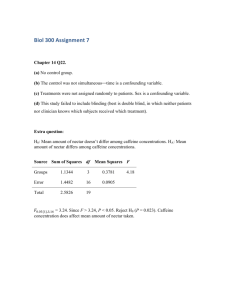

Caffeine Related Disorders

advertisement

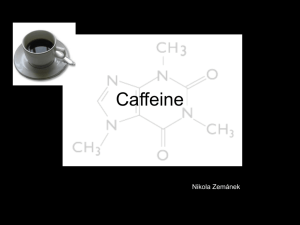

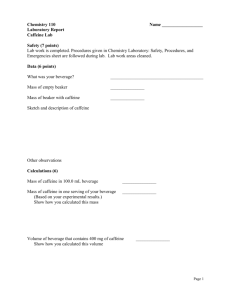

Caffeine-Related Disorders Medscape: Author: R Gregory Lande, DO, FACN; Chief Editor: Stephen Soreff, MD Background Caffeine is the world's favorite psychoactive substance. Only petroleum exceeds coffee as a globally traded commodity, and commerce and history of the United States are closely linked to tea consumption. Soft drinks now rank as the most popular beverage in the United States, and most contain caffeine. Beverage trade groups estimate the annual per capita soft drink consumption at 56 gallons. Research and worldwide beverage history confirm the safety of moderate caffeine consumption in healthy individuals. The universal appeal of caffeine is related to its psychostimulant properties. In a healthy person, caffeine promotes cognitive arousal and fights fatigue. These same activating properties can produce symptomatic distress in a small subset of the population. Susceptibility to this symptomatic distress is broadly determined by 3 factors—the dose consumed, individual vulnerability to caffeine, and preexisting medical or psychiatric conditions (mood disorders in particular) that are aggravated by mild psychostimulant use. Case study Brenda arrived at the doctor’s office a full hour early. The receptionist greeted Brenda and then handed her the typical questionnaires for new patients. Brenda nervously filled out the forms and squirmed uncomfortably in her seat. Finally, the receptionist invited Brenda to meet with the doctor. The doctor began the interview with an open-ended question that granted Brenda the opportunity to rapidly discuss a several month period of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and restlessness. Through the course of the interview, the doctor learned that Brenda had started college 6 months ago and was struggling to keep up. As her grades slipped, Brenda redoubled her efforts by studying more. Unfortunately, fatigue set in and made her less attentive. The doctor asked a few screening questions about nutrition and substance abuse that revealed an interesting trend. Brenda recognized the ill effects of fatigue and sought a remedy. While some students might turn to more potent and illicit drugs, Brenda chose caffeine instead. She carefully read labels and soon discovered an energy drink with the highest level of caffeine. The energy drink did the trick, at least for a brief period. Brenda soon found that 6 energy drinks in the evening kept her awake and relatively alert. The caffeine excess came at a cost though, measured in terms of persisting insomnia, nervousness, and mood fluctuations. Those symptoms actually worsened her test performance leading a friend to suggest she visit a doctor. Pathophysiology Caffeine is a xanthine derivative. It acts by pharmacologically stimulating the CNS, heart, voluntary muscles, and gastric acid secretion, and it induces diuresis. Caffeine is rapidly absorbed. Peak plasma levels are achieved in about 1 hour. Caffeine saturates all body tissues and fluids, including breast milk. The half-life of caffeine is 4-6 hours. The amount of caffeine in coffee and tea varies based on brewing times and methods. General guidelines for beverage caffeine content include the following: Brewed coffee (8 oz) - 120 mg Instant coffee (8 oz) - 70 mg Iced tea (8 oz) - 60 mg Hot tea (8 oz) - 60 mg Caffeinated soft drink (12 oz) - 50 mg The average daily consumption of caffeine among Americans is 219 mg. [1] Adults receive nearly three quarters of their daily caffeine from coffee. Children receive one half of their caffeine from soft drinks. Energy drinks represent a fast-growing beverage market. A combination of caffeine and herbal ingredients are touted as providing an energy boost. Energy drinks vary in the amount of caffeine included in their formulations and can range from around 50-300 mg. Although it sounds more exotic in some drinks, guaranine is caffeine . Consumers seeking the activating qualities of caffeine in pill form can find many preparations, the more well known having 200 mg. Individuals worldwide consume about 76 mg of caffeine per day. Caffeine symptoms appear to be dose-related. Most people experience no behavioral effects with less than 300 mg caffeine. Sleep is more sensitive and can be disrupted by 200 mg caffeine. At doses exceeding 1 g per day, susceptible individuals experience toxic effects. Epidemiology Frequency - United States Prevalence rates for caffeine-induced psychiatric disorders have not been well established. Mood disorders and other substance abuses coexist with caffeine disorders. Some studies report 50% comorbidity. [2, 3] The 4 caffeine-induced psychiatric disorders include caffeine intoxication, caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, caffeine-induced sleep disorder, and caffeine-related disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). Diagnostic criteria for the 4 psychiatric disorders are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).[4] DSM-IV-TR criteria for caffeine intoxication o Recent consumption of caffeine, usually in excess of 250 mg (more than 2-3 cups of brewed coffee) o Demonstration of 5 or more of the following signs during or shortly after caffeine use: Restlessness Nervousness Excitement Insomnia Flushed face Diuresis Gastrointestinal disturbance Muscle twitching Rambling flow of thought and speech Tachycardia or cardiac arrhythmia Periods of inexhaustibility Psychomotor agitation o The above symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. o The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder, such as an anxiety disorder. DSM-IV-TR criteria for caffeine-induced anxiety disorder o Prominent anxiety predominates in the clinical picture. o There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings suggesting that the anxiety developed within 1 month of caffeine intoxication or withdrawal or that medications containing caffeine are etiologically related to the disturbance. o The disturbance is not better accounted for by an anxiety disorder that is not substance-induced. o The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium. o The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. DSM-IV-TR criteria for caffeine-induced sleep disorder o A prominent disturbance in sleep occurs that is sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention. o There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the sleep disturbance is the direct physiological consequence of caffeine consumption. o The disturbance is not better accounted for by another mental disorder. o The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium. o The disturbance does not meet the criteria for breathing-related sleep disorder or narcolepsy. o The sleep disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. DSM-IV-TR criteria for caffeine-related disorder NOS o This includes any caffeine disorder other than those previously listed. o Symptoms of caffeine withdrawal that are not currently an officially recognized diagnosis are present. Caffeine withdrawal is listed in DSM-IV in the appendix, "Criteria Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study." Based on clinical experience, further research, and DSM-IV task force review, the diagnosis may become officially recognized. Symptoms may begin 6-12 hours after stopping or decreasing consumption, peak in 1-2 days, and persist for a week. The research criteria include the following: o o Prolonged daily use of caffeine Abrupt cessation of caffeine use or reduction in the amount of caffeine used, closely followed by headache and one or more symptoms that include marked fatigue or drowsiness, marked anxiety or depression, and nausea or vomiting. o The symptoms in the criteria listed above cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. o The symptoms are not due to the direct physiologic effects of a general medical condition (eg, migraine, viral illness) and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder. Apart from the caffeine-induced psychiatric disorders, clinicians must consider the influence of psychostimulants on other mental disorders. o Individuals who abuse other substances commonly consume large quantities of caffeine. o People with schizophrenia typically consume large amounts of caffeine. [5] o Caffeine may contribute to agitation, irritability, and, possibly, interfere with antipsychotic medications. On the other hand, caffeine can markedly elevate blood levels of antipsychotic medications, increasing the probability of adverse effects. The possible mechanism explaining this finding is that caffeine and antipsychotic medications both compete for metabolism at the hepatic P-450 isoenzyme system. Patients with bipolar disorder are at risk for an exacerbation of manic symptoms when they consume large amounts of caffeine. This is due both to its direct psychostimulant properties and secondary to increase renal excretion of lithium. [6] o Severe depression is correlated with high blood-caffeine levels. o People with panic disorders are at increased risk of precipitating an anxiety attack after caffeine use. [7] Diagnosis of any caffeine-related disorder begins with clinical awareness. o Beverage caffeine is such a common component of social activity that its consideration as a psychostimulant often is neglected. o Too many clinical histories fail to record caffeine use. A complete caffeine history includes doses associated with beverages and medications. o Several over-the-counter analgesic, sinus, and weight loss compounds contain caffeine. o There are preparations that exploit caffeine's alerting affect. They are marketed as stimulants or "stay-awake" preparations, and they can contain 200 mg of caffeine. Physical The observable signs associated with caffeine consumption are dose dependent. For most individuals who consume caffeine in the average range, the physical stigmata will include arousal signs. Expect to see nervousness, elevated heart rate, increased respiratory rate, flushed face, and an exaggerated startle response. Caffeine is a mild diuretic and may contribute to vague gastrointestinal complaints. In rare cases where an individual's dose exceeds 1 g/d, the picture changes. Gross muscle tremors, highly disorganized speech, and possible arrhythmias herald a more sinister outcome. [8] Mental Status Examination o Many of the effects of caffeine consumption are expressed in behavioral manifestations. The most common is anxiety, with its associated fidgetiness, distractibility, poor eye contact, hesitating speech, and prolonged bursts of energy. o Caffeine's effect on mood is complicated and not fully understood. Although initially it may promote some improvement in mood, notably identified by some slight euphoria or focused attention, this pattern may give way to a chronic dysphoria. This mildly depressed state may be a consequence of withdrawal. o Any complaint of sleep difficulty should include a careful assessment of beverage consumption. o Caffeine would not produce perceptual problems such as hallucinations. o Caffeine consumption does not produce alterations in thinking, such as delusions. o Caffeine consumption does not cause disorientation, memory problems, mental confusion, impairment in judgment, or problems with abstract thinking. o The Mental Status Examination should include a safety assessment, addressing any potential risk of suicide or homicide. Caffeine by itself would not raise safety concerns, but the associated mood disorders could. Patient Education Every individual entering the medical system should, at some point, receive a nutritional assessment. This can be a brief intervention; however, at least part of the inquiry should seek to understand beverage consumption. This opens the opportunity to address any excessive reliance on a single beverage, be it alcohol, caffeine, or other products. o Clinicians should attempt to quantify each beverage type consumed per day. To assist data collection, the person can be instructed to keep a daily log of all liquids consumed. This can be an instructive lesson for the individual, who might discover, for example, that all liquids consumed in an average day might be caffeinated sodas. This allows the clinician to stress the importance of varying the diet and, most importantly, of adding water in place of other beverages. o Individuals should be further instructed to carefully read labels. Many noncola beverages contain caffeine. Certain medications, such as over-the-counter diet pills, cold medications, and analgesics, also contain caffeine. o Caffeine consumption during pregnancy is generally safe, according to the Organization of Teratology Information Services, if use is restricted to a moderate range not exceeding 300 mg a day. Caffeine will enter breast milk. [10] o Energy drinks are increasingly popular and caffeine is a main ingredient contributing to the sense of arousal. Children and adolescents can consume large amounts of caffeine in pursuit of a "buzz." Even unwitting overconsumption can produce the signs of caffeine intoxication. Parents should encourage children to carefully read the labels and avoid consuming excess amounts of caffeine. [11] o Caffeinated gum is another means of delivering the mild psychostimulant. One type of gum contains 40 milligrams of caffeine. According to one study, the use of caffeinated gum improves performance efficiency and mood. [12] Health conscious patients may wonder if caffeine consumption poses a long-term hazard. Although not entirely a settled matter, a recent study found mortality rates did not increase among coffee drinkers. [13] Regular consumption of caffeine does not seem to increase the risk of hypertension. [14] Family education may be particularly helpful among younger consumers of caffeine. Energy drinks expand the reach of caffeinated beverages to younger individuals. Parents can help explain the risks of excessive use of these popular beverages, perhaps by converting caffeine levels into "cups of coffee" equivalents. Parents can also help explain the side effects associated with caffeine use. See this helpful Web site about Caffeine