learning - Warren County Schools

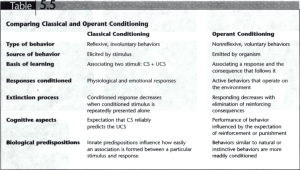

advertisement

LEARNING Chapter 6 (Bernstein), pages 194-229 What is LEARNING? LEARNING is the adaptive process through which experience modifies preexisting behavior and understanding; relatively permanent change in behavior based on prior experiences plays central role in development of most aspects of human behavior humans and animals learn primarily by: 1. experiencing events 2. observing relationships between those events 3. noting consistencies in the world around them 3 guiding questions of psychological research on learning: 1. Which events and relationships do people learn about? 2. What circumstances determine whether and how people learn? 3. Is learning a slow process requiring lots of practice OR does it involve sudden flashes of insight? LEARNING ABOUT STIMULI HABITUATION and SENSITIZATION People appear to be genetically tuned to attend to and orient toward certain kinds of events. These novel stimuli attract attention. loud sounds special tastes bright lights pain Learning that involves exposure to a single stimulus is referred to as non-associative learning. Two simple forms of non-associative learning: habituation and sensitization Unchanging stimuli decrease our responsiveness, and we adapt to such stimuli (habituation) After a response to a stimulus is habituated, dishabituation, or reappearance of the original response, occurs if the stimulus changes. Sensitization is an increase in responsiveness to a stimulus. (e.g.,people & animals show exaggerated responses to unexpected, potentially threatening sights or sounds, especially when aroused.) LEARNING ABOUT STIMULI Richard Solomon’s OPPONENT PROCESS THEORY New stimulus events, esp. those arousing strong emotions, disrupt a person’s equilibrium. This disruption triggers an opposite (opponent) response (process) that eventually restores equilibrium. If the event occurs repeatedly, the opponent process becomes stronger and eventually suppresses the initial reaction to the stimulus, creating habituation. e.g., development of drug tolerance and addiction e.g., engagement in high risk/arousal activities such as skydiving e.g., accidental drug overdoses NOTE: Opponent process explanations based on habituation and sensitization cannot explain many of the behaviors and mental processes that are the focus of psychology. Learned associations between certain environmental stimuli and certain opponent responses affect our thoughts and behaviors as well. CLASSICAL CONDITIONING is one type of associative learning that builds associations between various stimuli as well as between stimuli and responses CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations Pavlov’s Discovery Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov’s classic experiment taught a dog to salivate to a musical tone. First, Pavlov confirmed a dog salivates when meat is put on its tongue (reflex) but not when a tone sounds (neutral stimulus). reflex a swift, unlearned automatic response to a stimulus neutral stimulus a stimulus that initially does not trigger the reflex being studied second, he repeatedly paired the tone and the meat; each time he sounded the bell, he put a bit of meat powder in the dog’s mouth (the tone predicted that meat powder was coming). eventually, the dog salivated to the tone alone...even if no meat powder was given. Pavlov’s experiment showed a form of associative learning call CLASSICAL CONDITIONING. CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations CLASSICAL CONDITIONING a form of associative learning in which a neutral stimulus is repeatedly paired with a stimulus that already triggers a reflexive response until the neutral stimulus alone triggers a similar response unconditioned stimulus (UCS) the stimulus that already elicits a response without learning unconditioned response (UCR) the automatic response to the UCS conditioned stimulus (CS) the neutral stimulus that is repeatedly paired with the unconditioned stimulus conditioned response (CR) the reaction resulting from the pairing of the UCS and the CS in which the CS alone elicits a learned or “conditioned” response CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations CONDITIONED RESPONSES OVER TIME EXTINCTION the CS occurs without UCS and the association gradually weakens until the CR disappears; the association is not erased, just suppressed RECONDITIONING the relearning of the CR after extinction; requires fewer pairings of the CS with the UCS than the original learning (because extinction does not erase the association) SPONTANEOUS RECOVERY the sudden reappearance of the CR after extinction but without further CS-UCS pairings In general, the longer the time between extinction and the representation of the CS, the stronger the recovered conditioned response was in the first place. e.g., when a person hears a song or smells a scent associated with a long-lost lover and experiences a ripple of emotion (the conditioned response) CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations STIMULUS GENERALIZATION & DISCRIMINATION STIMULUS GENERALIZATION when stimuli that resemble the CS and trigger a CR The greater the similarity between a new stimulus and the conditioned stimulus, the stronger the conditioned response e.g., ____________________ STIMULUS DISCRIMINATION when people and animals learn to differentiate among similar stimuli This complements generalization by preventing people (and animals) from being completely disrupted by overgeneralization. e.g., ____________________ CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations THE SIGNALING OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS Classical conditioning depends on one event reliably predicting or signaling the appearance of another. This leads to the development of mental representations of the relationships between important events in the environment and expectancies about when such events will occur. FACTORS DETERMINING WHETHER AND HOW A CONDITIONED RESPONSE IS LEARNED 1. TIMING 2. PREDICTABILITY 3. SIGNAL STRENGTH 4. ATTENTION 5. BIOPREPAREDNESS 6. SECOND-ORDER CONDITIONING CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations FACTORS DETERMINING WHETHER AND HOW A CONDITIONED RESPONSE IS LEARNED 1. TIMING The timing of the CS relative to the UCS affects the speed of conditioning. FORWARD CONDITIONING the CS precedes and thus signals the UCS; works best when there is an interval between the CS and the UCS (from a fraction of a second to a few seconds to more than a minute depending on the particular CS, UCS, and UCR involved) BACKWARD CONDITIONING the CS follows the UCS; classical conditioning works most slowly this way (if it even works at all) 2. PREDICTABILITY not enough for the CS and the USC to just occur together; they must reliably occur together before classical cond. occurs; cond. is quicker when the CS always signals the UCS and only the UCS. (e.g., Moxie and Fang’s growling and biting) 3. SIGNAL STRENGTH CR learned faster when UCS is strong rather than weak; speed with which a CR is learned also depends on the strength of the CS (e.g., intense shock, louder tone) 4. ATTENTION The stimulus most closely attended to, most fully perceived at the moment, dominates the others in later triggering a CR (e.g., getting stung by a wasp at the beach after putting on sunscreen while sipping lemonade, reading a magazine, and listening to Beyonce’) CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations FACTORS DETERMINING WHETHER AND HOW A CONDITIONED RESPONSE IS LEARNED 5. aversions...see BIOPREPAREDNESS It to was once believed thatseems any CS had an equal chance of being associated any UCS, but this equipotential toassociations. be incorrect. Some stimuli are more easilywith associated with each other, perhaps because organisms are “genetically tuned” or “biologically prepared” develop certain conditioned (e.g., taste below) A) A taste paired with nausea will lead to an aversion to the taste. A light and/or sound paired with nausea produces no aversion and no learning. WHY? Something eaten is more likely to naturally cause nausea than an audio-visual stimulus. B) A taste paired with electric shock will not produce an aversion (learning) to the taste. But an audio-visual stimulus, such as lights and bells, paired with an electric shock produces aversion (learning) to pain. WHY? In real life, organisms should be “tuned” to associate pain from a shock with external stimuli such as sights or sounds rather than with something eaten. In sum, animals (including humans) are prone to learn the type of associations that are most common or relevant to their environment. CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations FACTORS DETERMINING WHETHER AND HOW A CONDITIONED RESPONSE IS LEARNED 6. SECOND-ORDER CONDITIONING This occurs when a CS is paired with a new stimulus until the new stimulus makes the CS act like a UCS. This creates conditioned stimuli out of events associated with it. (e.g., a child who has experienced a painful medical procedure at the doctor’s office) • UCS the painful medical procedure • CS the doctor’s white coat (the coat signals pain to follow...the UCS) • CR conditioned fear of the doctor’s office because of the pain associated with it • If the child later sees a white-coated pharmacist at the drugstore, then... • UCS becomes the white coat • CS drugstore (the once-neutral store signals the appearance of the white coat) • CR second-order conditioned fear of white coat due to pain associated with it CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations In Review... CLASSICAL CONDITIONING: Learning Signals and Associations APPLICATIONS OF CLASSICAL CONDITIONING 1. PHOBIAS extreme fears of objects/situations that dont reasonably warrant such intense fears SYSTEMATIC DESENSITIZATION the association of a new response (relaxation) with a feared stimulus; the CR (relaxation) replaces the old CR (fear). 2. PREDATOR CONTROL Western ranchers lacesheep muttonanwith lithium chloride they eat it; this makes undesirable food. which makes wolves and coyotes ill after 3. DETECTING EXPLOSIVES Researchers are attempting to pair attractive scents with the smell of drugs or chemicals used to teach insects (such as wasps) to detect concealed explosives or drugs.in explosives 4. PREDICTING ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE A puffconditioning of air in the eye at paired with a flash of light willAlzheimer’s result in a blink in response to the lightis alone through classical conditioning. Elderly people who show an impairment in the eye blink are greater risk for developing because the hippocampus involved both with the eye blink conditioning and Alzheimer’s disease. OPERANT CONDITIONING: Learning the Consequences of Behavior OPERANT CONDITIONING the process through which an organism learns to respond to the environment in a way that produces positive consequences and avoids negative ones. Edward Thorndike’s PUZZLE BOX using a cat in a box with several strings and levers, Thorndike devised a “puzzle box” in which the animal had to perform tasks ranging from simple to complex to escape from the box and receive a reward. The cat had to correctly figure out what behaviors would allow it to get out of the box and receive the food on the other side. Thorndike believed the behaviors that didn’t result in escape and reward would be stamped out (weakened) and those that DID have a positive result would be stamped in (strengthened) and remembered forever and utilized in future similar situations. This is the basis of the theory known as the law of effect which states behaviors resulting in rewards are strengthened while behaviors that do no result in rewards are weakened. Thorndike described this kind of learning as instrumental conditioning because responses are strengthened when they are instrumental (essential or influential) in producing rewards. A Puzzle Box OPERANT CONDITIONING: Learning the Consequences of Behavior OPERANT CONDITIONING the process through which an organism learns to respond to the environment in a way that produces positive consequences and avoids negative ones. B. F. Skinner’s SKINNER BOX (and another one from the Psych files) Skinner expounded upon Thorndike’s theory by emphasizing that an organism learns a response by trying actions that operate on the environment (operant conditioning) An operant is a response or a behavior that affects the world; it is a response that “operates” on the environment. Skinner devised the “Skinner box” to analyze how behavior is changed by its consequences. In the Skinner box, learning was measured in terms of whether an animal successfully completed a trial (got out of the box). The Skinner box measured learning in terms of how often an animal responded during a specified period of time. A Skinner Box OPERANT CONDITIONING: Learning the Consequences of Behavior According to Skinner, how a subject interacts with it’s environment is based primarily on the reinforcement or punishment the subject received. PUNISHMENT a stimulus that, when made contingent on a behavior, decreases the strength of the exhibited behavior acts as a deterrent to behavior e.g., ______________________________ REINFORCER a stimulus that, when made contingent on a behavior, increases the strength of the exhibited behavior, increases the strength of the exhibited behavior necessary for the continuation of a behavior primary reinforcers any reinforcing stimuli that satisfies a biological need (food, water, sex, warmth, etc.) secondary (conditioned) reinforcers any previously neutral stimuli that have gained reinforcement value after being associated with another reinforcer (grades, money, praise, etc.) OPERANT CONDITIONING: Learning the Consequences of Behavior Skinner believed ALL behavior could be explained in one of four ways: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. “Skinner Squares” Appetitive (Desirable Stimulus) Positive Reinforcement presenting a liked stimulus, behavior INCREASES EXAMPLES: money for good grades pay raise for good job performance praise and recognition for good behaviors Negative Punishment (Omission) removing a liked stimulus, behavior DECREASES EXAMPLES: grounded for breaking curfew “timeout” for bad behavior The Big Bang Theory Aversive (Undesirable Stimulus) Positive Punishment presenting a disliked stimulus, behavior DECREASES EXAMPLES: spanking for misbehavior washing mouth out with soap for using foul language scolding and criticism for poor behaviors Negative Reinforcement removing a disliked stimulus, behavior INCREASES EXAMPLES: fewer chores for doing well on a test early parole for good behavior in prison OPERANT CONDITIONING: Escape and Avoidance Conditioning ESCAPE CONDITIONING occurs as an organism learns to respond to stop an aversive stimulus. e.g., To “terminate” intense cold, person may turn up the heat in his home. e.g., ______________________________ AVOIDANCE CONDITIONING occurs when an organism responds to a signal in a way that avoids exposure to an aversive stimulus that has not yet arrived. e.g., To avoid the intense cold of winter, a person may fly to a warmer environment when the leaves have fallen from the trees but before it turns cold. e.g., ______________________________ Avoidance conditioning is one of the most important influences on everyday behavior. Why? ______________________________ Avoidance is a very difficult habit to break, partly because avoidance responses are often reinforced by fear reduction. Avoidance also prevents learning of alternative behaviors. e.g., People who avoid escalators never find out they are safe. e.g., ______________________________ OPERANT CONDITIONING: Discriminative Stimuli and Stimuli Control STIMULUS DISCRIMINATION occurs when an organism learns to make a particular response in the presence of one stimulus but not another. When this occurs, the response is under stimulus control. e.g., Although you are repeatedly rewarded for telling jokes during lunch, you are not likely to do so at a funeral. e.g., ______________________________ STIMULUS GENERALIZATION occurs in operant conditioning when organisms perform a response in the presence of a stimulus that is similar (but not identical) to the one that previously signaled the availability of reinforcement. e.g., You might hold the door open for different people (of different ages, gender, ethnicity) as you enter the building the same time they do. e.g., ______________________________ Stimulus discrimination and stimulus generalization work together in operant conditioning. We sometimes differentiate our behaviors based on the particular circumstance (discrimination), but we also categorize some behaviors because the rewards for those behaviors are similar (generalization). OPERANT CONDITIONING: Forming Operant Behavior SHAPING Forming operant behavior may require multiple trials during which SHAPING is important. SHAPING involves creating a new behavior based on a sequence of rewarding behaviors that come closer and closer to the ultimate behavioral goal (successive approximations) e.g., teaching a child to make his bed competently 1. reward for pulling up covers 2. then reward for pulling up covers smoothly 3. then reward for pulling up covers and bedspread 4. finally reward for pulling up covers and bedspread without wrinkles OPERANT CONDITIONING: Forming Operant Behavior SECONDARY REINFORCEMENT PRIMARY REINFORCERS (food, water) are innately rewarding. SECONDARY REINFORCERS are rewards people or animals learn to like. A secondary reinforcer (also known as a conditioned reinforcer is a previously neutral stimulus that when paired with a stimulus that is already reinforcing will take on reinforcing properties. Secondary reinforcers can greatly enhance the power of operant conditioning BUT vary in effectiveness from person to person and from culture to culture. e.g., Money alone has no innate value but having it allows a person to buy food and other comfort items. OPERANT CONDITIONING: Forming Operant Behavior DELAY AND SIZE OF REINFORCEMENT The timing of reinforcement is important. In general, the the effect of a reinforcer is stronger when it comes soon after a response occurs. The size of the reinforcement is also important. In general, operant conditioning creates more vigorous, or intense, behavior when the reinforcer is large than when it is small. OPERANT CONDITIONING Strengthening Operant Behavior: Schedules of Reinforcement CONTINUOUS REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE reinforcement occurs after every desired behavior is exhibited pro: necessary for initial learning con: subject comes to expect reinforcement each time; when not provided, the stimulus-response connection may quickly become extinct e.g., rewarding a dog with a treat every time it obeys a command PARTIAL (INTERMITTENT) REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE reinforcement for the desired behavior is given occasionally or periodically elicits a greater number of the desired responses (compared to continuous reinforcement) in the long term because it is unknown when the reinforcement will take place four types of partial reinforcement schedules (see next slide...) OPERANT CONDITIONING: Strengthening Operant Behavior SKINNER INTERVIEW FOUR BASIC TYPES OF PARTIAL (INTERMITTENT) REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE (Note that ratio schedules of reinforcement are based on behaviors performed; interval schedules of reinforcement are based on time elapsed.) 1. Fixed-Ratio (FR) reinforcement provided after a set number of correct responses e.g., factory workers paid $15 for every five pair of gloves produced 2. Variable-Ratio (VR) reinforcement provided after a varying number of correct behaviors e.g., a slot machine at a casino rewarding the player after a varying number of pulls 3. Fixed-Interval (FI) reinforcement provided for the first desired response after a set amount of time has elapsed no matter how many responses have been made during the interval e.g., radio stations telling listeners who just won a prize they are not eligible to win again for thirty days 4. Variable-Interval (VI) reinforcement provided after the first desired response after a varying amount of time has elapsed e.g., father checking son’s room randomly throughout the week to see if his room has been cleaned; if so, the son gets more time on the computer to play video games OPERANT CONDITIONING: Strengthening Operant Behavior Schedules of Reinforcement and Response Patterns Both fixed- and variable-ratio schedules produce very high rates of responding because the frequency of reward depends on the rate of responding. Under a fixed-interval scheduling, the rate of responding typically drops dramatically immediately after the reinforcement and then increases as the time for another reward approaches. A variable-interval schedule typically generates slow but steady responding Schedules and Extinction When a reinforcer no longer follows an operant response, the response will eventually disappear. Partial Reinforcement Extinction Effect Behaviors learned under a partial reinforcement schedule are more difficult to extinguish than those learned through continuous reinforcement due to the uncertainty about reinforcement under the partial schedule. Accidental Reinforcement When a reinforcer happens to follow a behavior by chance, it can function like a partial reinforcement schedule. This may explain learned superstitions. OPERANT CONDITIONING: Why Reinforcers Work Primary reinforcers satisfy basic survival needs (such as hunger and thirst). Premack Principle Each person has a hierarchy of behavioral preferences at any given moment. The higher on the hierarchy an activity is, the greater it’s power as a reinforcer. Preferences differ from person to person and from occasion to occasion. Reinforcers may also work by exerting particular effects within the brain. Olds and Milner found that mild electrical stimulation of certain areas of the hypothalamus activates the “pleasure centers” of the brain. Activation of systems that use the neurotransmitter dopamine is associated with the pleasure of many stimuli (including food, sex, and addictive drugs). OPERANT CONDITIONING: Punishment PUNISHMENT reduces the frequency of an operant behavior by presenting an unpleasant stimulus or removing a pleasant one. This removal is called a penalty. Remember that reinforcement strengthens behavior; punishment weakens it. Drawbacks of Punishment 1. It only suppresses behavior; it does not erase it. 2. It can produce unwanted side effects such as associating the punisher with the punishment. 3. It’s often ineffective unless it is given immediately after the response AND each time the response is made. 4. Physical punishment can become aggressive, even abusive, if administered in anger. 5. Children frequently punished may be more likely to behave aggressively. 6. Punishment conveys information that inappropriate behavior has occurred but does not specify correct alternatives. OPERANT CONDITIONING: Punishment Spanking and Other Forms of Punishment Used by Parents New studies have shown spanking can be effective behavior control technique for children between 3 and 13. Studies show it is NOT detrimental to children’s development IF combined with other disciplinary practices such as: requiring child to pay some penalty for his actions having him provide some sort of restitution to the victims making him aware of what he did that was wrong Guidelines for Effective Punishment 1. Punisher should specify why punishment is being given and that the behavior, not the person, is being punished. 2. Punishment should be immediate and severe enough to eliminate the undesirable behavior. 3. More appropriate behaviors/responses should be identified by the punisher and positively reinforced. OPERANT CONDITIONING: Applications of Operant Conditioning Parents, teachers, coaches, bosses, doctors, and wardens all use Skinner’s principles every day. BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION Behavior modification is simply a change in a previous behavior to a newly desired one. e.g., teacher ignoring inappropriate behavior and rewarding appropriate behavior TOKEN ECONOMY A token economy is an environment that reinforces desirable behavior by rewarding the behavior with secondary reinforcers that can be exchanged for other reinforcers. This form of behavior modification is seen in elementary schools, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals. e.g., A teacher places gold stars next to students’ names on the board when they raise their hands before talking. After a given number of stars have been obtained, the students are rewarded with a new pencil. COGNITIVE PROCESSES IN LEARNING Behaviorists (like Skinner) tried to identify stimuli and responses that build and alter behavior WITHOUT any consideration of conscious mental activity. Cognitive psychologists believe that the mental interpretation or representation of an event is necessary for learning to take place. Cognitivists (and cognitive-behaviorists) argue that both classical conditioning and operant conditioning help organisms detect causality--an understanding of what causes what. This means the conscious mental processes organisms use to understand their environments and to interact with them adaptively are important. How people represent, store, and use information is important in learning. Learning is affected by our expectations and the meaning we attach to events--both conscious mental processes. COGNITIVE PROCESSES IN LEARNING Learned Helplessness Martin Seligman proposed the idea of learned helplessness--failure to continue exerting effort for an outcome because all previous attempts have failed. Operant conditioning teaches organisms they have at least some control over their environment. However, when people (or animals) perceive that their behaviors do not influence outcomes or consequences, they GIVE UP. e.g., A student tries multiple study techniques but continues to fail AP Psychology tests. The student ultimately quits studying because his mental interpretation (or thinking) causes him to feel hopeless and to believe no matter what he does or how hard he tries, he will still fail. personal example: ___________________________________________________________________ COGNITIVE PROCESSES IN LEARNING Latent Learning and Cognitive Mapping Edward Tolman’s experiment with three groups of rats in a maze suggests learning takes place cognitively and is not always immediately observable. Group A: rewarded for learning maze by finding food at the end; gradually improved until they were making only a couple of mistakes in the entire maze Group B: received no rewards and continued to make errors throughout the experiment Group C: received no reinforcement for running the maze for the first ten days and made many mistakes; on the 11th day, the Group C rats received a food reward for successfully completing the maze; on day 12, Group C demonstrated the same knowledge of the maze as Group A that had been reinforced from day 1 Tolman argued that these rats demonstrated latent learning--learning that is not evident when it first occurs. Tolman further argued the rats developed a cognitive map--a mental representation to understand complex patterns (e.g., the maze). He suggested cognitive maps develop naturally as a result of experience, even in the absence of any response or reinforcement. personal example:___________________________________________________________________ COGNITIVE PROCESSES IN LEARNING Insight and Learning Wolfgang Köhler, a Gestalt psychologist, placed chimpanzees in a cage and placed pieces of fruit so they were visible but out of the animals’ reach. Many of the chimps overcame obstacles to reach the food easily. Köhler introduced harder tasks the chimps again solved, leading him to suggest they were NOT demonstrating the results of gradually formed associations of responses to consequences NOR practicing trial and error. Instead, Köhler believed the chimps suddenly saw new relationships that were never learned in the past. They had insight--an understanding of the problem as a whole. Köhler’s observations about the animals’ problem-solving behaviors: 1. Once a chimp solved a problem it would immediately do the same thing if faced with a similar situations. 2. The chimps rarely tried a solution that did not work. 3. the chimps often reached a solution quite suddenly. Some cognitive psychologists now think insight results from a “mental trial and error”--envisioning course of action, mentally simulating results, comparing to imagined outcomes of other alternatives, then settling on course of action deemed most likely to aid complex problem-solving and decision-making. In other words, insight might be a result of learning to learn--”instantly” applying previous experiences to new ones. personal example:___________________________________________________________________ COGNITIVE PROCESSES IN LEARNING Observational Learning: Learning by Imitation Watching what another person does can affect your own behavior. Albert Bandura conducted The Bobo Doll Experiment on a group of young children to determine the effects of observational learning (social learning)--acquiring knowledge by watching others perform a task. This experiment proved to be one of the most influential studies in psychology. What did he find? The children who had seen the adult rewarded for abusing and yelling at the Bobo doll imitated the aggressive adult the most. They received vicarious conditioning--learning by seeing or hearing about the consequences of other people’s behavior. The children who saw the adult punished tended not to perform aggressive behaviors, but they still learned the behaviors. Observational learning can occur even when there are no consequences. Many children in the neutral condition also imitated aggressive behaviors. Bandura’s Bobo study concluded that modeling--the imitation of behavior directly observed--plays an important role in influencing children’s behavior. His work is the basis for the campaign against media violence because of the negative impact such exposure can have on children. There are important criticisms of Bandura’s work worth noting. The confounding variables of previous exposure to violence and previous exposure to the Bobo doll toy raise legitimate questions about the degree to which social learning theory influences our behaviors. personal example:___________________________________________________________________