Credible accounts of causation in complex rural contexts

advertisement

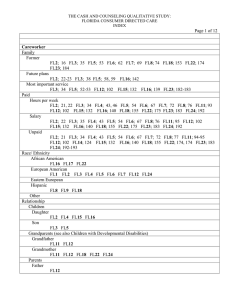

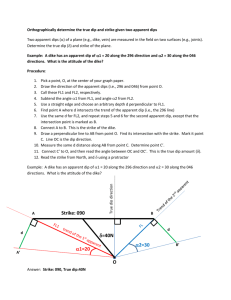

Finessing the qual-quant distinction in research and evaluation Action research into methodologies for assessing complex rural transformations in Malawi and Ethiopia. James Copestake and Fiona Remnant 27 January 2015 ART project webpage: go.bath.ac.uk/art 1 Origins of the presentation • Paper submitted based on Working Paper: Assessing Rural Transformations: Piloting a Qualitative Impact Protocol in Malawi and Ethiopia • Response: “On first (very quick) reading, this paper seems somewhat embedded in a quantitative paradigm (albeit with some narrative data).” • Invitation to resubmit, reflecting more on qual/quant distinction, e.g. What is a quantitative or qualitative paradigm? 2 Summary • Creative mixing of qualitative and quantitative research is aided by deconstructing and reconstructing the distinction between them. • One approach is to review framing and data codification within any research process (from initial scoping to use). • This departs from the norm of assuming mixed method research partitions (or nests) self-contained qual and quant. methods. • To explore this we use the case study of our experience in designing and testing a qualitative research protocol for impact evaluation of NGO livelihood improvement and climate adaptation projects in rural Ethiopia and Malawi. 3 Key concepts (1): framing “If calculations are to be performed and completed, the agents and goods involved in these calculations must be disentangled and framed. In short a clear and precise boundary must be drawn between the relations which the agents will take into account and which will serve in their calculations and those which will be thrown out…” M Callon, editor. (1998) The Laws of the Markets, Oxford: Blackwell. Page 16. 4 Key concepts (2): codification “… the distinction between quantitative and qualitative enquiry hinges less on the source of information than on the point at which information is codified, or otherwise simplified. Early codification permits rigorous statistical analysis, but at the same time entails introducing restrictive assumptions which limit the range of possible findings.” J Moris and J Copestake (1993) Qualitative enquiry for rural development: a review. London: ITDG. Page 1. 5 Key concept (3): partitioning • Maintain a categorical distinction between quant and qual approaches or paradigms. Identify ways in which they can be mixed: – In parallel (triangulation) or – In sequence (e.g. qual pilot -> quant survey -> qual case study etc). • NOT the main focus here – as this is the dominant discourse for mixed methods, and the focus here is on one integrated method. 6 Analytical framework Simplified reality (with respect to time, space, ontology) to facilitate quantification Framing (selection) Codification Research activities through time (initial scoping, data collection, analysis, dissemination) Reframing and decodification (synthesis) Infinitely complex reality 7 Case study: the ART project 8 (a) Initial scoping • How to assist NGOs gather timely and credible data for internal and external use on the impact of their projects? • Three strands to the research: 1. Monitoring 2. Qualitative assessment 3. Meta analysis of the usefulness of the methodology. • Focus here only on Strand 2, piloting the qualitative assessment tool (the QUIP) 9 Projects (X) Impact Indicators (Y) Confounding Factors (Z) Project 1. Groundnut value Food production Weather chain (Central Malawi) Cash income Climate change Food consumption Crop pests and diseases resilience Cash spending Livestock mortality (Northern Malawi) Quality of relationships Activities of other organisations Net asset accumulation Market conditions Project 2. Diversification and Project 3. Malt barley value chain (Southern Ethiopia) Project 4. Diversification and Overall wellbeing resilience Other? Demographic changes Health shocks … more? (Northern Ethiopia) 10 (b) Data collection • Two independent local field researchers, without any knowledge of the project (blinding). Four-six days of semistructured interviewing, two days of focus group discussions. • Sample selection based on lists from separate quantitative monitoring of key household level indicators (IHM). • Data collection instruments structured around any changes since project inception, split by life/livelihood domain: open questions followed by closed questions for each domain. 11 (c) Analysis • Responses to open and closed questions entered into pre-formatted Excel sheets. • The analyst uses the project theory of change to classify causal statements in the raw narrative data by attribution type: positive/negative explicit, implicit, incidental and unattributed. • Change data (causal statements) are sorted into categories and summarised using simple frequency counts. 12 (d) Dissemination • Short report summarising frequency with which households volunteered explicit, implicit, incidental causal explanations with respect to each impact domain. • Lists of all causal explanations cited more than once. • Appendix providing narrative data (sorted causal statements) 13 Causal Coding Key Change attributed to: Code Explanation Explicit project (positive) 1 Positive change attributed to project and project-linked activities Explicit project (negative) 2 Negative change attributed to project and project-linked activities Implicit (positive) 3 Stories confirming a mechanism by which the project aims to be achieving impact, but with no explicit reference to the project Implicit (negative) 4 Stories questioning a mechanism by which the project aims to be achieving impact, but with no explicit reference to the project 5 Positive change attributed to any other forces that are not related to activities included in the commissioning agent’s theory of change Other attributed (negative) 6 Negative change attributed to any other forces that are not related to activities included in the commissioning agent’s theory of change Unattributed (positive) 7 Positive change not attributed to any specific cause Unattributed (negative) 8 Negative change not attributed to any specific cause Other ambiguous, ambivalent or neutral statements 9 Changes with no clear positive or negative implications Other attributed (positive) 14 Responses to closed questions Code Main respondent Age of respondent 1. Food Production 2. Cash income 3. Purchasing power 4. Food consumption 5. Assets LL1 Female 61 = + - - + LL2 Female 31 + + + + + LL3 Male 49 + + + + + LL4 Female 22 + + + + + LL5 Female 31 - - - = - LL6 Female 22 + + + + - LL7 Male 26 + + + + + LL8 Male 43 + + + + + 15 Frequency of narrative causal statements Positive changes reported by households and focus groups 1 Project explicit Food production LL2, LL5, LL6, LL7, LL8 FL3, FL4 Cash income LL2, LL5, LL6, LL7 FL1, FL2, FL3, FL4 Purchasing power LL2, LL6, LL7, LL8 FL1, FL2, FL3, FL4 Food consumption LL2, LL7, LL8 FL4 Relationships LL2, LL5, LL7, LL8 FL4 Asset accumulation LL7, LL8 FL1, FL4 Notes: LL1 to LL8 refer to individual household codes 3 Project implicit LL3, LL6 FL4 5 Other LL4 LL3, LL4, LL7, LL8 LL4, LL7 LL3 LL4 LL3 LL4 LL3 LL1 LL,4 FL3 LL2, LL4 7 None FL1 to FL4 refer to focus groups: FL1 Younger women; FL2 Older women; FL3 Older men; FL4 Younger men. 16 Frequency of narrative causal statements Negative changes reported by households and focus groups Attribution Food production 2 Project explicit 4 Project implicit FL1, FL2, FL3 6 Other LL5 FL1, FL3 Cash income LL6 FL3, FL4 LL1, LL5 Purchasing power FL2 LL1, LL5 FL1, FL3 Food consumption FL1, FL2 LL1 Relationships Asset accumulation 8 None FL1, FL2 LL5 FL2 17 Drilling into narrative causal statements Section C: Food Production & Cash Income 3. Activities that implicitly corroborate the project’s theory of change (positive) LL3 LL3 LL4 LL6 LL7 4. Activities that implicitly corroborate the project’s theory of change (negative) The respondent said that they rely on farming both irrigation as well as rainfed. In the past, they used to rely on food for work but now they are growing their own food because they were inspired by their friends who were farming and doing better than them. According to the Respondent, they used to rely on piece work as a main source of income but now they grow cassava, Groundnuts and sell these. This has been so because their friends encouraged them to do farming so that their welfare improves also. She also reported that she occasionally sells her maize to supplement her income. On new activities taken to help produce more food she said: "…I She however bemoaned the low rent in several fields each season which has also helped to increase prices that itinerant vendors offer food production…" for their crops saying this reduces their profit margin. They however reported that they are employing more piece work workers to work on their farms because they are mostly engaged in other activities like attending to customers in their tea room business. They said that employing several temporary workers is 18 therefore something that they are doing differently from others Drivers of change Drivers of positive change Food Production LL2, LL5, LL6, LL7 SHA support with groundnut crop (Support to grow Groundnut from SHA in the form of free seeds, advice and/or credit) SHA 'pass on' LL7, LL8 livestock programme (pigs and goats provided by FIDP and SHA; further benefits accruing from livestock reproducing) SHA/FIDP advice LL8, LL7 on irrigation FL3 farming (Advice and some equipment provided by FIDP and SHA - treadle pumps, watering Cash Income Purchasing power LL1, LL2, LL5, LL6, LL7, FL1, FL2, FL4 LL2, LL6, LL7 FL1, FL2, FL4 LL8, LL5, LL6 FL2, FL4 FL3 Food Consumption LL2, LL8 FL4 Relationships Assets FL3, FL4 FL1 FL1, FL4 19 Most widely cited drivers of change Domain Positive Project 1: groundnut seed, Malawi (n=8,4) Food production NGO support for groundnut crop (4,0)* NGO advice on making manure (2,2)* NGO advice on small-scale irrigation (2,1)* Cash NGO support for groundnut crop (5,3)* Income NGO pass-on livestock programme (3,2)* NGO support for farming as a business (3,0)* Cash spending NGO support for groundnut crop (5,3)* NGO support for farming as a business (3,0)* Village savings and loan groups (3,0) Food consumption NGO support for groundnut crop (2,1)* Quality of relationships NGO support for farming as a business (1,1)* Net asset accumulation NGO support for groundnut crop (2,0)* Asterisks indicate those drivers that explicitly or implicitly support or negate project theory Negative Low sale price for crops (1,3)* Low sale price for crops (2,3)* Increased prices, including food (0,3) Increased prices, including food (0,2) Economic hardship (0,2) 20 Meta analysis: (re)framing and (de)codification steps within the research process 21 (a) Scoping Key step in terms of broad framing of the research • Who? – Feedback from intended beneficiaries up the ‘aid chain’. • What? – Reality check on agencies’ theory of change (confirmatory and exploratory evaluation). • Why? – Learning and accountability. • How? – Sample in-depth interviews and focus groups alongside project monitoring. • When? – single visit with recall over specified period. 22 (b) Data collection • Interviews framed by semi-structured questionnaire arranged in line with predetermined domains of impact. • Open (not codified) in terms of potential sources of change: field worker and respondent blind to project theory to reduce confirmation bias. But dependent on field worker’s skill in summarising open conversation. • Closed questions using Lickert scales to finish each section - inviting respondent to participate in codification. 23 (c) Analysis • Post-hoc codification according to prior categories of impact: positive/negative; explicit, implicit, incidental, unattributable. • Triangulation of open and closed question responses. • Synthesis through identification of patterns in drivers of change, and relating these to wider context. 24 (d) Dissemination and use • Standard format of short reports with summary tables (codification) that can be visually and rapidly be absorbed (synthesis) by staff. • These also signpost how they can decodify by drilling deeper into the sorted narrative data in annexes. • Triangulation with data obtained through monitoring and other methods (not covered here) 25 Conclusion • Need for an alternative language in order to transcend the qual/quan dichotomy. • Synthesis (decodification and reframing) can take place within a research method. • This is a form of internal triangulation informed by comparing different ways of framing and coding data from the same source. 26