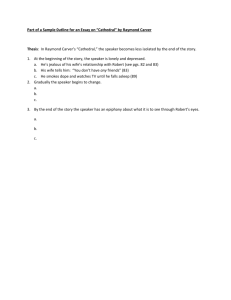

iii. “practical part”: analysis of the short stories

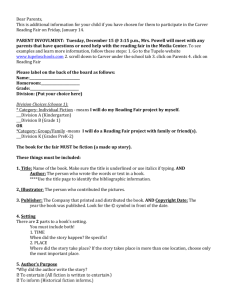

advertisement