New Hampshire VTE 080312 - Foundation for Healthy Communities

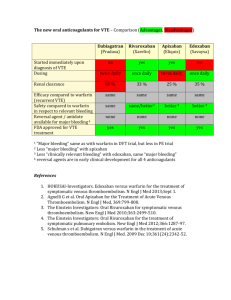

advertisement

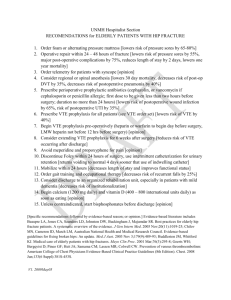

Prevention and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism National Performance Measures And Recent Guidelines Dale W. Bratzler, DO, MPH Professor and Associate Dean, College of Public Health Professor of Medicine, College of Medicine Chief Quality Officer – OU Physicians Group University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Dale W. Bratzler, DO, MPH QIOSCAugust Medical Director 3, 2012 Outline • The problem – VTE in US hospitals • Need for national performance standards • Update on National Guidelines for Prevention of VTE • Strategies for prevention of VTE 2 Venous thromboembolism (VTE) = Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary embolism (PE) “The best estimates indicate that 350,000 to 600,000 Americans each year suffer from DVT and PE, and that at least 100,000 deaths may be directly or indirectly related to these diseases. This is far too many, since many of these deaths can be avoided. Because the disease disproportionately affects older Americans, we can expect more suffering and more deaths in the future as our population ages–unless we do something about it.” Annual Incidence of VTE in Olmsted County, MN: 1966-1995 1,200 Men 1,000 800 600 Women 400 200 Age group (yr) 85 0 014 15 -1 20 9 -2 25 4 -2 30 9 -3 35 4 -3 40 9 -4 45 4 -4 50 9 -5 55 4 -5 60 9 -6 65 4 -6 70 9 -7 75 4 -7 80 9 -8 4 Annual incidence/100,000 By Age and Gender 5 Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism Introduction • VTE Remains a major health problem – In addition to the risk of sudden death • 30% of survivors develop recurrent VTE within 10 years • 28% of survivors develop venous stasis syndrome within 20 years Goldhaber SZ. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:93-104. Silverstein MD, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:585-593. Heit JA, et al. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:452-463. Heit JA. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;17:71-92. Heit JA, et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1102-1110. 6 Risk of DVT in Hospitalized Patients No prophylaxis + routine objective screening for DVT Patient group DVT incidence Medical patients 10 - 20 % Major gyne/urol/gen surgery 15 - 40 % Neurosurgery 15 - 40 % Stroke 20 - 50 % Hip/knee surgery 40 - 60 % Major trauma 40 - 80 % Spinal cord injury 60 - 80 % Critical care patients 15 - 80 % 7 Associated Illnesses that are a Consequence of VTE events • Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension – Mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mm Hg that persists 6 months after PE – 2-4% of patients after PE • Post-thrombotic syndrome – Calf swelling and skin pigmentation; venous ulceration in severe cases • Up to 43% of patients within 2 years – most mild Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Lancet. 2012 May 12; 379:1835-46. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism • The majority (93%) of estimated VTE-related deaths in the US were due to sudden, fatal PE (34%) or followed undiagnosed VTE (59%) For many patients, the first symptom of VTE is sudden death! How many of those patients with sudden death in the hospital or after discharge attributed to an acute coronary event actually died of acute pulmonary embolism? Heit JA, Cohen AT, Anderson FA on behalf of the VTE Impact Assessment Group. [Abstract] American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting, 2005. 9 National Body Position Statements • Leapfrog1: PE is “the most common preventable cause of hospital death in the United States” • Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)2: Thromboprophylaxis is the number 1 patient safety practice • American Public Health Association (APHA)3: “The disconnect between evidence and execution as it relates to DVT prevention amounts to a public health crisis.” The Leapfrog Group Hospital Quality and Safety Survey. Available at: www.leapfrog.medstat.com/pdf/Final/doc Shojania KG, et al. Making Healthcare Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. AHRQ, 2001. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/ White Paper. Deep-vein thrombosis: Advancing awareness to protect patient lives. 2003. Available at: www.alpha.org/ppp/DVT_White_Paper.pdf 10 Annual cost to treat VTE • $11,000 per DVT episode per patient • $17,000 per PE episode per patient • Recurrence increases hospitalization costs by 20% • Complications of anticoagulation • Time lost from work – Quality of life: venous stasis and pulmonary HTN 11 Consequences of Surgical Complications • Dimick and colleagues demonstrated increased costs of care: – – – – infectious complications was $1,398 cardiovascular complications $7,789 respiratory complications $52,466 thromboembolic complications $18,310 Dimick JB, et al. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:531-7. 12 Do venous and arterial diseases have shared risk factors? “…..4 years after surviving a PE, fewer than half will remain free of MI, stroke, PAD, recurrent VTE, cancer or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.” VTE and atherothrombosis have a common pathophysiology that includes inflammation, hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury. Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Lancet. 2012 May 12; 379:1835-46. Inherited risk factors for DVT Group 1 disorders Group 2 disorders • Protein C deficiency (2.5-6%) • Protein S deficiency (1.3-5%) • Antithrombin deficiency (0.57.5%) • Factor V leiden (6%) • Prothrombin (G20210A) (510%) • Elevated VIII, IX, XI • Hyperhomocysteinemia • Arteriosclerosis 14 Acquired Risk Factors Risk Factor Attributable Risk Hospitalization/Nursing home 61.2 Active malignant neoplasm 19.8 Trauma 12.5 CHF 11.8 CV catheter 10.5 Neurologic disease with paresis 8.2 Superficial vein thrombosis 4.3 Varicose veins/stripping 6 Many others…. Being in the hospital is the greatest risk factor for VTE! 15 Risk Factors for DVT or PE Nested Case-Control Study (n=625 case-control pairs) Surgery Trauma Inpatient Malignancy with chemotherapy Malignancy without chemotherapy Central venous catheter or pacemaker Neurologic disease Superficial vein thrombosis Varicose veins/age 45 yr Varicose veins/age 60 yr Varicose veins/age 70 yr CHF, VTE incidental on autopsy CHF, antemortem VTE/causal for death Liver disease 0 5 10 15 20 25 50 Odds ratio 16 Independent Risk Factors for VTE after Major Surgery*: Olmsted County 1988-97 (n=163) Risk Factor OR 95% CI P-value Age (per 10 years) 1.26 1.07, 1.50 0.007 BMI (kg/m2, per 2-fold increase) 2.95 1.49, 5.82 0.002 ICU Length of Stay > 6 Days 3.97 1.46, 10.80 0.007 Central Venous Catheter 2.46 1.21, 5.03 0.013 Immobility Requiring Physical Therapy 2.18 1.17, 4.06 0.014 Varicose Veins 1.87 1.08, 3.23 0.025 Any Infection 1.68 1.01, 2.82 0.046 Anticoagulation Prophylaxis 0.27 0.12, 0.59 0.001 *Controlled for Surgery Type, Active Cancer, and Event Year Heit, et al. J Thromb Haemost 2005 17 Cases per 10,000 person-years VTE is a Disease of Hospitalized and Recently Hospitalized Patients 1000 VTE 100X more common in hospitalized patients! 100 Recently hospitalized 10 1 Hospitalized patients Community residents Heit JA. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1102 18 Cumulative Incidence of VTE After Primary Hip or Knee Replacement 3.5 Primary hip Primary knee 3.0 2.5 VTE events (%) 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 0 7 14 21 28 35 42 49 56 63 70 77 84 91 Days White RH, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158: 1525-1531 19 Many events occur after hospital discharge. • IMPROVE Registry – 15,156 medical patients admitted to the hospital • 184 patients had VTE events – 45% developed VTE after discharge • Other studies have shown that up to twothirds of VTE events occur in patients after discharge Spyropoulos AC, et al. Chest 2011; 140:706-14. VTE Facts • Almost half of the outpatients with VTE had been recently hospitalized • About half had a length of stay (LOS) of < 4 days 0-29 Outpatients With VTE, % • Less than half of the recently hospitalized patients had received VTE prophylaxis during their hospitalizations Days After Discharge 30-59 60-90 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Medical Hospitalization Only Hospitalization with Surgery Goldhaber S. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1451-2. Spencer FA et al. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1471-5. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism • Despite the well known risk of VTE and the publication of evidence-based guidelines for prevention, multiple medical record audits have demonstrated underuse of prophylaxis Anderson FA Jr, et al. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:591-595. Anderson FA Jr, et al. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1998; 5 (1 Suppl):7S-11S. Bratzler DW, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1909-1912. Stratton MA, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:334-340. 22 Published Audits of VTE Prophylaxis General Surgery Received Prophylaxis No Prophylaxis 280 97/250 (39%) 240 Cases 200 160 120 30/86 (35%) 33/83 (40%) Moderate High 80 40 0 Very High Use of any form of prophylaxis based on level of risk for venous thromboembolism among 419 Medicare patients from 20 hospitals undergoing major abdominothoracic surgery. Measures were implemented for patients at moderate risk (35%; 95% CI, 25-46%), at high risk (40%; 95% CI, 29-51%), and at very high risk (39%; 95% CI, 33-45%). Overall utilization rate for prophylaxis was 38% (95% CI, 33-43%). Bratzler DW, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1909-1912. Thromboprophylaxis Use in Practice 1992-2002 Patient Group Studies Patients Prophylaxis Use (any) Orthopedic surgery 4 20,216 90 % (57-98) General surgery 7 2,473 73 % (38-98) Critical care 14 3,654 69 % (33-100) Gynecology 1 456 Medical patients 5 1,010 66 % 23 % (14-62) How many patients with COPD, CVA, heart failure, pneumonia, etc do you have in your hospital that are not on DVT prophylaxis? 24 Prevention of VTE in Medical Patients Amin A, Stemkowski S, Lin J, Yang G. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5: 1610–6. Prevention of VTE in Medical Patients Amin A, Stemkowski S, Lin J, Yang G. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5: 1610–6. Diagnosis of VTE • D-dimer (rule out only) • Compression ultrasound • CT angiography Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Lancet. 2012 May 12; 379:1835-46. Diagnosis of VTE Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Lancet. 2012 May 12; 379:1835-46. Prophylaxis and Treatment Prophylaxis Modalities • Mechanical – Graduated compression stockings (GCS) (e.g., “white hose”) – Sequential compression devices • Venous foot pumps (currently recommended only for orthopedic surgery in patients with bleeding risk) In most studies, less effective than pharmacologic prophylaxis and patient compliance rates are generally low. Rates of compliance with mechanical forms of prophylaxis in many studies is less than 50% - has become a new target of malpractice litigation. 30 Pharmacologic Prophylaxis • • • • Low-dose unfractionated heparin (LDUH) Low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH)* Fondaparinux* Direct inhibitors of activated factor X – rivaroxaban • Direct thrombin inhibitors – dabigatran • Warfarin • Aspirin *Cleared by the kidneys. 31 Approach to Treatment How long do you treat? Duration of Treatment Evidence Grade First VTE event secondary to a reversible factor (“provoked”) 3 months 1A First idiopathic (“unprovoked) VTE At the end of initial 3-month period In the absence of contraindication During long-term treatment At least 3 months Assess for long-term Rx Long-term Rx Assess risk/benefit balance 1A 1C 1A 1C Recurrent VTE or strong thrombophilia Long-term Rx 1A VTE secondary to cancer 1A 1C Long-term Rx, preferentially with LMWH during the first 36 months, then anticoagulate as long as the cancer is considered “active” Kearon C, et al. Chest 2008; 133 (6 suppl):454S-545S. Do we have to use warfarin longterm? Multicenter, double-blind study, patients with firstever unprovoked venous thromboembolism who had completed 6 to 18 months of oral anticoagulant treatment were randomly assigned to aspirin, 100 mg daily, or placebo for 2 years Becattini C, et al. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1959-67. Development of National Performance Measures to Prevent and Treat VTE 35 Why the need for performance measures? • Despite widespread publication and dissemination of guidelines, practices have not changed at an acceptable pace – There are still far too many needless deaths from VTE in the US • Reasonably good evidence that using performance measures for accountability can accelerate the rate of change 36 37 Venous Thromboembolism Statement of Organization Policy “Every healthcare facility shall have a written policy appropriate for its scope, that is evidence-based and that drives continuous quality improvement related to VTE risk assessment, prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment.” 38 Venous Thromboembolism Characteristics of Preferred Practices General • Protocol selection by multidisciplinary teams • System for ongoing QI • Provision for RA/stratification, prophylaxis, diagnosis, treatment • QI activity for all phases of care • Provider education 39 Venous Thromboembolism Characteristics of Preferred Practices (cont.) Risk Assessment/Stratification • RA on all patients using evidence-based policy • Documentation in patient record that done Prophylaxis • Based on assessment & risk/benefit, efficacy/safety • Based on formal RA, consistent with accepted, evidence-based guidelines 40 Venous Thromboembolism Characteristics of Preferred Practices (cont.) Diagnosis • Objective testing to justify continued initial therapy Treatment and Monitoring • • • • • Ensure safe anticoagulation, consider setting Incorporate Safe Practice 29 Patient education; consider setting and reading levels Guideline-directed therapy Address care setting transitions in therapy 41 Surgical Care Improvement Project First Two VTE Measures Endorsed by NQF • Prevention of venous thromboembolism • Proportion who have recommended VTE prophylaxis ordered • Proportion who receive appropriate form of VTE prophylaxis (based on ACCP Consensus Recommendations) within 24 hours before or after surgery 42 Venous Thromboembolism Technical Advisory Panel (TAP) charge • Vet the 19 potential measures, agreed upon by the Steering Committee, through TAP and The Joint Commission survey processes • Identify a subset of measures that help address the identified gaps within the endorsed VTE domains • Oversee final development and testing of measures for Steering Committee and NQF endorsement consideration 43 6 Refined Measures That Were Endorsed Risk Assessment/Prophylaxis domain Prophylaxis w/in 24 hours of admission or surgery, OR a documented risk assessment showing that the patient does not need prophylaxis Prophylaxis/documentation w/in 24 hours after ICU admission or surgery 44 6 Refined Measures That Were Endorsed Patients w/overlap of anticoagulation therapy At least five calendar days of overlap and discharge with INR > 2.0, or discharge on overlap therapy Patient receiving UFH with dosage/platelet count monitoring by protocol/nomogram Nomogram/protocol incorporates routine platelet count monitoring 45 6 Refined Measures Endorsed (cont.) Treatment/Monitoring Domain (cont.) – Discharge instructions consistent with Joint Commission safety goals (Follow-up Monitoring, Compliance Issues, Dietary Restrictions, Potential for Adverse Drug Reactions/Interactions) Outcome Incidence of potentially-preventable VTE – proportion of patients with hospital-acquired VTE who had NOT received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event 46 New Guidelines and Controversies New Guidelines http://www.chestnet.org/accp/guidelines/accp-antithrombotic-guidelines-9th-ed-now-available ACCP Disclaimer The ACCP recommends that performance measures for quality improvement, performance-based reimbursement, and public reporting purposes should be based on rigorously developed guideline recommendations. However, not all recommendations graded highly according to the ACCP grading system (1A, 1B) are necessarily appropriate for development into such performance measures, and each one should be analyzed individually for importance, feasibility, usability, and scientific acceptability (National Quality Forum criteria). Performance measures developers should exercise caution in basing measures on recommendations that are graded 1C, 2A, 2B, and 2C, according to the ACCP Grading System1 as these should generally not be used in performance measures for quality improvement, performance-based reimbursement, and public reporting purposes. ACCP 9th Edition General Overview • For acutely ill hospitalized medical patients at increased risk of thrombosis, we recommend anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis with LMWH, LDUH, or fondaparinux (Grade 1B) – Mechanical prophylaxis (GCS or IPC) if bleeding or high risk for bleeding • Similar recommendation for critically ill patients ACCP 9th Edition General Overview • For patients undergoing non-orthopedic surgery – Generally recommend the use of a risk assessment tool (Rogers score or Caprini score) to determine need for prophylaxis • Low risk of VTE (Rogers score < 7.0, Caprini score 0) no prophylaxis recommended other than early ambulation Bahl V, et al. Ann Surg. 2010; 251:344-50. Bahl V, et al. Ann Surg. 2010; 251:344-50. Rogers SO, et al. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:1211–1221. Rogers SO, et al. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:1211–1221. ACCP 9th Edition General Overview • Patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery (THA, TKA, or HFS) recommend LMWH, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, LDUH, adjusted-dose warfarin, aspirin (all Grade 1B), or an IPC device (Grade 1C). – Subsequently recommend in THA, TKA, or HFS LMWH the preferred agent (Grade 2B) ACCP Guidelines • The technical expert panel is evaluating new guidelines to consider revisions – No revisions likely before January 2014 – Many of the recommendations in guidelines do not have 1A and 1B grades and remain very controversial – Most hospitalized patients have additional risk factors for VTE Strategies for Improvement 59 Strategies to Improve VTE Prophylaxis • Hospital policy of risk assessment or routine prophylaxis for all admitted patients – Most will have risk factors for VTE and should receive prophylaxis – Preprinted protocols for surgical patients 60 Electronic Alerts to Prevent VTE among Hospitalized Patients • Hospital computer system identified patient VTE risk factors • RCT: no physician alert vs physician alert No. Any prophylaxis VTE at 90 days Major bleeding Control group 1,251 15 % 8.2 % * 1.5 % Alert group P 1,255 34 % <0.001 4.9 % 0.001 1.5 % NS Kucher – N Engl J Med 2005;352:969 61 Electronic Alerts to Prevent VTE among Hospitalized Patients • Among hospitalized patients with risk factors for VTE and not receiving prophylaxis, use of a physician VTE risk alert: – Improved use of prophylaxis by 130% – Reduced symptomatic VTE by 41% – Did not increase bleeding Kucher – N Engl J Med 2005;352:969 62 Improving Compliance with Treatment Protocols • Use of standardized protocols, nomograms, algorithms, or preprinted orders – Address overlap (either 5 days in hospital or discharge on overlap) – When used, UFH should be managed by nomogram/protocol, and the protocol should ensure routine platelet count monitoring Essential Elements for Improvement • Institutional support • A multidisciplinary team or steering committee • Reliable data collection and performance tracking • Specific goals or aims • A proven QI framework • Protocols SHM Resource Room. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 2009. Risk Assessment Prophylaxis Low Ambulatory patient without VTE risk factors; observation patient with expected LOS 2 days; same day surgery or minor surgery Early ambulation Moderate All other patients (not in low-risk or highrisk category); most medical/surgical patients; respiratory insufficiency, heart failure, acute infectious, or inflammatory disease UFH 5000 units SC q 8 hours; OR LMWH q day; OR UFH 5000 units SC q 12 hours (if weight < 50 kg or age > 75 years); AND suggest adding IPC High Lower extremity arthroplasty; hip, pelvic, or severe lower extremity fractures; acute SCI with paresis; multiple major trauma; abdominal or pelvic surgery for cancer LMWH (UFH if ESRD); OR fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC daily; OR warfarin, INR 2-3; AND IPC (unless not feasible) Maynard GA, et al. J Hosp Med 2009 Sep 14. [Epub ahead of print] Maynard GA, et al. J Hosp Med 2009 Sep 14. [Epub ahead of print] Conclusions • VTE remains a substantial health problem in the US • VTE prophylaxis remains underutilized • National performance measures may address both prophylaxis and treatment of VTE across broad hospital populations 67 dale-bratzler@ouhsc.edu