best means of ensuring that a good or service is produced efficiently. In addition to these allocation and production efficiencies, competitive markets encourage innovation and greater consumer choice, thereby maximising society’s economic welfare. Addressing market failure In some instances, the market does not deliver the best outcomes for society – for example, because of the existence of market distortions or imperfections. In such cases, the market is said to be ‘failing’ and, in some circumstances, government intervention may be justified on the grounds that economic outcomes could be improved. Major causes of ‘market failure’ include: External costs and benefits, commonly referred to as externalities or spillovers – which occur when an activity imposes costs (which are not compensated) or generates benefits (which are not paid for) on parties not directly involved in the activity. Without regulation, the existence of externalities results in too much (where external costs or negative externalities occur) or too little (where external benefits or positive externalities arise) of an activity taking place from society’s point of view. Pollution is the most common example of a negative externality, while immunisation against a contagious disease is an example of an activity that generates a positive externality. Insufficient or inadequate information. Consumers may not have adequate access to the information they require to make decisions that are in their best interests. For example, consumers need access to information on the quality or content of products (including associated hazards). Sometimes, sellers may have access to better information than buyers (often referred to as ‘information asymmetries’). Under such circumstances, governments may regulate to require information disclosure, to provide the information directly, or place restrictions on the supply of goods or services regarded as dangerous. Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 1 Public goods – are goods or services which display both the following characteristics: – they are non-excludable, which means that anyone can have access to them once they are provided; and – they are non-rivalrous, which means that any person can benefit from them, without diminishing anyone else’s enjoyment. National defence and street-lighting are commonly cited examples of public goods. Once provided, the benefits of public goods can be enjoyed by all parties, although it is not feasible to charge all users for these goods. As a result, public goods may not be provided, or will be under-provided, unless governments intervene. The existence of overwhelming market power – which may arise from uncompetitive market structures (e.g. a monopoly or a small number of market participants) or from anti-competitive conduct (e.g. collusion). In these circumstances, prices may be higher or output lower than they should be, and too few resources are allocated to the production of particular goods and services. In other words, the market does not produce enough of what best meets society’s needs. Regulation may be required to ensure this market power is not exploited to the detriment of consumers. Addressing social welfare objectives In addition to addressing market failure, government intervention may be justified in the pursuit of social and equity objectives. Such objectives include the redistribution of income to achieve equity goals; establishing law and order; cultural objectives; and preserving and protecting environmental resources. Key rationales for government intervention of this kind are as follows: Governments generally achieve redistributive goals through the taxation and social security systems. It is a widely held belief that every individual should have access to at least some minimum level of income – hence, taxes are collected and partially redistributed to those who are economically disadvantaged. In addition, there is a strong view within the community that certain goods and services are fundamental or essential and should be provided free of charge to all (or, at least, at concessional rates to those most in need). This helps to explain why governments typically provide financial support for education and health services. Regulations may also be imposed to assist in the policing of crimes or to reduce the risk of criminal activity. Thus, persons in certain occupations may be required to keep detailed records of transactions to assist police in apprehending and prosecuting suspected criminals. Other social policies include human rights, protecting the vulnerable and disadvantaged, and relieving geographic and social isolation (e.g. by ensuring adequate community facilities and the appropriate provision of infrastructure). Addressing the management of public risk A particular form of social regulation relates to requirements that seek to reduce or manage the risk of harm to health, safety or welfare of individuals or the community. Sometimes referred to as ‘protective’ regulation, it includes: measures to promote public health and safety – examples include occupational health and safety regulations, which seek to reduce the incidence of injuries and deaths in the workplace; and regulation of product and home safety (e.g. electrical safety standards), which seeks to reduce the risk of accidents causing injury; 2 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation reducing the risk of harm to vulnerable sections of the community – examples include regulation of minimum quality standards in childcare and supported residential services, which seeks to protect children and aged care residents from poor care; and restrictions on the practice of certain occupations and professions – such as health services, which seek to protect consumers from risky practitioners. It is not possible for governments to provide a completely ‘risk-free’ society, or to prevent every possible event that might cause harm. While, in many cases, risk regulation will have large and important benefits, the direct and indirect costs imposed by regulatory approaches may not be as immediately obvious. Moreover, it needs to be recognised that regulation consumes scarce resources. Risk regulation that is poorly targeted or costly will divert resources from other priorities. Conversely, appropriately targeted regulation enables the direct and/or indirect pricing-in of the market failure by the agent being regulated. The decision of when it is appropriate to intervene in the market to reduce or manage public risk is a challenging one. Even in these situations, the underlying reasons for which these risks arise and are not dealt with in the market still need to be analysed - just as with other areas of regulation. For example, restrictions on medical practice in part aim to address problems arising from information asymmetries. Framing the problem in this way allows a more targeted and commensurate response to the problem to be developed. Moreover, as discussed below, risk assessment can be a particularly valuable tool to assess whether a proposal represents a high priority for government intervention to manage public risks. Risk assessment Any problem identified as potentially requiring government intervention will have an element of risk attached to it. Risk refers to the probability that existing hazards will cause harm – i.e. that an undesirable event will occur. For example, measures to address occupational health and safety issues recognise that there is risk of an accident happening in the workplace. Risk analysis is the process of discovering what risk is associated with a particular hazard, which involves identifying hazards and the mechanisms that cause them, and estimating the probability that they will occur and their consequences. As illustrated in Figure 1 below, the ‘level’ of risk can be assessed by combining the consequences of an adverse event occurring and the likelihood or probability that these impacts will occur (while recognising that there may be a degree of uncertainty surrounding such assessments). In assessing the consequences, consideration needs to be given to the size of the population likely to be affected, and the severity of the impact on those affected. This will provide an indication of the aggregate effect of an adverse event. For example, ‘major’ consequences may include significant harm to a small group of affected individuals, or moderate harm to a large number of individuals. Likelihood Figure 1: Assessing the level of risk High Mod Low Medium risk Low risk Low risk Low High risk Medium risk Low risk Moderate High risk High risk Medium risk High Consequence Risk analysis is a valuable tool in addressing the threshold issue of whether or not governments should intervene. It can help to determine: whether the risks that government intervention is intended to address are of significant magnitude compared with other risks; and Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 3 the extent to which government intervention reduces the initial risk problem (i.e. the effectiveness of the proposed government response). When combined with an assessment of the extent to which markets fail to manage these risks efficiently, or in line with social goals, and the net cost of the proposed regulation (relative to other approaches), risk analysis can be used to assess the level of priority for government regulation. Table 1 provides an illustration of how this might be done. Table 1: Assessing the priority for government intervention – an illustration Problem Level of risk Extent of market failure Effectiveness in addressing problem Cost Priority A B C D High Moderate Medium Major Low Minor High None Low High High Low High Low Medium High Low Medium High Low There may be little justification for government intervention where: the likelihood of a particular problem occurring is very small – where the effects of an adverse effect would be low to moderate; or the level of risk is relatively high, but the capacity of regulation to address it in a cost effective way (i.e. effectiveness or expected net benefits) is low. In other words, efforts at reducing risks are best directed to areas where gains are greatest and the risks are regarded as unacceptable (e.g. regulation of major hazard facilities), rather than cases where efforts will generate only modest gains. Risk assessment enables decisions to be made about government regulation to ensure it is in proportion to the risks involved. The objective of implementing a proposal to deal with risk should not be to reduce the risk at all costs, or to reduce it to a minimum level, but rather to balance the marginal benefits and costs to society of lowering the risk. 1.2 Characteristics of good regulatory systems While government regulation is sometimes necessary to achieve certain economic, social and environmental goals, excessive or poorly developed regulation can impose costs on business and the community that outweigh the benefits of this regulation. These costs can have negative implications for overall economic performance, including employment and investment opportunities. To avoid the problems caused by poorly designed regulation, the Victorian Government has given a high priority to regulatory reform. This is based on the premise that government should not resort to explicit regulation unless it has clear, continuing evidence that: a problem exists; government action is justified; regulation (i.e. in the form of primary or subordinate legislation) is the best option available to government; and (where regulation is justified) the regulatory model chosen addresses the policy objectives at least cost (relative to other options) to businesses and the community. Once a positive argument for government regulation has been established, it is important that the nature of the regulation meets the following key characteristics: Effectiveness. Regulation, in combination with other government initiatives, must be focused on the problem and achieve its intended policy objectives with minimal side 4 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation effects. The regulatory system should also encourage innovation and complement the efficiency of markets. Proportionality. Regulatory measures should be proportional to the problem that they seek to address. This principle is particularly applicable in terms of any compliance burden or penalty framework which may apply. This characteristic also includes the effective targeting of regulation at those firms/individuals where the regulation will generate the highest net benefits. This would include risk-based approaches whereby different burdens are imposed within a regulatory regime depending on the assessed risk of regulated entities. Flexibility. Government departments and agencies are encouraged to pursue a culture of continuous improvement, and regularly review legislative and regulatory restrictions. Where necessary, regulatory measures should be modified or eliminated to take account of changing social and business environments, and technological advances. All subordinate legislation must be reviewed regularly and systematically under the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994. The Act mandates that subordinate legislation ‘sunsets’ after 10 years. This should be considered as the maximum time period at which the legislation is reviewed. Best practice would require more frequent review periods (although overly frequent changes in the law can place burdens on the community). Flexibility should also be taken into account when drafting legislation, to ensure that it does not unnecessarily constrain future government responses. For example, if primary legislation requires prices to be specified in subordinate legislation, it makes it illegal to adopt other less prescriptive options (e.g. price monitoring), even if such less prescriptive approaches become more appropriate over time. Transparency. The development and enforcement of government regulation should be transparent to the community and the business sector. Transparency can promote learning and information-sharing within the regulatory system to improve the design, administration and enforcement of regulation, and can also help to build public trust in the quality of regulation and the integrity of the process. Consistent and predictable. Regulation should be consistent with other policies, laws and agreements affecting regulated parties to avoid confusion. It should also be predictable in order to create a stable regulatory environment and foster business confidence. The regulatory approach should be applied consistently across regulated parties with like circumstances. Cooperation. Regulation should be developed with the participation of regulated parties and the community. Consideration should also be given to other jurisdictions, both within Australia and internationally, to take into account the needs to multi-jurisdictional businesses and Victoria’s major trading relationships. Regulators, in administering and enforcing regulation, should also seek to build a cooperative compliance culture. Accountability. The Government must explain its decisions on regulation and be subject to public scrutiny. The same is true of its enforcement agencies. As such, the development and enforcement of regulation in Victoria should be regularly evaluated against key performance indicators, with the results being reported to the public on a systematic basis. Subject to appeal. There should be transparent and robust mechanisms to appeal against decisions made by a regulatory body that may have significant impacts on individuals and/or businesses. Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 5 1.3 Types of regulatory regimes There are different forms of regulation and a range of other measures that government may adopt to achieve its policy objectives. It is important to ensure that the regulatory model chosen is consistent with the type of regulatory problem. Direct approach In general, adopting a direct approach to addressing an identified problem will ensure that a more efficient and effective outcome is achieved as compared with an indirect response (which, for example, may target a contributory cause of the problem). A direct approach will generally cause fewer distortions in the market, and provide a clearer indication of the objectives of the regulatory proposals. Furthermore, the most direct regulatory proposal will relate most directly to that regulatory objective, therefore minimising secondary or unintended effects. The following example (see below) indicates the weakness of adopting an indirect approach to addressing the problem of drink-driving. Tackling drink-driving – the weakness of an indirect approach (hypothetical example) An indirect approach to addressing the issue of drink-driving would be to require the early closure of all licensed premises (e.g. before 8pm). Not only would the costs of such an approach be high (e.g. loss of business to licensed premise holders), but it may induce individuals to consume alcohol more quickly than otherwise, and still drive home. This approach would also adversely affect those using the premises who are not drinking alcohol or not intending to drive home. A more direct approach would be to prevent or discourage drinkers from driving – for example, through the use of educational campaigns against drink-driving or by increasing enforcement of the legislation through increased random breath testing. Of course, these direct approaches would need to be subject to cost-benefit analysis to determine the option with the greatest net benefit. Regulatory approaches Regulation may take the form of prescriptive rules, which focus on the inputs, processes and procedures of a particular activity. For example, as part of regulation designed to reduce workers’ exposure to noise levels in a particular industry, a prescriptive measure may be to mandate the wearing of ear protection and/or prohibiting the use of certain industrial equipment. One of the main advantages of prescriptive regulation is that it provides certainty and clarity regarding what constitutes compliance. By setting out requirements in detail, it provides standardised solutions and facilitates straight-forward enforcement. However, because of its inflexibility, prescriptive regulation is unsuitable in situations where circumstances are subject to change (e.g. due to technological change) or there are feasible alternative approaches to achieve the desired outcome. Moreover, prescriptive rules often do not provide incentives for the intended outcomes of regulation to be achieved at least cost. Hence, such a regulatory model should not be used in Victoria if the outcome can be clearly specified, and there are multiple solutions to mitigate the regulatory problem. 6 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation The Victorian Government encourages that – where appropriate and where permitted by the enabling legislation – prescriptive rules should be avoided, and consideration should instead be given to the use of: performance-based standards (or principle-based regulation in cases where it is not feasible to set objective performance based-standards); process-based regulation, where there are substantial risks that need to be managed simultaneously; and/or targeted regulatory requirements proportionate to risk. Performance-based standards specify desired outcomes or objectives, but not the means by which these outcomes/objectives have to be met. Taking the above example of reducing workers’ exposure to noise levels, a performance-based approach would be to set a required outcome for each firm in terms of the maximum decibels to which workers should be exposed. It would then be left to each firm in the industry to decide how it would achieve this outcome. This allows for different technological solutions to the regulatory problem, and should be the preferred method of regulation when the regulatory standard can be clearly expressed and measured and there are different potential compliance methods. In some cases, it will not be feasible to set objective performance-based standards, either because any reasonable performance benchmark would depend on the particular circumstances, or because objective standards would need to change over time as knowledge develops on how to address individual risks. However, these issues also make prescriptive regulation unsuitable. Principle-based regulation addresses these issues by requiring the application of general objectives or principles, rather than specific outcomes. An example of principle-based regulation is the general duty under occupational health and safety legislation of eliminating or reducing risks so far as is ‘reasonably practicable’. Process-based regulation is increasingly adopted when governments are seeking to manage substantial but diverse risks. It is generally best applied when: there are a number of substantial risks that need to be managed simultaneously; there are a range of management measures available; and individual firms within the regulated industry have sufficient capacity to effectively assess risks and develop tailored solutions to mitigate those risks under their control. However, this regulatory model should not be used when there are few risks, and/or the options for risk management are well known. Examples include requirements to prepare and implement: risk management plans for cooling towers; safety management systems for major hazard facilities under occupational health and safety legislation; risk management plans for water suppliers regarding the quality of drinking water; emergency management plans for public passenger vehicles such as buses; and management plans for electrical distribution and transmission companies regarding electrical line clearance. Process-based regulation requires certain processes to manage the risk of adverse outcomes, and is generally centred on the key elements of: Risk identification – this involves identifying all hazards (i.e. anything that has the potential to cause harm). Risk assessment – this involves making a judgement about the seriousness of each hazard, and deciding which hazard requires the most urgent attention. An assessment must be made on the likelihood of adverse outcomes, and the impact of such outcomes. Risk controls – this involves identifying ways to eliminate each risk and, where this is not appropriate, how it might be controlled to reduce the impact of adverse outcomes and the likelihood of them occurring. The judgement on the required controls will often be guided by more general principles that underpin the regulatory framework, such as ‘as far as reasonably practicable’. Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 7 The risk management process is generally required to be documented to demonstrate compliance, and often a risk management plan must be submitted to government or made available for inspection. Regulations may require regular audits of the implementation of the plan, and reviews at specified intervals or after specified events. The main advantages that performance-based standards and process-based regulation have over prescriptive regulation are the greater flexibility afforded to regulated parties in achieving the desired outcomes (which can also encourage the pursuit of low cost solutions), and their ability to be used in situations where circumstances may change over time (e.g. as knowledge improves and/or technology advances). Nevertheless, they do have some disadvantages. For example, the greater flexibility (and freedom) offered by performance-based regulations is often cited as a problem for those being regulated as it can lead to uncertainty as to whether the actions they undertake are sufficient to satisfy the standards set by the regulations. Where regulated parties (for example, small businesses) lack the resources to tailor compliance approaches, guidance material that demonstrates (without prescribing) how to comply can be effective in reducing compliance costs. Targeted regulatory requirements according to risk set out: different risk classes or categories of regulated entity according to the activities they undertake; and regulatory obligations for each category. In this way, the regulatory obligations placed on an entity are able to be more proportionately matched to the risk the activities impose. Entities classified as high risk can in this way be regulated much more stringently (for example in terms of licensing criteria, performance standards and monitoring arrangements) than low risk entities (which might not be required to be licensed and have less onerous reporting requirements). An example of such a risk-based regulatory approach is the classification of food businesses under the Food Act 1984. Under this regime, businesses and groups that sell food are classified into one of three classes, according to the public health risks involved in handling foods: Entities preparing temperature-controlled meals eaten on-site by vulnerable people (e.g. nursing homes) fall into the highest risk class. Regulatory requirements for this class include a requirement to have an independent food safety program and a food safety supervisor, and undergo two annual compliance checks. Businesses in the lower risk class (e.g. convenience stores that only handle packaged food that is refrigerated or reheated) are not required to have a food safety program or food safety supervisor. Instead, they must complete simple record keeping and undergo one annual compliance check. Very low risk businesses (e.g. chemists selling packaged food that does not require temperature control) are subject to the lowest level of regulation. They do not have to keep any records and do not need to undergo an annual compliance check. A pre-condition for such an approach towards targeting of regulatory requirements across a sector is having a whole of sector risk assessment framework and appropriate data to enable regulated parties to be assessed (or to self-assess) and be categorised into appropriate classes. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages of the various approaches to regulation is provided in Table 2. 8 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Table 2: Approaches to regulation – summary of advantages and disadvantages Advantages Prescriptive rules Disadvantages Certainty and clarity – requirements Inflexibility in meeting regulatory are set out in detail; standardised solutions; ease of enforcement The decision to prosecute can be made on objective criteria Performance-based Suitable for industries subject to changing circumstances (e.g. due to standards technological change) Greater flexibility in dealing with technical matters Encourages least-cost means of achieving the outcome Lower compliance costs May encourage continual improvement through innovations Process-based regulation Suitable for controlling substantial Targeted regulatory requirements objectives High administration and compliance costs Unsuitable in industries subject to changing circumstances (e.g. due to technological change), where prescriptive rules may be rendered obsolete May lead to uncertainty as to whether actions undertaken satisfy standards set by regulation Generate uncertainty because circumstances giving rise to prosecutions may be determined subjectively May require high levels of guidance Increased risk of non-compliance because standards may not be uniform across the industry May be costly to administer (particularly for small firms) There is a risk of regulatory creep where scope of risks covered or standards of controls required increase over time Potential for overlap with other general regulation but diverse risks Can be applied to complex areas of different operations subject to technological change May promote innovation in the development of risk mitigation practices May encourage greater ownership and accountability for risk mitigation practices Suitable where regulated entities or May only be feasible where there is activities pose varying risks a detailed understanding of the risk Enables proportionate targeting of profile and ability to differentiate regulatory requirements (and risk across regulated activities focussing of enforcement activity) on the basis of risk Effective in ensuring that regulatory burden faced by regulated entities is not disproportionate/excessive Regulation can also be viewed along a ‘continuum’, with explicit government regulation representing one end of this continuum, and self-regulation at the other extreme (see Figure 2). Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 9 Figure 2: Regulation continuum Self-regulation Voluntary agreement within an industry Characterised by voluntary codes of conduct or standards No government enforcement Quasi-regulation Government influences business to comply Government assists with the development of codes of conduct, accreditation and/or rating schemes Ongoing dialogue between government and industry No government enforcement Co-regulation Strong partnership between industry and government Industry develops own code of conduct or accreditation/ratings schemes with legislative backing from government Explicit government regulation (legislation) Industry’s role in formulating legislation is limited to consultation, where relevant Compliance is mandatory, with punitive sanctions for non-compliance Little flexibility in interpretation and compliance requirements Government enforcement 10 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Self-regulation Self-regulation (or voluntary codes of practice or standards) refers to the benchmark actions or procedures, as determined by the particular industry or profession, that are generally acceptable within the peer group and the wider society. The relevant industry is solely responsible for enforcement, although government may also be involved in a limited way – for example, through the provision of advisory information. Self-regulation usually implies that firms in an industry or members of a profession have accepted mutual obligations. These obligations are often described in a code of practice or conduct. Advantages Disadvantages Because of agreement between major industry No legal remedies exist for breaches of the participants and therefore high levels of awareness, compliance may be high Utilises the expertise and experience of those in the industry Allows for innovative behaviour of industry participants Lowers administrative costs for governments Can facilitate national and/or international consistency of requirements code or agreement Could be used to promote anti-competitive behaviour (e.g. rules may confer commercial advantage) Imposes monitoring costs that are incurred by the industry or professional association Compliance may be low if a sense of commonality amongst those affected is not present May implicitly create barriers to entry and trade Suitable conditions for use The problem to be addressed is a low-risk event, or of low impact The problem can be fixed by the market When there is sufficient power and commonality of interest within an industry to deter non-compliance When the cost of compliance is small Where a body with appropriate expertise and representation is available to develop an industry code or standard Quasi-regulation and co-regulation Quasi-regulation and co-regulation are similar in that they refer to situations where the regulatory role is shared between government and industry. In the case of quasi-regulation, there is no formal enforcement role for the government, but the government does influence businesses to comply by assisting in the development and/or endorsing industry codes of conduct. An example is the Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) Code of Conduct, which was endorsed by Commonwealth and state/territory governments, and which applies to financial transactions that are effected through the use of a card and a personal identification number. The code is monitored by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, and requires EFT providers to issue customers with certain information and a transaction receipt. Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 11 Co-regulation typically refers to a situation where an industry or professional body develops a code of practice (or accreditation or rating scheme) in consultation with the government, and the government provides legislative backing to the code/schemes (and consequently plays an enforcement role). Co-regulation has long been adopted in professions such as lawyers and engineers. Advantages Disadvantages Utilises expertise of industry or professional Could raise barriers to entry within an industry associations (e.g. through standards or education Encourages industry or professional requirements) association to take greater responsibility for Unintended monopoly power gained by the behaviour of its members market participants could restrict competition Reduces requirements for government Danger of regulatory ‘capture’, whereby resources to be dedicated to regulation government agencies promote the interests of Industry involvement is likely to improve regulated parties at the expense of the industry acceptance of the scheme and ensure community at large that the requirements are practical to the characteristics of the industry Suitable conditions for use There is public interest in some government involvement in regulatory arrangements, and the issue unlikely to be addressed by self-regulation Where professional independence is a major consideration When there are advantages in the government engaging in a collaborative approach with industry, with industry having strong ownership of the scheme, which will require: – a specific industry solution rather than regulation of general application; – a cohesive industry, where incentives and interests are aligned; and – a strong industry association with broad coverage. Explicit government regulation Sometimes referred to as ‘black letter law’, explicit government regulation covers the making of legislation, either primary or subordinate, to achieve specified objectives. It attempts to change behaviour by detailing how regulated parties should act, and it generally imposes punitive sanctions (such as fines or even custodial sentences) when there is non-compliance with the regulation. Advantages Disadvantages Creates certainty Greater industry-wide coverage Enforcement via legal sanctions likely to lead May impose significant burden on affected to higher levels of compliance parties (e.g. high compliance costs) Significant resources may be required to establish and maintain regulatory framework Can be more inflexible than other forms of intervention Suitable conditions for use The problem to be addressed is high risk, with high impact/significance (e.g. public health and safety) The government requires the certainty imposed by legal sanctions Universal application is required (e.g. coverage of one or more industry sector) There is a systematic compliance problem that requires effective sanctions 12 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Increased enforcement of existing provisions The possibility of increasing enforcement of existing provisions should be considered when there is relatively low levels of compliance, perhaps among particular groups. This option may simply require an upgrade of existing enforcement mechanisms, and is particularly relevant for long-standing mechanisms given that technology could have changed, allowing enforcement mechanisms to be reconsidered or re-engineered. A good example of this is the development of laser-based detection devices to enforce traffic speeding laws. Advantages Disadvantages Increases the effectiveness of regulation Not all problems can be solved by simply without increasing its complexity increasing enforcement mechanisms Appropriate response to allow for the May require unacceptably high costs, without adoption of new technology for enforcement delivering benefits mechanisms May increase the need for additional Demonstrates a credible threat – i.e. penalties resources to administer increased for non-compliance are imposed, which prosecutions prevents the law from being brought into disrepute Suitable conditions for use When technology changes rapidly When too many breaches are occurring When it is cost-effective to do so When costs of non-compliance are great Extending the coverage of existing legislation If essential facilities or procedures are already provided by an existing legislative regime, it may be more efficient to extend the application of that legislation to related concerns, rather than have them duplicated. For example, if enforcement mechanisms (e.g. inspections, reporting requirements) already exist for manufacturers or suppliers of certain types of drugs or poisons, these might be efficiently and effectively applied to manufacturers or suppliers of alternative medicines. This approach is also likely to assist in ensuring the consistency of government action in the treatment of issues with similar concerns. Advantages Disadvantages Eliminates unnecessary duplication of a Not appropriate for problems that require proven legislative framework Enables better utilisation of existing legislative framework Promotes consistent treatment of related issues or concerns Saves resources and costs associated with developing an alternative or parallel framework May promote a high level of compliance where existing legislation is well understood specific regulation to address the particular circumstances of the case Could result in legislation that is too complex Current resources may not be able to deal adequately with all matters covered by the legislation Not as flexible as other options when technology is changing rapidly Suitable conditions for use When existing laws are pertinent to the issue being addressed When existing legislation is comprehensive and well understood When extending existing legislation can be achieved with minimum cost or difficulty Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 13 Targeted regulatory requirements according to risk Traditional command-and-control approaches to regulation do not acknowledge or reward compliance with regulations. Accordingly, industries with good track records are penalised for non-compliance on the same basis as firms that frequently breach the law. Hence, in order to capture offenders, regulations sometimes place monitoring and reporting requirements on complying industry participants that are too onerous. As a consequence, consideration should be given to risk-based approaches that are less burdensome for low risk and/or highly compliant parties, while focusing compliance and enforcement activity on high risk and/or low compliance parties. Under such an approach, organisations that show a consistent record of compliance with the regulations could be rewarded. (Such rewards could include a reduction in the number of licences required, a lowering of the frequency of inspections or audits, reducing reporting requirements, or by the allowance of self-regulation). Those undertaking higher risk activities or with a history of non-compliance on the other hand, would face stricter regulatory requirements and more frequent inspections. Advantages Disadvantages Provides economic incentives that encourage Dependent on data for regulator to assess risk compliance Allows regulator efforts to be focused in areas where community benefits are greatest Can provide incentives for regulated parties to improve their performance profile of regulated parties Suitable conditions for use When such economic incentives are likely to increase the incidence of good behaviour Negative licensing Negative licensing is designed to ensure that participants that have demonstrated previously that they are incompetent or irresponsible are precluded from operating in a particular industry. As a result, the worst offenders against the set standards are removed from the industry/profession without, at the same time, placing an undue burden of registration on the entire industry/profession. Advantages Disadvantages Avoids the need of administrative or personal As no screening occurs, the number of certification. The resulting lower costs on participants may result in lower prices for consumers Costs of entry are lower compared with the situation where certification is required inappropriate participants initially entering an industry may be higher than under a registration process Some participants may be able to operate undetected or act inappropriately before they are detected – i.e. licence removal will only occur after the detection of a breach The process relies on objective evidence that may not be a reliable indicator of future inappropriate behaviour Enforcement activities may need to be increased, thereby increasing monitoring costs Suitable conditions for use When monitoring requirements are low When screening processes are already carried out by some organisation or law enforcement body 14 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Public information and education campaigns Research on regulatory compliance and the practical experience of regulators indicates that non-compliance with the requirements of regulations can be the result of ignorance rather than any intentional desire to flout the law. Where the problem to be addressed results from a lack of knowledge amongst consumers or participants in an industry, then an education program should be considered. An education campaign by government and/or industry bodies is likely to be successful where the target can be easily identified and reached economically. Approaches include advertising in industry magazines and newspapers, distributing information brochures in areas where the problem exists, soliciting community groups or associations to disseminate information, or targeted mail-outs to affected groups. Advantages Disadvantages Represents a quick method of disseminating May be less effective than other regulatory information about compliance requirements approaches as it relies on voluntary May reduce costs to the government and the compliance rather than being supplemented community because of a higher level of by the element of coercion awareness about issues of concern The community can become de-sensitised or May reduce resources expended on weary of messages, thereby reducing the implementing regulatory programs and effectiveness of education campaigns, ongoing enforcement particularly if the problem is long-term Can educate the community about the virtues Target groups may not be easily identified of a particular policy and therefore increase Public interest may warrant further action compliance than just education, particularly when the issue being regulated is of a serious nature Suitable conditions for use When the problem or non-compliance results from misinformation or a lack of information When target audiences can be easily and economically reached When the virtues of a particular policy are not well understood When a light-handed approach would be more appropriate Information disclosure While closely related to public education campaigns, this option requires information about the attributes of products or processes to be disclosed (e.g. hazardous substances in use, food labelling, disclosure statements for buying a franchise and entering into a retail lease). Information disclosure does not directly seek to prohibit or regulate the consumption of a good or service, but is designed to ensure that the public is aware of all the advantages and disadvantages of using the products. Advantages Disadvantages Influences user behaviour without prohibiting The information necessary could be too it Facilitates informed decision-making by consumers Promotes high-quality goods, services and quality Preserves the opportunity for innovation technical (e.g. information on contents of drugs) May not be perceived as being responsive enough Suitable conditions for use When consumers do not possess full information When ignorance or lack of understanding is an element of non-compliance Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 15 Market-based instruments Market-based instruments are policy interventions that use the characteristics of well-functioning markets to deliver policy outcomes. If properly designed, they can reveal important information to policy makers and provide incentives which align individual and public objectives, helping government to achieve its objectives while avoiding the regulatory burden of more traditional regulatory intervention. Market-based instruments can be applied when naturally occurring markets are missing or inefficient, and may be effective when individuals each have different costs and benefits associated with conforming to a policy’s requirements. Taxes and subsidies Although taxes require legislation and are primarily a source of revenue for governments, they can also be used to influence the economic and social behaviour of individuals and firms. By increasing the cost of an action to individuals or firms (i.e. internalising the costs of any externality), a reduction in undesirable behaviour can be achieved. When the explicit aim of imposing a tax is to change behaviour/internalise an externality, particular consideration needs to be given to the underlying problem to be addressed and the extent to which it is reasonable to expect behaviour to respond to a change in price. Where governments wish to encourage certain behaviours, subsidies could be provided – for example, grants to home owners for installing insulation, or cash-back payments for purchases of energy efficiency appliances such as washing machines. Advantages Disadvantages Provide greater flexibility and freedom of May be difficult to target the policy directly – choice for industry participants in terms of the i.e. determine the required amount of the methods of compliance instrument to get the desired response Encourage economically efficient allocation of Need to take into account political resources considerations and commitments (e.g. in Encourage least-cost technologies and terms of overall levels of taxation) methods of compliance Low enforcement costs Avoid problems associated with centralised discretionary decision-making Suitable conditions for use When the behaviour to be addressed is across many sectors or areas of the community When the activities being regulated are financially based Tradeable permits Tradeable permits are government-issued licences that grant a tradeable property right to the holder – i.e. they grant the holder the right of use of a material or resource, or the right to engage in a particular activity that can be bought or sold. These permits can encourage an efficient allocation of resources and a market-based solution to environmental and distributive concerns. Tradeable permits can force firms to internalise (pay for) the external costs that their activities place on society. Such permits may be used to control pollution, and there has been much discussion about the use of tradeable permits in controlling the emission of greenhouse gases. 16 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Generally, governments will make available a fixed supply of permits or licences, which would be consistent with a desired level of output. However, there is a risk that tradeable permits may increase the level of market power of incumbent firms or individuals. Advantages Disadvantages Efficient mechanism to require firms and Can represent a barrier to entry individuals to internalise their external costs Can limit the number of participants in an Encourage adoption of least-cost technologies industry and therefore reduce competition Provide financial incentives for firms to engage Excessive rents (monopoly profits) may accrue in desirable behaviour, thereby protecting the to participants environment and/or resource Suitable conditions for use When the market and market participants can be easily identified When rights involved can be legally specified When the method for trade or exchange can be adequately defined When transaction costs (i.e. those associated with the trade of permits) are low When a competitive market can be sustained, thus limiting market power of incumbents When monitoring of usage is feasible When the desired level of output is measurable and that measurement is cost-effective Procurement For certain types of issues, for instance when goods and services are not provided by private markets in sufficient quantity, Governments can achieve specific objectives by procuring those goods and services directly. If designed effectively, this can lower compliance costs on individuals, and lower monitoring and enforcement costs for government. For instance, mechanisms such as auctions can be used to reveal low-cost service providers, while incentive structures can be embedded in service contracts to ensure that individuals and firms behave as government requires. Programs such as Bushtender and ecoTender are examples of where the Victorian Government has procured a public good (in this case, environmental outcomes) instead of compelling individuals to deliver its objectives through regulation. Advantages Disadvantages Can identify low cost providers of government Can levy the costs of achieving policy objectives objectives on government Can target monitoring and enforcement effort, lowering administrative costs Suitable conditions for use When individuals and firms have different costs and benefits associated with contributing towards government objectives and these are unknown to policy makers When the outcomes of individual actions are easily measurable Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 17 Attachment 1. Maintaining Consistency with the Australian Consumer Law Background The Australian Consumer Law (ACL) is a single, national law that is applied consistently across all Australian jurisdictions, including at the Commonwealth level. The ACL includes: core consumer protection provisions prohibiting misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce, and declaring unfair terms in standard form consumer contracts to be void; specific protections against defined ‘unfair’ practices, including enumerated instances of misleading or false conduct, pyramid selling, unsolicited supplies of goods and services, component pricing and incorrect billing and receipting practices; and regulation of certain aspects of consumer transactions, such as: o statutory consumer guarantees for consumer goods and services, including business goods valued under $40,000; o a national legal framework for unsolicited consumer agreements, including doorto-door and telephone sales; o a national product safety law for consumer goods and product-related services; and o provisions for enforcement powers, penalties and consumer redress. Where provisions in State/Territory legislation duplicate or are inconsistent with the ACL, there is a risk of unnecessary regulation and/or confusion. The Commonwealth, State and Territory governments have agreed to a principles-based approach to maintaining ACL consistency through the 2009 Intergovernmental Agreement for the Australian Consumer Law (the IGA). Inconsistent provisions are those which alter the effect of the ACL by conflicting with a command, power or other provision in the ACL, or which alter, impair or detract from the operation of the ACL. Examples of inconsistent provisions are where: the proposed/existing law cannot be followed concurrently with the ACL; the ACL permits a certain activity that is prohibited by the proposed/existing law; and the ACL confers a right to protection which the proposed/existing law seeks to remove. Duplicative provisions are those that replicate the equivalent ACL-provision (with no divergence), or which are perhaps framed in a different way, or only concern certain industries but provide identical obligations and/or protections to the ACL. These are not inconsistent per se but can cause confusion among suppliers and consumers. Such laws can also become inconsistent over time if amendments to the ACL or the law in question are passed at different times. Complementary provisions are those that generally align with the ACL but have some elements that go over and above what the ACL provides for, such as specific examples of prohibited conduct (i.e. misleading or deceptive labelling of food). 18 Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation Victoria’s approach to maintaining IGA consistency Consistent with the IGA, Victoria’s approach to maintaining IGA consistency is as follows: for new legislative/regulatory provisions, consideration should be given to whether the issues being addressed are covered by the ACL and, if so, whether additional industry specific provisions are necessary in light of the ACL provisions; and where existing legislation/regulation is being reviewed or amended, consideration should be given to whether existing provisions are inconsistent with, complementary to, or duplicative of the ACL and, if so, whether those provisions are necessary to provide more effective and/or certain consumer protection. There is no onus to justify retaining existing consumer protection provisions within Victorian statutes. In some cases, these may have particular context in relation to the industry or activity to which they apply, complementing the ACL laws. For guidance on the Australian Consumer Law, departments may wish to contact CAV’s Policy and Legislation Branch on Ph: 8684 6484. The reporting arrangements for departments are to assess new proposals and existing provisions using the template available at http://www.consumerlaw.gov.au/content/Content.aspx?doc=consistency_with_acl.htm and forward it to the CAF Secretariat. Victorian Guide to Regulation Updated July 2014, Toolkit 1: Purposes and types of regulation 19 dtf.vic.gov.au