American Revolution - vcehistory

advertisement

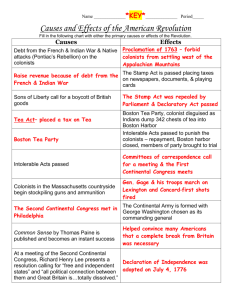

Chapter 3 Breaking with the Past (1773 to July 1776) Tea makes me ANGRY! At the beginning of 1773 the British East India Company – the world’s largest corporation at the time – was suffering due to an oversupply of and a lack of demand for tea in Europe. So, they encouraged the British government to pass a Tea Act in May 1773. The Tea Act would give them easy access to the colonial markets by avoiding local merchants and selling to the cities at a lower price than the French and Dutch could. It was not a tax, they already had the Townshend Duties for that. With tea costs lowered Lord North didn’t expect the protest that resulted. However tea traders, whose profits were threatened, were supported by citizens who participated in an anti-British boycott both in households and at the ports (e.g. in New York). Edenton Ladies The Edenton Tea Ladies get a bit crazy The Tea Party The arrival of three tea-bearing ships in Boston Harbour in late-November 1773 prompted a standoff between local gangs, the shipping companies and the royal governor Thomas Hutchinson. When the Dartmouth arrived Samuel Adams and the Boston Son’s of Liberty called several well-attended meetings and ordered that the tea not be unloaded. Gangs watched over the ships, while Hutchinson worked to ensure that the tea made it to shore. The ship waited there for 20 days, being joined by the Eleanor and Beaver ships. Rumour has it, Samuel Adams started the boycotts because he was jealous that tea was outselling his own ale.* *Rumour fabricated by Mr Elliott* Eleanor and Beaver The Forgotten Ships Eleanor the Ship Beaver the Ship Eleanor Roosevelt A Beaver The Tea Party Under the terms of the Tea Act the Dartmouth was required to arrive within 20 days. With the deadline approaching on 16th of December, Samuel Adams called a town meeting with 6000 people attending. After dark a band of men – perhaps as many as 50 – dressed up (poorly) as native American’s, boarded the ship and threw 342 chests of tea overboard. This tea was worth, in modern terms, approximately $1 million dollars so it was no laughing matter. Unless you feel like laughing, in which case, do so. *False, fabricated by Mr Elliott, beer not made until 1984* They wish their costumes were this good. Rumour has it that the men involved had several mugs of Samuel Adams’ finest ale before going nuts* Tealapalooza! The Boston Tea Party inspired a similar incident at Hubbards Wharf, Boston in March, 1774 and protests in New York, Philadelphia and Charleston. However, no other colony responded as strongly or destructively as Massachusetts. Many criticised the vandalism, with Benjamin Franklin calling it ‘an act of violent injustice’ and John Dickinson urging them to pay for the lost tea. A tremendous cartoon about the new, even stupider Tea Party ‘This happened and we all let it happen’ – Peter Griffin We take a moment away from our studies to explore just how stupid Sarah Palin is and how funny Tina Fey is. The Coercive Acts The British Parliament was very angry about all this and responded by introducing several ‘coercive acts’. Lord North told MPs ‘the Americans have tarred and feathered your subjects, plundered your merchants, burnt your ships, denied all obedience to your laws and authority… we must risk something; if we do not, all is over’ Change – the British will fight back! Step upwards ye bitches The Coercive Acts North started with the Boston Port Act on 30th of March 1774, closing the docks to all private shipping and using warships to block the entrance to the harbour. Then on the 20th of May, the Massachusetts Government Act was passed, revoking the colony’s charter and replacing Thomas Hutchinson with a military commander in General Thomas Gage. Boston was now under military rule until they had paid their debt. Then came the Administration of Justice Act on the same day, which allowed the governor to send persons charged with murder to trial in England away from the hostile juries and judges of New England. By this stage the British had interfered with the Economic, Political and Legal rights of Bostonians. The conflict would only increase. Lord North: He ain’t messin’ aboot The Coercive Acts The Coercive Acts The fourth and final act of coercive legislation was an adjustment to the 1765 Mutiny (Quartering) Act with governors now allowed to forcibly take possession of halls, barns and vacant buildings. The Quebec Act was not a part of the Coercive Acts but it was still very unpopular. The legislation expanded Quebec (in British Canada) while restricting American expansion westwards. This effectively ‘boxed’ the American’s in like they were prior to the French-Indian War. It also brought those nasty French Catholics back in contact with the Americans and the British accommodated this. The Quebec Act Protestant New Englanders were worried about the influence of French Catholicism resulting in ‘lands plundered of thithes for the support of a Popish clergy’ (that’s not even French). Game of Thrones est vraiment juste un rip-off du traditionnel jeu de passe-temps Québec Scones (this is). The other concern was that, like George III’s Proclamation Act, the Quebec Act would prevent the American’s from ever expanding west past the Appalachian mountains. The true motives of the revolution start to be questioned here as we find the famous leaders like George Mason, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry fear for the loss of lands they had claimed. To help New Englanders assimilate with their northern neighbours, this magazine replaced National Geographic in all doctors waiting rooms.* *Rumour fabricated by Mr Elliott* Dunmore’s Private War As the British Parliament was discussing the Quebec Act, trouble was brewing on the Virginia frontier. War had broken out between colonists and the areas native tribes, sparked by settlers moving into newly-claimed lands in the west. In October 1773, a war party of Delaware, Cherokee and Shawnee natives, fed up with these intrusions, tortured and murdered a group of young men and boys. This led to a rise in conflict between settlers and ‘Indian Hunters’. This is where it all happened He could have Dun-more to harbour good relations with the natives. Dunmore’s Private War The worst incident came in April 1774 when 20 Mingo natives were scalped and murdered by Virginia farmer, including the daughter of Logan (who had been peaceful). This led to a war along the VirginiaKentucky frontier. In May, the Virginian governor gave orders for an all-out war on hostile tribes in the west. This was a change as they were actively disobeying the Proclamation Act of 1763. We know this happened because there is a plaque. And a book British rule in Boston At the start of 1775 Boston was under the control of the British military governor, General Thomas Gage, and his regiment. He was initially greeted warmly. However, Gage began issuing arrest warrants for leading radicals and closed the port and continued the ban on the colonial assembly. This was seen as a British attempt to seize back control of the colonies. As a result, preparations began for a colonial military response. This is a change as it was a move towards a united American force against the British. However, at that time, the ‘Minutemen’ was not strong enough to fight the British. There is nothing funny about Thomas Gage The Powder Alarms One of General Gage’s first priorities was to destroy gunpowder stores around Massachusetts. He did this in secret to prevent revolutionary activists from seizing the powder first. The Minutemen responded by strengthening their forces and Committees of Safety were established to warn people of the British troop movements. Paul Revere’s ride is a famous though factually dubious account of anti-British coordination in the colonies. It would be inappropriate for me to joke about this (see Austin Powers) Paul Revere’s ride http://poetry.eserver.org/paul-revere.html Committees of Correspondence While some American colonists were making military and logistical preparations, others were considering how they could build support against the British. The Committees of Correspondence had been active since the mid-1760s and were reactivated by Samuel Adams, reaching a peak in 1774. These committees started letter writing campaigns aimed at resisting the Coercive Acts and other aspects of British rule. The activities were mostly confined to the urban middle and upper classes. People in rural towns still looked to their own assemblies and leaders for news and guidance. The Churches also played a role in discussing the ‘evils’ of ‘unrepresented taxation’. This period included change because now people were talking about separation and revolution. A letter from Samuel Adams in 1772 Towards a Congress There was also revolutionary activity in the tows, villages, rural outposts and on the frontier. This occurred through the traditional town meetings, where radical ideas were expressed. Meetings drafted documents about nonimportation agreements and started to draft local milita and supplies such as weapons, tools and food. In addition to these organised activities there was an open-defiance, a continuation of revolutionary activity, by mobs who forced the closure of several county court, especially in Massachusetts. Worcester County Court http://allthingsliberty.com/2013/02/the-true-start-of-the-american-revolution/ Inter-Continental Congress Samuel Adam’s push for an inter-colonial meeting was achieved at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September, 1774. The congress consisted of 55 men from 12 colonies (Georgia chose not to attend) with many of the revolutionary figures including the Adams cousins, George Washington, Patrick Henry Lee and John Jay. The congress argued the Coercive Acts. Some, particularly the southern states, were critical of the Bostonians behaviour. However, they agreed on a number of key principles, including a new outline of grievances and passed the Articles of Association. http://www.masshist.org/revolution/congress1.php Lexington-Concord History and folklore agree that the first shots of the Revolutionary War were fired in Lexington, Massachusetts in April, 1775. The conflict arose when General Gage ordered 700 British troops to march on Concord to find a large gunpowder store. The soldiers met a colonial militia armed with sticks and scythes (crop blades). The British soldiers were ordered not to fire but one soldier did. This became known as the ‘shot heard around the world’. The British advanced and killed eight colonial militiamen. The warning systems of the local Committee of Safety were alerted and the battle continued with a church being set on fire and more fighting. At the end of forty-eight hours of fighting more than 130 men were dead, most of them British. This was a change as the Americans were actively engaged in armed conflict with the British. Second Continental Congress The Continental Congress met again in Philadelphia in May 1775 with two newcomers being Benjamin Franklin and John Hancock. While this was going on military conflict was happening in Massachusetts and also in New York. Congress resolved to take control of the war effort, declaring the formation of a Continental Army and nominating George Washington as commander-inchief. The appointment was made due to Washington’s military experience but also because he was from a southern colony, Virginia, and they wanted their support. In July 1775 the Congress drafted and released a justification for its military action, the Declaration of Causes and Necessities for Taking up Arms. Back in England, King George III considered the congress an illegal body and refused to read their petitions and declarations, accusing the members of treason. George The Olive Branch Petition Even after the war had started many in the second Continental Congress wanted to reconcile with Britain. Men like Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson did not believe that the Continental Army could win against the powerful British military. The Olive Branch Petition affirmed colonial rights while criticising the king’s ministry for mishandling the colonies. It was signed by revolutionaries like Sam Adams, John Adams, John Hancock, John Jay and Patrick Henry. Privately, most held little hope that the conflict would be resolved. A last gasp attempt at peace Towards Independence Until late 1775 most Americans were reluctant to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. The conversion to independence came gradually in the first half of 1776 with historian Pauline Maier tracing this to a wide range (90) different resolves from different towns, counties and assemblies throughout America. The New Hampshire motion, passed on 5th of January 1776, several days before the first edition of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense included a declaration of independence and the first written constitution in the new nation (change). Key statement ‘… the delegates for this colony in the Continental Congress be empowered to concur with the delegates in the other Colonies in declaring independence’. Towards Independence In May 1776 the Continental Congress moved that all colonies should establish state governments (change). Delaware, New Jersey, North and South Carolina, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Maryland all did by the end of the year. Georgia, New York and Vermont followed in 1777. Their draft constitutions included many liberal innovations but also property qualifications and exclusions of women, slaves, natives and indentured servants from elections. All states except New York and Virginia allowed only Protestants to hold public office. Common Sense Town meetings and colonial assemblies were the engines of the American Revolution, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was its manual. The fifty-page booklet sold cheap (two shillings) and appealed to the masses, gaining support for the ideological justification for revolution, liberty. Paine was well versed in the enlightenment ideas of the time and played a major role in the French revolution soon after. Common Sense Common Sense addressed three broad themes: the flawed monarchy, the situation in the colonies and the future of America. It was radical but not original, the ideas were being discussed across Europe as well. What Paine did best was to use language, rhetoric and analogies that appealed to ordinary Americans. Not everyone was a fan with John Adams calling him a ‘a poor, ignorant, malicious, short-sighted crapulous mass’ (a bit mean?). Declaration of Independence The ideas of Common Sense, along with all of the revolutionary activity, led to an increased call for independence during the spring of 1776. A group within the Continental Congress, with Samuel and John Adams and Richard Henry Lee the leaders, began to push actively for separation. Lee introduced a motion (from his home colony of Virginia) to declare the ‘United Colonies free and independent States’ on 7th of June but no vote could proceed because a number of delegates had not been authorised by their assemblies to vote for or against. Declaration of Independence Anticipating the probably success of Lee’s motion, congress decided to prepare a suitable declaration of independence. They asked Virginian Thomas Jefferson to write the first draft, as he had a good knowledge of political philosophy (e.g. enlightenment ideas) and the situation in America. On 28 June the committee presented the draft to Congress, which heavily edited Jefferson’s draft, particularly his condemnation of the slave trade. The Declaration of Independence was passed by Congress on July 4, 1776.