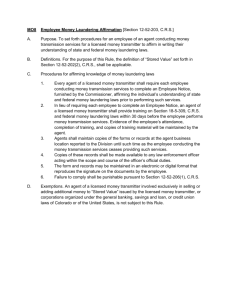

Chapter 4 - Tools and Resources for Anti

advertisement