Bike Group Report

advertisement

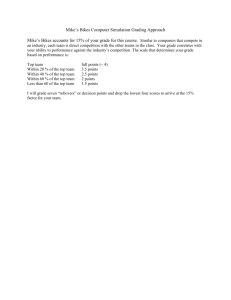

Christina Hughes Grant Parks Sergio Jaramillo Alex Wu Executive Summary Our group was tasked with enacting a pilot bike sharing program on Rice University campus with the intent of gauging the student body’s receptiveness to such a program; in doing so, we examined the viability of a campus wide program. We began the project by examining data compiled and discussed in a previous group’s report. The results from the report were encouraging and affirmed our initial hypothesis: Rice was long overdue for a bike-sharing program. After reviewing the previous research on the subject, we developed a plan for implementation of the pilot program. a.) Select one residential college at which to base the program b.) Procure five bikes from RUPD’s impound, have RUPD’s in-house bike mechanic perform a cursory diagnostic and paint the five bikes in outlandish colors c.) Liaise with the Chief of RUPD, the liability coordinator and the college’s president to discuss the details d.) Implement by the first of November Our group accomplished all of the aforementioned goals expeditiously and the Will Rice-McMurty Bike Share Program was implemented. We created a program which made use of the available resources on campus, provides students with a free alternative to cars, buses and walking, as well as providing students with an environmentally conscious program. These factors, coupled with extensive advertising at Will Rice and McMurtry, garnered an unexpected level of support for the program. Unfortunately, it proved to be more of a boon to students’ quality of life then their desire to reduce carbon footprints, but nonetheless we consider the project to be a success. In a short period of time, with limited resources, we created a viable bike share program which has the potential to be implemented campus wide. Furthermore, we believe that this program has the potential to introduce students to the positive aspects of bike ownership and riding. We envision a campus wide bike share program as a method by which to coax students to eschew the use of fossil fuel burning transport for the environmentally friendly alternative of bike ridership and ownership. Introduction Global warming is a worldwide problem that is affecting our climate conditions and resulting in an increase in the global temperature. Global warming is caused in part by the emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases which build up in our atmosphere and result in the greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect occurs when radiation from the sun reflects from the surface of the Earth and is trapped by greenhouse gases, resulting in a warming of the atmosphere (Energy Information Administration 2009a). The alarming effects of global warming on our planet include increasing severity of storms, rising global sea levels, and the melting of polar ice caps (Energy Information Administration 2009b). The rising sea level is particularly alarming because as the sea rises, many locations where humans live will be flooded and made inhabitable. Many cities, such as Houston and New Orleans are already under the sea level, and any drastic change will place these locations at great risk. The main source of these carbon dioxide emissions comes from burning fossil fuels for electricity generation, transportation, and industry. Global carbon dioxide emissions rose from 23,497.3 million tons in 2000 to 28,962.4 millions tons in 2007 (International Energy Agency 2009a). The problem of global carbon emissions is only getting bigger with projected global carbon dioxide emissions of 42,325 million metric tons in the year 2030 (Energy Information Administration 2008). Road transportation is a major contributor to these carbon dioxide emissions, accounting for 15.9% of global emissions (International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers 2007). This is a major concern because the number of vehicles worldwide has been increasing by about 16 million each year since 1970 (World Resource Institute 1999). Americans are responsible for a large portion of the global warming problem, accounting for 5,769.3 million tons of carbon dioxide out of the global 28,962.4 million tons in 2007 (International Energy Agency 2009a). Most people in the United States drive their automobiles and trucks throughout the day. This is an issue because according to the EPA (2009a), transportation accounted for 29% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2006 and close to two thirds of these emissions come directly from automobiles and trucks (EPA 2009b). The number of vehicles in America has grown, from 225.8 million registered vehicles in 2000 to over 254.4 million in 2007 (Bureau of Transportation Statistics 2007). The increase of vehicles on the road also leads to the issue of oil supply. Oil is a nonrenewable resource that we rely on to fuel our cars. However, as the number of vehicles continues to increase, the rate at which oil is used up also increases. Oil demand has increased and is projected to continue doing so, “rising from around 85 million barrels per day in 2008 to 105 mb/d in 2030, an increase of around 24%” (International Energy Agency 2009b). This increase in demand for oil drives the oil prices up. From 1947 to 1973, the monthly average price of oil was about $20 in June 2009 dollars, and in June 2008, the price of oil had gone all the way up to $124.52 in June 2009 dollars (InflationData 2009). As oil becomes scarcer and more expensive, it will be harder on the nations of the world to depend on oil as the primary fuel of cars. Oil is a big part of business in the city of Houston, Texas, which is home to many oil refineries. Houston is also home to Rice University, as well as home to one of the nation’s most congested traffic systems. Traffic congestion results in commuters spending more time in their cars waiting, and this extra time means fuel is wasted and more carbon dioxide being emitted. In 2007, Houston was found to be ranked 9th in the nation for travel delay, excess fuel consumed, and congestion cost (Texas Transportation Institute 2007). Houston is a city with a heavy reliance on the automobile. In 2006, the Houston-Sugarland-Baytown metropolitan area had a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita value of 5,721, had a total VMT value of 31,508.6 million, and was ranked 5th in the nation for total vehicle miles traveled (Puentes and Tomer 2008). In a city where public transportation is usually an afterthought, Houstonians are often forced to rely on personal vehicles. At Rice University, the alternative form of transportation is a shuttle system provided by the university, which, in theory, should provide students with a convenient schedule. In practice however, the system has clogged the inner loop and provides students with an erratic schedule, as well as engine exhaust and traffic. Furthermore, an infrequent schedule curtails students’ ability to make routine shopping trips to places such as Target. As a result, students tend to rely on their personal vehicle, which is evidenced by the fact that out of an undergraduate student body of over 3000, “1,300 undergrads are registered to park on campus at this time” (Morgan 2009). The increase in personal vehicle use has led to an increase in parking lots on campus. These unsightly parking lots have taken up a considerable amount of space especially in the western part of campus where the Greenbriar visitors’ lot is located. The use of bikes as a mode of transportation would be an eco-friendly alternative that could potentially lower carbon emissions. There exists a myriad of successful bike share programs across universities in the United States and Canada. There are several different kinds of bike share programs that have been used. The anarchic program involves refurbishing recycled bikes for use by any of the students on campus1 (Davila, Jackson, Kim, Ricondo 2008). The co-op bike loan program entails loaning bikes to a certain group of people who may pay fees to keep the upkeep the program 2(Davila, Jackson, Kim, Ricondo 2008). The non-automated hub program involves checking out bikes from an attendant 3(Davila, Jackson, Kim, Ricondo 2008). The automated hub program involves using an ID to check out a bike from an automatic bike rack 4(Davila, Jackson, Kim, Ricondo 2008). As recommended by the previous year’s bike project group, the best way for a bike program to be established at Rice would be to start with a pilot program at the residential colleges (Davila, 1 This type of program been implemented at Hampshire College, University of Calgary, Davidson College, University of British Columbia 2 This type of program has been implemented at Middlebury College, University of Alberta, University of Ottawa, University of Toronto at Mississauga, University of Wyoming, and University of Toronto Scarborough 3 This type of program has been implemented at Emory University, Duke University, McGill University, University of Waterloo, Ohio State University, Rhodes College, Saint Michael’s College, University of Kentucky, University of Washington, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 4 This type of program has been used at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Jackson, Kim, Ricondo 2008). The present bike situation on campus at Rice is that there are too many bikes and not enough bike racks. After review of the data, we feel that Rice’s community would benefit greatly from a bike sharing network; now is the time to implement a residential college bike-share program. We hope that it will serve as a model that, in the future could be built upon, which will help improve students’ quality of life, as well as impact students’ overreliance on the campus shuttle and personal vehicle. Methods and Procedure We sought to create a working bike-share program that could be enacted with little to no overhead or initial capital. Furthermore, we sought to enact a program that reduced the need to procure additional resources. Not only would a low-cost version of the project appeal to university administrators and other staff we would be working with, but also, we saw it as an environmentally friendly alternative to purchasing a set of new, off-theshelf bikes. Besides implementing a pilot program, we sought to measure its effectiveness as well as its real environmental impact, excluding the factor of convenience. Thus we turned our attention to the sizeable collection of bikes that the Rice University Police Department had impounded. The group determined that procuring used, but refurbished, bikes from RUPD was aligned with our concept of a low-cost bike sharing program. Ideally, obtaining and performing a safety diagnostic of the bikes would be at no cost to us. Furthermore identifying an on-campus source for the bikes allowed us to incorporate a sense of sustainability in our project; that is, we were making full use of the resources presented to us by the university as well as contributing the university’s suitability commitment. Access to RUPD’s repository of bikes allowed us to meld our priorities of sustainability (and by extension, environmentally friendly development) and financial viability. After a discussion with Captain Hassell of RUPD, our bike liaison within the police department, we were able to establish an agreement which gave us unfettered use of bikes obtained from the department. We were also provided with our own bike rack to secure the bikes. Our first meeting was fruitful and yielded a number of positive developments: First and foremost, we received CAPT Hassell’s approval as well his encouragement and enthusiasm for project; however he did caveat the latter by informing us of a previous bike-share venture that had failed Secondly, CAPT Hassell was willing to provide us with safety related accessories for the bicycles; sold by RUPD at cost to them, we were provided with 5 Bell helmets to be used by participants in the program. Using this safety equipment, we were able to address the liability issues. CAPT Hassell also briefed us on RUPD bike regulations and how certain steps had to be taken by our group in order to ensure that we were in full compliance: All participants would be required to have a working knowledge of the Bike Policy; this issue was solved by providing a printed copy of the Bike Policy to all participants in the program. Secondly, all bikes would be required to display the RUPD bike registration decal We felt encouraged by CAPT Hassell’s assistance as well as his enthusiasm for the project. Following our meeting, we set up an appointment to consult with Renee Block, the university’s liability coordinator. She was our point of contact regarding the liability disclaimer that the group had presumed we would be required to present to all riders. After thoroughly discussing all the aspects of our proposed project, we received her consent and began to do the leg work involved in enacting the program; meanwhile, Ms. Block created a liability disclaimer for our use, which was provided to the project participants before using the bikes. Next, we created a survey to measure the effectiveness of the program, and allow us to determine its positive environmental impact. For this we used the survey collection tool provided by www.surveymonkey.com . We sent out an email message politely requesting program participants to fill out the survey; all questions within the survey were made mandatory to ensure a response for all questions. Within the survey, we asked questions to determine if students were using the bikes to forgo walking (convenience) or as an alternative to driving (environmental impact). Furthermore, we also intended to determine if students were willing to not buy their own bikes or not bring their cars to campus if the bike sharing program was expanded to provide full service to all of Rice University Students. Once all the results were collected, survey monkey allows one to analyze the data for free using its own built in data analyzer. We compiled the responses to the survey to get an idea of the effectiveness of the program, the feasibility of an expansion, as well as the environmental impact of the program. Finally, our project was implemented on Friday, November 6th 2009. Survey Results and Analysis Our results were measured via two surveys. The first survey (before-survey) was provided by the college coordinator at Will Rice/McMurtry for students who were checking out a bike to fill out prior to use of the bike. (see Appendix B.) This survey was designed to be very brief and consisted of four multiple choice questions about ownership of a car or bike on or off campus, what this service was being used in lieu of (taking the shuttle, walking, etc.), and planned destination(s). In addition the survey recorded the name, date, and contact information of the student and required them to sign their consent to be contacted later with a second more indepth evaluation survey. The second survey (after-survey) was created online in two parts using the website SurveyMonkey.com and was sent to students who had already checked out and returned a bike. (see Appendix C.) This survey consisted of both multiple choice and short-answer questions and was designed to evaluate the program in terms of environmental benefits (distance travelled, choosing this program over bringing a personal car or bike to campus, etc.) and convenience/enjoyment. We also asked students to give their opinions about a larger scale program in order to gauge the feasibility and recognize potential obstacles to future implementation. Besides the two surveys, we also had a “Check In/Check Out” sheet where students recorded the date, time, bike number, and condition of the upon checking out a bike and then again upon checking it back in. Also recorded were the students names and netIDs incase they needed to be contacted about returning a bike. From this information we were able to evaluate whether or not there was a trend in number of bikes checked out per day that could potentially correspond to popularity of the program. The following graphs represent the data collected from both surveys: The following tables contain direct quotations from the after-surveys: Strengths of the Program # of times mentioned “The fact that the students can rent bikes to do different activities is itself the programs main strength. I myself used the bike to go to Target, which was about 1.5 miles south of campus. I know a few people who have used the bikes to go to Academy and Taco Bell and other places. These bikes allow students to become mobile on their own and not rely on cars to go places.” 1 “You can check out a bike for free.” “I like that there is a fixed maximum time for which you rent the bike (24hours). This way, bikes can be rotated amongst college members.” “Convenience.” “It allows students another means of transportation for on- or off-campus travel.” 2 1 4 1 Weaknesses of the Program Solutions “Limited hours.” Possibility of a semester-long rental period in the future. (Would require more bikes though). A larger scale program would require more bikes which would make it easier to get bikes of more variety. “Need more variety of bikes (dirt for trails, low/high resistance, etc.).” “Not that many bikes” Expansion of program would require increasing the number of bikes in use. Bikes in the future would be chosen from RUPD by “Bikes’ quality is low.” college members to ensure quality. Also the bikes would be inspected and fixed by a paid employee of Bicycle World rather than an RUPD officer who is just doing it in his spare time. In the future there will be no need to fill out before“Inconvenient check-out process. If a student is in a hurry, they have to go through surveys since we will not be measuring anything. the entire sign out process before being given However the sign in/out process will have to continue until a better method (automated hub perhaps) is a key. Also, I don't know what students do to instituted in order to keep track of the bikes. check out a bike on weekends or after the College Coordinator's work hours.” “The bikes were too small for me The bikes were broken down. I had to fix both the handle bars and the seat post.” Additional response: “No weaknesses”. More variety of bikes could include more bikes of different sizes. Also if Rice were to engage in a retainer with Bicycle World, a bike maintenance expert would come to campus often to check up on the bikes and make repairs. Biggest Obstacles to this Program Being Solutions Implemented on a Wider Scale “The biggest obstacle to this program on a wider scale could be the misuse of the bikes and irresponsible handling of the bikes.” “Complication on larger scale, hours of operation.” “Off-campus safety (theft, assault, rules of the road, etc.)…” “Awareness.” “Costs of bike maintenance.” “The process of signing out a bike becomes more difficult, and also ensuring the bike's return at an appropriate time.” College owned program – college pride and sense of ownership of bikes Colleges have personal responsibility for bikes and have incentive to take care of them and use them properly. More bikes would facilitate more use. Also, there is the potential of creating an automated-hub system in the future where the bikes are checked out via ID card so bikes can be checked out and returned 24/7 rather than just during the college coordinators’ office hours. “…Perhaps a (short) education component to the program could address safe biking practices. Could be in the form of a presentation that must be attended previous to renting or a comprehensive flyer...” Perhaps a bike sharing info session during O-Week to explain the process and rules. If implemented at the college level everywhere, bike share program could be introduced during O-Week. Also seeing painted bikes around campus would increase awareness. There is the potential of creating an automated-hub system in the future where the bikes are checked out via ID card so bikes can be checked out and returned 24/7 rather than just during the college coordinators’ office hours. Analysis In total, 30 people were recorded as having checked out bikes during our trial period (November 6 to November 25). 25 people filled out the before-survey, 10 responded to part 1 of the after-survey, and only 7 responded to part 2. The number of bikes checked out per day was recorded from information gathered from the Check In/Check Out sheet (see Appendix A). We were hoping to see a positive trend in the number of check outs per day as people became more aware of the program. Our data, however, actually shows a decline in the number of check outs toward the end of our trial period. We attribute this primarily to fact that our trial period ended right before the Thanksgiving holiday so there were many end of the year exams and projects due that week and students were probably more focused on schoolwork and preparing for the break. We were overall pleasantly surprised by the number of students who used this program. Although the majority only used it once, about 10% of the people who checked out bikes checked them out three or more times which shows us that there were a number of people who enjoyed this program enough to use it multiple times. Since this program’s primary focus was to offer an alternate form of transportation for students, we were interested to find out how many of the students using our service owned their own bike or car. Although we found that the majority of students owned neither a car nor a bike on campus, we are hoping that in the future this program would discourage students from bringing their own cars and bikes to campus and hopefully reduce the amount of bike waste (broken down and abandoned bikes), overcrowding of bike racks, need for more parking lot space, and amount of CO₂ emitted by Rice students. Although 100% of respondents recorded having travelled less than a total of five miles during the period of their bike loan, a significant number recorded having taken the bikes to various off-campus destinations that are often travelled to by car or shuttle bus (for example: Target, Old Spanish Trail, someone’s home, etc.) The fact that a majority of students travelled off campus with the bikes displays the usefulness of the bikes in facilitating mobility and offering an alternate, zero-emissions means of transportation. This was further emphasized by the number responses that recorded intending to use one of our bikes instead of a private vehicle or the shuttle system. In addition, the people who responded that they would have forgone going to their desired destination at all if it weren’t for the bike service allows us to safely assume increased mobility was a desirable outcome of our project. The majority of students, however, considered convenience and quick access to their destinations to be the primary benefits of the program. We were not surprised by these results since we had originally tried to make the program as convenient as possible for students at Will Rice/McMurtry since convenience is often a driving factor in a student’s choice for transportation. In addition a number of students recognized that the program was beneficial in offering an alternate form of transportation besides driving or riding in a carbonemitting vehicle. Although this is a relatively small percentage, it shows us that there are a number of students who understand the environmental benefit of using bikes and would potentially continue to use them for that reason. Our previous conclusion about increased mobility was also supported by the 13% of students who responded that getting off campus was a primary benefit of the program. Implication for Future Implementation From an environmental standpoint, one of the main goals of our program was to offer an alternate means of transportation for students other than carbon-emitting vehicles like cars and buses. As a long term goal for the program, we hoped that it would eventually discourage students from bringing personal vehicles to campus. From our survey we gathered that although the majority of students would still bring a car to campus in the future, 40% responded that they would not. Currently at Rice there are about 1,300 undergrads are registered to park on campus (Morgan, 2009). If 40% were to forgo bringing a car in the future, it would decrease the amount of cars on campus by about 520, a number we can consider to be pretty significant. Also in the future we can assume that as the program grows in size and popularity, the number of students who take advantage of it will also grow. If we can create a “bike culture” on campus in the future it could ultimately cause an even more significant decrease in the number of cars brought to campus than what we estimate now based on our results. As far as facilitating a larger program on campus goes, we can look at some of our results from these surveys to determine the feasibility of implementing such a program and factors to consider if such a program were to be implemented. The majority of people responded as to having heard about the program primarily from Joyce Courtois, the Will Rice/McMurtry College Coordinator, although word-of-mouth among students at the college, flyers, and announcements at the Will Rice Diet meetings proved helpful as well. In the future if this project were to be implemented at additional colleges, more emphasis should be placed on advertisement of the program throughout the college and not just through the college coordinator. More posters, flyers, and listserv emails would help promote the program as well as maybe an informative meeting prior to the start of the program. However, the fact that there was communication about the program through word-of-mouth shows a level of excitement about and anticipation for the program that we can expect at other colleges as well. In general students appeared to like the program, as it received an average rating of 4.1 out of 5 (5 being the highest score possible) and an average rating of 4.4 out of 5 in terms of how it fulfilled students’ expectations. This was further emphasized in the fact that 100% of respondents would consider using the program again and would support its implementation on a wider scale, despite some obstacles pointed out by the respondents (see Table: “Biggest Problems to this Program Being Implemented on a Larger Scale”). We can determine that our project was ultimately successful in creating a somewhat sustainable program of recycled bike because students who responded to the survey unanimously asserted an interest in using the program again in the future. Recommendations Our group was surprised by the pace at which students began to use our pilot program at Will Rice and McMurtry. Furthermore, we gathered much more data than we had expected to. This unexpectedly large quantity of data allowed us to reach conclusions with greater certainty. Nonetheless, when examining the strength of our group’s program, the time allotted must be accounted for. We had one and a half months to design and enact a bike sharing program, collect data, compile this data into a report and judge the success of our pilot program. Thus time was our greatest motivator, but also greatly influenced the quality of our program. More time would have provided an even larger pool of data from which to draw conclusions and assess trends. Time also allows for adaptation; in our case, an increase in the number of bicycles available for use. Furthermore, our response to issues ranging from a broken chain to lost keys would have been less pressured. Issues such as these would have been given proper attention, rather than ignored by the group for the sake of time. Aesthetics would be elevated in priority. The time allotted for painting the bikes was greatly truncated due a slower than expected receipt of the bikes from RUPD. Most disappointingly, we were unable to invite Will Rice and McMurtry students to help paint the bikes simply because time was not on our side. Nonetheless, it must be noted that the end results gained from the pilot program exceeded expectations. Those delays that we did experience were the result of less than expedient responses from college presidents and members of the Rice staff with whom we were coordinating our efforts. In light of the considerable time constraint that accompanied the project, our group contends that the aforementioned recommendations would serve only to strengthen an already successful program. Beyond recommendations for future projects of this nature, ample discussion must be reserved for the continued implementation of the Will Rice and McMurtry Bike Share Program. We found that by maintaining the bike share program as a college-specific program, it increased the popularity of the program and made it more manageable. There is a collective feeling that the program is unique to one’s college and thus there is a feeling of college pride associated with the program. In addition, in order to allow uninhibited access to the bikes, the college coordinator mustn’t be the sole person with access to bike keys. A system involving swiping student ID cards would be ideal, but costly. Finally, make it free; college students are drawn to all things free of charge. More specifically, there are three areas which are vital to the continued success of the program and for the success of a campus wide program. These are: personnel, budgeting and mechanics. With regards to personnel, continued implementation cannot rely on the continued involvement of the four members of our group. A campus wide program must involve residential college-level and Student Association-level involvement. Much like the Eco-Rep program, there would be a member of the Student Association who would act as the coordinator for a campus-wide program. Not only would this individual keep the SA abreast of issues and events regarding a bike sharing program, but he or she would also be informed of budgeting issues. In turn, a Bike-rep would act as the college-level coordinator. This individual would be aware of any mechanical issues with the bikes or other minor issues such as missing parts. This information would then be passed along to the SA-level bike program coordinator who would keep a tally of all major issues. As with all student government positions, the incumbent would remain in the respective capacity for one academic year. The SA-level bike program coordinator would be selected, or elected, by the Student Association’s bike committee. The bike-rep would be a position open to all interested applicants. The final selectee could be appointed by the college president. The system ensures that undue burden is not shouldered by one individual. Budgeting would involve two pools of money. The college-level bike-rep would have purview over a smaller pool of money. This could be used for smaller expenses such as the purchase of spray paint to cover a scratch or give a bike a new paint job. This money would be part and parcel of the college’s budget. This money would have to be requested at the respective colleges’ government meetings. The SA-level bike coordinator would in turn have a budget allotted from which mechanic payments could be drawn, as well as more costly items such as helmets and bike locks. In order to ensure the continued safety of the bikes involved in the program, regular diagnostics as well as ad-hoc repairs would be needed. Unfortunately, the RUPD’s in-house bike mechanic would not be available due to other departmental commitments. However, Bicycle World, in Rice Village has voiced in an interest in acting as the sole provider of mechanics for a bike-share program on campus, no matter the cost. Were a bikesharing program to be implemented campus-wide, Bicycle World would paid a monthly, deeply discounted retainer. In turn, a mechanic would visit campus once a week to ensure that bikes are operating properly and conduct repairs as needed. The SA-level bike coordinator would liaise with Bicycle World on this issue and would provide the money for monthly retainer payments. The most important factor for success, be it for the Will Rice-McMurtry Bike Share Program, or for a campus-wide bike share program, is enthusiastic involvement. If there is a lukewarm response to the concept, or if an individual shirks his or her duties, then the program will not survive. Conclusion We sought to discover a way in which we could expose students to the positives of bike ridership while reducing their reliance on Rice University’s shuttle network and personal vehicles. Furthermore, we envisioned a bike-sharing program, no matter how large or small, as an opportunity for students to go beyond the hedges. While our group had visions of grandeur in the form of a gratis, campus-wide bike sharing program, we understood the importance of focusing our efforts on a college-level pilot bike share program. From this first step, we could assess the viability of a larger project. We were astounded by the success of the Will Rice-McMurtry Bike Share Program which we created. Not only were bikes being used, but students were using them to go beyond campus. A handful travelled as far as the Target Superstore on Main Street. This receptiveness was an encouraging confirmation of our initial hypothesis: Rice is ready for a bike share program and a program will receive a positive response amongst the student body. We were confronted with many issues to be sure, nonetheless it is our group’s belief that Rice is the perfect environment for a larger program. The question of the environmental impact of the program, or an imagined larger one, proves to be more elusive. Not only can we not confidently identify an amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide reduced because of our program – although, given the scale of the program, it is undoubtedly a small number – but we cannot state the reduction of cars as a result of a campus-wide bike share program. Through our analysis of the project, we have found that a bike share program of any size acts as an improvement for students’ quality of life. However, one must realize that a bike share program provides exposure to bike ridership for many who would never have had the opportunity. Thus there is a real potential for such a program to, over time, convince one, or many, to chose riding a bike over personal vehicle ownership. This may very well decrease the need for the dedication of so much land on campus to parking lots. While our Will Rice-McMurtry Bike Share Program may not have provided a measurable environmental impact, we feel that it was an overwhelming success. Furthermore, we have reached the conclusion that Rice University provides the ideal setting for a bike-share program; a program which would serve to greatly increase the quality of life of Rice students and decrease their reliance and fossil fuel burning transportation. Bibliography Bureau of Transportation Statistics. 2007. “BTS| Table 1-11: Number of U.S. Aircraft, Vehicles, Vessels, and Other Conveyances.” Retrieved November 27, 2009. (http://www.bts.gov/publications/national_transportation_statistics/html/table_01_11.html). Energy Information Administration. 2008. “World Energy-Related Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 1990, 2005, and 2030.” Retrieved November 26, 2009. (http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/1605/ggrpt/pdf/cde.pdf). Energy Information Administration. 2009a. “Greenhouse Gases- Energy Explained, Your Guide To Understanding Energy.” Retrieved November 26, 2009. (http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=environment_about_ghg). Energy Information Administration. 2009b. “Greenhouse Gases’ Effect on the Climate- Energy Explained, Your Guide to Understanding Energy.” Retrieved November 26, 2009. (http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=environment_how_ghg_affect_climate). EPA. 2009a. “Basic Information | Transportation and Climate | US EPA.” Retrieved November 26, 2009. (http://www.epa.gov/oms/climate/basicinfo.htm). EPA. 2009b. “Carbon Dioxide- Human-Related Sources and Sinks of Carbon Dioxide| Climate ChanceGreenhouse Gas Emissions| US EPA.” Retrieved November 26, 2009. (http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/emissions/co2_human.html). InflationData. 2009. “Inflation Adjusted Oil Price Chart.” Retrieved December 4, 2009. (http://www.inflationdata.com/inflation/images/charts/Oil/Inflation_Adj_Oil_Prices_Chart.htm) International Energy Agency. 2009a. “IEA Statistics CO2 Emissions From Fuel Combustion Sources Highlights 2009 Edition.” Retrieved November 26, 2009. (http://www.iea.org/co2highlights/CO2highlights.pdf). International Energy Agency. 2009b. “WORLD ENERGY OUTLOOK 2009 Fact Sheet. Why is our current energy pathway unsustainable?” Retrieved December 4, 2009. (http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/docs/weo2009/fact_sheets_WEO_2009.pdf). International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers. 2007. “OICA>> Climate Change and CO2.” Retrieved November 27, 2009. (http://oica.net/category/climate-change-and-co2/). Personal communication with Michael Morgan through E-mail, December 3, 2009. Puentes, Robert and Adie Tomer. 2008. “The Road… Less Traveled : An Analysis of Vehicle Miles Traveled Trends in the U.S.” Brookings. Retrieved November 27, 2009. (http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/reports/2008/1216_transportation_tomer_puentes/vehicle_miles_tr aveled_report.pdf). Texas Transportation Institute. 2007. “Table 2. What Congestion Means to Your Town, 2007 Urban Area Totals.” Retrieved November 27, 2009. (http://mobility.tamu.edu/ums/congestion_data/tables/national/table_2.pdf). World Resources Institute. 1999. “The global commons: Proceed with caution: Growth in the global motor fleet.” World Resources 1998-1999: Environmental change and human health. Retrieved November 27, 2009. (http://www.wri.org/publication/content/8467). OUT Appendix A. Name Bike # net ID Date Time IN Condition Initial Date Time Condition Initial Appendix B. Name Student ID Date Time Bike # Email Completion of the following brief survey is required before each use of this service. Please check any and all that apply: Do you own a car? On campus Off campus No Do you own a bike? On campus Off campus No You are using this service in lieu of: Private vehicle Own bike Walking Where are you planning to go on this bike? Around campus Medical Center Other (Please specify) Shuttle/metro Not going at all Surrounding Area (Rice Village) I ___________________________________ hereby give consent to release the above contact information to Bike Program coordinators and agree to participate in a follow-up survey and possible interview* in relation to the Bike Program. *details and links to an online survey will be emailed to participant following return of the bike (signature) Appendix C. After-Survey Part 1: < http://www.surveymonkey.com/s.aspx?sm=qcFIdrC59thkeRPbvoOLjQ_3d_3d> After-Survey Part 2: < http://www.surveymonkey.com/s.aspx?sm=qcFIdrC59thkeRPbvoOLjQ_3d_3d> Appendix D. Budgetary concern: All bicycle helps and “U”-bolt locks were sold, at cost, by Rice University Police Department to the CSES by way of an interdepartmental transfer The bike rack was from the university Housing and Dining department. $15.86 at the University Copy Center for posters advertising the program $71.34 at G&G Model Store for spray paint $139.15 at Bicycle World of West U for bike lights $110.97 at The Home Depot for painting supplies Our sincerest thanks to the teachers of the Environmental Issues course ENST 302 for guidance, the Rice University Police Department for providing the bikes and accessories, Ms Renee Block of the liability office and Will Rice and McMurtry Colleges for providing a testing ground for the pilot program. We have neither given, nor received any unauthorized aid on this assignment.