A Journey into the English Sentence

advertisement

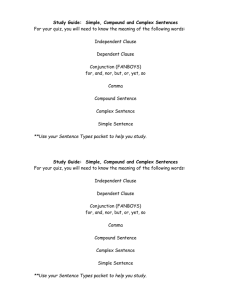

A journey into the English sentence by Sarah Williams “A subject thought: because he had a verb With several objects, that he ruled a sentence.” Stephen Spender; Subject, Object, Sentence (c) 2010 The UWIC Academic Skills Team START Our destination 1. The main clause 2. Dependent clauses 3. Concord 4. Compound sentences 5. Now break the rules Conclusion and resources Our destination This five-stage interactive lesson aims to give you a full understanding of the structure of correct sentences in standard, written British English. We demonstrate how the various sentence elements work, largely avoiding technical explanation. The longer first section teaches you the very basic definitions you do need. The lesson is progressive, with each part depending on the knowledge from the previous part. We recommend strongly that you work methodically from part to part, making a return visit if necessary. At the end, we hope you will feel you control the language, rather than feeling the language is always there to trap you. Carry-on luggage You need a pen and paper for some of the tasks. Where we have had to use an incorrect example, we show this with a * sign, the standard linguistic notation for syntax which does not follow rules. Most journeys are better undertaken with a friend. If you can find someone else interested in sentence construction, work through together so you can discuss the various tasks. The concluding resources section has a downloadable pdf version of the lesson slides, along with recommendations for further self-study. Timings are given on the separate sections. There’s a lot to absorb here, so if you feel overloaded, either take a break or return later. First, what do you know already … ? Spend two minutes jotting down what you think are the characteristics of a complete, correct, English sentence. Then hide your definition and proceed to the first section! 1: The main clause All simple sentences, or main clauses of compound sentences, must contain a subject and a verb. Most main clauses in sentences in formal written English will also contain an object. You will often see this pattern called SVO or “Subject-Verb-Object”. This section shows you how the SVO structure of main clauses works. Time needed for this section: 45 minutes to one hour. Subject – Verb – Object 1 Here are two very short, perfectly correct sentences. John skips. John skips class. On the next screen there’s a map showing the elements of both sentences. Before you look at the map, which parts of each sentence do you think are the subject, verb and object? Subject – Verb – Object 2: a map Subject Verb Object1 John skips class. The operator of the sentence. What the subject does. What is acted upon by the subject. Together, subject, verb and object form the main clause of a simple sentence. Some sentence types do not need objects. We discuss these on the next screen. 1 Some types of object are called ‘complement’ instead. These usually appear in sentences with the verb ‘to be’. For example, in “The car was red”, red is a complement. We overlook this difference here as is not critical to understanding sentence structure. We refer to both object and complement as ‘object’. Subject – Verb – Object 3 A sentence with only a subject and a verb (SV) can be perfectly correct e.g. “John skipped.” Here the verb is intransitive: this means the verb has no object and just describes what the subject does. SV sentences are rare in academic and formal writing. Sentences with a subject, verb and object (SVO) are much more usual in academic writing. Here the verb (“skips”) is transitive; it acts on, or affects, an object (“class”). Many English verbs can be both transitive and intransitive, often with an amusing change of meaning: “John stripped.” (intransitive) or “John stripped the wallpaper.” (transitive). The main clause – rule 1 A complete sentence in standard written English must have a main clause. The main clause must include at least a subject and a verb (SV). Usually it will contain a subject, verb and object (SVO). Now we’ll look more closely at the SVO elements. The main clause – the subject Look at the seven sentences in the SVO table below. Can you see what all the subjects have in common? Subject Verb Object The dog stole my homework. He My mother, my sister and I Eating my homework My carelessness Miss Bark A pack of dogs ate chased made was punished roamed it. him. the dog sick. my fault. me. the neighbourhood. The main clause – rule 2 The subject of a main clause must include at least one noun or noun substitute. Look at the table below for the different types. Subject Noun form Explanation The dog concrete noun A concrete noun is something you can see e.g. bridge, camel, desert. An article – “the”, “a”, or “an” usually precedes a concrete noun. He pronoun A pronoun substitutes for a noun already mentioned – here, “he” = the dog. Pronouns in objects can change form e.g. “I gave the book to her.” vs. “She gave it to me.” My mother, my sister and I concrete nouns and a pronoun in a list Subjects can have more than one noun, or mix pronouns and nouns. Eating my homework gerund or –’ing’ or activity noun Verbs in “-ing” forms can act as nouns e.g. “Running makes you fit.” My carelessness abstract noun An abstract noun is an idea, or concept. Miss Bark proper noun A proper noun is a named noun e.g. Mount Everest, Denmark, Nelson Mandela, a Norwegian. A pack of dogs compound noun Compound nouns, or noun phrases, comprising more than one word, are often linked by “of” e.g. Houses of Parliament. The main clause – rule 3 The main clause must include a verb. It doesn’t matter what tense or verb-type is used, provided it makes sense with the rest of the sentence. Verbs are easily identifiable as ‘action’ words, but tenses are often formed with other words around them. Look at the table before for some examples of different tenses. Example Verb Explanation The dog stole my homework. stole This is the one word verb (steal) in its past form. Miss Bark will give me a detention. will give Adding ‘will’ makes the future form of give. I must buy new school books. must buy A simple one word verb “buy” preceded by a modal verb “must” indicates obligation. I can’t get over my terrible maths result. can’t get over “Get over” is a phrasal, or multi-word, verb. Here it has the negative form of the modal verb “can” in front. This is very colloquial English and should not be used in essays; however, it is useful to be able to recognise verb structures in this form. The main clause: practice 1.0 On each of the next five pairs of slides, you will see a simple sentence on the A slide. Identify the subject, verb and object and then flip to the B slide to see if you were right. The main clause: practice 1.1 A Poor weather affected the success of the 2009 Summer Fayre. The main clause: practice 1.1 B Subject Verb Object Poor weather affected the success of the 2009 Summer Fayre. The main clause: practice 1.2 A We engaged in a gruelling autumn tour of the UK. The main clause: practice 1.2 B Subject Verb Object We engaged in a gruelling autumn tour of the UK. The main clause: practice 1.4 A The Higher Education Funding Council of Wales and the Welsh Assembly control most higher education finance in Wales. The main clause: practice 1.4 B Subject Verb The Higher Education Funding Council control of Wales and the Welsh Assembly Object most higher education finance in Wales. The main clause: practice 1.5 A The university will be looking for students to fill its new golf management course. The main clause: practice 1.5 B Subject Verb Object The university will be looking for students to fill its golf management course. The main clause: practice 2.0 On each of the next two pairs of slides, you will again see a simple sentence on the A slide. This time there is an element missing which prevents the sentence being complete. Identify the missing part, then flip to the troubleshooting B slide to see a solution and explanation. The main clause: practice 2.1 A The exhausting day to day grind of running a household, in addition to holding down a full time job. The main clause: practice 2.1 B Subject Verb The exhausting day to day grind of running a would defeat household, in addition to holding down a full time job Object most people. Trouble-shooting This sentence is only a subject: it lacks a verb and an object. When you have a very long subject, including a sub-clause and several “-ing” words (exhausting, running, holding etc.) which are not acting as verbs, it is easy to confuse one of these words for the main verb. The question to ask is “What happened in this sentence?” The main clause: practice 2.3 A Sailed into harbour as the tide went down. The main clause: practice 2.2 B Subject Verb Object The ship sailed into harbour as the tide went down. Trouble-shooting This sentence is only a verb and an object. Again, the writer may have been confused by the presence of the verb “went” in the “as” time phrase at the end. The question to ask is “What sailed into harbour?” While subjectless sentences are quite popular in contemporary literary writing, they have no place in academic writing and should be avoided. Summary of the main clause elements Main noun types concrete abstract proper pronoun activity nouns (gerunds) Verb types transitive intransitive Subject Object / Complement Examples: dog, biscuit, badminton carelessness, hunger, motivation Miss Bark, Harrogate, Denmark, Amanda it, she, he, they eating, running, singing, managing Explanation: Needs an object Does not need an object Must include a noun or pronoun Part of sentence acted upon by the main verb 1: Book cover tease You should now have no difficulty in identifying the subject, verb and object of the lurid book-title opposite! The next section looks at the differences between main and dependent clauses. 2: Dependent clauses This section looks at writing more elaborate sentences with dependent clauses, as well as the main clause. You will learn to tell the difference between the two clause types, and to ensure your sentence always has a main clause. Time needed for this section: about 25 minutes. Identifying a dependent clause 1 So far you’ve looked at relatively simple sentences containing just a main clause. The sentence below has three clauses, shown by the colours. Which one do you think is the main clause, and why? Turn to the next slide for an explanation. As the young singer was successful in his first professional performance, his manager booked a gruelling autumn tour of the UK, promoting what they hoped would become the 2009 Christmas number one. Identifying a dependent clause 1 Part Clause type and why As the young singer was successful in his first professional performance, Dependent clause1. Clauses giving conditions, or reasons, are common at the beginnings of sentences, and frequently start with the words “as”, “because”, “if” or “when”. If you want to change this clause type to a main clause, you need only remove the condition word e.g. “The young singer was successful in his first performance” is a perfectly acceptable sentence on its own. his manager booked a gruelling autumn tour of the UK, Main clause. This is indicated by the presence of a subject “his manager”, a main verb “booked” and object “a gruelling autumn tour of the UK”. promoting what they hoped would become the 2009 Christmas number one. Dependent clause. To convert this to a main clause you would need to add “They were promoting … “ 1 You’ll also see these called subordinate clauses by quite a few books. We prefer dependent because it reminds you that this type of clause cannot exist on its own. Dependent clauses: practice 1.0 On each of the next four pairs of slides, you will see a multi-clause sentence on the A slide. Identify just the main clause in each sentence, and then flip to the B slide to see if you were right. The B slide sentence will have the main clause highlighted in mauve. Dependent clauses: practice 1.1A Speaking as your manager, I am warning you that a continuation of this behaviour will not be tolerated. Dependent clauses: practice 1.1B Speaking as your manager, I am warning you that a continuation of this behaviour will not be tolerated. Dependent clauses: practice 1.2A When I was a child, I was incredibly shy. Dependent clauses: practice 1.2B When I was a child, I was incredibly shy. Dependent clauses: practice 1.3A When faced with a similar situation, participants will now know they have approximately 30 minutes to recover. Dependent clauses: practice 1.3B When faced with a similar situation, participants will now know they have approximately 30 minutes to recover. Dependent clauses: practice 1.4A Despite the hard work by the PTA committee, and the continued efforts of the fundraisers, bad weather affected the success of the 2009 Summer Fayre. Dependent clauses: practice 1.4B Despite the hard work by the PTA committee, and the continued efforts of the fundraisers, bad weather affected the success of the 2009 Summer Fayre. Dependent clauses: practice 2.0 Open up the exercise1 in your preferred version below. You will see 12 sentences. Decide if they are complete sentences with a main clause, or incomplete sentences. Try to correct the incomplete examples. If you are working in a pair, try reading the sentences to each other (part of the object of the exercise is to recognise aurally when sentences are incomplete or complete). Then check your answers using the button below. Word version 1 PDF version from Collinson, D, Kirkup, G, Kyd, R, and Slocombe, L (1992) Plain English Buckingham: OUP (pp-54-55). ANSWERS Trouble-shooting independent clauses Dependent and main clauses can appear in any position in a sentence. A sentence is not necessarily complete because it is long: it may just be a chain of dependent clauses with no main clause. Another sentence part often mistaken for the main clauses is a time phrase, especially when it contains a verb e.g. “By the time I had gone to sleep” is a dependent clause. Mistaking a dependent clause for a main clause often happens with ‘condition’ or ‘relative’ clauses starting with ‘”As”, “When”, “Which”, or “If”. “-ing” nouns such as ‘”speaking” can also be confused with main clause verbs. Careless writing from notes can lead to missing main clauses. Bullet points and lists are often composed of verbless statements and key words. As you write and edit, check every sentence has a main clause including subject and verb, and probably an object. 2: Book cover tease You should now have no difficulty in identifying the type of clause comprising the book title opposite! The next section looks at ‘concord’, or how you make the subject and main verb of your main clause agree. This is also known as ‘subject-verb agreement’. 3: Concord Concord means your subject and verb must agree in number: single subjects go with single verbs and plural subjects with plural verbs. The difficulty can lie in determining the plurality of a subject, especially if it is a long one. Time needed for this section: about 25 minutes. Concord – examples Look at the two sentences below. One is correct and one is incorrect: can you say why? The strength and ductility of a solid depends on how easily cracks will occur. The presence of such substances as carbon, silicon and sulphur affects the behaviour of cast iron. … if you are stuck, identify subjects, verbs and objects. Concord – explanation The first sentence is incorrect. It has a double subject connected by “and”. This makes the subject plural. Therefore the main verb – depend – must be plural too. The second sentence is correct. The main noun of the subject is “presence”. This makes a singular subject. Therefore the singular main verb – affects – is fine. The strength and ductility of a solid depend on how easily cracks will occur. The presence of such substances as carbon, silicon and sulphur affects the behaviour of cast iron. For a quick review of plural / singular verb differences, visit verb forms. Concord – more examples Here are four more examples with their main verbs highlighted. This time all the sentences are correct. Can you say why? A special feature of the wine series is the individual ratings given for quality, price and best recent vintages. The government has decided it will impose higher pension contributions on civil service workers. Gavin or Charlotte causes trouble at the pub every week. None of the rugby team plays golf in his spare time. Go to the next screen to find out if you were right. Concord – more explanation A special feature of the wine series is the individual ratings given for quality, price and best recent vintages. The main noun of the subject, “feature”, is singular. However, it is part of a noun phrase ending in a plural i.e. “series”. It is very easy to forget that this is a singular subject when a plural word is next to the verb. The government has decided it will Collective nouns such as “government”, “team”, impose higher pension contributions “department” can be interpreted as both singular on workers. entities and as groups of individuals. Just be consistent and make sure any subsequent pronouns are correct e.g. has + it, have + they. Gavin or Charlotte causes trouble at the pub every week. Placing “or” between two subjects makes them a single choice of two. Therefore the verb reverts to its singular form. You could also add “either” in front of this sentence. None of the rugby team plays golf in his spare time. None means literally “not one of”. Therefore it must be treated as singular. Another example is: “Neither Gavin nor Charlotte says they will get married. “ Concord: practice 1.0 Open the worksheet below in your preferred format. Read the nine sentences. Put a next to the sentence if its subject and verb agree properly. Put an if they don’t, and also provide a correction. You can access the key from the answers button. As before, if you are working in a pair, take it in turns to reading the sentences to each other to see if you can recognise subject-verb agreement aurally. Word version 1 PDF version Nos 1-5 and 7-9 from Collinson, D, Kirkup, G, Kyd, R, and Slocombe, L (1992) Plain English Buckingham: OUP (pp-59) ANSWERS Concord: the only rule! Subjects must agree in number with main verbs Singular subject = singular verb Plural subject = plural verb The only verbs affected are those in present tenses, and past tenses involving was and were. Where concord can tie itself in knots: 1 Plurality of a subject can be difficult to establish, especially if there is a complex, long subject including singular and plural nouns e.g. The limitation of exhaust emissions and atmospheric pollution generally by the application of smoke control regulations is a further step in the improvement of the road-user’s environment. Establish clearly the controlling noun of a subject: in the example above it is “limitation”, a singular noun. The main verb “is” occurs 15 words away from its controlling noun! Where concord can tie itself in knots: 2 Plurality can genuinely be ambiguous where singular nouns represent groups e.g. The government has decided it will raise taxes. The government have decided they will raise taxes. Both versions are acceptable; however, problems can arise with maintaining the appropriate pronoun reference. Stick to one version or the other during a piece of writing. Where concord can tie itself in knots: 3 “Neither/nor”, “either/or”, “no-one”, “nobody”, “none” (meaning “not one”) “each” and “every” are singular: Neither Dafydd nor Daniel was in the office. Every book is security-tagged. But none in the meaning of “nothing left” or “no-one left” can be singular or plural: There are none [=students] in the room. There is none [=beer] in the fridge. There are none [=beer bottles] in the fridge. Where concord can tie itself in knots: 4 Some regional dialect forms or ‘street English’ e.g. “*We was”, “*You was”, “*I were” ignore plural and singular verb differences, especially with “to be”. Some dialects also use plural pronouns in a singular meaning e.g. in Cumbrian, “We” and “us” are freely used to mean “I” and “me”. Certain plurals such as “pounds” are often reduced in dialects e.g. “*Twenty pound was paid.” Electronic grammar checkers are frequently unreliable and/or wrong: they have a poor ability to recognise more than the most basic sentence subjects. Train yourself to identify the main verb and controlling noun of the subject and you will become a far superior grammar checker!. 3: Book cover tease Fill in the gap in this sentence: “The flight of the conchords _____ cancelled.” 4: Compound sentences This section examines how to deal with compound sentences containing more than one SVO clause. You are shown how correctly to link compound sentences, avoiding common pitfalls such as comma splices. Time needed for this section: about 20 minutes. Understanding compound sentences Here are two sentences. See if you can identify the main clause in each of these sentences. Drivers should not panic or leave their vehicles, they should remain calm until help arrives. She wishes her son had not become involved with the group so early in his career, their negative influence undoubtedly led to his current incarceration. Now turn to the next screen for explanation. Explaining compound sentences Both sentences have two independent main clauses, each of which can stand alone as a sentence. Drivers should not panic or leave their vehicles. They should remain calm until help arrives. She wishes her son had not become involved with the group so early in his career. Their negative influence undoubtedly led to his current incarceration. Compound sentences are fine (and to be encouraged in formal writing) but they must be connected properly. Here are the sentences, now connected properly. Drivers should not panic or leave their vehicles; instead they should remain calm until help arrives. She wishes her son had not become involved with the group so early in his career because their negative influence undoubtedly led to his current incarceration. The next screen gives you the rules about compound sentences. Rules about compound sentences 1. A compound sentence has more than one independent clause obeying the subject-verb-object format. 2. The clauses are connected either with a co-ordinating conjunction, or punctuation with the function of a coordinating conjunction. 3. Commas cannot be used on their own to connect compound sentences: this creates “comma splices” or “run-on” sentences. If you were told at school that “commas divide sentences”, forget this ‘rule’ now because it is wrong! The next two screens will look at how coordinating conjunctions and punctuation work. As we are now going to get a little bit more technical, you are permitted a brief scream before continuing. Meet the FANBOYS 1. The little words on the right, known as coordinating conjunctions, are the most common way to link compound sentences. They often do not require additional punctuation. There are other conjunctions, but these are the most usual. 2. You’ve already met correlative conjunctions e.g. “either ... or “ and “neither ... Nor”. They behave like FANBOYS but act in pairs. 3. Do not use more than one co-ordinating conjunction per sentence! With rare exceptions, repeated conjunctions lead to sloppy writing. 4. Let’s see some FANBOYS in action on the waves of compound sentences on the next two screens ... for and nor but or yet so Co-ordinating conjunctions in action Clarke was surfing off the Cardiff barrage and but yet so when a shark ate him. Co-ordinating conjunctions in action The shark was pleased with its lunch for as because it hadn’t eaten since the previous weekend. Co-ordinating punctuation Now you’ve seen how to connect a compound sentence with conjunction words, let’s look at the two punctuation signs which do the same job; the colon and the semi-colon. Myths surround the use of colons and semi-colons. Before going on, reflect on what purposes they have, and what the differences are. Write a couple of examples for yourself including colons and semi-colons (there’s a big clue in the first paragraph above). Trouble-shooting fear and loathing of the ; A semi-colon connects two independent clauses where the second clause explains, or elaborates on, the first e.g. the example on the left in the cartoon. Semi-colons are often paired with qualifying adverbs such as “however” and “besides” if they are used in compound sentences e.g. Grade inflation is a growing problem in contemporary universities; however, upper second degrees remain a popular benchmark for employers. Trouble-shooting fear and loathing of the colon Colons act very similarly to semicolons. Use a colon where the second half of your compound sentence extends rather than explains the first half. Normally you do not need a qualifying adverb after a colon e.g. Grade inflation is a growing problem in contemporary universities: both employers and students are beginning to question the viability of more and more graduates with firsts and upper seconds. Compound sentences: practice 1.0 On each of the next five pairs of slides, you will see a sentence on the A slide. Decide if it is a compound sentence or not, then flip to the B slide to see if you were right. Compound sentences: practice 1.1 A If they had taken time to review the risk assessment before the trial started, the accident might have been avoided. Compound sentences: practice 1.1 B If they had taken time to review the risk assessment before the trial started, the accident might have been avoided. The first clause is a dependent clause starting with “If” (a condition) and the second clause is an independent clause. Compound sentences: practice 1.2 A While it was initially panned by the critics, The Shawshank Redemption has risen to the top of many people’s favourite films list: the stand-out performances of Freeman and Robbins, together with King’s powerful and compelling narrative, are doubtless the persuading factors. Compound sentences: practice 1.2 B While it was initially panned by the critics, The Shawshank Redemption has risen to the top of many people’s favourite films list: the stand-out performances of Freeman and Robbins, together with King’s powerful and compelling narrative, are doubtless the persuading factors. There are two independent clauses here. Note that the first clause is preceded by a dependent clause, and second clause is split by a sub-clause. Compound sentences: practice 1.3 A 49 athletes finished the marathon in three hours and a further 23 finished in four hours. Compound sentences: practice 1.4 B 49 athletes finished the marathon in three hours and a further 23 finished in four hours. There are two independent clauses connected by the conjunction ‘and’. This sentence is a good example of parallelism (repeated subject and main verb) and could be much more neatly written thus: 49 athletes finished the marathon in three hours and a further 23 in four. Compound sentences: practice 1.4 A The three top reasons most commonly given by employers for turning down graduates after interviews are: poor attention to personal hygiene, lack of interview preparation and written mistakes in applications. Compound sentences: practice 1.4 B The three top reasons most commonly given by employers for turning down graduates after interviews are: poor attention to personal hygiene, lack of interview preparation and written mistakes in applications. There is one main clause which does not end at the colon. What follows the colon is a list forming the object (or complement) of the sentence, not a second independent clause. Compound sentences: practice 1.5 A Three years after starting their gruelling six year course, medical students of all varieties normally exchange their formal university environment for clinical practice in the form of an internship at a large city teaching hospital. Compound sentences: practice 1.5 B Three years after starting their gruelling six year course, medical students of all varieties normally exchange their formal university environment for clinical practice in the form of an internship at a large city teaching hospital. There is only one independent main clause with the verb “exchange”. The opening clause is a time clause and is dependent on the main clause. Trouble-shooting compound sentences Mistakes in compound sentences can be avoided by: • Not relying on electronic grammar checkers. • Deciding clearly whether the sentence is compound or not at the outset (a lot of errors occur during hasty editing when sentences are not checked). • Being clear about the function of the interior punctuation in the sentence. • Understanding the role of ; and : signs. • Challenging the authority of poor advice from primary and secondary school e.g. “when in doubt, put in a comma”; “use commas to separate sentences”; “put some commas in to give it some air”; and “write as you speak” are all fail-safe recipes for run-on or ‘comma splice’ sentences. 4: Book cover tease Do you fancy editing this famous title in the light of what you now know about compound sentences? 5: Now break the rules … This section examines briefly the two main sentence types which do not conform to the standard subject-verbobject format in the main clause: passive and imperative constructions. Time needed for this section: 20 minutes. ... now break the rules Formal written English contains two sentence types which appear to omit subjects and do not follow the rules you have looked at so far. These are passive and imperative structures. Look at the two pairs of sentences on the next screen. What are the differences between each sentence in the pair? What are the subjects, verbs and objects? ... now break the rules Universal local authority maintenance grants for students were removed by the government nearly 20 years ago. The government removed universal local authority maintenance grants for students nearly 20 years ago. Cambridge University was founded in 1209. A renegade group of students from Oxford founded Cambridge University in 1209. Passive vs. active sentence forms The first sentence in each pair is a passive construction. The object comes first, followed by the verb with was, were or another form of to be in front of it. The subject may be changed into an “agent” preceded by the word by. Cambridge University was founded by a group of renegade students from Oxford in 1209. Passives are often a better choice of sentence when the subject is not known, or if it is simply irrelevant, or if it is not a conscious entity. Some examples are opposite. 131 books were stolen from the library last year. (=we don’t know the identity of the thieves) Cambridge University was founded in 1209. (=we are interested in the date, not the anonymous founding students) Bubonic plague is caused by a bacterium carried in the guts of infected fleas. The fleas in turn are carried by rats. (=we are interested in how bubonic plague is transmitted rather than the rats and fleas themselves!) ... now break all the rules again What do all the following sentences have in common? Check all the pages before submitting the form. Consider applying for an internship first. Do not mix hot oil and water. Neither panic nor leave your vehicle; instead, remain calm until help arrives. Write up to 150 words for each answer. Imperative sentence forms All the examples start with a positive or negative verb in the present tense and do not include a subject. These are commands, or ‘imperative’ sentences. They only appear in the present tense. Imperatives are unusual in formal writing but are vital for assembling lists of instructions or rules. They are very common in exam instructions and assignment briefs. Double imperatives can appear with “either”/”or” (+) or “neither”/”nor” (-). Increase the heat only when the crystals have melted. Leave the building by all available exits. Either answer one question from each part, or two questions each from parts A and B. Neither talk nor eat during the exam. Do not attempt to use the lifts during a fire alarm. Practice with passive and imperative forms Passive forms Imagine a fascinating historical sport has been discovered by archaeologists excavating a site in central Cardiff. Write a short news report on the facts of the find and some of the suppositions being made about the sport’s origins. Use passive sentences where needed. Give your imaginary sport a name and publish your report on Facebook. Who knows, you might get people writing in thinking your sport is for real. Imperatives Write a ten-point funny ‘good behaviour’ charter for learners in your course. Use imperative forms and try to bring in some negative and double imperatives too. Pin your charter to a UWIC noticeboard and see what happens to it. Trouble-shooting passives and imperatives Like compound sentences, passive and imperative structures are frequently the victims of misunderstanding and ignorance. “Passives are bad academic writing”. No they are not: it depends how they are used. If passive structures are used to avoid locating and checking facts and sources, then they are poor writing. If the source or fact is simply unknown or could be misleading (or of minimal interest) then passive forms are vital e.g. “The Earth was formed six billion years ago” (passive) is very different in meaning from “God formed the earth six billion years ago” (active). “Passives make writing boring”. Partly true. Strong verbs and lively, varied sentences bring all writing to life. Reporting on a process, such as a detailed scientific experiment, will require passives just to avoid repetition of the subject e.g. “The researchers did step 1 … the researchers did step 2.” Full circle: what do you know now? Get out the definition of sentence structure you wrote at the beginning. How would you add to or change that definition? Conclusion: baggage claim This section briefly describes resources for further practice on sentence construction, all available in UWIC libraries. There’s also a PDF version of the lesson you can download. Woods, G (2006) English Grammar for Dummies and English Grammar Workbook for Dummies Hoboken: Wiley Publishing Together, these are the best possible ‘training course’ for those wanting to learn to write perfect English without the burden of learning technical grammar. The workbook is packed with entertaining exercises with a full key and feedback. Chapters 1-6 of the main book and 1-4 of the workbook provide a comprehensive overhaul of sentence structure, including everything covered in this lesson. There are UK and US versions but do not worry about the differences: unlike UK/US spelling, grammar differences are minimal. UWIC libraries own the workbook as an e-book. Collinson, D, Kirkup, G, Kyd, R and Slocombe L (1995) Plain English Buckingham: OUP Evans, H (1972, 2000) Essential English for Journalists, Editors and Writers London: Pimlico This is a cheerful little book packed with practical exercises. There is a very good self-assessment quiz at the beginning. Buy your own copy and write in it! Follow the advice here and you will never make a mistake of grammar or style again. This is a reference rather than a practice book. Palmer, R (2002) Write in Style London: Routledge (e-book in UWIC libraries) Quirk, R and Greenbaum S (1997) A University Grammar of English Harlow: Longman Again, packed with practical (often funny) exercises, Palmer’s book is a comprehensive guide to editing perfect English copy. Excellent advice is also given on style issues such as concision. This book is not for the faint-hearted: if you have grasped the basic grammar terms, you can look up almost anything here to do with English syntax. We have some shelf copies in UWIC libraries and copies turn up occasionally second hand. This is a summary version of Quirk and Greenbaum’s longer work A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. Download a PDF version of A journey into the English sentence. Thankyous Amanda Bennett, Andrew Morgans, Charlotte Arundel, Rachel Wilson and Stuart Abbott cheerfully allowed themselves to be trapped into writing many of the example sentences. Then they agreed to be white mice for testing the material. What great colleagues you are! I hope your sentences are forever purrfect ... ... Sarah Williams